So you know nothing about Japanese and you want to know what a sentence in Japanese says. Well, this article is for you. For starters, the basic structure of a simple, typical Japanese sentence looks like this:

For example:

- {{sugoku(adv.)} sugoi(adj.)} hito(n.) wa(p.)

sugoi(adj.) na(p.)

すごくすごい人はすごいな

People(n.) [that] {are {incredibly(adv.)} incredible(adj.)} are incredible(adj.). (literally.)

An {{incredibly} incredible} person is incredible. - yo(n.) no(p.) naka(n.) niwa(p.)

{ii(adj.)} hito(n.) mo(p.)

{warui(adj.)} hito(n.) mo(p.)

iru(v.) yo ne(p.)

世の中にはいい人も悪い人もいるよね

In the world(n.), there are(v.) {good(adj.)} people(n.) and {bad(adj.)} people(n.), too, aren't there? - jibun(n.) wo(p.) shinjiru(v.) na(.p),

ore(n.) wo(p.) shinjiro(v.)!

{omae(n.) wo(p.) shinjiru(v.)}

ore(n.) wo(p.) shinjiro(v.)!!

自分を信じるな、俺を信じろ!

おまえを信じる、俺を信じろ!!

Don't believe(v.) in yourself(n.), believe(v.) in me(n.)!

Believe(v.) in the me(n.) [that] {believes(v.) in you(n.)}!! - shinjiraremasen(v.)

信じられません

[I] can't believe(v.) [it].

As you can see above, you often have a "n. p. n. p." noun-particle pattern, and v.'s tend to come after p.'s.

Some sentences have different structures, and we still don't know what adverbs, adjectives, verbs, nouns, and particles look like exactly. In this article we'll see all of this and some more, so you'll have a starting point even if you know nothing about Japanese.

Then, once you figured out the structure of the sentence, all that's left is to look up the words of the sentence in a dictionary (e.g. jisho.org), and with luck you'll understand what it means.

Note: this article is only about grammar. It's recommended you familiarize yourself with the Japanese "alphabets" before continuing.

Translating Inexplicitness

The first thing we must learn about Japanese grammar is that there are several ways in which sentences can be ambiguous, which means the English translation of a Japanese sentence will make some assumptions about what the sentence may mean.

For text you see translated elsewhere, e.g. in subtitles for an anime, the translator may have made the wrong assumption, so the translation ends up being wrong. In the case of the example sentences in this article, some words that are ambiguous or don't have a Japanese equivalent are put into brackets [like this], which means that same Japanese can have a different meaning in a different context.

Japanese sentences typically don't feature personal pronouns despite the English language requiring them. That is, although watashi 私 means "I," a sentence talking about "I" typically won't feature watashi (or other first person pronoun, such as ore 俺 or boku 僕).

- watashi wa nemui

私は眠い

I am sleepy. (explicitly.) - nemui

眠い

[I] am sleepy. (implicitly.)

If this same sentence was used with interrogative tone (asking a question), we'd likely interpret a second person pronoun instead:

- nemui?

眠い?

Am [I] sleepy? (it's unlikely I'm asking about myself.)

Are [you] sleepy? (likely I'm asking about whom I'm talking with instead.)

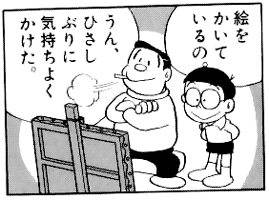

- e wo kaite-iru no.

絵をかいているの。

Are [you] drawing a picture? - un, hisashiburi ni {kimochi-yoku} kaketa

うん、久しぶりに気持ちよくかけた

Yes, for the first time in a while [I] was able to draw {feeling good}.- i.e. for the first time in a while, he was able to enjoy himself drawing.

- kaketa - past form of the potential verb of kaku 描く, "to draw."

This ambiguity exists for all personal pronouns: "I," "he," "she," "it." Including the plurals: "we," "they." And possessives: my, your, his, her, our, their, its.

- Tarou wa shukudai wo wasureta

太郎は宿題を忘れた

Tarou forgot the homework. (could be anyone's homework that he was supposed to bring.)

Tarou forgot [his] homework.

It's also possible for it to be a generic pronoun, translating to "one/one's" or "you/your."

- ha wo migaku

歯を磨く

To brush the teeth. (as in from your creepy teeth collection.)

To brush [one's] teeth. (as in those in your own mouth.)

A pronoun like "he" has two uses called deictic and anaphoric.

A deictic pronoun means the thing or person it refers to may change when the same sentence is spoken in a different context. For example, if Mary says "I'm here," then that means "Mary is here," but if John says it, that means "John is here," so "I" is deictic, referring to a different person depending on who utters it.

An anaphoric pronoun refers to a thing or person mentioned previously. For example: "John and his friends" means "John and John's friends." The pronoun "his" refers to "John" which is uttered before the word "his."

Most of the time an anaphoric pronoun is used in English there won't be an equivalent word in Japanese. For example:

- Tarou wa "akiramenai" to itta

太郎は「諦めない」と言った

Tarou said "[I] won't give up." (literally, direct quotation translation.)

Tarou said he wouldn't give up. (indirect quotation translation.)- Here, "he" in the indirect quotation is an anaphoric pronoun, as it refers to Tarou.

In these cases where there should be a noun or pronoun but there isn't, and the lack of such word works like a pronoun, it's said that there is a null pronoun. The term "null" in linguistics is used in these cases where not uttering anything has an unique meaning (this isn't the only null we'll encounter).

- φ - the Greek letter phi is sometimes used through this article to represent a null in analysis.

Alternatively, the concept of omitting pronouns is known as "pronoun dropping," so Japanese, which allows it in contrast to English, would be called a pro-drop language (which has absolutely nothing to do with monster drops, loot, or gacha, I swear).

Japanese has some expressions that indicate "respect" in a sense. This "respect" is always used toward others, not toward yourself, so a respectful word, too, is unlikely to be related to first person.

- o-namae

お名前

[Your/his/her] name.- o~ is a respectful marker, so a respectful namae wouldn't be of the speaker's.

- anata no o-namae

あなたのお名前

Your (respectful) name. - watashi no namae

私の名前

My name. - Similarly: kazoku 家族, "family," go-kazoku ご家族, "[your/their] family."

Some auxiliaries may also affect the pronoun translation:

- oshiete-ageru

教えてあげる

[I] will teach [you/him/her].- Generally, ~ageru is used when the speaker is doing something for someone else.

- oshiete-kureru

教えてくれる

[You/he/she] will teach [me].- Conversely, ~kureru is used when someone else is doing something for the speaker. Although exceptions exist.

In Japanese, there are no articles (a, an, the), thus a noun is ambiguous between definite and indefinite.

- neko wo hirotta

猫を拾った

[He] picked up a cat.

[He] picked up the cat.

In Japanese, there's generally nothing in a sentence to indicate if a noun is supposed to be plural or not, so they're also ambiguous in this sense.

- neko wa kawaii

猫は可愛い

A cat is cute.

Cats are cute.

The cat is cute.

The cats are cute.

Some reduplications like yamayama 山々, "mountains," hibi 日々, "days," and so on are plural (c.f. yama 山, "mountain," hi 日, "day"), but these are merely words that exist like this; you can't just take any word and say it twice to make it plural, e.g. *nekoneko doesn't mean "cats."

There are also pluralizing suffixes like ~tachi ~達 which are used to pluralize groups of people, e.g. kanojo-tachi 彼女たち, "she and the others," i.e. "them." Note that yuusha-tachi 勇者達 means either "the heroes" in the sense of every person that is a yuusha, or "the hero and the others" in the sense that there's one yuusha you're referring to and you're also referring to the other people with him (i.e. the hero and his party).

In these ambiguous cases, you'll need to rely on context to figure out which one of these is the proper way to interpret a sentence.

Postpositions

Japanese is a backwards language. Not only is text traditionally read right-to-left, wholly opposite to how English is read, but, also, it features postpositions where English would have prepositions.

A preposition in English is like the word "from." It's a PREposition because it comes BEFORE the word it affects: "from where," "from the start," "from Japan"—all these phrases start with the word "from" because it's the word after "from" that matters.

Meanwhile, in Japanese, the POSTposition kara から would be the equivalent, which comes AFTER the word it affects: doko kara どこから, hajime kara 初めから, nihon kara 日本から—all these phrases end with kara から because it's the word before it that matters.

Some examples:

- {isekai kara kita} yuusha

異世界から来た勇者

The hero [that] {came from another world}.- isekai 異世界 - "a different world," from where the hero came.

- ku-ji kara go-ji made

9時から5時まで

From nine-hours until five-hours. (i.e. from 9AM to 5PM.) - Tarou no kuruma

太郎の車

The car of Tarou.

Tarou's car.

Such Japanese postpositions are called "particles," joshi 助詞. They're generally only one or two syllables long, and are always written in hiragana, and by always I mean most of the time.

Consequently, if you see something written in hiragana after a word, there's a good chance that's a particle.

Particles have all sorts of functions and some of them don't have an English word equivalent, such as marking the subject and object, and topic and focus.

In English, the subject and object of a verb are determined through word order, for example:

- The cat ate the bird.

Above we have the verb "ate," which describes an action. This action has roles for two nouns: the subject doing the eating and the object being eaten. And we have two nouns: "the cat" and "the bird."

How do we know which noun is doing the eating and which noun is being eaten in English? Word order. The cat comes before the verb, so it's the subject. The bird comes after the verb, so it's the object. The cat eats the bird.

