In Japanese, you よう, also spelled you 様, homonymous with ~sama ~様, has several different meanings: it refers to the way something is "like," to say one thing is like another; to say that it's like something that isn't true were true; it can be used to say someone is or isn't the sort of person that would do something, also works for sorts of things; it's used to make future-tensed certain phrases (verbal statives) that would otherwise be present-tensed; it can refer to the desired way things should be that you attempt to cause by doing a certain thing; it's used to say that you have been making yourself do, or not do, something, trying to gain a habit or lose it; it's used in sentences that express wishes, specially in prayers; it's used to say there doesn't seem to be a way to do something; and it's used to express you have made a conclusion based on some evidence but you aren't certain the conclusion is true, you're merely proposing it based on available evidence.

- marude {tenshi no} you da

まるで天使のようだ

[She] is just like an angel.

It's as if [she] is an angel. - {{tori no} you ni} sora wo tobu

鳥のように空を飛ぶ

To fly {like {a bird}}. - {sekai ga owatta ka no} you da

世界が終わったかのようだ

[It] is as if {the world ended}. - {{uso wo tsuku} you na} hito janai

嘘をつくような人じゃない

[He] isn't a person {the sort [that] {would lie}}. - Tarou ga {{yasai wo taberu} you ni} natta

太郎が野菜を食べるようになった

Tarou became {in such way [that] {eats vegetables}}.

Tarou started eating vegetables. - {{nigerarenai} you ni} doa ni kagi wo kaketa

逃げられないようにドアに鍵をかけた

{So that {[he] couldn't escape}}, [I] put a lock on the door. - {{uso wo tsukanai} you ni} shite-imasu

嘘をつかないようにしています

[I] have been [trying to] {{not spew lies}}. - yuki ga furimasu you ni

雪が降りますように

[Let it be so that] it snows. - naoshi-you ga nai

直しようがない

There's no way to fix [it]. - douyara {muda no} you da

どうやら無駄のようだ

It seems {it is futile}.

Conjugation

The syntax of you 様 is rather unusual. It's qualified as if it were a noun, but conjugated like a na-adjective. Let's start with how it's conjugated:

| Plain Form | Polite Form | |

|---|---|---|

| Nonpast Form | you da ようだ |

you desu ようです |

| Past Form | you datta ようだった |

you deshita ようでした |

| Negative Form | you janai ようじゃない |

you dewa arimasen ようではありません |

| Negative Past Form | you janakatta ようじゃなかった |

you dewa arimasen deshita ようではありませんでした |

| Adverbial Form | you ni ように |

|

| te-form | you de ようで |

|

Regarding the "qualified like a noun" part, that means in most of its uses the way other words interact with you 様 is the same way they would interact with a noun. Observe:

- tsuki no katachi

月の形

The shape of the moon.

A moon shape. - tsuki no you da

月のようだ

It seems to be the moon.

It's like the moon. - tsuki no you na katachi

月のような形

A moon-like shape.

When we have a noun-noun pattern (a noun qualifying another noun), we normally have a no の between the nouns, but strangely as we can see in the last phrase ~you gets a no between it and its qualifier (tsuki) but not between it and the word it qualifies (katachi), so it's weird like that.

In Japanese grammar, ~you da is classified as a rentaishi 連体詞, the same category as other syntactically-unusual words like onaji 同じ.

Another noun-like behavior of ~you is that you can't use the polite form before ~you, just like you can't use the polite form when qualifying a noun.

- *{hashitte-imasu} hito

走っています人 - {hashitte-iru} hito

走っている人

A person [that] {is running}.

A running person. - *{hashitte-imasu} you da

走っていますようだ - {hashitte-iru} you desu

走っているようです

It seems [he] is running.

Like above, to keep a sentence polite you would use ~you desu instead of ~you da rather than conjugating what comes before to ~masu.

There's an exception, however: with the prayer usage, in which ~you ni comes at the end of the sentence, the polite form is allowed. I guess in this case it's less like a noun and more like a sentence-ending particle.

Grammar

At first glance, the word you 様 sure looks like it refers to the "way" things are, or the "way" something is. After all, consider the ways it's used:

- To compare similarities between the way things are.

- To draw conclusions based on the way things are.

- To cause things to become in a certain way.

- To refer to the ways we can do a thing.

However, in the English word "way" we have two different senses: one is about method while the other is about appearance, and you 様 is only about appearance, not method.

For example, in "the way he dances" we may be referring to the dancer's precise movements, their order, speed, etc., such that we can copy that way, or we may be simply talking about how it looks like, so we can compare it to the way someone else dances.

With you 様 it's always about the latter. It refers to the way things are which we can examine and compare. This is mostly unimportant, but I think it helps understand how the word works.

In particular, phrases in the pattern ~you ga nai aren't about how many separate ways (methods) exist to perform an action, but whether the action APPEARS to be feasible or not at all, so it's all about appearance at some level.

To Be Like

When ~you da ~ようだ is qualified by a noun (~no you da ~のようだ), it may mean "it's like X" in the sense that Y is similar to X somehow. This is called a simile. For example:

- Tarou ga inu no you da

猫が犬のようだ

Tarou is dog-like.

Tarou is like a dog.

- In anime, sometimes a character with an supernatural sense of smell is compared to a dog when they can find people from their scent.

- Not to be confused with being called a "puppy," wanko わんこ, when they're overly attached to a woman and would do anything for her like a dog wagging its tail to its owner.

- kanojo wa marude tenshi no you da

彼女はまるで天使のようだ

It's as if she were an angel.

She's just like an angel.- marude - "entirely." When used with ~you da, it ends up meaning "completely like a...," "exactly as if [it] were a..."

When ~no you da comes before a noun, qualifying it, you'll have ~no you na ~のような instead, its attributive form:

- {inu no you na} hito

犬のような人

A person [that] {is like a dog}.

A dog-like person.

Note that ~no you da ~のようだ only means "like" in the sense of "to be similar," and has nothing to do with other meanings of the English word "like," e.g.:

- Tarou wa {inu ga suki da}

太郎は犬が好きだ

Tarou {likes dogs}. - {inu-zuki na} hito

犬好きな人

A person [that] {likes dogs}.- ~zuki - suki 好き affected by rendaku 連濁.

To Be Like Of

In Japanese, when nouns are used like adjectives qualifying other nouns, they're said to become no-adjectives. This is also called the genitive case. The no-adjectives may express two fundamentally different relationships between the nouns, which we'll call:

- Copulative. IS-A relationship.

A Is a B. - Possessive. IS-OF-A relationship.

A is of a B.

Observe the difference:

- {tenshi no} Hanako

天使の花子

Hanako, [who] {is an angel}.

The angel Hanako. - {tenshi no} tsubasa

天使の翼

Wings [that] {are of an angel}.

Angel wings.

Note that there's no difference in syntax in Japanese between the two, so merely looking at the words, any sentence may have either meaning.

- {akuma no} pawaa

悪魔のパワー

A demon's power. The power of a demon.

The demon Power. Like the character from Chainsaw Man who is called "Power" and is a demon.

Both of these uses apply to ~no you da ~のようだ, like this:

- A is like a B.

- A is like of a B.

For example:

- {tenshi no you na} Hanako

天使のような花子

Hanako, who {is like an angel}.

The angel-like Hanako. - {tenshi no you na} tsubasa

天使のような翼

Wings [that] {are like of an angel}.

Angel-like wings. - {akuma no you na} pawaa

悪魔のようなパワー

The demon-like power.

Power, [that] {is like of a demon}.

The demon-like Power.

[A character named] Power, [who] {is like a demon}.

Although less common, the possessive interpretation is also valid in the predicative. In fact, some times only the possessive one makes any sense at all, which is confusing if you don't know about it:

- {neko no you na} mimi

猫のような耳

Cat-like ears.

Ears {like of cats}. (i.e. same shape as cats have.)

#Ears {like cats}. (each ear appears to be a whole, entire cat.) - sono mimi wa neko no you desu

その耳は猫のようです

Its ears are cat-like.

Its ears are like of cats. (i.e. same shape as cats have.)

#Its ears are like cats. (nonsense again.)

Without this grammar you would end up repeating phrases. Observe:

- {omise no ryouri no you na} ryouri wa tsukurenai

お店の料理のような料理は作れない

[I] can't make food {like the food of the store}.

I can't make the same sort of food a restaurant would make.

I can't cook food as good as the food the store cooks. - {omise no you na} ryouri wa tsukurenai

お店のような料理は作れない

[I] can't make food {like of the store}.

Temporal qualifiers may also be used with ~no you da. For example:

- {tatoe tousen shitemo} {kako no you na} chikara wa ni-do to moranai deshou

たとえ当選しても過去のような力は二度と戻らないでしょう(BCCWJ, Yahoo!知恵袋)

{Even if [he] were elected}, power {like of the past} wouldn't return twice. (literally.)

Even if he were elected, he would never gain power like he had in the past.- ni-do to... ~nai - wouldn't occur twice, would never happen again.

- kako no chikara no you na chikara

過去の力のような力

Power like the power of the past.

Like One Would

When ~you da ~ようだ comes before an adjective or verb, modifying it adverbially, you'll have the phrase ~no you ni のように. Observe:

- {inu no you ni} shippo wo furu

犬のように尻尾を振る

To wag [one's] tail {like a dog would [wag his]}.

To wag one's tail {like a dog would}.

To wag one's tail {like a dog}. - {inu no you ni} kawaii

犬のように可愛い

To be cute {like a dog would be}.

To be cute {like a dog}.

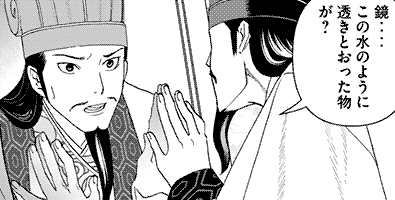

- Context: a man from the past gets reincarnated in the modern world, gets bewildered by a mirror.

- kagami.... kono {{{mizu no} you ni} suki-totta} mono ga?

鏡・・・・この水のように透きとおった物が?

Mirror.... this thing [that] {is clear {like {water}}}? (literally.)- A mirror? This thing is a mirror?

- Here, the character is comparing the properties of the mirror to the properties of the water, except the property is a verb, suki-tooru 透き通る, "to be transparent," "to be clear," in the sense of letting you see through it (hence why tooru 通る, "to go through," is part of the compound verb).

- Considering the sentence, I guess the mirrors he knows about, from thousands of years ago, probably looked different, and weren't as clear as water the way the modern mirror is.

Non-Nominal Likeness

Since all sorts of words can qualify nouns, all sorts of words can qualify ~you ~様. Observe:

- {Tarou to onaji} fuku da

太郎と同じ服だ

?[His] clothes {are identical with Tarou's}. (literally.)

[He] has the same clothes as Tarou. - {{Tarou to onaji} you na} fuku da

太郎と同じような服だ

[He] has clothes the same sort as Tarou.- They're like the same. Similar, but not exactly identical.

Above, onaji comes directly before the noun fuku, so it makes sense that onaji can also come directly before ~you na. Similarly:

- {{samui} you ni} mieru

寒いように見える

[It] looks {like {[it] is cold}}.

[He] looks {as if {[he] is feeling cold}}. - {{kiken na} you ni} kikoeru

危険なように聞こえる

[It] sounds {like {[it] is dangerous}}.

It's also possible to use this ~you ni qualified by verbs, but note that ~you ni qualified by a verb often doesn't have the "like" meaning but a different usage, such as explaining what you intend to achieve by doing something.

When it does mean "like," the tense and aspect of the verb may vary. Observe:

- kou yareba ii

こうやればいい

If [you] do [it] like this, [it] is good. (literally.)

You just have to do it like this, that will be enough. - {{senpai ga yatta} you ni} yareba ii

先輩がやったようにやればいい

If [you] do [it] {the way {senpai did [it]}}, [it] is good.

You just have to do it the way senpai did it.- senpai 先輩 - one's "senior," in general someone who has been doing something for longer than you, and therefore can teach you how to do stuff properly.

- {{senpai ga yatte-iru} you ni} yareba ii

先輩がやっているようにやればいい

You just have to do it the way senpai is doing it.

Above we have the verb yaru やる, "to do [a task]," in past perfective and present progressive forms.

Just like in English, yatta you ni means senpai did something previously and we're copying what they did, while yatte-iru you ni means senpai is currently doing something and we're supposed to mimic them, e.g. if they're dancing or cutting food and you're supposed to do the same.

When the qualifying verb is in nonpast form, things get a bit special because it may refer to an unrealized event (future or subjunctive), which directly would translated to "would," but that may sound weird, so the progress "is ~ing" translation may make more sense. Observe:

- {{sakebu} you ni} utau

叫ぶように歌う

To sing {like {[you] would shout (or scream)}}.

To sing {like {[you] are shouting}}.

A sentence in the structure above means to do one thing the same or similar way as you would do another. It's an analogy. But note that it doesn't mean anybody is singing or shouting right now. It just means that if they were to sing, or when they do sing, it sounds like they are shouting, or screaming.

Counterfactual Analogies

The phrase ~ka no you da ~かのようだ is used in sentences that make exaggerated analogies, more specifically, analogies where you say "it's like it's X," but X either isn't true or we aren't sure it's true. For example:

- Context: something bad happened.

- {sekai ga owatta ka no} you da

世界が終わったかのようだ

It's like {the world ended}.

It's as if {the world ended}.- The world, in fact, hadn't actually ended, but it was as if it had.

Such sentences MUST compare facts (what's really happening) to something that's not factual. In technical terms, they're counterfactual expressions. In particular, considering the "I think" usage of ~you da, just adding ka no completely changes what's conveyed in a sentence:

- {Tarou ga shinda} you da

太郎が死んだようだ

It seems {Tarou died}.- This implies he really IS dead.

- He looks like he is dead, so I guess he must be.

- {Tarou ga shinda ka no} you da

太郎が死んだかのようだ

It's as if {Tarou died}.- This entails Tarou is NOT dead, since "Tarou died" must be contrary to the fact.

- He looks like he is dead; I know he isn't, but it's as if he were.

Typically this usage doesn't show up in the predicative form but instead in the attributive ~ka no you na ~かのような or the adverbial ~ka no you ni ~かのように.

- Tarou wa {{yuurei demo mita ka no} you na} kao wo shite-ita

太郎は幽霊でも見たかのような顔をしていた

Tarou was making a face {like {[he] had seen a ghost}}.- Entailment: he hadn't, in fact, seen a ghost, 'cause ghosts don't exist.

- {{nanimo shiranakatta ka no} you ni} furumatte-ita

何も知らなかったかのように

[He] acted {as if {[he] didn't know anything}}.- Entailment: he knew something, and was merely pretending he did not.

Note that counterfactuality is only "contrary to the facts" that we do know about, or at least, in language, that we pretend to know about when we say stuff. Thus we can have a sentence like this:

- {{nanika shitte-iru ka no} you na} ii-kata

何かを知っているかのような言い方

A way-of-speaking [that] {is as if {[he] knows something}}.- ii-kata - "way of speaking," as in his "choice of words" feel like he knows something.

- Entailment: the facts are that he doesn't know anything.

The sentence above can be used in a context where a character SHOULDN'T know any details about a situation, but talks with a level of certainty that feels like they know something. That is, he knows something he SHOULDN'T know at least according to the facts we have so far.

Simply doubting something is true doesn't make it impossible for it to be usable with ~ka no you ni.

- {{takara-kuji ga atatta ka no} you na} kao wo shite-iru

宝くじが当たった家のような顔をしている

[He] is making face {like {[he] won the lottery}}.- takara-kuji ga ataru - to get the lottery number right, to win the lottery.

- The speaker is making this analogy believing that this isn't the case, that the other person didn't win a lottery, but something with similar level of awesomeness must have occurred to him for him to make that face.

In general, however, ~ka no you ni is used for things that the speaker doesn't believe to be true.

- {{chikyuu ga marui ka no} you na} koto wo iu

地球が丸いかのようなことを言う

[He] says things {as if {the Earth were round}}.- e.g. he says things like doing a full lap around the planet, when, obviously, you'd just fall off when you reach the edge of the map.

Above, the Earth being round is counterfactual, so we can infer that, as far as the speaker is concerned, the Earth isn't round, and they're confused by someone else talking as if that were true, because for them it isn't.

Although I can't find a source on this, there's enough syntactical and semantic reason to believe the ~ka no part of ~ka no you da is the ka か sentence ending particle (the same used when asking questions) followed by the no の attributive copula.

One syntactic reason is that you can't use the da だ copula before ~ka no you ni ~かのように. This would occur because ka か replaces da だ in questions. It doesn't replace desu です, but desu です is generally not used in subordinate clauses.

- kanojo wa tenshi (φ/da/desu)

彼女は天使(/だ/です)

She is an angel. - kanojo wa tenshi (ka/*da ka/desu ka)?

彼女は天使(か/*だか/ですか)?

Is she an angel?- Here, tenshi ka and tenshi desu ka are correct, but tenshi da ka is wrong.

- {kanojo ga tenshi (ka/*da ka/*desu ka) no} you (da/desu)

彼女が天使(か/*だか/*ですか)のよう(だ/です)

It's like {she were an angel}.

One interesting exception is that kano 彼の is an archaic way of saying "that," ano あの, e.g. kano kuni 彼の国, "that country," specially when referring to the country of a third person (not the country of the speaker or the listener).

So it's possible, although extremely unlikely, the kano you ni means "like that way," ano you ni あのように, in some sentence out there. However, it's evident that's not normally what ~ka no you ni means.

First because it's simpler to explain the counterfactuality requirement as being due to the ka か particle than being due to kano かの. And second because if it were kano, then, like ano, it would be qualified by the attributive form, which isn't the case:

- {tenshi no} ano hito

天使のあの人

That person [who] {is an angel}. - {tenshi no} kano you ni

天使のかのように

Like that way [which] {is angelic}.

Like that way {of the angel}.- People don't normally use no の before ~ka no you ni, and that must be because normally it's not the kano word, but ka か particle before no の.

And finally there's this other homonym:

- {{ka no} you na} mushi

蚊のような虫

An insect {similar to {the mosquito}}.- ka 蚊 - "mosquito."

Illogical Temporal Usage

There's a usage of you 様 with temporal qualifiers that appears to make no sense, logically speaking. It's sentences like this:

- {ano koro no you} ni wa modoranai

あの頃のようには戻らない

*[I] won't return to {like that time}.

[Things] won't go back to {like [the way they were] at that time}.

The reason such sentence doesn't make sense, despite being used, is that the verb modoru means "to go back to," and, logically speaking, you can only go back, return, to a point that you have previously been. You can't return to somewhere you haven't been yet. That makes no sense.

And yet, in such sentence you aren't returning to the past, to a certain period of time, you're turning to a period of time LIKE the past. To a way things are that's SIMILAR to how things were, and therefore NOT EXACTLY how things were. So you're "returning" to a way that's never actually been.

It gets more confusing when it's used with first person pronouns. Observe:

- {ano koro no you na} watashi ni wa modoranai

あの頃のような私には戻らない

?[I] won't go back to a me {like of that time}.

?[I] won't return to a way like I was at that time.- Song: 白いGradation - via youtube.com, accessed 2022-08-06.

- Context: a blogger imparts knowledge from personal experience onto his readers, about finding where to live as an university student.

- {kako no you na} boku to onaji shippai wo shinai tame ni mo, {{dekiru} dake hayai} taimingu de oheya-sagashi wo hajimete-kudasai mase.

過去のような僕と同じ失敗をしないためにも、できるだけ早いタイミングでお部屋探しを始めてくださいませ。

?In order to not repeat the same mistake as a me {like of the past}, start searching for a room {as quickly as {[you] can}}.

- Source: 大学生が一人暮らしの部屋を探すタイミング - tatsutsublog.com, accessed 2022-08-06.

I suppose one way to interpret the first sentence is that modoru means "revert" in the sense of "undo progress" rather than simply "return." So the character won't revert to being the same "sort" of person they were before, they've progressed beyond that.

The Sort Of X That Would Do Y

When ~you na ~ような is used after a sentence that describes what someone "does" (a habitual sentence), it's generally used to say "he's the sort of person that would do X," or "he isn't the sort of person that would do X." Observe:

- Tarou wa nakama wo uragiru

太郎は仲間を裏切る

Tarou betrays [his] nakama.

Tarou betrays [his friends].

- Here, "betrays" is said to be in present tense, "habitual" gramatical aspect.

- Tarou wa {{nakama wo uragiru} you na} hito dewanai

太郎は仲間を裏切るような人ではない

?Tarou isn't a person {the sort [that] {would betray [his] friends}}.- You can trust Tarou, he isn't that sorta guy!

- aitsu wa {{nakama wo uragiru} you na} otoko da

あいつは仲間を裏切るような男だ

?He is a man {the sort [that] {would betray his friends}}.- Beware! That guy is scum!

Normally in English it would be weird to say things in this order. You wouldn't say "a man the sort that" or "sort of," you would say "the sort of man that would betray his friends."

In this sort of sentence, ~you na is used, but to say "sort" in general you would say shurui 種類, "sorts," "kinds," or iron'na いろんな or samazama na 様々な, "[there are] various sorts of."

One peculiarity of this usage is that you don't find it in the predicative. That is, if you said:

- *sono otoko wa {nakama wo uragiru} you da

その男は仲間を裏切るようだ

Intended: "that man is the sort that {would betray his friends}."

That wouldn't mean "sort" as it does attributively. It would instead have a "I think" or "I heard that" meaning, which is a different usage of ~you da. So every time you have "the sort that would" usage, you need the pattern:

- {X you na} Y da/janai

〇〇ような××だ/じゃない

[He] is/isn't an Y {the sort that would do X}.

The subject of the sentence doesn't need to be a person. It can be something inanimate:

- {{{kantan ni} shizumu} you na} fune dewanai

簡単に沈むような船ではない

[It] isn't a ship {the sort [that] {would sink {easily}}}.- Something exceptional must have happened for it to sink.

- {{dare demo motte-iru} you na} mono dewanai

誰でも持っているようなものではない

[It] isn't a thing {the sort that {anyone would possess}}.

[It] isn't the sort of thing anyone would have.

- Context: in a traditional JRPG setting, a hero had a party which included an elf. The elf outlived the hero, as elves live longer than human. She tells about what sort of person he was.

- {watashi to wa chigatte} {{hitasura ni} massugu de}, {{{komatte-iru} hito wo kesshite mi-sutenai} you na} ningen deshita.

私とは違ってひたすらにまっすぐで、困っている人を決して見捨てないような人間でした。

{Different from me}, {[he] was [{always} frank] and}, was a human {the sort [that] {wouldn't [abandon] someone {being troubled [by something]}}}.

Unlike me, he was the sort of person that would always help people in trouble.

- hitasura - having only one thing in mind.

- massugu - "completely direct," "completely straight (because a direct line is a straight one)," in the sense not masquerading their intentions or being roundabout about things, just straight going and helping people in this case and it being simply that and nothing more. Also used in the sense of being "honest" as not being "twisted," e.g. not living a criminal life, living a honest one.

- chigatte - te-form of chigau 違う.

- {{watashi dewanaku} kare ga iki-nokotte-ireba}, {ooku no mono wo sukueta} hazu desu.

私ではなく彼が生き残っていれば、多くのものを救えたはずです。

{If {not me but} he had survived}, [he] would have {been able to save many people}.

If he was alive instead of me, he would be able to save many people. (which I didn't saved because I'm not like him).- iki-nokoru - literally "to live and remain," to remain living after an event, to survive. May mean they survived a mortal danger or simply that they're still alive while others are not.

- sukueta - past form of potential form of sukuu 救う, "to save [people]."

- hazu - used to say what one concurs would be true, regardless of whether it's true or not. In this case, she concludes: "[he] could save a lot of people," ooku no mono wo sukueta. This is past-tensed because it's a counterfactual conditional: if he were alive, he could save people, but the facts are he isn't alive, therefore those people weren't saved.

Future Tense of Statives

Sometimes, ~you ~よう is used in sentences that mean "becomes X," "starts doing X," or "stops doing X," specially in the pattern ~you ni naru ~ようになる. This happens when X is a stative predicate that is also a verb. For example:

- Tarou wa oyogeru

太郎は泳げる

Tarou can swim.

Tarou is able to swim.- oyogeru - stative verb.

- Tarou wa {{oyogeru} you ni} naru

太郎は泳げるようになる

Tarou will become {in a way [that] {can swim}}

Tarou will become able to swim.

This usage is probably somehow related to the "sort that would" meaning.

In any case, the reason why this grammar exists is a bit complicated.

In Japanese, there's a form called nonpast form which is used both when a predicate is in present tense or in future tense, but this form isn't really ambiguous between two tenses most of the time.

That's because besides tense there's also grammatical aspect: stative predicates are interpreted as present continuous most of the time, while eventive verbs are either future perfective or present habitual.

- kirei da

綺麗だ

[It] is pretty. (not "will be" pretty.) - kore wo kau

これを買う

[I] will buy this. (future perfective.) - mai-shuu kore wo kau

毎週これを買う

[I] buy this every week. (present habitual.)

To express a stative in the future tense, the verb "becomes," naru なる, is used, and the stative becomes an adverb modifying this verb. Most statives are adjectives, so their adverbial form (ren'youkei 連用形) is used:

- {kaizoku-ou ni} naru

海賊王になる

[I] will become {the king of pirates}.

- {tsuyoku} naru

強くなる

[He] will become {string}.

Basically, since naru is an eventive verb, it has a future tense in nonpast form, so one could say it acts like an eventivizer whose purpose is just to make words that wouldn't normally be interpreted as future tensed future tensed.

However, besides adjective words, there are also statives that are verb words. Verb words don't have an adverbial form, but naru needs the state to be an adverb. So the solution the Japanese language offers us is to simply use ~you ni as an adverbial form equivalent for these words.

Note that ~you ni is the adverbial form of ~you da, so it fills the role of adverb that naru requires.

It's really just that in this case. No complex meaning or anything. Pretty much every time you have a stative that's a verb and you need the future tense, ~you ni gets used, as it's used like a converter to make the syntax work.

As for what are verbal statives, there are two types:

- Stative verbs.

- Habitual predicates.

Stative verbs include the potential form of verbs, e.g. oyogeru, "can swim," which derives from oyogu 泳ぐ, "to swim." This is probably the case you'll see most, but verbs of thought, feeling, and other mental states are also stative. Observe:

- watashi wa sou omou

私そう思う

I think so.

I think that way. - watashi wa {{sou omou} you ni} natta

私はそう思うようになった

I became {such [that] {thinks such way}}.

I started feeling that's how it is. - watashi wa shinjimasu

私は信じます

I believe [it].

I believe [you]. - watashi wa {{shinjiru} you ni} narimashita

私は信じるようになりました

I started believing [it].

I now believe [it].

I came to believe [it].

Habitual predicates come mainly in two kinds: eventive verbs that describe a recurring event (frequentatives), and those that describe a possible event (dispositional).

- Tarou wa mai-asa terebi wo miru

太郎は毎朝テレビを見る

Tarou watches TV every morning. - Tarou wa {{mai-asa terebi wo miru} you ni} natta

太郎は毎朝テレビを見るようになった

Tarou became {in a way [that] {watches TV every morning}}.

Tarou started watching TV every morning.

Above we have a cyclic adverb, "every morning," which describes a recurring event. If Tarou becomes such way that he does the same thing over and over again, we just say in English that he "started" doing it.

Conversely, if the negative form was used, we would say he stopped:

- Tarou wa {{terebi wo minai} you ni} natta

太郎はテレビを見ないようになった

Tarou became {in a way [that] {doesn't watch TV}}.

Tarou stopped watching TV.

So That X Would Happen, I Did Y

The phrase ~you ni ~ように can also be used to say "so that X would happen, I did Y." The way this works is exactly the same as described above, the only difference is that instead naru, we can use any verb with ~you ni.

To elaborate: it's possible to use the adverbial form of a stative followed by a verb to say that doing the verb results in a given state. Observe:

- {fukaku} shizumu

深く沈む

To sink {deep}.- Deep (as in not "deeply") - a flat adverb in English.

- {takaku} tobu

高く飛ぶ

To jump {high}.

To fly {high}.

Both deep and high are the final states after doing a thing, to sink and to jump/fly, respectively.

It follows that the same grammar can be applied to verbal statives so long as we use ~you ni with them.

- {{nani mo mienai} you ni} me wo tojita

何も見えないように目を閉じた

{So [that] {[I] wouldn't see anything}}, [I] closed my eyes. - Context: I put an animal in a box.

- {{iki ga dekiru} you ni} hako ni ana wo aketa

息ができるように箱に穴を開けた

{So [that] {[it] could breathe}}, [I] opened holes in the box.

In fact, any verb appears to just work, including eventive verbs:

- {{wasurenai} you ni} memo shite-oita

忘れないようにメモしておいた

{So [that] {[I] wouldn't forget}}, [I] made a note.- ~te-oku ~ておく - "to do [something] in preparation for later."

The reason for this is likely the "dispositional" interpretation of the habitual: if a sentence says "I'm not disposed to forget" in present tense, that virtually means "I won't forget" in future tense, or "I wouldn't forget" if the need to remember ever arises.

Observe that although this usage translates to English in a completely different way from the usage with naru, what ~you ni means here is actually the same thing. It refers to a "way," in the sense of the way things are, how they look like, how stuff end up as.

The key difference is that in sentences such as the above we have a causation. With naru we're merely saying things ended up in this you 様, but with other verbs we're saying that performing the verb caused the you 様 to become true.

We can observe this clearly by using the most generic verb we can use: suru する, "to do."

The verbs naru and suru form an ergative verb pair: where naru means "X becomes Y," suru means "Z causes X to become Y." Z makes, or lets, X become Y. This applies to ~ku suru ~くする, ~ni suru ~にする, and, naturally, also to ~you ni suru ~ようにする. Observe:

- Hanako ga Tarou wo {ou ni} suru

花子が太郎を王にする

Hanako will cause Tarou to become {the king}.

Hanako will make Tarou the king. - haiboku ga hito wo {tsuyoku} suru

敗北が人を強くする

Defeat causes people to become {strong}.

Defeat makes people {stronger}.

Above we have the states ou da 王だ, "to be king," and tsuyoi 強い, "to be strong," and the sentence expresses that this state is caused, is brought forth, by the subject, marked by ga が, to the object, marked by wo を, by the causer to the causee.

- Tarou ga ishi wo {takaku} mochi-ageta

太郎が石を高く持ち上げた

Tarou held up the stone {high}.- Tarou - causer.

- ishi - causee.

- takaku - state caused by mochi-ageta.

Since ~you ni is nothing but a way for verbal statives to participate in this grammar syntax, it follows that the exact same ideas applies:

- Tarou ga nemurenai

太郎が眠れない

Tarou can't sleep. - Tarou ga {{nemureru} you ni} naru

太郎が眠れるようになる

Tarou becomes {in a way [that] {is able to sleep}}.

Tarou becomes able to sleep. - Hanako ga Tarou wo {{nemureru} you ni} suru

花子が太郎を眠れるようにする

Hanako will cause Tarou to become {in a way [that] {is able to sleep}}.

Hanako will make Tarou become able to sleep.

Typically, however, you won't see a causee marked by wo を like in the sentence above. Instead, you'll see a causer causing a situation, a you 様, that includes the would be causee doing something. For example:

- Hanako ga {{Tarou ga nemureru} you ni} komori-uta wo utau

花子が太郎が眠れるように子守唄を歌う

Hanako will sing a lullaby {(causing the following: {Tarou is able to sleep})}.

So that Tarou can sleep, Hanako will sing a lullaby.

Above, the situation Hanako wants to cause is for Tarou ga nemureru to become true, and she will try to cause it by utau'ing a komori-uta.

When the causing verb is in the ~te-iru form, normally you'll have an iterative sentence, which says the subject has done and will continue doing the same thing so that one thing happens. Observe:

- {{yasai ga {ookiku} naru} you ni}, mai-nichi mizu-yari wo shite-iru

野菜が大きくなるように、毎日水やりをしている

{So that {the vegetables grow {big}}}, [I] water [them] every day.- mizu-yari - "watering," suru-verb derived from mizu wo yaru 水をやる, "to give water to" a plant, in this case.

Above, "to water [them] every day," mai-nichi mizu-yari wo suru, has occurred before and is assumed to continue to occur in the future, hence the ~te-iru form is used: ~shite-iru.

On the other hand, yasai ga ookiku naru hasn't occurred yet. So our objective is that this situation occurs eventually, and for that purpose we're doing something else currently.

Note that we have both naru and suru in the same sentence, so ookiku is a state for naru within a state for suru. Trying to rewrite this sentence to use only one state makes as little sense in Japanese as it would in English:

- #mai-nichi yasai wo {ookiku} mizu-yari shite-iru

毎日野菜を大きく水やりしている

#I'm watering the vegetables {big} every day.

Enforcing Habits

Sometimes, ~you ni ~ように is used with a causing verb in ~te-iru form to express that you have been doing or avoiding doing something regularly. For example:

- watashi wa tabako wo suwanai

私はタバコを吸わない

I don't breathe in tobacco. (literally.)

I don't smoke.- Here I say I don't have a habit of smoking. I'm not a smoker.

- watashi wa {{tabako wo suwanai} you ni} shite-iru

私はタバコを吸わないようにしている

I have been doing [something] causing {a way in which {[I] don't smoke cigars}}.

I've been trying to not smoke cigars.

I have decided to stop smoking, so I actively avoiding smoking now.

Above we have the scenario tabako wo suwanai, and shite-iru indicates that I'm keeping it that way. I'm doing something, or have been doing something, to ensure tabako wo suwanai remains true.

In practice, this tends to mean I just decided to start or stop doing something, and I'm abiding by that decision.

- mai-nichi hon wo yonde-iru

毎日本を読んでいる

[I] have been reading books every day.- This communicates what I've been doing.

- {{mai-nichi hon wo yomu} you ni} shite-iru

毎日本を読むようにしている

[I] have been making [myself] {{read books every day}}.- This communicates what I've been trying to achieve.

Note: because of how plurals work in Japanese, it's ambiguous whether the subject is reading only one single book or various different books every day.

A similar construction is ~koto ni suru ~ことにする, which is used when you decide to do one thing instead of another.

- {{hon wo yomu} koto ni} shita

本を読むことにした

[I] decided {{to read books}}.- I had the choice between reading a book and watching TV, and I decided book.

In essence, ~you ni suru is about the end result, while ~koto ni suru is about the decision.

- {{tabako wo suwanai} koto ni} shite-iru

タバコを吸わないことにしている

[I] have been choosing {{to not smoke}}.

[I] have chosen {{to not smoke}}.- This ~koto ni sentence means I just chose to not smoke, so it's perfectly valid even in a context where I never smoked before.

- The ~you ni version means the end result I'm laboring for is one where I don't smoke, this means that without my interference, the end result would be different, i.e. I would smoke, which in turn means I must be smoking currently and trying to stop myself from smoking in the future.

Note that any "effort" that can be understood here is merely implied. The verb only says a situation is being caused, and could have happened just as effortlessly as it could have been caused through lots of blood and tears. To be explicit, one might say:

- sou wa naranai

そうはならない

Things won't become the aforementioned way.

Things won't become like [you] said.

That won't happen. - {{sou naranai} you ni} doryoku shimasu

そうならないように努力します

{So that {that doesn't happen}}, [I] will work hard.

{So that {things don't turn the way you said}}, [I] will work hard.

- doryoku - hard-work, effort, and suru-verb for "working hard" or "putting effort" into doing something.

Prayer

The phrase ~you ni ~ように is sometimes found at the end of sentences when someone is praying for something or making a wish upon a star, or something of sort.

- {{okane-mochi ni} narimasu} you ni

お金持ちになりますように

[Let it be] so that {[I] become {rich}}.

I wish to become rich. - {{hayaku} naorimasu} you ni

早く治りますように

[Let it be] so that {[it] heals {quickly}}.

I wish to get well soon.

By the way, the word for this is:

- negai-goto

願い事

Wishes. A thing (koto こと) that you wish for (negau 願う).

This usage is peculiar in that what comes before ~you ni ~ように can be, and often is, in polite form. Normally, you wouldn't use the polite form before ~you ~様, but when making wishes, prayers, it can be used this way.

Right: Vignette Tsukinose April, 月乃瀬=ヴィネット=エイプリル

Manga: Gabriel DropOut, ガヴリールドロップアウト (Chapter 21)

- Context: Vignette, who is an angel, takes part in the Japanese custom of going to a Buddhist temple in the new year's eve, ringing a large bell, making a prayer wishing for something in the coming year (using ~you ni), then clapping twice. Satania, who is a demon, tags along, and while she foretells her ambitions coming true, she is a strong, independent demon who doesn't need no prayer to make them happen, so she doesn't use ~you ni.

- misoka 三十日 - the last day of the month. Although literally it means the "30th day."

- oo-misoka 大晦日 - the last day of the year, the new year's eve. Literally the "great" misoka, probably because it's the last of the last days.

- joya no kane 除夜の鐘 - the name of the bell they ring in the temples.

- garan garan

ガランガラン

*sound of the bell* - {minna ga kenkou de arimasu} you ni

みんなが健康でありますように

[Let it be that] {everyone be healthy}. (literally.)

- de aru である - "to exist [in a way]," "to be."

- pan pan

パンパン

*clap clap* - {dai-akuma ni} naru!!

大悪魔になる

[I] will become {a great demon}. - inoranai kedo

祈らないけど

[I] won't pray, though.

Sometimes ~you ni appears at the end of a sentence that isn't prayer, in which case the causing part was omitted, and it means "make sure that this happens."

- {{neru} mae ni ha wo migaku} you ni!

寝る前に歯を磨くように!

[Make sure that] {[you] brush your teeth before {sleeping}}!

(incomplete sentence.)- {{X} you ni} shite-kudasai

〇〇ようにしてください

Please make [it] {so [that] {X}}.

Please ensure that X.

- {{X} you ni} shite-kudasai

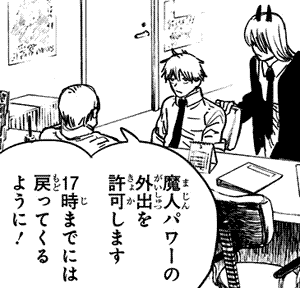

- Context: a demon under custody is allowed to go outside.

- majin Pawaa no gaishutsu wo kyoka shimasu

魔人パワーの外出を許可します

[I] permit the going-outside of the demon Power. (literally.)

[I] permit the demon Power to go outside. - {juu-shichi-ji made ni wa modotte-kuru} you ni!

17時までには戻ってくるように!

[Make sure] {to come back before seventeen hours}.

You must return before 5 PM.

- Here, the person permitting the leave warns the other characters they must keep in mind the following situation must happen: them "returning before 17 hours." If that doesn't happen, it's implied there will be trouble.

There's No Way To X

When ~you ~よう is suffixed to the ren'youkei of a verb in a negative sentence, it means there doesn't seem to be a way for something to happen, it seem impossible, unfeasible, inconceivable. For example:

- kachi-you ga nai

勝ちようがない

There's no way to win. - nige-you ga nai

逃げようがない

There's no way to escape.

The "there's no" part comes from nai 無い. Literally, it would mean "a seeming for winning/escaping to happen doesn't exist" or something like that. Thus technically you could say such seeming exists by using the affirmative aru ある, "to exist," "there is," instead, e.g.:

- kachi-you ga aru

勝ちようがある

There's a way to win.

In practice, however, it's pretty much always used negatively.

Also, beware that with some verbs it ends up looking identical to the volitional form:

- setsumei shiyou

説明しよう

Let's explain.

- shiyou - volitional form, also called u-kei ウ形, because it's shiyo~ plus ~u.

- setsumei shitakutemo shi-you ga nai

説明したくてもしようがない

Even if [I] wanted to explain, there's no way to.- shi-you - ren'youkei of suru plus ~you.

Furthermore, there's also this:

- shouganai

しょうがない

There's no helping it. It can't be helped.

There's nothing that we could have done about it.

Fine, since there's no other way, I'll do it.

There's no fixing it.

There's no fixing that person.

It has a small kana: sho しょ, not shiyo しよ, so it's a tiny bit different.

Regardless, shouganai actually comes from shiyou ga nai, that's why its meaning and spelling are so similar.

For suru, sometimes it's spelled shiyou 仕様. This same unusual way to spell happens in shikata 仕方, "way to do."

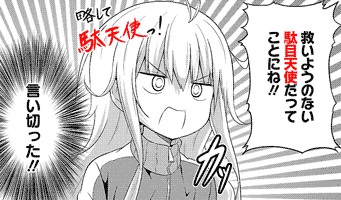

- Context: Tenma Gabriel White 天真=ガヴリール=ホワイト has realized what she really is.

- {sukui-you no nai} dame tenshi datte koto ni ne!!

救いようのない駄目天使だってことにね!!

A {[hopeless]} failure of an angel is [what I am]!- sukuu

救う

To save. - sukui-you no nai

救いようのない

No apparent way of saving.

Without a way to save [someone].

Futile to try to save. Hopeless. Gone for good.

- sukuu

- ryaku shite datenshi'!

略して駄天使っ!

Abbreviate it: failen angel!

(this is Crunchyroll's translation, which I must admit: was great.)

- datenshi

堕天使

Fallen angel. - daten suru

堕天する

To fall from heaven. (i.e. to lose one's holiness.) - ochiru

堕る

To fall. To drop. (in the sense of: to degenerate.) - The pun replaces the da of datenshi 堕天使 with da of dame 駄目, "useless," implying the angel isn't fallen become it's become evil, it's fail-en as it's become an useless failure who plays MMORPGs all day and has no future.

- datenshi

- ii-kitta!!

言い切った!!

[She] declared it!!

Uncertain Conclusions

The phrase you da ようだ is used instead of da だ to say you feel something is a certain way, but you aren't completely sure about it.(デジタル大辞泉:様だ)

The simplest way this is used is when trying to identify what something is. If you know for sure what it is, you might use da だ. But if the way it is looks like it would be something, it makes you think it would be something, but you don't know for sure, then you da ようだ is used. For example:

- neko da!

猫だ!

[It] is a cat!- I'm sure of it!

- neko no you da!

猫のようだ!

?[It] is a cat, I conclude!

[It] is a cat, I think!

[It] seems to be a cat!

[It] appears to be a cat!

- In English, nobody says "I conclude" this manner, though, although "I think" is often acceptable.

- neko no you desu

猫のようです

This would be like saying:

- neko da! tabun

猫だ!多分

[It] is a cat! Probably.

And the opposite of:

- neko ni chigainai!

猫に違いない!

There's no doubt: [it] is a cat!

This usage of changing "it IS a thing" to "it seems TO BE a thing" occurs when you have a copula such as da だ or desu です, but what comes before you 様 isn't necessarily a copula—you can have any random verb before it:

- kono kikai wa doko mo koushou shite-inai

この機械はどこも故障していない

This machine isn't broken anywhere. (literally.)

There isn't any part of this machine that is broken.- I'm sure of it.

- kono kikai wa {doko mo koushou shite-inai} you da

この機械はどこも故障していないようだ(デジタル大辞泉:様だ)

This machine seems {not to be broken anywhere}.

This machine {isn't broken anywhere}, I think.

Syntactically, we could say it works like this:

- Proposition in predicative form = certainty.

- Proposition in attributive form + ようだ = uncertainty.

For verbs both predicative and attributive forms are identical, so it's hard to see any difference, but with nouns like "cat," neko, the da だ predicative copula turns into a no の when it's attributive, giving them the name of no-adjectives, hence neko no you da 猫のようだ.

Similarly, with na-adjectives, it follows we would have the na な attributive copula before you da ようだ.

- kono basho wa kiken da

この場所は危険だ

This place is dangerous. - koko wa {kiken na} basho da

ここは危険な場所だ

This is place [that] {is dangerous}.

This is a {dangerous} place. - koko wa {kiken na} you da

ここは危険なようだ

This place seems {to be dangerous}.

However, in practice, it seems people also use ~no you da instead of ~na you da with na-adjectives, so so you probably can use ~no you da every time.

- koko wa {kiken no} you da

ここは危険のようだ

Despite ~you da translating to "seems," it doesn't need to be something optically visible. The phrase is merely a way to avoid claiming something with certainty, based on some evidence you got. It's sometimes called an "evidentiality marker" for this reason.

- Context: you touch someone's forehead.

- {netsu ga aru} you da

熱があるようだ

{[He] has ever}, I think.

It seems {[he] has fever}.- Here, you say there is evidence he has fever.

- Context: a doctor sees the results of a patient's exam.

- {gan dewanai} you desu

癌ではないようです

It seems {[it] isn't cancer}.

It doesn't seem to be cancer.- Here, the doctor is saying there is evidence the patient doesn't have cancer.

That's how it works, basically. You can have anything before ~you ~よう and it will make that uncertain.

You can have a habitual sentence, for example:

- Context: you visit a restaurant multiple times, and you notice that:

- {mein wa mai-nichi kawaru} you desu

メインは毎日変わるようです

It seems {the main [dish] changes every day}. - Context: in a game, an enemy monster can't be harmed by swords, only by magic.

- {butsuri-kougeki wa kikanai} you da

物理攻撃は効かないようだ

It seems {physical attacks don't work}. (in the sense of "have no effect.")

And even a condition:

- {{reizouko ni irenai} to kusaru} you da

冷蔵庫に入れないと腐るようだ

It seems {{if [you] don't put [it]} in the fridge, it will rot}.

{[It] rots {if [you] don't put [it] in the fridge}}, I think.

Past Tense Propositions

It's possible to conjugate either the proposition or ~you da ~ようだ to past tense. Each case has a different meaning.

When the proposition is in past tense, you would be saying it seems, that you feel currently, at the present, that something did occur at a past time:

- {neko datta} you da

猫だったようだ

It seems {[it] was a cat}.

Meanwhile when ~you da is conjugated to past tense, ~you datta ~ようだった, you would be saying that in the past you felt something is true. This would occur when narrating events in past tense.

- {neko no} you datta

猫のようだった

It seemed {[it] was a cat}.

Note that due to how tense works in Japanese, the present-tensed neko no translates to "it was a cat" in English, because in Japanese the tense of the subordinate is relative to its matrix, while in English it's relative to the time of utterance.

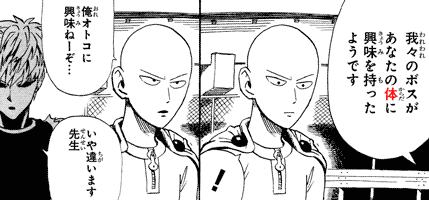

- Context: a caped baldy with extreme strength is targeted by an evil organization. He interrogates one the bad guys concerning why they're after him.

- {wareware no bosu ga anata no karada ni kyoumi wo motta} you desu

我々のボスがあなたの体に興味を持ったようです

It seems {our boss [got interested] in your body}.- ~ni kyoumi wo motte-iru

に興味を持っている

To have interest in.

To be interested in. - motsu - an eventive verb meaning "to get." Once something has been gotten (present perfect), it means "to have," motte-iru, consequently kyoumi wo motte-iru means "to have interest" in the present, while kyoumi wo motta 興味を持った (past perfective) refers to when "interest" was first gotten, the moment someone "became interested" in something.

- ~ni kyoumi wo motte-iru

- !

- ore, otoko ni kyoumi nee zo...

俺オトコに興味ねーぞ・・・

I don't have interest in men... - iya, chigaimasu, sensei

いや違います先生

No, [you got it wrong], master.- They aren't "interested" as in "attracted," they are "interested" in why he's so physically powerful.

Hearsay

It seems you 様 can be used with hearsay as well, even though, typically, it's said that with hearsay you use rashii らしい, not you 様. For example:(Karlsson, 2013:14–15, citing example from McCready & Nogata 2007b:189)

- {shinbun ni yoru to} {sensou ga hajimaru} you da

新聞によると戦争が始まるようだ

{According to the journal}, it seems {the war will begin}.

{According to the news}, {the war will begin}, I think.

- The romaji used in the source was: shinbun ni yoru to sensoo ga hajimaru yooda.

This needs a bit of explanation.

First off, "hearsay" here refers to information you heard from someone else. Above we have "according to the journal" so that's obvious, but with rashii we could have something like:

- sensou ga hajimaru rashii

戦争が始まるらしい.

[They say] the war will start.

What rashii means is essentially "I don't know for sure, but that's what I heard." People are saying this, so maybe it's true. Maybe they're liars. Who knows. Just floating the idea there, for reference.

But if you hear something from somewhere, that's information you can consider and come to a conclusion about yourself.

For example: based on the fact it's on the news, I conclude it must be true.

After Pronouns

The word you 様 can be qualified by demonstrative and interrogative pronouns "this," "that," and "what." Beware that in Japanese we have two different sets:

- kore, sore, are, dore これ, それ, あれ, どれ

Pro-NOUNS, e.g. "this thing," "that thing." - kono, sono, ano, dono この, その, あの, どの

Pro-ADJECTIVES, e.g. "this [whatever comes after]."

Typically the pro-noun kore is used with the conclusion ~you, while the pro-adjective kono is used with the likeness ~you. Observe:

- kore no you da

これのようだ

It seems [it] is this thing.

- What's the thing we're supposed to get from here?

- *points to a thing* it seems it's this thing!

- kono you ni

このように

Like this.- How are we going to get this thing through the door?

- *rotates it sideways* like this!

Some examples:

- Context: an article contains the image of a cross-section of a key inserted in a lock, showing the pins in the lock being displaced by the key, with the following paragraph below.[kagisapo24.com:自分で鍵をつくる, accessed 2022-07-24.]

- kono you ni, kagi no gizagiza wa {{kagi-ana no pin no takasa wo chousei suru} tame ni} aru no desu

このように、鍵のギザギザは鍵穴のピンの高さを調整するためにあるのです

Like this (i.e. the way shown in the picture above), the ridges of the key exist {with the purpose {to adjust the height of the pins in the keyhole}}.- When the key is the right one, its ridges are shaped in such way that when inserted in a keyhole the pins are lifted high enough for the lock to unlock.

- gizagiza - mimetic word for zig-zag-like indented parts, ridges.

- {sono you na} koto wa ariemasen!

そのようなことはありえません!

Something {like that} can't exist! (literally.)

Something {like that} is inconceivable!

There's no way something like that happened!- ~koto ga aru - for something "to exist" in the sense that it occurs. Is this a thing that happens?

- ari-eru - to be able to happen, a potential form for aru ある.

- Here, sono means "that" in the sense of something aforementioned, e.g. someone says something is going to happen, and the next person responds like this.

- {dono you na} goyouken deshou ka?

どのようなご用件でしょうか?

What sort of business [do you have to discuss]?- The de-relativization would be:

- goyouken wa dono you da?

ご用件はどのようだ?

The business [you have with me] is like what? (literally.) - The dono works in the sense of "the business is like SOMETHING, but I don't know WHAT."

- Since we don't talk like this in English, it more naturally translates to "what sort of" business.

Besides these, there are also pronouns, like itsu いつ, which may also be used with ~you:

- sore wa itsu mo no you da

それはいつものようだ

That is like always.

That is always, I think.- itsu - "when."

- itsu mo - "always," "whenever."

- {itsu mo no you ni} waratte-iru

いつものように笑っている

[He] is laughing {like always}.

He's smiling {like he always does}. - Context: someone buys a mat, it comes with cost of shipping included.[plaza.rakuten.co.jp/naomugi:おしゃれでシックな玄関マット, accessed 2022-07-25.]

- souryou-komi wa tamatama dewanakute, itsu mo no you desu

送料込みはたまたまではなくて、いつものようです

The cost of shipping being included isn't ocasional, it's always, I think. (literally.)

It seems the cost of shipping being included isn't something that happens occasionally, it always happens.- i.e. it's included regardless of the product you buy from that store, rather than it being just this product.

vs. ~んな

Phrases combining pro-adjectives with ~you na, ending in ~no you na ~のような, are similar the pro-adjectives ending in ~nna ~んな, konna, sonna, anna, donna こんな, そんな, あんな, どんな.

| kono you na このような |

konna こんな |

|---|---|

| sono you na そのような |

sonna そんな |

| ano you na あのような |

anna あんな |

| dono you na どのような |

donna どんな |

When they are interchangeable, kono you na, for example, would be a more formal way to say a thing, while konna would be a more casual way.

- donna riyuu demo bouryoku wa dame

どんな理由でも暴力はダメ

No matter what sort of reason [you got], violence is not okay. - dono you na riyuu ga arou to mo {bouryoku wo furuu} koto wa {zettai ni} yurusaremasen

どのような理由があろうとも暴力を振るうことは絶対に許されません

No matter what sort of reason [one] may have, the {wielding of violence} {absolutely} can not be permitted.

There are cases where they aren't interchangeable. This occurs because konna can come before no の and ni に to form konna no こんなの and konna ni こんなに, but there are cases these phrases don't have an equivalent kono you~ phrase.

- konna ni takusan!

こんなに沢山!

[Wow, there are] so many! - konna no shinjirarenai

こんなの信じられない

[I] can't believe something like this.

No comments: