In Japanese, ~i ~い is a suffix that functions like a copula, which is found in i-adjectives, giving them their name. For example: kawaii かわいい doesn't mean just "cute," it means "to be cute," and we can separate the morphemes into the stem kawai~ meaning "cute," and ~i meaning "to be." This ~i ~い is sometimes suffixed to random stuff to create new adjectives, and, in rare cases, used adverbially:

- tekui

テクい

Skilled. (as in having "technique," tekunikku テクニック) - erai muzukashii

偉い難しい

Extremely difficult.

Grammar

See the article about i-adjectives for conjugation and other grammar about the words that end in ~i. This article is mainly about the suffix itself.

Copula

The ~i suffix found in i-adjectives has a function analogous to the da だ copula, na な copula, and no の copula used with na-adjectives and no-adjectives (nouns). Since the latter are copulas, it follows that ~i, too, is a copula. Compare:

| shuushikei 終止形 | rentaikei 連体形 | |

|---|---|---|

| i-adjective | Tarou ga wakai 太郎が若い Tarou is young. |

{wakai} hito 若い人 A person [that] {is young}. A {young} person. |

| na-adjective | kuni ga heiwa da 国が平和だ The country is peaceful. |

{heiwa na} kuni 平和な国 A country [that] {is peaceful}. A {peaceful} country. |

| no-adjective | neko ga doubutsu da 猫が動物だ A cat is an animal. |

{doubutsu no} neko 動物の猫 The cat, [which] {is an animal}. The {animal} cat. |

An example:

- Context: motion lines everywhere, I can't see a thing!

- hayai!

速い!

[He] is fast!

The only difference between the copulative suffix ~i ~い and the da だ copula is that da だ can often be omitted, i.e. replaced by a null copula, so it's easier to consider da だ as being separate, while ~i is considered part of the i-adjective word: it's sometimes omitted in exclamations, but that's nonstandard.

- kuni ga heiwa φ

国が平和

The country [is] peaceful.- φ - null copula.

- kowa!

こわ!

Scary!- This would be kowai 怖い with the ~i suffix clipped. Similarly: sugo, yaba, uma, samu would be clippings of sugoi すごい, "it's incredible," yabai やばい, "it's terrible (oh no!)," umai うまい, "it's delicious," samui 寒い, "it's cold."

Anime: Zombieland Saga: Revenge (Episode 6)

- Context: a random social media user comments on the legendary Yamada Tae, who is also known by the pseudonym "number 0," zero-gou 0号.

- zero-gou kami-kawa!!!!!!!

0号神かわ!!!!!!!

Number 0 is super cute!!!!!!!

In dictionaries, too, the dictionary form of an i-adjective includes the ~i copula, while of a na-adjective doesn't include the da copula.

As one would expect, if ~i functions as a copula, and da functions as a copula, you don't say ~i da ~いだ, because the function of da だ is already performed by ~i ~い.

- *kowai da

怖いだ

*It is is scary. (wrong.)- This is allowed metalinguistically, e.g. someone asks if a word written somewhere is supposed to be kowai or kawai, you answer:

- "kowaI" da

「怖い」だ

It is "kowai."

In polite speech (teineigo 丁寧語), da だ is generally replaced by desu です. There's no polite copula counterpart for ~i ~い. Instead, desu です is added after ~i. The phrase ~i desu ~いです is allowed even though ~i da ~いだ is not because desu also has the polite function that ~i doesn't have, so it's not redundant.

- kowai desu

怖いです

It is scary. (polite speech.)

I'm scared.

Note that i-adjectives that refer to mental states, among others, have translations that are difficult to understand in English as a copula due to double subject constructions found in Japanese. Observe:

- watashi wa {kumo ga kowai}

私は蜘蛛が怖い

{Scary is true about spiders} is true about me.

{Spiders are scary} is true about me. (here, ~i directly translates to the copula "are.")

I'm scared of spiders. (here, ~i no longer directly translates, despite the copula "am.")

- kumo - small subject predicated by kowai.

- watashi - large subject (and topic) predicated by kumo ga kowai.

Contractions

There are common contractions that affect the ~i copula, merging it with the preceding syllable to form a long vowel, typically changing the ending to a small ~e ~ぇ or ~i ~ぃ (small kana).

- ~aい to ~eぇ

- ~oい to ~eぇ

- tsuyoi 強い to tsuee 強ぇ, "strong."

- kakkoii かっこいい to kakkee かっけぇ, "cool."

- ~uい to ~iぃ

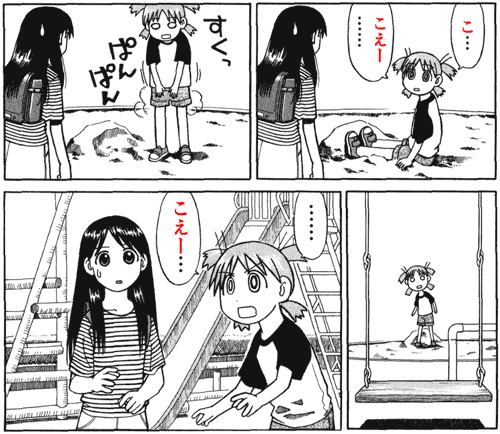

- koee

こえー

- kowai

怖い

Scary.

- kowai

Adverbial Usage

In rare cases, the ~i copula is used like an adverb, analogous to the ni に adverbial copula, a.k.a. the ren'youkei 連用形 of da だ. Normally, ~ku ~く would be the ren'youkei of ~i, but with extremely few intensifying words, like sugoi すごい, "incredible," you have what's called a flat adverb, where an adjective is used in its adjectival form, rather than its adverbial form, to express its adverbial meaning.

See flat adverbs for details.

Anime: Uzaki-chan wa Asobitai! 宇崎ちゃんは遊びたい! (Episode 1)

Neologisms

The ~i copula is sometimes attached to stuff to create new adjectives. In particular, new i-adjectives, slangs, created out of gairaigo 外来語 loan words are prone end up being spelled in a mixture of katakana カタカナ for the non-Japanese part, and hiragana ひらがな for the native ~i suffix. For example:

- hidoi

酷い

Horrible. Cruel. From hidou 非道, "inhuman." - shindoi

しんどい

Tiresome. From shinrou 辛労, "hardship." - shikakui

四角い

Quadrilateral (i.e. rectangular). From shikaku 四角, "quadrilateral (i.e. rectangle)." - kiiroi

黄色い

Yellow (adjective). From ki-iro 黄色, "yellow (noun)." - gesui

ゲスい

Scummy. Sleazy. From gesu 下種, literally "lower sort," as in a "low-life." See also: gesugao ゲス顔. - emoi

エモい

From "emotional," katakanized emooshonaru エモーショナル.

Used when referring to emotional, deep, heavy stories, scenes, or when one's feeling emotional, etc. - eroi

エロい

Sexy. Hot. From "erotic," erochikku エロチック. - guroi

グロい

From "grotesque," gurotesuku グロテスク. More specifically, from the term guro グロ, which refers to body horror (gore, death).

Used to say a series is gore-ly, or to refer to a body part as being grotesque (e.g. disfigured). - naui

ナウい

New. Trendy. From "now," nau ナウ.

(apparently a slang from the 80's that nobody uses nowadays but still survives in media when making references to the 80's.) - jerashii

ジェラしい

Jealous. Envious. From "jealously," jerashii ジェラシー. - tekui

テクい

Skilled (in a game, sport). From "technique," tekunikku テクニック. - puroi

プロい

Pro-like. Pro-level. From "pro"," puro プロ.

Abbreviations

Some i-adjectives that mix katakana and hiragana are abbreviations of other i-adjectives:

- kimoi

キモい

Gross. From kimochi-warui 気持ち悪い. - uzai

ウザい

Annoying. From uzattai うざったい - panai

パナい

Serious. From hanpa nai 半端ない, "not half-hearted."

Etymology

The ~i ~い copula originates in a ~ki ~き suffix undergoing consonant deletion (or i-onbin イ音便), e.g. you had the word wakaki 若き and the ~k~ consonant was removed (or ki replaced by i), so you ended up with wakai 若い, "young." The ~ki was replaced by ~i (i.e. ~i became more commonly used) after the 13th century, in the early "Kamakura Period," Kamakura-jidai 鎌倉時代.(坪井, 1997:1, citing 桜井, 1966a, b; Fujiyoshi, 1982:88)

This ~ki ~き suffix was the rentaikei 連体形 of adjectives, while a ~shi ~し suffix was the shuushikei 終止形 in what's called "ku conjugation," ku-katsuyou ク活用.

One cool example is yoi よい, "good," which used to be yoki よき and yoshi よし a thousand years ago. You can find still find yoki in dialogues where characters speak archaically, meanwhile yoshi survived as an interjection for "alright" in modern Japanese.

Besides this, there was also a "shiku conjugation," shiku-katsuyou シク活用, which was very similar to ku-conjugation, but while the rentaikei was ~shiki ~しき, the shuushikei was just ~shi ~し, e.g.: the modern utsukushii 美しい, "beautiful," was utsukushiki 美しき and utsukushi 美し. The modern utsukushii has a long vowel (shii しー), while the old one had just a short vowel. Same applies to similar words: kanashii 悲しい, "sad," osoroshii 恐ろしい, "terrifying," and so on.

The terms ku and shiku conjugation come from their ren'youkei 連用形, by the way (e.g. yoku よく, utsukushiku 美しく), which remain the same in modern Japanese.

In modern Japanese, ~i is used for both shuushikei and rentaikei, and both ku conjugation and shiku conjugation were replaced by ~i. Basically the ~ku ending they shared in the ren'youkei started getting replaced by ~i to make their shuushikei and rentaikei. The popularization of ~i started with the rentaikei, and in the "Muromachi Period," Muromachi-jidai 室町時代 (1336–1573), the shuushikei also started ending with ~i, until everything became the uniform conjugation we have today.(坪井, 1997:42, citing 山崎, 1992)

If you see a character using the non-i-ending, ku-and-shiku-conjugations, that could be a hint they're from a period of time before the popularization of ~i, but like yoshi, there are some phrases that have survived containing the old conjugations somehow. The old conjugations can also be used for the poetic factor, because they're so classical-sounding, e.g. in titles and lyrics of songs and so on.

- Context: Kongming 孔明, a 3rd century Chinese strategist, sees a mirror for the first time after being reincarnated in the modern world.

- kore wa.... {wakaki} hi no waga sugata....

これは・・・・若き日の我が姿・・・・

This... is my appearance from the days [when] {[I] was young}.

- "was" - the tense of a relative clause may be relative its matrix.

- {ikanaru} genjutsu deshou ka?

いかなる幻術でしょうか?

{What sort of} illusion is this?

{What sort of} witchcraft is this?

Homonyms

Not everything that ends in ~i has the ~i copula. For reference, some examples of homonyms, starting with words that merely end with an ~i ~い syllable:

- hai

はい

Yes. (used to agree with whatever the other person said.)

No. (e.g. "tomatoes aren't fruits, right?" hai = "no.")

Most words are spelled with kanji, while ~i copula is written with hiragana, so it's generally impossible to mistake the ~i copula for an i い syllable, except for words that are sometimes spelled with hiragana for some reason.

- kirei

きれい

Beautiful. Pretty.- Is this an i-adjective?

- kirei

綺麗

- Nope. It's a na-adjective.

Ren'youkei of Godan Verbs

The ren'youkei of godan verbs ending in ~u ends in ~i.

- chigai

違い

Difference. - kai-mono 買い物, "purchased goods," from kau 買う, "to purchase."

- nanno mayoi mo naku なんの迷いもなく, "without any hesitation," from mayou 迷う, "to hesitate."

The ren'youkei of godan verbs ending in ~ru ends in ~ri, but this ending sometimes undergoes i-onbin イ音便, changing it to ~i ~い.

- irassharu

いらっしゃる

To be. To come. To go. (sonkeigo 尊敬語 variant of iru いる, kuru 来る, iku 行く.) - *irasshari-masu

いらっしゃります - irasshaimasu

いらっしゃいます - irasshaimase

いらっしゃいませ

Welcome. (expression used when someone arrives at a store.) - irasshai

いらっしゃい - tabenasai

食べなさい

Eat [it]. (imperative sentence.)- ~nasai ~なさい comes from nasaru なさる by the same process irasshai comes from irassharu.

Adjective-Like Conjugation of Godan Verbs

Humorously, the godan verb chigau 違う has been being erroneously conjugated as an i-adjective by youngsters(石井, 2011:1), which means people saw its ren'youkei chigai and thought it worked so much like an adjective they just turned the word into one.

- chigakute

違くて

[That's not it].- The te-form of chigau would be chigatte 違って, but chigatte wouldn't be used the same way as chigakute.

Particle

There's an i い particle found at sentence-ending position that's often used to soften the tone of sentences, e.g. sou ka i そうかい, "is that so," nanda i なんだい, "what is it," iku zo i 行くぞい, "let's go," and so on.

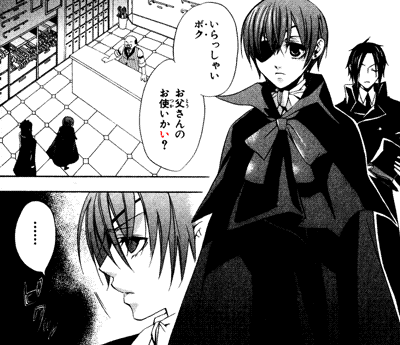

- Context: Ciel Phantomhive シエル・ファントムハイヴ, a 12 year old boy whose first person pronoun is boku 僕, gets annoyed when called boku, meaning "boy," by a shopkeeper, mostly because his parents died, he decided to become the head of the Phantomhive family, and as such he doesn't want to be treated like a kid.

- irasshai boku, otousan no otsukai ka i?

いらっしゃいボク お父さんのお使いかい?

Welcome, boy, is [it] [your] father's errand? (literally.)- Are you here doing an errand for your father?

- bouten 傍点 - the dots on the furigana besides the word boku ボク, used to indicate emphasis, like bold text in English. In this case, the emphasis is due to Ciel taking offense on the word boku specifically.

- piku'

ピクッ

*twitch* (with irritation, in this case.)

Do your three sources mention "Copula"? Because people online seem to disagree with the idea of the i suffix being anything close to a copula or even copulative. I burn for an answer, I would love to hear from you.

ReplyDeleteHello. Whether you classify it as a copula or not isn't very important, so sources that classify ~i as a copula generally won't claim "it is a copula" literally. Instead, they'll just use "COP" (for copula) to label the morpheme's function in analysis, e.g.

Deleteutsukushi.i becomes beautiful.COP because ~i stands for COPula and the stem utsukushi~ stands for "beautiful." Similarly, kirei da would become pretty.COP.

Considering ~i, no, na, da, ~ku, ~ni, etc., have analogous functions in modern Japanese, I don't think it would make sense to claim da is a copula without claiming ~i is also a copula, so I just labelled them all as copulas.

This could sound weird if you are under the impression that there is only one copula per language or something of sort, which isn't really the case. For instance, you could say "continues" is a copula in English, since "the water continues frozen" has the same syntax structure as "the water is frozen" with frozen being the subject complement and the verb is/continues linking it to the subject water. Similarly, seems, becomes, remains, smells, sounds, etc. could all be considered copulas depending on whom you ask.

For reference, Masaharu Shimada in Apparent Omission of Inflectional Endings in Japanese Adjectives writes "What is going on in -i dropped adjectives? How can the copula -i be omitted and when?" in reference to the sentence このビルは高! where the い was omitted from 高い.

Hello Leo, thank you for your answer. May I ask where you found "Masaharu Shimada in Apparent Omission of Inflectional Endings in Japanese Adjectives"? My internet searches have not been very rewarding.

ReplyDeleteI found a list of his research here at researchmap.jp, however, none of the publications is the one in question.

Anyways, I found this thesis here:

https://linguistics.stonybrook.edu/_pdf/dissertation/Yamakido_2005_dissertation.pdf

In it, the author argues that -i, -ku, -na, -ni and such are case-markers, not copula.

He lists some very interesting points about -ku as well which might interest you.

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Fuzhen-Si-2/publication/340022794_2017-Si_Fuzhen-Studies_on_Syntactic_Cartography-full_text/links/5e7323f4299bf1571848c5f1/2017-Si-Fuzhen-Studies-on-Syntactic-Cartography-full-text.pdf#page=378

DeleteTheir paper starts at page 371.

From the paper you linked, page 43, it reads:

Notice that the morphemes occurring in (3a) (and (1)) also appear in (5). Similarly, the marker –na occurring in (3b) (and (2)) is quite similar to the da appearing in (6). In predicative TA examples, Japanese –i is standardly analyzed either as a present tense marker, or as a present tense form of the copula. Similarly in predicative NAs, da is typically analyzed as an inflected copula. If these analyses are correct, then adjectives in prenominal position are nearly identical in morphology to sentential constructions; specifically, they look like sentential modifiers of the noun.

Given these points, it is tempting to propose that Japanese prenominal adjectives are

in fact just copular relative clauses, with the –i and –na elements having the status of copulas, as shown in (7). Indeed a number of researchers have proposed just this.

3 On this proposal, the structure of the modified nominal in (3a) is as in (8a), and not as in (8b). Furthermore, the correct semantics for the prenominal adjective construction is as in (9a), where A occurs as the predicate in a relative clause, and not as in (9b):

Note the part that says "Japanese –i is standardly analyzed [...] as a present tense form of the copula" in TA (True Adjectives, which is what the paper calls i-adjectives).

So at least it's not just me who claims this.

Personally, I call these morphemes copulas because when you consider their similarities it makes sense to put them all in a single group and the only group that makes sense are copulas. I think anyone learning Japanese would benefit from this categorization as well.

Please allow me one last comment.

ReplyDeleteI appreciate this unpopular and by many learners dismissed point of view because it brings clarity.

I sent you the paper because I wanted to share with you a viewpoint that differs from yours. Therefore I am thankful for your share of knowledge and linking of the paper you talked about, and your time.