Since word order defines the roles of the nouns, changing the order of the words changes the meaning of the sentence because the role of the nouns change.

- The bird ate the cat.

- Well, well, well, how the turn tables.

Meanwhile, Japanese uses the particles ga が and wo を to mark the subject and object. In this context, "marking" means giving the noun a role.

- neko ga tori wo kutta

猫が鳥を食った

The cat ate the bird.- neko ga - the subject marked by the subject marker ga が.

- tori wo - the object marked by the object marker wo を.

- kutta - the predicate.

It's a bit weird that there's no translation for ga and wo, because this would translate to the order of the words in English.

Technical resources may spell out that they mark the nominative case and accusative case, respectively, along with meaning of other morphemes, so you may end up seeing someone write something like this eventually:

- neko-ga tori-wo kut-ta

Cat-NOM bird-ACC eat-PAST.Note: nom stands for "nominative," not for nom nom nom nom nom.

In Japanese, it's possible to change the order of the words without fundamentally altering the meaning of the sentence because it's the particles that give the roles. There is a standard word order, though, so variations such as putting the object before the subject tend to have some nuance.

- tori wo neko ga kutta

鳥を猫が食った

The bird, the cat ate.

- neko ga - still the subject because it's still marked by ga.

There are some particles that may come after other particles, in which case their meanings combine somehow. But do note that not every particle can come after any other particle (e.g. wo can't be marked by ga). Observe:

- nezumi wo mo kutta

ネズミをも食った

[The cat] ate the rat, too.- Here, mo marks nezumi wo.

- go-ji made wa modoranai

5時までは帰らない

[I] won't be back by five.- Here, wa marks go-ji made.

For reference, a list of particles found mid-sentence to have an idea of how they look like. This is a rough summary and doesn't include all the functions of every particle. Furthermore, beware some particles are homonyms with stuff that aren't particles, e.g. sometimes a ni に is the ni に particle, other times it's the ni に copula, and if you don't know there's a difference you may end up thinking ni に is always a particle, when sometimes it's not.

| Particle | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| wa* は | Topic. | sora wa aoi 空は青い The sky is blue. |

| ga が | Subject. Focus. |

{sora ga akai} sekai 空が赤い世界 A world [in which] {the sky is red}. |

| wo* を | Direct object. Medium. |

{keeki wo tabeta} hito ケーキを食べた人 The person [that] {ate the cake}. |

| ni に | Indirect object. Destination. |

{kita ni mukau} ressha 北に向かう列車 A train [that] {heads toward north}. |

| e* へ | Direction. | mirai e 未来へ Toward the future. |

| de で | Location. Instrument. Limitation. (plus others.) |

ohashi de taberu お箸で食べる To eat with chopsticks. |

| to と | Accompaniment. Exclusive "and." Quoting. (plus others.) |

tomodachi to taberu 友達と食べる To eat with [one's] friends. |

| ya や | Nonexclusive "and." | neko ya inu 猫や犬 Cats, dogs, etc. |

| mo も | Inclusion. | kako e mo ikeru 過去へも行ける Can go to the past, too. |

| dano だの | Citation "and." | samui dano atsui dano 寒いだの暑いだの [You complain] it's cold, it's hot. |

| tte って | Topic. Quotation. |

chikyuu tte nani? 地球ってなに? What is "Earth"? |

| ka か | "Or." | neko ka inu ka wakaranai 猫か犬かわからない [I] don't know if [it] is a dog or a cat. |

| shi し | Rationale. | tooi shi, ikitakunai 遠いし、行きたくない Because [it] is far, [I] don't want to go. |

| ~i ~い | Softens speech. | hontou ka i? 本当かい? Is that really true? |

The particles wa は and e へ are pronounced different from how they're spelled (spelled as ha and he, pronounced like wa わ and e え). And the wo を particle is pronounced o お.

Sometimes, a word appears to have a role that would be given by a particle—such as topic, subject, or object—but no such particle is found after the word.

When this happens, it's said that a null particle marks the word. As mentioned previously, in linguistics, "null" (represented by φ) means that the lack of something can be interpreted as having some meaning.

That is, the lack of a particle works like a particle, because that makes more sense than fundamentally changing our understanding of how Japanese works. Sometimes, this missing particle is even pronounced as a pause, which may get written as a space. Some examples:

- ore φ, Tarou

俺 太郎

I'm Tarou.- Same as ore WA Tarou.

- nani φ shite-iru?

何している?

What are [you] doing?- Same as nani WO shite-iru.

Note: there may be cases where the null particle isn't interchangeable with another particle, so it might not be correct to say that in every case a particle was omitted.

- Context: a bald man is being nice.

- banana φ yaru

バナナやる

[I'll] give [you] a banana.- Same as banana wo yaru.

- n? aa

ん?ああ

Hmm? Alright. - arigatou

ありがとう

Thanks.

Do keep in mind that there are other types of "nulls" in Japanese (and in English), so a φ isn't necessarily always a particle in this article.

A particle may be contracted or spelled in katakana, which occurs when a character speaks in unusual manner.

- ore a Tarou

俺ぁ太郎

I'm Tarou. - watashi wa robotto desu

ワタシハロボットデス

I'm a robot.

There are certain contexts where particle may get spelled with kanji, as a symbol, or even omitted from spelling. This mainly occurs in titles and names of things for aesthetic reasons, as writing it with hiragana may not look good enough.

- Kami no Tou

神之塔

Tower of God.- In the title of this series, the possessive no の particle is spelled as 之, which would be a possessive marker in Chinese.

- Tarou-san e, Hanako yori

太郎賛江、花子与利

To Tarou-san, from Hanako.- Found in postage. A real try-hard way to spell everything in kanji. See ateji 当て字.

- Oni-ga-shima

鬼ヶ島

Oni's Island.- oni 鬼 - a type of demon-like supernatural being from Japanese folklore.

- The possessive ga が is spelled as a small ke ヶ symbol in names of places, and names of people that come from names of places.

Some particles are grammatical case-markers and always come directly after nouns, and by always I mean sometimes they do not. For example:

- {furuku} kara aru

古くからある

[It] exists since {old [times]}.- furuku - this is an adverb.

- {katsu} ni kimatte-iru!

勝つに決まっている

[It] has been decided that {[he] will win}. (literally.)

It's obvious he's going to win!

There's no way he would lose!- katsu - this is a verb.

- {horobiru} ga ii

滅びるがいい

{Perishing} is good. (literally.)

[You] may perish. [You] shall perish.

Perish.- horobiru - this is a verb.

- See ~suru ga ii ~するがいい.

Sentence Structure Overview

Every Japanese sentence (or main clause) can be divided into three parts: sentence-ending particles, that go at the end of the sentence, the predicate, which goes before those particles, and other stuff (other constituents) that go before the predicate. Observe:

| Other constituents | Predicate | Particles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (none.) | atsui! 暑い! is hot! |

(none.) | |

| [It] is hot! | |||

| sekai ga 世界が World. |

owaru! 終わる! ends. will end. |

(none.) | |

| The world will end! The world is going to end! |

|||

| anata wa あなたは You |

dare desu だれです are who |

ka? か? (question)? |

|

| Who are you? | |||

| kare φ, 彼、 He |

tabako φ タバコ tobacco |

suwanai 吸わない doesn't suck won't suck |

yo よ (alert) |

| He doesn't "suck tobacco." (literally.) He doesn't smoke. |

|||

As you can see above, some sentences don't have sentence-ending particles, and some predicates don't come with other constituents, but if two or all three of these things are part of a sentence, they'll always come in this order, and by always I mean most of the time.

There are two exceptions.

Sometimes, one thing that should go before the predicate (i.e. in the left side) ends up after what would be the end of the sentence (i.e. at the right side). This is called a right-dislocation, because a constituent is dislocated (moved) to the right.

| Left side | Clause end | Right side |

|---|---|---|

| kore wa これは This |

nani φ? 何? is what? |

(empty.) |

| What is this? | ||

| (empty.) | nani φ 何 is what |

kore? これ? this? |

The other exception are doubling constructions, in which a constituent is repeated (doubled) at the end of the sentence. This sounds pretty weird in English sometimes.

| Left side | Clause end | Right side |

|---|---|---|

| are wa あれは That |

neko da yo 猫だよ is cat |

neko 猫 cat. |

| That is a cat, a cat. | ||

Except for these exceptions, from what we know so far, Japanese sentences follow a pretty regular pattern of: noun, particle, noun, particle, noun particle, this repeats a random number of times, predicate, and then sentence-ending particles.

And although some sentences don't have the stuff before the predicate, or after the predicate, they always have a predicate, and by always I do technically mean always this time, because every sentence has at least one clause and every clause has a predicate, every sentence must have at least one predicate, however, sometimes the predicate technically exists but is omitted.

Some unusual incomplete sentences omit the end of the sentence, so the sentence may end up ending in a mid-sentence particle. This occurs because the ending can be inferred pragmatically, that is, because it's obvious what comes after the mid-sentence particle. For example:

- Kono Subarashii Sekai ni Shukufuku wo φ!

この素晴らしい世界に祝福を!

[Give] Blessings to This Wonderful World!- Here the wo を particle marks the object and the ni に particle marks the destination or recipient, so it has to be a verb of sending something to someone or somewhere, which one can reasonably assume is "give" in this case.

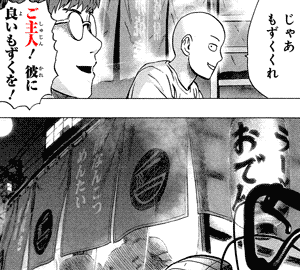

- Context: Mumen Rider, 無免ライダー, wants to thank some bald character by buying him some food.

- jaa mozuku φ kure

じゃあもずくくれ

Then, give [me] mozuku.- mozuku - a type of edible seaweed.

- kure - imperative form of kureru くれる.

- goshujin! kare ni yoi mozuku wo φ!

ご主人!彼に良いもずくを!

Owner! [Give] him [some] good mozuku!

In English, auxiliary verbs like "did" require a Verb Phrase complement to come after them, but in some cases there is no such VP. This is called VP-deletion, or null complement anaphora. In Japanese, a similar thing occurs with predicates, except there are no auxiliaries like in English, so they're omitted entirely from a sentence and their absence is interpreted anaphorically. For example:

- Context: someone announces bad news, a listener reacts.

- ou ga shinda!

王が死んだ!

The king died!- Here, shinda is the predicate.

- ou ga φ?!

王が?!

The king [did] φ?!

The king [died]?!

- Here, the predicate is also shinda, but it's omitted.

- "The king did" is a VP-deletion of "the king did die?"

Conjunctions

In Japanese, conjunctions may come after a clause rather than before it, the opposite of English. Well, in any case the conjunction is in the middle of the sentence, so it doesn't really matter much, but punctuation like commas would appear after the conjunction, not before.

- sagashimashita ga, mitsukaranatta

探しましたが、見つからなかった

[I] searched for [it], but [it] wasn't found [by me]. (literally.)

Above, ga が, "but," comes before the comma in Japanese, but after the comma in English. The same applies to kedo けど and no ni のに, also meaning "but," "however," "thought," and no de ので and kara から, meaning "because," "so," "since."

Japanese sometimes features a conjunction at sentence ending position with the rest of the meaning omitted. Generally this occurs when asking for permission about something, or when unsure about the use of an information asked.

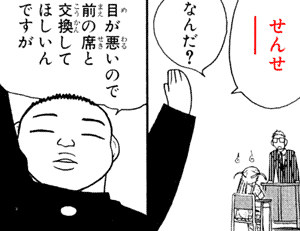

- sensee

せんせー

Teacher. - nanda?

なんだ?

What is it? - {me ga warui} no de mae no seki to koukan shite hoshii-n-desu ga

目が悪いので前の席と交換してほしいんですが

{[I have poor eyesight]} so [I] want to switch [with one of] the front seats.- me ga warui

目が悪い

Eyes are bad. (literally.)

To have poor eyesight.

- me ga warui

Above, the student ends his sentence with ga が. One can only imagine that despite wanting something, they can't get it by themselves: I want to switch, but [I need your permission]. The fact that they're asking the teacher to do something about it is implied and left unsaid.

It's also possible for the conjunction and its clause to be dislocated.

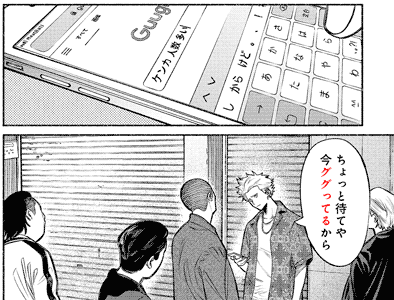

- Context: Masa 雅 finds himself surrounded, pulls out his smartphone.

- kenka, ninsuu, ooi

ケンカ 人数 多い

Fight, number-of-people, many. - chotto mate ya, ima gugutteru kara

ちょっと待てや 今ググってるから

Wait a bit, because [I] am googling right now.- Same as:

- ima gugutteru kara chotto mate ya

今ググってるからちょっと待てや

[I] am googling right now, so wait a bit.

There are also some conjunctions that appear at the start of a sentence, like shikashi しかし, "however."

Sentence-Ending Particles

Some sentences feature sentence-ending particles, which are particles that always go at the end of a sentence, and by always I mean most of the time.

They mainly exist in dialogue, in interlocutory contexts, where they're used by the speaker to convey what they feel about their statement or a situation, or express what they expect from the listener from hearing the statement. They aren't used in articles that just describe things objectively, for example, nor in narrations, signs, etc., that don't try to appear as if it were talking directly to the audience.

For example, yo よ can be used to warn the listener about something when the speaker thinks they don't know about it.

- moete-iru

燃えている

[It] is burning.- A mere statement.

- moete-iru yo

燃えているよ

[It] is burning.- A warning. An alert. Look, it's burning! Pay attention! Don't you realize this? Watch out!

Meanwhile ne ね is used to seek agreement sometimes, like saying "right?" or "isn't it?"

- moete-iru ne

燃えているね

[It] is burning.- *wink wink*

There are very few situations where these particles provide some information that's not already available from context. You can literally picture two characters saying something is burning, and, most likely, the one with yo よ will have a worried face, and the one with ne ね will have a smug face.

For reference, a list of sentence-ending particles:

| Particle | Function | Example |

| ka か | Question. | {Danjon ni Deai wo Motomeru} no wa Machigatte-iru Darou ka ダンジョンに出会いを求めるのは間違っているだろうか Is [it] Wrong {to Seek Encounters in a Dungeon}? |

| wa わ | Assertion. Incredulity. |

nai wa! 無いわ! [That] doesn't happen! (literally.) [No way]! [That can't be]! [You must be kidding me]! |

| yo よ | Urging. Alert. |

{sonna koto shitara} abunai yo そんなことしたら危ないよ {If [you] did something like that} [that] would be dangerous. |

| sa さ | Clarification. Reassurance. |

wakaru sa わかるさ [I] understand. |

| na な | Opinion. Agreement. |

dasai na ダサいな [Damn], [that] is lame. |

| ne ね | Confirmation. Agreement. |

dasai ne ダサいね [It] is lame, [isn't it]? |

| ze ぜ | Assertion. Proposal. |

issho ni nomou ze 一緒に飲もうぜ Let's drink together! |

| zo ぞ | Assertion. Alert. |

hyaku-nen mae no hanashi da zo 百年前の話だぞ [That] is a story from a hundred years ago. [That happened] a hundred years ago. |

Sentence-ending particles come at the end of the main clause, but they come before dislocated or doubled constituents, which means those are awkwardly "outside" the main clause. Even more awkwardly, sometimes a mid-sentence particle gets dislocated together with what it marks, so it ends up looking like it's a sentence-ending particle when it's not. For example:

- sosoru ze, kore wa!

唆るぜこれは!

- kore wa sosoru ze

これは唆るぜ

This excites [me]. - In the sense of to excite, to stimulate, to stir up, one's curiosity, interest, or other feeling.

- kore wa kyoumi wo sosoru

これは興味を唆る

This excites [my] interest.

- kore wa sosoru ze

Predicates

The thing at the very end of a simple sentence in Japanese is called the predicate. The predicate is a verb word or verb phrase, or an adjective or noun followed by a copula, which in practice works just like a verb anyways. Some examples:

- sora wa aoi

空は青い

The sky is blue.- "Is" - English copula.

- ~i - Japanese copulative suffix.

- neko wa doubutsu desu

猫は動物です

Cats are animals.- "Are" - English copula.

- desu - Japanese polite copula.

- maou ga fukkatsu suru

魔王が復活する

The demon lord will revive. - Tarou ga Hanako to hanashita

太郎が花子と話した

Tarou talked with Hanako.

Thus Japanese sentences follow a very simple pattern of noun, particle, noun, particle, noun, particle, and then, at the end of the sentence, the predicate.

There are various types of predicates in Japanese, and they can be inflected (conjugated) to various forms. The form that's normally considered the "default" one is called the nonpast form. The part of a word that can be inflected is always written in hiragana.

All Japanese verbs in nonpast form end in the ~u vowel, i.e. they end in ~u ~う, ~ku ~く, ~gu ~ぐ, ~bu ~ぶ, ~su ~す, ~tsu ~つ, ~nu ~ぬ, ~mu ~む, or ~ru ~る. Often, it will be ~ru.

- Doragon φ, Ie wo Kau

ドラゴン、家を買う

The Dragon Buys a House.

The Dragon Will Buy a House.

- kau - a verb, "to buy."

As you can see above, a predicate in nonpast form can mean either present tense ("buys") or future tense ("will buy"). It can't be past tensed ("bought"), hence why the form is called nonpast form.

See the article about Tense for details.

Verb words come in two types, the godan verbs (which sometimes end in ~ru) and the ichidan verbs (which always end in ~ru). These two types are conjugated differently but otherwise work identically. Besides these, there's a somewhat different type called suru verbs.

A suru verb is composed of a noun (called the verbal noun) plus the auxiliary verb suru する.

- Sekai Saikou no Ansatsusha φ, Isekai Kizoku ni Tensei suru

世界最強の暗殺者、異世界貴族に転生する

The World's Strongest Assassin Reincarnates Into a Noble of Another World.- tensei - "reincarnation," verbal noun.

- tensei suru - "to do a reincarnation," "to reincarnate."

Note: suru has other uses besides the above. See the article about suru する for details.

In grammar, an auxiliary is so-called because it only adds meaning to something else and can't be used on its own. This means that when suru is an auxiliary it always comes with a verbal noun. Just like auxiliaries in English, sometimes this essential part is missing from the sentence, and its absence is a null anaphor: that is, it isn't said because it refers to something said immediately before.

- mou kekkon shita?

もう結婚した?

Did [you] marry already?- kekkon - verbal noun.

- shita - auxiliary suru.

- mada φ shite-nai

まだしてない

[I] still have not φ.- Here, just like the Japanese auxiliary shite-nai is missing its verbal noun, the English auxiliary verb "have not" is missing its main verb. In both cases, this absence (null) occurs because what's missing is supposed to be what was said just before (anaphor). In other words, it means the same thing as:

- mada kekkon shite-nai

まだ結婚してない

[I] still have not married.

Next we have the copula da だ. This copulative verb always comes after a "noun," meishi 名詞, or a type of adjective called keiyou-doushi 形容動詞, literally "adjectival verb," or a word inflected similarly.

- sore wa fukanou da

それは不可能だ

That is impossible.- fukanou - adjective.

- sore wa inu da

それは犬だ

That is a dog.- inu - noun.

Note: the dano だの particle looks like da だ but isn't. Meanwhile, dato だと, datte だって, daga だが, dashi だし may sound like a single word but are composed of the da だ copula plus something else.

There are countless variants of this da だ copula. For example, de aru である means the same thing as da だ, but its used more in narration, not in dialogue. The phrase de gozaru でござる also means the same thing, but it's mainly used by samurai in anime, and not real people. There are also the polite variants desu, de arimasu, and de gozaimasu. There are dialectal variants and fantasy variants.

There is even a null copula that can replace da だ. In fact, most of the time da だ isn't used at all, the null copula is used instead.

- sore wa fukanou φ

それは不可能

That is impossible. - sore wa inu φ

それは犬

That is a dog.

Notably, nani φ? 何?, "what is [it]?" gets contracted to nan~ when a non-null copula is used, e.g. nani da becomes nanda なんだ, nani desu becomes nandesu なんです, and so on. Do note these could also be contractions of na no da なのだ and na no desu なのです instead, which mean something else.

The last type of predicate is another type of adjective, called keiyoushi 形容詞, literally "adjective" in Japanese. These end in an ~i ~い copula in nonpast form, so they're known as i-adjectives.

- kare wa tsuyoi

彼は強い

He is strong.

Note: some words that end in ~i that you can hear aren't this type of adjective as the ~i isn't the ~i ~い copula, e.g. kirei da 綺麗だ, "to be pretty," kirai da 嫌いだ, "to hate."

These adjectives often have their ending contracted in manga. For example:

- kare wa tsuee

彼は強ぇ

Above, ~oi was contracted into ~ee. For reference, other contractions:

| Contraction | Root |

|---|---|

| tsuee 強ぇ kakkee かっけー |

tsuyoi 強い kakko-ii かっこいい |

| janee じゃねぇ koee 怖ぇ |

janai じゃない kowai 怖い |

| samii 寒ぃ warii わりー |

samui 寒い warui 悪い |

It's not possible to replace this ~i by a null copula like it's done with da だ. However, although unusual, it's possible for the ~i to get clipped, e.g. someone says tsuyo, and everyone knows what that means, but you can't write it in a serious article because it's not considered proper Japanese. Also, a word like kawaii which ends in a long vowel, may get the whole vowel clipped, not just the ~i copula, and you'd end up with something like kawa.

Anime: Zombieland Saga: Revenge (Episode 6)

- Context: a random social media user comments on the legendary Yamada Tae, who is also known by the pseudonym "number 0," zero-gou 0号.

- zero-gou φ kami-kawa!!!!!!!

0号神かわ!!!!!!!

Number 0 is super cute!!!!!!!- kami

神

God. Deity.

Epic. Super. Top-level. (slang.)

- kami

Double Subject Sentences

In Japanese, some predicates have two subjects, called "large subject" and "small subject," where the predication of the small subject somehow also predicates the large one.

Despite there being two subjects, which could be marked by ga が, sentences generally have one topic, which is marked by wa は instead, so in practice you often end up with a __ wa __ ga __ 〇〇は〇〇が〇〇 pattern.

A common example is qualifying body parts, since the body part is intrinsically related to a person. Observe:

- erufu wa {mimi ga nagai}

エルフは耳が長い

{"Long" is true about "ears"} is true about "elves."

{Ears are long} is true about "elves."

Elves have long ears.

Elves' ears are long.- erufu - large subject.

- mimi - small subject.

Such sentences sometimes don't translate literally:

- Tarou wa {atama ga ii}

太郎は頭がいい

{Head is good} is true about Tarou.

Tarou's head is good.

Tarou is smart.

Another confusing scenario is that predicates describing mental states (cognitions) translate to English as cognitive verbs. Observe:

- Tarou wa {piza ga suki da}

太郎はピザが好きだ

{Pizza is liked} is true about Tarou.

Tarou likes pizza. - Hanako wa {kumo ga kowai}!

花子は蜘蛛が怖い!

{Spiders are scary} is true about Hanako.

Hanako fears spiders.

Hanako is afraid of spiders.

Nulls may occur in such sentences.

- φ {piza φ suki desu ka}?

ピザ好きですか?

{Pizza is liked} is true about [you]?

Do [you] like pizza? - φ {φ suki φ}

好き

{[Pizza] [is] liked} is true about [me].

[I] like [pizza].

[I] do φ.

Inflections

In Japanese, predicates can be inflected to all sorts of forms, including past tense, negative, conditional, and so on.

Some of these inflections work by adding a suffix called a jodoushi 助動詞 to some form of the predicate. Notably, the ~ta ~た jodoushi expresses past tense, while the ~nai ~ない jodoushi expresses the negative.

This means if you see ~nai at the end of a sentence, that likely translates to "not" in English somehow:

- tomato wa yasai janai

トマトは野菜じゃない

Tomato is not a vegetable.

Tomato isn't a vegetable. (contraction.) - kare wa tsuyokunai

彼は強くない

He isn't strong. - doragon wa ie wo kawanai

ドラゴンは家を買わない

Dragons don't buy houses.

Meanwhile if you see ~ta ~た at the end of a sentence, that likely translates to past tense. This ~ta ~た becomes ~da ~だ in some godan verbs' conjugations.

- kare wa tsuyokatta

彼は強かった

He was strong. - kare wa shinda

彼は死んだ

He died.

In English, if we want future tense we use the auxiliary verb "will," and if we want both future tense and negative, we use "will not," which contracts to "won't." In Japanese, a similar thing occurs: we can combine suffixes together.

The ~nai suffix, as hinted by it ending in ~i ~い, can be conjugated like an i-adjective, and i-adjectives can be conjugated to past form which adds the ~ta ~た suffix to them somehow, hence, it's possible to have a negative past form like this:

- kare wa tsuyokunakatta

彼は強くなかった

He was not strong.

This whole suffixing suffixes to suffixes process can make predicates into dauntingly long words. But don't worry. It's pretty much always the same suffixes used in the same order.

Everything that's negative and past ends in ~nakatta in Japanese, just like everything that is future and negative starts with "won't" in English.

Not all forms end in a jodoushi. For example, ~nakatta above is suffixed to tsuyoku~. This tsuyoku is the ren'youkei 連用形, "continuative form," of tsuyoi. In essence, a word that ends in ~ku is likely the ren'youkei of an i-adjective. One theory for this is that, originally, the word was tsuyoki 強き, and then the ~k~ stopped being pronounced.

Not all forms exist for all types of predicates. The copulas (da, ~i) have fewer forms than the typical verb. For example, the meireikei 命令形, "imperative form," of kau is kae 買え. There's no such form for the copulas, at least not anything that's used in modern Japanese (technically ~kare would be a meireikei for i-adjectives, for example, but that's simply not used the way the other meireikei are).

This article won't get in detail about how every form is conjugated exactly. For reference, a list of common ways a predicate may end as. It doesn't list every possible ending or every possible function of each ending. It's just an overview:

| Ending | Meaning | Example |

| ~u ~う ~i ~い da だ |

Plain nonpast form. | yurusu 許す [I] allow [it]. [I] forgive [you]. |

| ~masu ~ます desu です |

Polite nonpast form. | yurushimasu 許します |

| ~e ~e ~ro ~ろ koi 来い seyo せよ |

Imperative. meireikei 命令形. |

yokorobe, shounen. 喜べ少年 Rejoice, boy. |

| ~i ~i ~e ~e |

ren'youkei 連用形 Noun form. |

kimi no negai wa youyaku kanau 君の願いはようやく叶う Your wish will finally be realized. |

| ~ku ~く ni に |

ren'youkei 連用形 Adverbial form. |

{yasashiku} naderu 優しく撫でる To caress {gently}. |

| ~eru ~eる ~reru ~れる ~rareru ~られる dekiru できる |

Potential. "Can." |

yatto nemureru やっと眠れる [I] can finally sleep. |

| ~areru ~aれる ~rareru ~られる |

Passive. | korosareru!!! 殺される!!! [I] am going to be killed!!! (help!!!) |

| ~nai ~ない | Negative. "Not." |

ore wa akiramenai 俺は諦めない I won't give up. |

| ~ta ~た ~da ~だ |

Past. "Did." |

akirameta 諦めた [I] gave up. |

| ~te ~て ~de ~で |

te-form. Connective. "And." |

{ie ni kaette} neru 家に帰って寝る [I] {will go back home and} sleep. |

| ~tara ~たら ~dara ~だら |

tara-form. Conditional. "If." |

yokenakattara shinde-ita 避けなかったら死んでいた [I] would have been dead if [I] hadn't evaded [it]. |

| ~tari ~たり ~dari ~だり |

tari-form. Examples. |

manga yondari, anime mitari suru 漫画読んだりアニメ見たりする Reading manga, watching anime, [stuff like that]. |

| ~tai ~たい | tai-form. "Want." |

kanojo ni fumaretai 彼女に踏まれたい [I] want to be stepped on by her. |

| ~ba ~ば | ba-form. Conditional. |

hito wa {korosarereba} shinu 人は殺されれば死ぬ People die {when [they] are killed}. |

| ~zu ~ず | zu-form. "Without." |

nanimo kangaezu 何も考えず Without thinking anything. |

| ~u ~う | Volitional form. "Let's." |

ikou 行こう Let's go. |

| ~sa ~さ | sa-form. "~ness." |

omosa wa nan-kiro? 重さは何キロ? [Its] heaviness is how many kilograms? How heavy is it? What is its weight? |

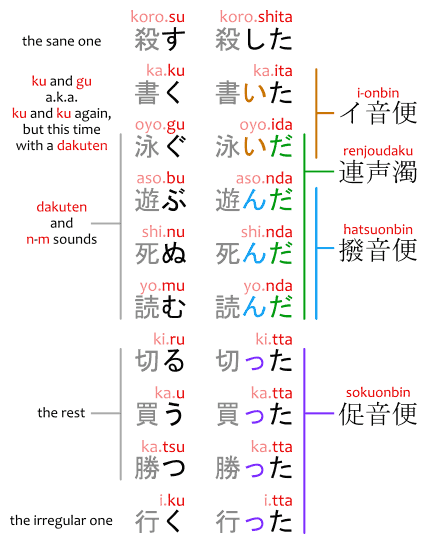

The ~ta, ~te, ~tara, and ~tari forms differ a lot across godan verbs depending on its ending in nonpast form, but they share the same stem. For example, for shinu, the past form is shinda, so you keep the stem shin~ and just replace the ~da: shinde, shindara, shindari. Meanwhile, for kaku, it's kaita, so you keep kai~ and replace ~ta: kaite, kaitara, kaitari.

See onbinkei 音便形 for details.

Besides the above there are some suffixes that you frequently find only in some specific contexts.

- Characters that speak archaically may use ~nu ~ぬ or ~n ~ん instead of ~nai, e.g. akiramenu 諦めぬ. Although some expressions still use these even in modern Japanese, e.g. shiran 知らん, "[I] don't know," keshikaran 怪しからん, "improper" (often translates to "lewd" in anime).

- Some regional dialects have their own jodoushi, e.g. nanimo dekihen 何もできへん is kansai 関西 dialect for nanimo dekinai 何もできない, "can't do anything.".

The way a sentence ends is called gobi 語尾 in Japanese, and this includes not only the inflection but also sentence ending particles and the predicate. In anime, it's not unusual for characters to have all sorts of weird gobi just make the character more characteristic.

- Talking cats and cat girls may end their sentences with nyaa にゃー, "meow." Similarly, dog characters may end theirs with wan わん, "woof."

- sou da nya

そうだにゃ

That's right, meow. - sou da na

そうだな

- sou da nya

- Samurai often use gozaru ござる instead of aru ある. And nerds (otaku オタク) that are particularly socially inept may do so, too.

- sessha wa bushi de gozaru

拙者は武士でござる

I'm a warrior.

- sessha wa bushi de gozaru

- Old men, old kings from medieval fantasy-themed series, may say ja じゃ instead of da だ, and so sometimes do characters that look like a 10 year old girl but are actually 500 years old.

- yuusha yo, {maou wo taosu} no ja!

勇者よ、魔王を倒すのじゃ!

Hero, {defeat the demon lord}!

- yuusha yo, {maou wo taosu} no ja!

- In a red-light district in Edo 江戸 (called Tokyo 東京 today), very long ago, prostitutes were known to say arinsu ありんす instead of arimasu あります, and now you have characters like Shalltear (Overlord) and Yugiri (Zombieland Saga) that speak similarly.

- soutei-gai de arinshita

想定外でありんした

[It] was outside of what was expected.

I didn't expected that.

- soutei-gai de arinshita

There are several ways to form an imperative sentence in Japanese. An imperative sentence is one that orders someone to do something. .For example, for kau, "to buy," all of the below are or can be imperative—they would be telling someone to go "buy" something:

- kae 買え - meireikei.

- katte 買って - te-form.

- kainasai 買いなさい - ren'youkei + nasai なさい.

- kai na 買いな - ren'youkei + na な.

Note: they can also mean other things sometimes, e.g. uso tsuke 嘘吐け, "[you] spew lies," "[you] liar!" uses the meireikei of tsukeru 吐ける but isn't a command.

- Context: a slug panics over a deadly salt-sprinkling old man.

- yamete yo~'

やめてよーっ

Stop~! - shinitakunai yo~'!!

死にたくないよーっ!!

[I] don't want to die! - yoshi na...

よしな・・・

Stop [it]...- yoshi - from yosu 止す, "to stop." Normally you see it as yose yo よせよ, "stop [it]," instead.

Besides the above, the following ia negative imperative, meaning "don't buy:"

- kau na 買うな - nonpast form + na な.

The negative form suffix, ~nai, isn't only a jodoushi. Technically, it's only a jodoushi when suffixed to verbs. When suffixed to adjectives it's an auxiliary adjective. It's also a standalone adjective which is the irregular negative form of the verb aru ある.

- okane ga aru

お金がある

[I] have money. - okane ga nai

お金が無い

[I] don't have money.

Just like the negative tsuyokunai is the ren'youkei tsuyoku plus ~nai, the past form tsuyokatta originates from tsuyoku plus aru conjugated to the past form atta: tsuyoku-atta. Although rare, some sentences have the verb aru ある instead:

- yasuku wa aru ga...

安くはあるが・・・

[It] is cheap, but... (insert some reason why it sucks here.)

The negative of da だ, "is," is janai じゃない, "is not." This occurs because da だ is a contraction of de aru である; this aru is an auxiliary verb, so you can put wa は before it: de wa aru ではある; the negative of aru is nai, so you have de wa nai ではない; and this de wa では is contracted to ja じゃ, so you finally arrive at janai.

Essentially, da and de aru both mean "is," while janai and de wa nai both mean "is not." It's merely that one is a contraction of the other. The contracted forms tend to be used in speech, while the original forms would be literary instead, getting used more in essays.

Auxiliaries and Compounds

Besides jodoushi, another complicated way for a sentence to end is with a word formed by multiple predicate words. These come in two types:

- hashiri-hajimeru

走り始める

To start running. - hashitte-iru

走っている

To be running.

The first type are called "compound verbs," fukugou-doushi 複合動詞, while the second are actually called "auxiliary" in Japanese, e.g. hojo-doushi 補助動詞, "auxiliary verb." There are also auxiliary adjectives.

Note that not all compounds have a word that works like an auxiliary. There cases where both verbs in the compound have equal importance, and you couldn't say one is the auxiliary of the other. Observe:

- uchi-kaesu

撃ち返す

To shoot-return.

To shoot back.- Here, kaesu is an auxiliary, since it modifies how shooting is done..

- uchi-korosu

撃ち殺す

To shoot-kill.

To kill by shooting.- Here, utsu is an auxiliary, since it modifies how killing is done.

- age-sage

上げ下げ

Raising and lowering.- Here, both ageru and sageru are equally important, so neither is an auxiliary. This is also known as a dvanda compound.

- Note that in this case we don't use it as a verb directly, neither age nor sage morpheme get the ~ru morpheme that would identify it as a verb. Instead, this compound word derived from verbs is used as a noun with the auxiliary suru, turning it into a suru-verb:

- baaberu wo age-sage suru

バーベルを上げ下げする

To do "raising and lowering" with a barbell.

To raise and lower barbells. (i.e. lifting barbells to exercise.)

For adjective roots, the suffix replaces the copula:

- kawai-sugiru

可愛すぎる

To be too cute.- kawai-i became kawai-sugiru.

- kirei sugiru

綺麗すぎる

To be too pretty.- kirei da became kirei sugiru.

It's possible to combine both types.

- koware-kakete-iru

壊れかけている

[It] is about to break.

Many expressions that in English would get a word before the predicate get in Japanese a word after the predicate, although not necessarily as an auxiliary technically, further cementing how backwards this language is. For example, the follow expressions translate to "should" and "may."

- {nigeru} beki da

逃げるべきだ

[We] should {run away}. - micha dame!

見ちゃだめ!

[Don't look]!- Same as:

- mite wa dame da

見ては駄目だ

Looking is no good. (literally.)

[You] should not look.

- kiite ii?

聞いていい?

Is asking good? (literally.)

May [I] ask [you] [something]?

Ergativity

An ergative verb is one that can be used both intransitively (with just a subject) and transitively (with subject and object). For example:

- tobira ga hiraku

扉が開く

The door opens. - Tarou ga tobira wo hiraku

太郎が扉を開く

Tarou opens the door.

As a general rule, the intransitive sentence expresses "A did B," while the transitive one expresses "A did B and C caused it." Above, the door opens in both sentences, but only in the transitive sentence it's also expressed that Tarou caused this to happen.

English has many ergative verbs, many verbs that can be used both transitively and intransitively. Japanese, on the other hand, has so few of these that it makes more sense to assume a verb can only be used transitively or intransitively, but never both.

- Tarou ga hon wo moyasu

太郎が本を燃やす

Tarou burns books. - *hon ga moyasu

本が燃やす

Wrong. Intended: "the book burns."

A sentence such as the above may still be valid with a null object, however:

- hon ga φ moyasu

本が燃やす

Books burn [it].- Here we're saying books burn something, so "books" is subject of a transitive "burn" verb, so that's valid.

Instead of ergative verbs, Japanese has ergative verb pairs, as in two verbs, one intransitive, and one transitive. Generally speaking, such pairs translate to one ergative verb in English and share a common root (they start with the same kanji and reading), but this may vary. For example:

- hon ga moeru

本が燃える

The book burns.- moeru is intransitive and forms an ergative verb pair with moyasu.

- *Tarou ga hon wo moeru

太郎が本を燃える

Wrong. Because moeru is intransitive. - Tarou ga moeru

太郎が燃える

*Tarou burns [something]. (wrong.)

Tarou burns. (correct, he is on fire.)

An example of a pair in English would be "to rise" and "to raise."

- Tarou ga te wo ageru

太郎が手を上げる

Tarou raises [his] hand. - netsu ga agaru

熱が上がる

"[His] heat rises."

[His] temperature rises. (i.e. he has fever.)

It's important to note that although such pairs share a same root, there isn't a way to conjugate a word to its intransitive variant or vice-versa. There are no patterns, or rather, there are many patterns but no universal rule. These are practically two separate verbs you have to memorize that mean basically the same thing.

There are cases they're identical in morphological complexity, e.g. kaeru 返る and kaesu 返す, "to return." Some cases the intransitive is simplex, toku 溶く and tokeru 溶ける, "to dissolve." Other cases the intransitive is complex, shizumeru 沈める and shizumu 沈む, "to sink." Others are even more difficult to explain, like obiyakasu 脅かす and obieru 脅える, "to frighten." So there really isn't a simple, straightforward way to tell which is which, or guess what the counterpart would sound like.

Change of Transitivity

Some inflections may change the transitivity of a predicate, which means what was normally marked as object, by wo を, would now be marked as subject by ga が. In particular, this may create double subject constructions for verbs that otherwise wouldn't feature them:

- Tarou ga hon wo yomu

太郎が本を読む

Tarou will read the book. - Tarou ga {hon ga yomitai}

太郎が本が読みたい

{Books are wanted to read} is true about Tarou.

Tarou wants to read books. - kodomo wa {kanji ga yomenai}

子供は漢字が読めない

{kanji are not read-able} is true about children.

Children can't read kanji. - e-hon ga yomi-yasui

絵本が読みやすい

Picture books are easy-to-read.

Passive Voice

The passive voice in English is marked by the pattern "X is/was/will be done Y by Z." Despite this is/was/will be, there is no such copula in Japanese. Instead, the passive is marked by the passive form.

- korosareru!

殺される!

[I] will be killed! (help!!!)

In passive voice, the subject patient is marked by ga が, while the agent is marked by ni に:

- hon ga Tarou ni yomareta

本が太郎に読まれた

The book was read by Tarou.

Japanese has a type of sentence called suffering passive, or indirect passive, where the patient is marked by wo を like in an active sentence, and the subject is somehow affected by the action, often negatively.

In particular, an intransitive verb can't be used in passive voice in English, but can be used in passive voice in Japanese:

- Tarou no tsuma ga shinda

太郎の妻が死んだ

Tarou's wife died. - Tarou ga tsuma ni shinareta

太郎が妻に死なれた

Tarou suffers: [his] wife died.- His wife died, and that affects him somehow.

- ninja ga Tarou no tsuma wo koroshita

忍者が太郎の妻を殺した

Ninjas killed Tarou's wife. - Tarou ga tsuma wo ninja ni korosareta

太郎が妻を忍者に殺された

Tarou suffers: [his] wife was killed by ninjas.

Attributive Clauses

Sentences say stuff about stuff. And one of these two stuffs is a noun. A noun is a word that refers to a thing, like "a cat," or "a dog." But sometimes the noun word alone isn't enough to specify the stuff we're talking about. To be more specific we need to qualify the noun, like this:

- The black cat.

- the - the definite article ("a," "an" are indefinite).

- black - a prenominal adjective, so-called because it comes before the noun.

- bat - noun.

- The cat that is on the table.

- the cat - relativized subject.

- that - relative pronoun, so-called because it introduces a relative clause.

- is on the table - a relative clause.

- The cat wearing a hat.

- wearing a hat - a participal clause, so-called because "wearing" is the present participle of "to wear."

As you can see, we have various ways to qualify adjectives in English, but since we're not here to learn English, we'll make matters simpler and just use relative clauses for everything:

- The cat that is black.

- The cat that is wearing a hat.

In Japanese, there are no relative pronouns. Nouns are qualified by any predicate that comes before it. That is: prenominal clauses are attributive. For example:

- {kuroi} neko

黒い猫

The cat [that] {is black}.

The cat, [which] {is black}.

The {black} cat.

In English we have various relative pronouns, like "that" and "which," and use a comma or pause to separate an nonrestrictive relative clause, which is one that doesn't specify the noun, but merely adds information about.

Since Japanese doesn't have relative pronouns, it's not possible to tell just from the sentence structure which pronoun you're supposed to use in English.

- Hauru no {Ugoku} Shiro

ハウルの動く城

Howl's Castle [that] {Moves}. (does he have another castle that does not move?)

Howl's Castle, [which] {Moves}.

Howl's {Moving} Castle.

The da だ copula can't be used in attributive clauses. When something that would have the da だ copula predicatively is used attributively, something else is used instead.

For nouns, a no の copula is used instead. In this case we'd have a noun qualifying another noun, which is sometimes called "genitive case," so no の is sometimes said to be a "genitive case marker."

- sono boukensha wa erufu da

その冒険者はエルフだ

That adventurer is an elf. - {erufu no} boukensha

エルフの冒険者

The adventurer [who] {is an elf}.

The {elf} adventurer. - {boukensha no} erufu

冒険者のエルフ

The elf [who] {is an adventurer}.

The {adventurer} elf.

This no の copula is ambiguous with the no の particle that works as a possessive marker.

- Context: and elf and a dwarf have each hired an adventurer for some quest.

- erufu no boukensha

エルフの冒険者

The elf's adventurer.

The adventurer of the elf. (as opposed to the one hired by the dwarf.)

For keiyou-doushi, the na な copula is used instead.

- sono hito wa kirei da

その人は綺麗だ

That person is pretty. - {kirei na} hito

綺麗な人

A person [that] {is pretty}.

A {pretty} person.

Based on the grammar above, the adjectives that end in ~i ~い are known as i-adjectives, the ones that get the na な copula are known as na-adjectives, and nouns used attributively are known as no-adjectives.

| Predicative | Attributive | |

|---|---|---|

| Verbs doushi 動詞 |

Ends in ~u vowel. | |

| i-adjectives keiyoushi 形容詞 |

Ends in ~i ~い. | |

| na-adjectives keiyou-doushi 形容動詞 |

Ends in da だ. | Ends in na な. |

| no-adjectives meishi 名詞 |

Ends in no の. | |

Not everything that follows the patterns above falls into the categories above. For example, the phrase ~no you na~ ~のような~, meaning "like," as in "similar to," has you よう conjugated as a na-adjective but being qualified as if it were a noun. In Japanese, it's technically categorized as a rentaishi 連体詞.

See the article about you 様 for details.

Generally speaking, a noun that is relativized can be de-relativized into the topic of a sentence, and vice-versa.

- Re:{Zero kara Hajimeru} Isekai Seikatsu

Re:ゼロから始める異世界生活

Re: Otherworldly Life [that] {[I] Start from Zero}. - sono isekai seikatsu wa ore ga zero kara hajimeru

その異世界生活は俺がゼロから始める

I will start that otherworldly life from zero.

So if you don't understand what a sentence means, it might help to try relativizing or de-relativizing it, and then maybe you'll be able to tell what you're missing.

Exceptionally, some words work exactly like nouns in that they can be qualified, but they can't be de-relativized, e.g. koto こと, tame ため, mama まま. These are sometimes called semantically light nouns.

- yasai wa {kootta} mama

野菜は凍ったまま

The vegetables are still frozen.- Here, mama means a continuing state, so it translates to "still".

The most exceptional case is the no の nominalizer, which is found in a bunch of grammar constructions. When a noun qualifies this no の, the na な copula is used instead.

- {inu na} no de choko wa taberarenai

犬なのでチョコは食べられない

Because {[it] is a dog}, [it] can't eat chocolate. (it could eat other things.)

Adverbs

Adverbs that modify predicates also come before the predicates in Japanese. Unlike other parts of speech, adverbs don't seem to be restrained by any morphological patterns. For example:

- ippai taberu

いっぱい食べる

To eat a lot. - guuzen mitsuketa

偶然見つけた

[I] found [it] by chance.

Above we have lexical "adverbs," fukushi 副詞. They can come right before the predicate without any particle or anything marking them as adverbs. Besides these, we also have the adverbial form of adjectives, which is ~ku ~く for i-adjectives, and the ni に copula for the rest:

- {hayaku} nigeru

早く逃げる

To escape {quickly}.- hayaku - derives from hayai 早い, "to be quick.".

- {sugu ni} nigeru

すぐに逃げる

To escape {immediately}.- sugu ni - derives from sugu da すぐだ, "to be immediate."

There are also some adverbs that come before to と instead, and in some cases this to と is part of the word:

- {shikkari to} hatarake

しっかりと働け

Work {hard}. - chotto matte

ちょっと待って

Wait a bit.

With a very small number of adjectives, like sugoi すごい, it's possible to use them adverbially in nonpast form, although this usage is colloquially considered ungrammatical. See Flat Adverbs for details. For example:

- {sugoku} kawaii

すごく可愛い

[It] is {incredibly} cute. - {sugoi} kawaii

すごい可愛い

Several grammar constructions make use of attributive clauses and the adverbial form of da だ, such that you have an "adverb," but this adverb can be a whole sentence by itself. For example:

- sekai wo sukuu

世界を救う

To save the world. - kore wa {sekai wo sukuu} tame da

これは世界を救うためだ

This is for the purpose [that is] {to save the world}.

This is in order to save the world.- Here, ~tame da predicates the subject kore.

- kare wa {{sekai wo sukuu} tame ni} tatakatte-iru

彼は世界を救うために戦っている

He is fighting {for the purpose [that is] {to save the world}}.

He's fighting in order to save the world.

- Here, ~tame ni modifies the predicate tatakatte-iru.

Before gozaimasu ございます and zonjimasu 存じます, the adverbial form of an i-adjective has a different pronunciation ending in ~u ~う. This change is called u-onbin ウ穏便:

- arigatou gozaimasu

ありがとうございます

Thank you.

- From *arigataku gozaimasu ありがたくございます.

- ari-gatai

有り難い

Hard to have. (literally.) - Likely in the sense of "because it's hard to come by, one should be thankful for it."

- mottai-nou gozaimasu

勿体無うございます

[Such a waste].- Same as mottai nai 勿体ない.

Tensed Predicates

In Japanese, predicates only have two morphological tenses: past form and nonpast form. The past form is when you have a ~ta ~た jodoushi, and the nonpast form is otherwise. The way these two forms work is a bit complicated.

| ∅ Nonpast. |

~ta ~た Past. |

|---|---|

| omou 思う Think. |

omotta 思った Thought. |

| oyogu 泳ぐ Swims. Will swim. |

oyoida 泳いだ Swam. |

| heiwa da 平和だ Is peaceful. |

heiwa datta 平和だった Was peaceful. |

| tanoshii 楽しい Is fun. |

tanoshikatta 楽しかった Was fun. |

| heiwa janai 平和じゃない Isn't peaceful. |

heiwa janakatta 平和じゃなかった Wasn't peaceful. |

| heiwa de wa nai 平和ではない |

heiwa de wa nakatta 平和ではなかった |

The nonpast form is in many ways similar to the simple present in English:

- kyoka suru

許可する

[I] permit [it]. - watashi wa shinjiru

私は信じる

I believe [it]. - mainichi koko ni iru

毎日ここにいる

[I] am here every day. - mainichi undou suru

毎日運動する

[I] exercise every day. - garasu wa moenai

ガラスは燃えない

Glass doesn't burn.

The nonpast form translates to the infinitive in lists of steps to perform a task, and in labels on buttons in user interfaces:

- Context: a recipe.

- shio wo ireru

塩を入れる

Add salt. ("put salt in.") - Context: there's a button in an online shop.

- kaato ni ireru

カートに入れる

Add to cart. ("put into the cart.")

Exceptionally, buttons labelled by suru-verbs may have just the verbal noun instead, e.g.: kensaku 検索, "search," instead of kensaku suru 検索する.

The nonpast form is called "nonpast" because two tenses are expressed through it, however, it doesn't express either tense ambiguously. Only eventive verbs are understood as future perfective in nonpast form, stative predicates are present-tensed only.

- hon wo yomu

本を読む

[I] read books. (present habitual.)

[I] will read a book. (future perfective.) - ringo wa banana to chigau

りんごはバナナと違う

An apple differs from a banana. (present continuous)

*An apple will differ from a banana. (wrong.)

Above, we don't have a "will differ" interpretation because chigau is a stative verb. There's nothing in its morphology that indicates whether it's stative (they look just like any other verb). Instead, it's differentiated by semantics: verbs that express thoughts, existence, relationships, and potentiality are stative.

- hon ga yomeru

本が読める

[I] can read books.

*[I] will be able to read books.- yomeru - "can read" is stative despite being derived from the eventive yomu.

Stative predicates include stative verbs, copulas, and the habitual interpretation of eventive verbs. For these, you would need a futurate or the phrase ~ni naru ~になる to make them future-tensed.

- ore wa kaizoku-ou da

俺は海賊王だ

I am the king of pirates.

*I will be the king of pirates. - ore wa {kaizoku-ou ni} naru

俺は海賊王になる

I will be {the king of pirates}.

I will become {the king of pirates}. - ashita, ore wa kaizoku-ou da

明日、俺は海賊王だ

Tomorrow, I am king of pirates. - {{hon wo yomu} you ni} naru

本を読むようになる

[I] will become {such way [that] {reads books}}.

[I] will start reading books.

As you can see above, the nonpast form may also translate to the present participle (yomu to "reading"). There aren't participles in Japanese, so when this happens it's a mere coincidence.

In particular, you can't take a participle in English like "reading" and figure out which word to use in Japanese, because there multiple forms that can result in this translation. For instance, the noun form:

- kanji no yomi-kaki

漢字の読み書き

The reading and writing of kanji.- yomi-kaki is the noun form of a dvandva compound verb formed by yomu, "to read," and kaku 書く, "to write."

The Japanese ~te-iru form has the stative verb ~iru defining the tense of the predicate. This means an eventive verb in this form is essentially stativized, i.e. a verb that normally would be future tensed becomes present tensed in ~te-iru form. This form has various functions, such as:

- ano hito ga hashitte-iru

あの人が走っている

That person is running.

- hashiru - "to run," eventive verb.

- kabin ga kowarete-iru

花瓶が壊れている

The vase is broken.

- kowareru - "to break," eventive verb.

- juu-kiro wa hashitte-iru

10キロは走っている

Ten kilometers, [I] have run. - kinou kara koko de hataraite-iru

昨日からここで働いている

[He] has been working here since yesterday.

- hataraku - "to work," eventive verb.

The important thing to note about the above is that this form can translate to "is" in English, even though it's not a copula like desu.

In particular, some eventive Japanese verbs that are normally used in ~te-iru form have only a stative translation in English, so the difference between the ~te-iru form and the nonpast form becomes confusing:

- hashi ga koware-kakete-iru

橋が壊れかけている

The bridge is about to break.- koware-kakeru - this means "to be about to break," but it's an eventive verb, so in practice in nonpast form it means "will be about to break (in the future)."

- sushi wo tabetagatte-iru

寿司を食べたがっている

[He] wants to eat sushi.- tabetagaru - this means "to want," in the sense of someone else looking like they want to do something, and it's an eventive verb, so it can only mean they will look so in the future, and it's ~te-iru that makes it present-tensed.

The ~te-iru form can be used with stative predicates as well. In this case, the function ~te-iru perform is to turn gnomic statives into episodic statives.

Essentially, a gnomic stative describes what something is as a concept in the mental world, while an episodic stative describes a property that holds true at a determinate period of time because it's observable in the physical world.

In its simplest usage, ~te-iru is used with a gnomic stative when what's currently observable is opposite to what you would assume to be true. For example:

- Tarou wa oyogeru

太郎は泳げる

Tarou can swim. (gnomically.)- We KNOW he can. That's just the sort of person he IS. He IS someone who can swim. That's his nature.

- Tarou wa oyogete-iru

太郎は泳げている

Tarou can swim. (right now.)- Here, using ~te-iru doesn't mean that he can swim generally, but that he is being able to swim currently, contrary to the assumption he wouldn't be a able to.

Above, "currently" or "right now" is the implied determinate time through which the stative predicate holds true. It's implied because the use of ~te-iru with a stative implies an episodic stative, and an episodic stative requires a determinate time, thus ~te-iru ends up implying "right now as opposed to generally."

The past form works in a similar way to ~te-iru in some cases, likely due to ~te and ~ta being related. Observe:

- Tarou wa shinde-iru

太郎は死んでいる

Tarou is dead. (result of him dying.) - {shinda} hito

死んだ人

People [who] {died}.

Dead people. (i.e. people who are dead.)

Like above, in sentences predicating the current state of something, ~te-iru is used, but in the attributive, the past form is used, and the meaning is basically the same.

- {ochita} gomi wo hirou

落ちたゴミを拾う

To pick up the trash [that] {fell}. (literally.)- ochiru - "to fall."

- ochite-iru - "to have fallen." The result of falling may be "to be on the floor."

- Consequently, {ochita} gomi is interpreted as "the trash {on the floor}," as that's the resultant state of it falling.

The past form is used in counterfactual conditionals, where in English we would use "would."

- yokenakattara shinde-ita

避けなかったら死んでいた

If [I] hadn't evaded [it], [I] would have been dead.- Since I did, in fact, evade it, I "am not dead," shinde-inai 死んでいない.

- kasa kaeba yokatta

傘買えば良かった

If [I] had bought an umbrella, [it] would have been good. (literally.)- Fact is I didn't buy an umbrella, so it's bad. In other words, it's raining right now, I'm drenched, and that sucks, all because I didn't buy an umbrella when I could.

The past form can be imperative, although this is rare:

- matta!

待った!

Wait!

Subordinate Tense

In English, tense is always relative to the moment a sentence is spoken, also known as utterance time or absolute tense. In Japanese, the tense of a subordinate clause may be relative to its matrix, so if the subordinate is nonpast tensed, and the matrix is past tensed, the subordinate is still in the past in reference to utterance time. Observe:

- ano hito wa hashitte-iru

あの人は走っている

That person is running.- hashitte-iru - a nonpast predicate.

- {hashitte-iru} hito wo mita

走っている人を見た

The sentence above has two possible interpretations:

- I saw a person [that] {was running (at the time I saw them)}.

- I saw the person [that] {is running (as we speak, that guy in front of us)}.

In other words:

- "Is running" was true when I saw the person. (relative to the event.)

- "Is running" is true as we speak. (relative to the utterance.)

Most likely, the interpretation will be "was running." This is despite the nonpast hashitte-iru being used.

Conversely, a past tensed subordinate clause will likely mean the person wasn't running at the time I saw them, but was running before I saw them, or at some other point in time.

- {hashitte-ita} hito wo mita

走っていた人を見た

I saw a person [that] {was running (before I saw them)}.

I saw the person [that] {was running (before now, that guy that was running in front of us)}.

In particular, beware of nonpast form adjectives with a past tensed matrix:

- {mazui} suupu ga oishiku natta

まずいスープが美味しくなった

#The soup [that] {tastes bad} now tastes good. (wrong.)

#The soup [that] {is bad} became good. (wrong.)

The soup [that] {was bad} became good. (right.)

The {bad} soup became good.- Above, it doesn't make sense for something that IS currently bad to have become good. Or for something frozen to have been warmed, cheap to become expensive, and so on. If it has become something, then it WAS something else in the past.

Parallel Predicates

The te-form and ren'youkei can be used to connect one predicate to another, which generally translates to "and," and may mean that a single subject is predicated by two consecutive predicates. For example:

- Hanako wa {kawaikute} kirei da

花子は可愛くて綺麗だ

Hanako {is cute and} is pretty.

- Hanako wa kawaii plus Hanako wa kirei da.

- Hanako wa {kirei de} kawaii

花子は綺麗で可愛い

Hanako {is pretty and} is cute. - aitsu wa {kane wo nusunde} nigeta

あいつは金を盗んで逃げた

He {stole the money and} escaped.

He {stole the money, and then} escaped.

- aitsu wa kane wo nusunde plus aitsu wa nigeta.

- {mura wo osoi}, ooku no hito wo koroshita

村を襲い、多くの人を殺した

{[He] attacked the village and} killed many people.

{[He] attacked the villages}, killing many people.

Both te-form and ren'youkei are tenseless: these forms do not express tense on their own. Instead, they just mean something happens or has happened simultaneously with the predicate that comes after them, which consequently means they'll have the same tense as of that predicate.

For example, above, nusunde translates to "stole" in past tense because nigeta is past tensed. If it was nonpast, the translation of nusunde would change to match:

- aitsu wa {kane wo nusunde} nigeru

あいつは金を盗んで逃げる

He {will steal the money and} will escape. - mura wo osoi, ooku no hito wo korosu

村を襲い、多くの人を殺す

[He] will attack the villages, and kill many people.

Similarly:

- Hanako wa {kirei de} kawaikatta

花子は綺麗で可愛かった

Hanako {was pretty and} was cute.

Respectful Predicates

In Japanese, predicates have respectful variants that have exact the same meaning but that culturally are used in contexts that require "respect" for some reason. The simplest example of this respectful language is the "polite language," teineigo 丁寧語, which refers to the use of ~masu and desu.

| Polite form. | Plain. | |

|---|---|---|

| Nonpast. | yomimasu 読みます |

yomu 読む |

| kirei desu 綺麗です |

kirei da 綺麗だ |

|

| kawaii desu 可愛い |

kawaii 可愛い |

|

| Past. | yomimashita 読みました |

yonda 読んだ |

| kirei deshita 綺麗でした |

kirei datta 綺麗だった |

|

| kawaikatta desu 可愛かったです |

kawaikatta 可愛かった |

|

| Negative. | yomimasen 読みません |

yomanai 読まない |

| kirei de wa arimasen 綺麗ではありません |

kirei de wa nai 綺麗ではない |

|

| kirei ja arimasen 綺麗じゃありません |

kirei janai 綺麗じゃない |

|

| kawaikunai desu 可愛くないです |

kawaikunai 可愛くない |

|

| Negative past. | yomimasen deshita 読みませんでした |

yomanakatta 読まなかった |

| kirei de wa arimasen deshita 綺麗ではありませんでした |

kirei de wa nakatta 綺麗ではなかった |

|

| kirei ja arimasen deshita 綺麗じゃありませんでした |

kirei janakatta 綺麗じゃなかった |

|

| kawaikunakatta desu 可愛くなかったです |

kawaikunakatta 可愛くなかった |

As you can see above, words get looooooooooong. Longer is synonymous with more polite, apparently. If your tongue hurts, that means respect. Anyway, there are a few things worth noting about the above.

First, desu です is normally a nonpast form (derived from de aru, which is nonpast), but when used with i-adjectives, it doesn't express tense anymore. Basically, i-adjectives don't have a polite form. To make them polite language, you literally just throw desu after the word, and awkwardly this desu isn't conjugated anyhow, only the i-adjective is.

So in kawaikunakatta desu, we have the negative past of kawaii, and that's not polite, then we throw a desu at the end, and now it's polite. In other words, although desu normally means "is," in this case it means nothing, and kawaikunakatta desu means the same thing as kawaikunakatta: "was not cute."

Note: desu desu ですです is a slang that's basically a cute way of agreeing "yes, yes."

Besides desu, the following are also polite copulas:

- de arimasu

であります

From de aru である, more formal than desu. - de gozaimasu

でございます

From de gozaru でござる, considered more polite than de arimasu.

The ~masu suffix is suffixed to the ren'youkei of verbs, which makes the ren'youkei its stem (some resources may even call it the "-masu stem"). All polite forms take the same stem—you can replace ~masu by ~masen every time. To get the plain form from the polite one:

- For godan verbs, the ren'youkei ends in ~i, so if you see a word like sagashi-masu 探します, you remove the ~masu to get sagashi, then change the ending to the ~u vowel (sa-shi-su-se-so さしすせそ), and now you got the plain nonpast form sagasu 探す, "to search."

- For ichidan verbs, the ~ru ~る is removed in the ren'youkei, so if you see oshie-masu 教えます or kari-masu 借ります, you remove the ~masu to get oshie, kari, then you add the missing ~ru ~る to get the plain nonpast form oshieru 教える, "to teach," kariru 借りる, "to borrow."

- shimasu します and kimasu 来ます are the polite forms of the irregular verbs suru する and kuru 来る, "to come."

There are a few verbs ending in ~aru ~aる that are conjugated to ~ai ~aい instead.

- irassharu

いらっしゃる

To come. - irasshaimasu

いらっしゃいます

In these cases, removing the ~masu and keeping only the modified root is synonymous with the imperative form.

- irasshaimase

いらっしゃいませ

Come [in].

- Expression used when welcoming someone in a store.

- irasshai

いらっしゃい

In Japanese culture, polite language is generally used in school when talking to teachers, in workplaces, when talking to clients, business partners, etc. It's used all the time. If you play an online game, even messages from a game company to players about server maintenance, etc., will be written in this manner of speech.

The "politeness" in this manner of speech depends on whom you're talking with (i.e. it's deictic), not whom you're in the presence of. For example, if the king, a noble, and a servant are in the same room. The noble would speak politely toward the king, but non-politely toward the servant. In anime, it's a trope to have a character who always speaks non-politely because everyone is below them to suddenly speak politely with a new character when they're introduced to mean that new character is even higher ranking than them.

Some characters always speak politely in this way, e.g. ojousama お嬢様 characters, while others never do. Very young children who have never been to school speaking politely for the first time or characters that grew up in gangs or among mohawked brutes that are now joining polite society, may end up conjugating the polite form all wrong, e.g. by suffixing ~masu directly to the nonpast form, sagasu-masu 探すます.

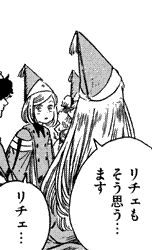

- Context: Riche, a child character not used to speaking politely, tries to speak politely.

- ?Riche mo sou omou... masu

リチェもそう思う・・・ます

I also think so.- Riche uses her own name as first person pronoun, something children do.

- ?omoumasu is a misconjugation of omoimasu 思います. She uses the plain form omou 思う at first, which is how she would normally speak, but a moment later (indicated by the ellipsis), she realizes her mistake and adds the ~masu she forgot about.

- Riche...

リチェ・・・

One sort of accepted polite marker used by younger generations is ssu っす. In anime, this is often used by delinquents in gangs talking to their superiors (their senpai 先輩, their aniki 兄貴, etc.), e.g.:

- sou ssu ka?

そうっすか?

Is that so? - sou desu ka?

そうですか? - kau-ssu

買うっす

[I] will buy [it]. - kaimasu

買います

There are other types of respectful language: the kenjougo 謙譲語, "humble language," and sonkeigo 尊敬語, "honorific language." Essentially, kenjougo says you're trash compared to whom you're talking with, while sonkeigo says they're the greatest dude alive. Okay, not exactly, but that's the gist of it. Some examples:

- o-machi shite-orimasu

お待ちしております

[I] am waiting.- kenjougo variant of matte-iru 待っている.

- shitsurei sasete-itadakitou zonjimasu

失礼させていただきとう存じます

[I] want [you] to let [me] excuse myself. (i.e. "bye.")- kenjougo variant of shitsurei sasete-moraitaku omoimasu 失礼させてもらいたく思います.

- itadaku - humble of morau もらう.

- zonjimasu - humble of omou 思う.

Unlike the polite language, which is deictic and depends on whom you're talking to, sonkeigo is a deference used depending on whom you're talking about. This means if sonkeigo is used, the person it's about is going to be an important person.

- Hanako-hime wa o-yasumi ni narimashita

花子姫はお休みになりました

Princess Hanako [went to sleep].

- o-yasumi ni naru - sonkeigo for yasumu 休む, "to rest," "to sleep."

A tricky part of this deference is that the passive form is used as sonkeigo: