In Japanese, a "counter," or josuushi 助数詞, is a word that comes after a number to say what sort of thing is being counted, e.g. "3 slices," mi-kire3切れ. More technically, it's a morpheme suffixed to a quantifier, which includes non-numbers like zen~ 全~, "all," and nan~ 何~, "how many."

- keeki wo mi-kire tabeta

ケーキを3切れ食べた

[I] ate three slices of cake. - banana wo san-bon tabete-iru

バナナを3本食べている

[I] have eaten three bananas. - nan-nichi ga kakaru?

何日がかかる

How many days will [it] take? - suu-byou de owatta

数秒で終わった

[It] ended in a few seconds. - {suu-kiro mo aru} ton'neru

数キロもあるトンネル

A tunnel [with] {many kilometers [of length]}.

Grammar

Basic Usage

Counters are the suffixes that go after numbers in Japanese. They don't actually have a lot of grammar rules that are specifically about them, most of the time, something that works with a word featuring a counter will also work with a similar word that doesn't have a counter.

For example, take the following sentences:

- asoko ni san-biki no sakana ga iru

あそこに三匹の魚がいる

There are three fishes over there. - asoko ni sakana ga san-biki iru

あそこに魚が三匹いる

Over there, of fishes, there are three. (literally.)

As you can see, there are two ways to say the same thing in Japanese. In the first sentence, san-biki, "three," is a no-adjective qualifying sakana, "fish." The phrase san-biki no sakana means "three fishes" by itself. The other way occurs when the number modifies the predicate, in this case, iru, instead of a marked noun.

Note that above sakana is marked as subject, marked by ga が, but it also works when it's the object, marked by wo を:

- san-biki no sakana wo tsutta

三匹の魚を釣った

[He] fished three fishes. - sakana wo san-biki tsutta

魚を三匹釣った

Of fishes, [he] fished three.

In any of these sentences, it's possible to replace the number-plus-counter san-biki by the word takusan 沢山, "many"," lots."

- takusan no sakana (ga iru/wo tsutta)

たくさんの魚(がいる/を釣った)

(There are/he fished) lots of fishes. - sakana (ga takusan iru/wo takusan tsutta)

魚(がたくさんいる/をたくさん釣った)

So as you can see, it's clear that this grammar isn't "counter" grammar, it's grammar about words that count stuff, which includes counters. Regardless, some notes anyway.

Sentence-Final Counter

Sometimes you have an incomplete sentence where a counted noun is marked as subject, and you have a counter/counting-word after the subject-marking particle, but no predicate. In this case, it most likely just means how many of the noun are there. For example:

- teki ga hitori

敵が一人

[There is] one enemy.

Of enemies, [there is] one.- An equivalent for the predicate for "there is" wasn't uttered in the Japanese phrase.

- mokuteki wa hitotsu

目的は一つ

[There is] one goal.

We have only one goal.

~te-iru Form

When counters are used with the ~te-iru ~ている form, the sentence may translate to "has done something N times" or "is doing something N times."

- hon wo san-satsu yonde-iru

本を三冊読んでいる

[I] have read three books.

[I] am reading three books.

The reason why this happens is due to what the ~te-iru phrase derives from.

First, observe the phrase below:

- {ko-inu wo korosu you na} hito da

子犬を殺すような人だ

[He] is a person [the sort that] {kills puppies}.

He's the sort of person that would kill a puppy.

Above, the phrase ko-inu wo korosu, "kills puppies," is a habitual predicate. Ignore the term "habitual," that's just how it's called in linguistics.

Anyway, a habitual predicate, sometimes called a dispositional, describes a situation that may happen under some situation, i.e. it has the disposition to happen. The way it works is complicated to explain.

In summary, we're saying that's the sort of person that would kill a puppy, instead of the sort that would never. So the situation "he kills a puppy" MAY occur, even if it hasn't occurred yet, or will never actually occur.

When the ~te-iru form is used, the hypothetical scenario where that "would" or "might" happen becomes existential. This is also known as the experiential ~te-iru because he will "have" in present tense the experience of having done the act.

- kare wa ko-inu wo koroshite-iru

彼は子犬を殺している

He has killed a puppy.- His disposition to heinous acts has been realized.

How do counters enter this scenario? Simply:

- {ko-inu wo ni-hiki mo korosu you na} hito da

子犬を二匹も殺すような人だ

[He] is the sort of person that would kill [not one, but] TWO puppies. - ko-inu wo ni-hiki mo koroshite-iru

子犬を二匹も殺している

[He] HAS killed [not one, but] TWO puppies.- That bastard!

As you can see, this is nothing special of counters, the grammar works the same way without counters.

It just happens that a counter plus ~te-iru with this experiential meaning stands out and confuses people learning Japanese, because it tends to occur in places where you'd expect the past tense instead.

- keeki wo han-bun mo tabete-iru

ケーキを半分も食べている

[He] has eaten half of the cake. (that bastard!)- Normally you'd expect something like:

- [He] ate half of the cake already!

The other way occurs in a situation where we have the progressive aspect applied to a whole habitual predicate. For example:

- mai-shuu hon wo ni-satsu yomu

毎週本を二冊読む

Read two books every week.

The above is a frequentative habitual. It expresses a thing that occurs at the frequency of every week. If we apply ~te-iru to this, we get:

- mai-shuu hon wo ni-satsu yonde-iru

毎週本を二冊読んでいる

[I] have been reading two books every week [lately].

The reason this works is because, in a way to analyze sentences, a habitual predicate of an eventive verb is considered stative. When a stative verbs is conjugated to ~te-iru, it means the state has been true for a certain while. For example, with potential verbs you can say:

- yuurei to kaiwa dekiru

幽霊と会話できる

[I] can talk to ghosts. (generally.)- kaiwa - suru-verb.

- yuurei to kaiwa dekite-iru

幽霊と会話できている

[I] have been able to talk with ghosts [lately]. (I wasn't being able to do it generally, but recently my ghost-talking powers have returned, so I can talk with them now. Not sure if this will last, though.)

Changes in Pronunciation

Counters are suffixes, as such, they're subject to changes in pronunciation that affect suffixes in Japanese at the morpheme boundary (shandhi), such as rendaku 連濁, sokuonbin 促音便, and handakuonka 半濁音化.

For example, the counter hatsu 発, for "shots" or "hits," is pronounced ~patsu ~発 when affected by handakuonka.

- ha は becomes pa ぱ.

- ichi hatsu becomes ippatsu

一発

One hit.

One shot.- Note: Japanese term for an "one shot" manga is yomi-kiri 読み切り, "read completely," instead.

These changes depend on the first consonant of the suffix. For a suffix that starts with the h~ consonant, there will be many variations depending on what the prefix ends with, e.g. hon 本 is pronounced pon or bon depending on what morpheme precedes it:

| Number | Prefix | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | ni に |

ni-hon にほん |

| 1 | ichi いち |

ippon いっぽん |

| 8 | hachi はち |

happon はっぽん |

| 6 | roku ろく |

roppon ろっぽん |

| 100 | hyaku ひゃく |

hyappon ひゃっぽん |

| 3 | san さん |

sanbon さんぼん |

| 1000 | sen せん |

senbon せんぼん |

| ? | nan なん |

nanbon なんぼん |

As you can see above, with prefixes that end in ~chi and ~ku, ~hon becomes ~pon, while the ~chi or ~ku becomes a small tsu っ; with suffixes that end in ~n, ~hon becomes ~bon instead.

This article won't include all possible variations, but it's important to keep in mind that the same counter can be pronounced different from how it's spelled in the dictionary because suffixing different numbers result in different pronunciations.

By the way, nihon 日本, "Japan," is pronounced with different accent than ni-hon 二本, "two cylindrical objects."

Static Pronunciation

Some counters do not change in pronunciation in cases where a typical morpheme would be affected by one. That is, the rules for these changes are different for counters than they are for typical multi-morpheme nouns.

For example, in many multi-morpheme nouns, if you have an ~n-k~ morpheme boundary, the suffix suffers rendaku and you get ~n-g~ instead.

- kin

金

Gold. - chingin

賃金

Wages.- Expected: chin-kin.

- kata

型

Shape. Model. Form. - shingata

新型

New model. New form.- Expected: shin-kata.

However, this change doesn't occur with these counters:

- nan-kire

何切れ

How many slices.- Expected: nangire.

- san-kai

三回

Three times.- Expected: sangai.

Counters vs. English Nouns

In some cases, like kire 切れ, "slice," a Japanese counter will translate to an English noun, however, that's not necessarily always the case.

In English, numbers to count nouns come before nouns, but in Japanese they come before counters, which aren't exactly the same thing as the nouns being counted.

For example, sometimes you have a noun that ALSO works as a counter.

- kono shurui

この種類

This type. This kind.- Here, shurui is a noun, since it's qualified by the prenominal pro-adjective kono.

- ni-shurui

2種類

Two types. Two kinds.- Here, shurui is a counter.

Other times, however, a counter can't be used as a noun.

- *kono mai

この枚

Intended: "this sheet."

(wrong: mai isn't a noun.) - konoha ni-mai

木の葉二枚

Two tree-leaves.

Above, our noun is a "leaf" ha 葉, of a "tree," ki 木. Normally we'd say ki no ha 木の葉, but in the case of the word "tree leaf" specifically it's pronounced irregularly, as konoha instead.

We're saying of this "leaf" thing we have "two," but to count this "two" in Japanese we use the mai 枚 counter, which counts sheet-like things, because a leaf is flat like a sheet. This mai can't be used like a noun with kono, and doesn't even translate to anything in English.

Homography

There are cases where a counter and a noun share the same kanji 漢字 and meaning, but are pronounced differently (i.e. they have different morphology), so they are different things that just happen to be written with the same kanji.

- kono katana

この刀

This sword.- Here, katana 刀 is a noun.

- san-tou-ryuu

三刀流

Three-sword style.- Here, tou 刀 is a counter.

Polysemy

In rare cases, you might have a word that's both a noun and a counter, pronounced and spelled identically, but whose meaning as a noun has nothing to do with its meaning as a counter. Notably:

- hon

本

A book. (noun.) - ~hon

~本

A long, cylindrical thing. (counter.)

Observe the difference:

- hon ni-satsu

本2冊

Two books.- satsu is the counter for books.

- ude ni-hon

腕2本

Two arms.- Arms are long, cylindrical things.

- Context: Shanks sacrifices his arm to save Luffy. (this is literally the first chapter.)

- ude ga!!!

腕が!!!

[Your] arm [is gone]!!! - yasui mon da

ude no ippon kurai...

安いもんだ

腕の一本くらい・・・

- ude no ippon kurai wa yasui mono da

腕の一本くらいは安いものだ

Around one arm is cheap.

In the sense of: just one arm is a small price to pay to save your life.

- mono da, contracted to mon da, is used at the end of sentences when explaining things.

- ude no ippon kurai wa yasui mono da

- buji de yokatta

無事でよかった

That [you] are unharmed was a good [outcome.]

[I'm glad you aren't hurt.] - .........u...

............!!

uu.........!!

・・・・・・・・・う・・・

・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・!!

うう・・・・・・・・・!!

*sobbing piratically*

Same Thing, Different Counter

As you may have realized already, Japanese counters are awkward because they don't refer to the thing themselves, they instead refer to an aspect of the thing, like of it as a sheet, or as a long and cylindrical object.

As such, it's entirely possible for the exact same thing to be counted with a different counter, depending on which aspect of that thing is most relevant, important, salient, etc. in a given context. This counter may vary according to:

- Why are we counting this? What we'll use these things for?

- How does the speaker feel toward the thing they're counting?

- How does society expect the thing to be counted?

A popular example is a fish. Depending on what it's going to be used for, you could say:

- sakana ippiki

魚一匹

One fish.- In this case, hiki 匹 counts to the fish as a small animal, e.g. in a river, or aquarium.

- sakana hito-kire

魚一切れ

One fish slice.- Okay, in this case the fish is being treated as a food, not as a live animal any longer. I mean, technically not a "food," but as a mass of flesh that can be sliced in pieces, doesn't matter if you're going to use those slices as food or not.

- sakana ichi-mai

魚一枚

One fish slice.- Wait a second, what's the difference between the above?

- With ~mai, the slice must be sheet-shaped. It must be thinly sliced, like a sheet of paper, like a leaf, etc. With kire, you can have a thick slice of the fish, a "piece" of the fish sliced off, just like you could have a thick slice of cake.

- Note that kire 切れ is the noun form of the verb kiru 切る, "to cut."

- sakana hito-pakku

魚1パック

One pack of fish.- Here we'd be referring to fish as a packaged good. One pack with several fish pieces.

That's not all. In the case of the tuna, maguro マグロ, that's a rather large fish, so it can be sliced in several different sizes depending on who is going to consume it, each form getting a different counter. That is, the words ichi-mai and hito-kire are used when it's a shape you can pick a slice with chopsticks to eat. Before that:(ものを数えるときには - sakai.ed.jp)

- ippon

一本

One cylindrical object.- This is used to refer to caught fish, fish being displayed because of their tube-like shape, specially if the fins are removed.

- icchou

一丁

One "serving." One "block."- The term san-mai oroshi 三枚おろし refers to cutting a fish in three parts: the head with bones, and the body in two halves without bones. The term icchou refers to one of the boneless halves.

- hito-fushi

一節

One "piece."- This refers to either half of an icchou sliced in half: either the belly or back part.

- hito-koro

一塊

One "lump."- When cut in blocks by cutting along the body. That is, if you start with a whole fish, remove the head, and split it into four parts like plus sign (+), each quarter is a chou's, and each chou is rather long, since they're as long as the fish originally was. Now you cut slices across the length, splitting it into shorter more block-like blocks that are counted with koro.

- hito-saku

一冊

One "slab."- After slicing the fish into koro's, the koro is slice into smaller slab-like slices, which can be packaged, for example.

- ikkan

一貫

One piece of sushi 寿司, e.g. fish on rice.

Counting People

When counting people, which counter is used is influenced by usual Japanese honorific shenanigans and by mixture of fantasy racism and/or idealism: after all, are they PEOPLE?

Let's start with something based on reality first. The normal counter for people is ~nin ~人, homograph with hito 人, "person." Exceptionally, for 1 person and 2 people, ~ri ~人 is used instead. So you end up with:

- hitori

一人

One person. - futari

二人

Two people. - san'nin

三人

Three people.

And the rest is regular, ending with ~nin. Although there are exceptions for that exception, like the word ichi-nin-mae 一人前, meaning an "adult" in the sense of you can handle yourself without a guardian or mentor.

- Context: Nozaki played a dating sim, in which the player's best friend, Tomoda 友田, kept helping the player in his romantic conquests in various ways, with hints, and free movie tickets. Moved by this, Nozaki decides to spend the night drawing a fan comic featuring Tomoda with a romantic partner, arriving to the conclusion he's more interested in the player than in any of the girls. In the next day, a finished comic is found by another character.

- manga...

マンガ・・・

A comic... - juuni-nin no bishoujo yori mo omae ga suki nanda!!

12人の美少女よりもお前が好きなんだ!!

[I] like you more than the twelve bishoujo!!- Each "beautiful girl" you can conquest in a dating sim is a bishoujo.

- The number 12 is written horizontally here. This is acceptable in Japanese and there isn't anything special about it.

- Tomoda!!!

友田!!! - sonna...!!!

そんな・・・!!! - ore wa... mi-mamotteru dake de... yokatta noni...

俺は・・・見守っるだけで・・・良かったのに・・・

I'd be [happy] with just watching over [you]... - poro...

ポロ・・・

*tear falling*

The honorific variant of ~nin is ~mei ~名. This kanji is also found in na 名, "name." So in certain formal situations, where there is a need for ceremony or other formalities, people will be counted with ~mei, not ~nin.

- ano ni-mei

あの二名

Those two people.

This isn't the only case of there being a honorific variant for a person word. For example, anata-tachi あなた達, "you (plural)," may similarly become anata-gata あなた方, and no hito-tachi の人達, "the people of [somewhere]" may become no kata-gata の方々 in formal social contexts.

Lastly, when referring to people not as people but as corpses, i.e. the number of bodies, then the counter ~tai ~体 may be used, which is homograph with karada 体, "body." This counter isn't limited to corpses, it can be used to count other human-shaped bodies, like dolls, androids, or giant robots.

Same Thing, Different Perspective

In some cases, which counter is used to count something depends not on what the thing is, what it will be used for, how it's shaped, or any other intrinsic attribute of the thing, but merely the values of the speaker counting the thing. From their perspective, that's how it should be counted.

A common example in manga are giant monsters counting tiny human beings not with any of the counters for "person," but with the counter for "small animal" instead.

The same principle occurs in series with slave traders who capture monster girls and demi-human races: they may refer to the slaves as animals instead of as people.

A series with anthropomorphic kemono ケモノ characters may have them counting themselves with ~hiki instead of ~nin, not unlike how in My Little Pony words like somepony, anypony, everypony are used instead of somebody, anybody, and everybody.

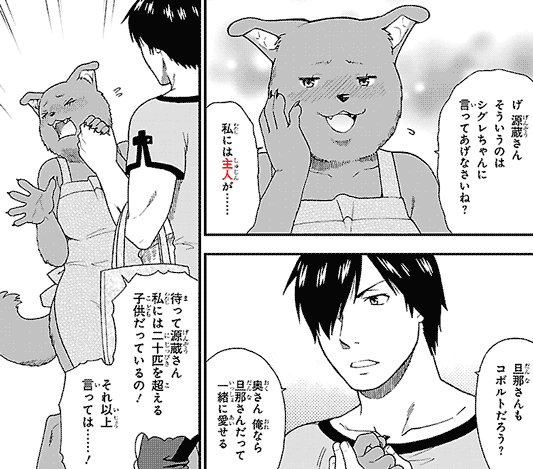

- Context: a furry flirts with a furry character.

- Ge, Genzou-san, souiu no wa Shigure-chan ni itte-agenasai ne?

げ 源蔵さん そういうのはシグレちゃんに言ってあげなさいね?

Ge, Genzou-san, that sort of thing [you should] say tell Shigure-chan, okay? (as in flirt with her, not me.)- itte-agenasai - nasai form of itte-ageru 言ってあげる.

- watashi ni wa shujin ga......

私には主人が・・・・・・

I [have] a husband......

- watashi ni wa {shujin ga iru}

私には主人がいる

{A husband exists} is true for me.

I have a husband.

- watashi ni wa {shujin ga iru}

- See also: plewds.

- danna-san mo koboruto darou?

旦那さんもコボルトだろう?

[Your] husband is a kobold, too, [isn't he]?- A kobold is a fantasy creature, which happens to be a furry character in this series.

- oku-san, ore nara danna-san datte {issho ni} aiseru

奥さん 俺なら旦那さんだって一緒に愛せる

[Lady], if [it]'s me, [I] can love [your] husband as well.- oku-san - used as title to refer to a "wife."

- aiseru - potential form of irregular verb aisuru 愛する, "to love."

- matte Genzou-san

まって源蔵さん

Wait, Genzou-san. - watashi ni wa {nijippiki wo koeru} kodomo datte iru no!

私には二十匹を超える子供だっているの!

I also have {more than twenty} children!- nijippiki - ni-juu 二十, "twenty," plus hiki 匹.

- sore ijou itte wa......!

それ以上言っては・・・・・・!

If [you] say more than that......!

- sore ijou itte wa dame

それ以上行ってはだめ

If [you] say more than that it wouldn't be good.

[You] shouldn't say more than that.

- sore ijou itte wa dame

Robots or monsters, who would typically be counted with ~tai, to be counted with ~nin by a character who treats them as a person, implying either than the character treats robots as people, or that the monsters were originally people who turned into monsters, or anything such.

With human experiments, where a live person may be counted as a body, with ~tai, if some mad scientists thinks of them as nothing but specimens to be used.

Although huge monsters may be counted with ~tai by humans, it's possible that there's an even huger giant who counts those exact same monsters as small animals with ~hiki. It's also possible for this speaker to not even be a giant in height, and be human-sized, but simply be so powerful that the monster is no different from a small animal for them.

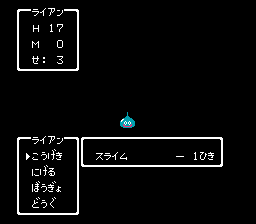

- Context: a battle screen showing what you're righting against:

- suraimu, ippiki

スライム、1ひき

Slime, 1.- Note: because it's an old game, it didn't have the capability of displaying kanji, nor the capability of changing the spelling of hiki when a change of pronunciation occurs, thus, it's spelled hiki ひき despite the pronunciation being ippiki いっぴき.

- Aian アイアン

(character name.) - kougeki 攻撃

Attack. (this doesn't work sometimes.) - nigeru 逃げる

Escape. (this never works.) - bougyo 防御

Defend. (who uses this lol.) - dougu 道具

Tool. (items, also known as yakusou 薬草, "healing herbs." Practically useless after you get a healer in your nakama.)

In any of these cases, the counter isn't just a detail like the exact number. Using an unusual counter may raise eyebrows, and even a tsukkomi. The counter is used to characterize the character through speech. It's a deliberate choice by the author which the audience will certainly pick and comment on across the internet even if the characters themselves don't say anything about it.

What Comes Before the Counter

What comes before a counter in Japanese is a quantifier. These include standalone number words (ichi, ni, san 一二三, etc.), some numerical prefixes that don't work as standalone words (hito~ 一~, futa~ 二~, etc.), the interrogative prefix nan~ 何~, and certain prefix that translate to "few," "some," "all," like suu~ 数~, "a number of," and zen~ 全~. A quick example with the counter for anime episodes, wa 話:

- nan-wa

何話

How many episodes?- As usual, an interrogative like this can be used with a ka か particle and mo も particle to produce sentences such as:

- nan-wa ka wakaranai

何話か分からない

[I] don't know how many. - {nan-wa mite-mo} omoshiroi

何話見ても面白い

[It] remains entertaining {no matter how many episodes [I] watch}.

- ichi-wa

一話

One episode. (in quantity, like two episodes.)- To say "episode one," an ordinal, you would say something like:

- ichi-wa-me

一話目

The first episode. (of any sequence, e.g. of the episodes I watched today, the first one was...) - dai-ichi-wa

第一話

Episode one. (used with canonical sequences, e.g. of the episodes of this series, the first one is...)

- suu-wa

数話

"A number of" episodes.

Several episodes.

Few episodes.

Many episodes.- suu-wa shika mitenai

数話しか見てない

[I] haven't seen more than a number of episodes.

[I] have only seen a few episodes.

- suu-wa shika mitenai

- zen-wa

全話

All episodes.

For zero, there are two words: zero ゼロ and rei 零. For measurements, zero ゼロ is normally used, but in some cases rei 零 is more common. Also, you're more likely to encounter "not even one" for things that are countable, rather than measurements.

- zero-en

ゼロ円 (or 0円)

Zero yen. (money, price.)- en 円 - counter for yen..

- rei-ten

零点 (or 0点)

Zero points. (on a score, exam, test, etc.)- ten 点 - counter for points.

- hon wo issatsu mo yondenai

本を一冊も読んでない

[He] hasn't read even one book.- satsu 冊 - counter for books.

Naturally, non-integer numbers and, really, negative numbers may be used with counters as well:

- itten-go-kiro

一点五キロ

One point five kilos.- kiro キロ - counter for kilograms, kilometers.

- mainasu ni-juu-do

マイナス20度

Minus 20 degrees.

20 degrees negative.

-20°.

- do 度 - counter for degrees.

- Note: for arithmetic, hiku 引く, "pull [out of]" means "minus," while tasu 足す, "add to (like salt to soup)" means "add," e.g. go hiku ichi 5引く1 means "5, then you pull out of it (i.e. subtract) 1," which translates to "5 minus 1."

Sometimes, a counter or quantifier turns the phrase into a fraction, for example:

- ichi-wari

1割

One tenth. 10%. - ichi-paasento

1㌫ (or 1%)

One percent.- ore wa mada ichi-paasento no chikara sura dashitenai zo

俺はまだ1㌫の力すら出してないぞ

I haven't even used one percent of [my] power.

- ore wa mada ichi-paasento no chikara sura dashitenai zo

- ichi-bu

一部

One part of.

One fraction of.- ichi-bu no ningen ni shika tokenai

一部の人間にしか解けない

No more than one fraction of humans can solve [it].

Only X% of all people can solve this!!!

- ichi-bu no ningen ni shika tokenai

- san-bun no ichi

3分の1

One of three parts. 33.3~%. One in each three of something. - han-nichi

半日

Half a day.- han 半 - quantifier for "half," which in practice, just like English, often doesn't really mean "exactly 50% of," but instead "this thing has two parts, and this is one of the two parts of it, half of it."

Pronunciation of the Number

Generally speaking, when counting things you use the ichi, ni, san words (the on'yomi 音読み of the number kanji 漢字), not hito~ prefixes (which would be kun'yomi 訓読み). There are some exceptions, however, specially with words that are normally used with the numbers 1 or 2. For example:

- hitori de yaru

一人でやる

[I] will do [i]t with one person. (literally.)

[I] will do [it] alone.

[I] will do [it] myself. (without another person helping me.)- ri 人 - counter for people.

- futari-kiri

二人きり

Two people exactly. (literally.)

The two of them became alone.

It was just them two.- kiri 切り - suffix for "exactly," specially when the count stops there, e.g. kore kiri これきり, "just this" in the sense of "my favor to you will be just this, and I will do nothing more, don't even bother asking."

- hito-kuchi

一口

[Give me] one bite [of that food].- kuchi 口 - counter for bites, mouthfuls.

There are cases of words that are pronounced with either kun'yomi or on'yomi numbers.

For example, it seems ~kire ~切れ is traditionally counted up until number four with kun'yomi, but it there's a modern trend of counting those with on'yomi instead. So some people say mi-kire 三切れ while others say san-kire 三切れ.(nyakomeshi:一切れ、三切れ、何と読みますか?)

| Word | kun | on |

|---|---|---|

| 一切れ | hito-kire ひときれ |

ichi-kire いちきれ |

| 二切れ | futa-kire ふたきれ |

ni-kire にきれ |

| 三切れ | mi-kire みきれ |

san-kire さんきれ |

| 四切れ | yo-kire よきれ |

yon-kire よんきれ |

| 五切れ | go-kire ごきれ |

|

"The Number Of"

When the kanji for "number," kazu 数, is suffixed to a counter morpheme, it's read ~suu but refers to the number of a countable thing. For example:

- nin-suu

人数

The number of people.

In this case, the counter morpheme nin doesn't actually work as counter grammatically, since there's no quantifier coming before it. You could use ~suu like this with any counter word, but in practice it seems more common to use the word kazu 数 with a noun being counted, for example:

- sakana no kazu

魚の数

The number of fish.

How many fishes. - sakana no hiki-suu

魚の匹数 - nanbiki no sakana?

何匹の魚?

How many fishes? - sakana no nanbiki

魚の何匹

An unknown number of fishes.

Fishes, I don't how many.

References

- 4月22日(水) ものを数えるときには・・・ - sakai.ed.jp, accessed 2023-05-30.

- 一切れ、三切れ、何と読みますか?たくあん一切れ、三切れは縁起が悪い? - nyakomeshi.com, accessed 2023-07-06.

No comments: