In Japanese, a "suru verb," or "する verb," suru doushi スル動詞, refers to when a noun (called the verbal noun) becomes a verb by attaching the auxiliary verb suru する to it. For example:

- kekkon

結婚

Marriage.- This is a verbal noun.

- kekkon suru

結婚する

To do "a marriage."

To marry.- This is a suru verb.

The terms sa-hen doushi サ変動詞 (abbreviated sa-hen サ変), and sa-gyou henkaku katsuyou サ行変格活用, "irregular sa-row conjugation," typically refer to suru verbs (exceptions exist, like ohasu おはす, which is also considered sa-hen).

This article will talk about these, and other verbal noun + suru usage, such as (noun in bold):

- nani shiteru?

何してる?

What are [you] doing? - kakure mo nige mo shinai

隠れも逃げもしない

[I won't] hide or run away. - sore wa zettai ni shimasen

それは絶対にしません

[I] absolutely won't do that. - sonna koto shite wa ikenai

そんなことしてはいけない

[You] shouldn't do something like that. - shitenai yo

してないよ

[I] haven't done [it].

Conjugation

The conjugation of a suru-verb is mostly the conjugation of the auxiliary verb suru する that attaches to it, due to the simple fact that you can't conjugate nouns, so the noun part of a suru-verb can't change, only the suru part can change. Observe:

| Form | Conjugation |

|---|---|

| mizenkei 未然形 |

kekkon sa~ 結婚さ~ (e.g. ~seru ~せる.) |

| kekkon shi~ 結婚し~ (e.g. ~nai ~ない.) |

|

| kekkon se~ 結婚せ~ (e.g. ~nu ~ぬ.) |

|

| ren'youkei 連用形 |

kekkon shi~ 結婚し~ (e.g. ~masu ~ます.) |

| shuushikei 終止形 |

kekkon suru 結婚する |

| rentaikei 連体形 |

|

| kateikei 仮定形 |

kekkon sure~ 結婚すれ~ (e.g. ~ba ~ば.) |

| meireikei 命令形 |

kekkon shiro 結婚しろ |

| kekkon seyo 結婚せよ |

Above, no matter the form, the verbal noun kekkon stays unchanged, only suru changes. The same applies to tensed forms:

| Tensed form | Plain form | Polite form |

|---|---|---|

| hikakokei 非過去形 Nonpast form |

kekkon suru 結婚する Marries. Will marry. |

kekkon shimasu 結婚します |

| kakokei 過去形 Past form |

kekkon shita 結婚した Married. |

kekkon shimashita 結婚しました |

| hiteikei 否定形 Negative form |

kekkon shinai 結婚しない Doesn't marry. |

kekkon shimasen 結婚しません |

| kako-hiteikei 過去否定形 Past negative form |

kekkon shinakatta 結婚しなかった Didn't marry. |

kekkon shimasen deshita 結婚しませんでした |

| kanoukei 可能形 Potential form. |

kekkon dekiru* 結婚できる To be able to marry. |

kekkon dekimasu 結婚できます |

| ukemikei 受身形 Passive form. |

kekkon sareru 結婚させる To be married**. |

kekkon saremasu 結婚されます |

| shiekikei 使役形 Causative form. |

kekkon saseru 結婚させる To make [someone] marry. To force [someone] to marry. To allow [someone] to marry. |

kekkon sasemasu 結婚させます |

| ~te-iru form. | kekkon shite-iru 結婚している To be married**. To have married***. |

kekkon shite-imasu 結婚しています |

| kekkon shiteru 結婚してる |

kekkon shitemasu 結婚してます |

|

| ~te-aru form. | kekkon shite-aru 結婚してある To have married***. |

kekkon shite-arimasu 結婚してあります |

| ~te-shimau form. | kekkon shite-shimau 結婚してしまう To end up married****. |

kekkon shite-shimaimasu 結婚してしまいます |

| kekkon shicchau 結婚しっちゃう |

kekkon shicchaimasu 結婚しっちゃいます |

Note:

- The potential form of suru is irregular: instead of becoming sareru, as one could expect, it gets replaced by the verb dekiru できる.

- This "to be married" is in passive voice, e.g. "I was married at young age," in the sense of being married BY someone else (the agent of the passive). It isn't the same thing as "I'm married" as opposed to "I'm single."

- To be married in the sense of to have married is kekkon shite-iru 結婚している. Normally, in this case, however, to say someone is "already married" you'd use the word kikon 既婚, as opposed to mikon 未婚, "not yet married."

- The usage of ~te-aru is very limited and unlikely to occur with most verbs. It can be used if something has already been done in advance for something else, e.g. youi shite-aru 用意してある, "[I] have prepared [it]." With kekkon, that's unlikely to be the case.

- Generally in the sense that it's something you don't want to happen.

In verb groups categorization, suru-verbs are considered "group 3 verbs," san-guruupu doushi IIIグループ動詞, due to suru being irregular.

Other practical forms:

| Form | Conjugation |

|---|---|

| tai-form | kekkon shitai 結婚したい [I] want to marry. |

| ba-form | kekkon sureba 結婚すれば If [I] married. |

| kekkon surya 結婚すりゃ |

|

| tara-form | kekkon shitara 結婚したら If [I] married. |

| Volitional form. | kekkon shiyou 結婚しよう Let's marry. |

| nu-form. | kekkon senu 結婚せぬ To not marry. |

| kekkon sen 結婚せん |

|

| zu-form | kekkon sezu 結婚せず Without marrying. |

As you can see above, the verbal noun kekkon never changes, so you only need to know the conjugation of the verb suru, and then you know how to conjugate every suru-verb. All you need to do is to replace kekkon by another verbal noun, for example:

- seikou shita

成功した

[It] succeeded. - rikai dekinai

理解できない

[I] can't comprehend [it].- rikai - comprehension (verbal noun.)

- dekinai - can't (auxiliary verb).

- c.f.:

- ningen no rikai wo koeru

人間の理解を超える

To surpass human comprehension.

To be beyond human comprehension.

There are only a few cases where the conjugation of suru-verbs differ from non-suru verbs.

Infinitive Translation

In interactive user interfaces, labels of commands, buttons, that perform actions have their non-suru verbs in nonpast form, while suru-verbs can have the suru auxiliary stripped. In English, the infinitive form is used in these cases instead.

For example, the phrase "add to cart" used in the purchase button of online shopping websites becomes kaato ni ireru カートに入れる, "put in cart," while the "search" button becomes just kensaku 検索, instead of kensaku suru 検索する.

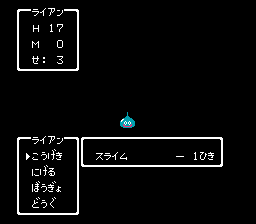

- Context: the battle screen against a slime, katakanized スライム, of a RPG with a list of possible commands for the player to choose.

- hiki ひき is the counter for small animals, creatures.

- ippiki 一匹 (spelled 1ひき here) means "one small animal," one slime in this case.

- Aian

アイアン - kougeki

攻撃

Attack.- A verbal noun: kougeki suru 攻撃する, "to attack."

- nigeru

逃げる

Escape.- An ichidan verb: nigeru 逃げる, "to escape."

- bougyo

防御

Defend.- A verbal noun: bougyo suru 防御する, "to defend."

- dougu

道具

Items.- A noun that's not verbal. It means literally "tools," but includes items like yakusou 薬草, "healing herbs."

Dictionary Form

In dictionaries, the form of a word as listed is called "dictionary form," jishokei 辞書形, which, for other verbs, is identical to the shuushikei and nonpast form, but with suru-verbs, the dictionary form is just the verbal noun, instead of the vebal noun plus suru.

This means, for example, that the verb kaku 書く, "to write," is listed in a dictionary as kaku 書く, but kekkon suru 結婚する will be listed as just the verbal noun kekkon 結婚, rather than kekkon suru.

In which case, a note somewhere will say the noun works as a suru-verb, e.g. by writing suru スル in katakana カタカナ somewhere.

The same occurs with na-adjectives: rather than including the na な attributive copula in their dictionary form, only the stem is written, e.g. kirei 綺麗 instead of kirei na 綺麗な, "[which] is pretty."

Noun Form

When referring to the process or outcome of an action, the noun form of a verb is used, which for non-suru verbs is their ren'youkei. With suru-verbs, you already have a noun that you're making into a verb, so instead of conjugating the suru to its ren'youkei, you just remove it. Observe:

- Tarou ga odoru

太郎が踊る

Tarou dances. - Tarou no odori wo mita

太郎の踊りを見た

[I] saw the dance of Tarou.

[I] saw the dance that Tarou did. - Tarou ga kokuhaku suru

太郎が告白する

Tarou confesses. - *Tarou no kokuhaku shi wo mita

太郎の告白しを見た - Tarou no kokuhaku wo mita

太郎の告白を見た

[I] saw the confession of Tarou.

[I] saw the confession that Tarou did.

Above, we can't conjugate suru to shi the same way we conjugated odoru to odori, even though they're both their respective verbs' ren'youkei.

This only applies to cases like the above. The ren'youkei is also used in other ways, so you may see the shi conjugation sometimes. For example, when the ni に particle marks the purpose:

- {odori} ni iku

踊りに行く

To go {dance}. - kokuhaku ni iku

告白に行く

To go to a confession. (destination ni に marking noun.) - {kokuhaku shi} ni iku

告白しに行く

To go {confess}. (purpose ni に marking verbal phrase.)- c.f.:

- ie ni {kokuhaku shi} ni iku

家に告白しに行く

To go to [their] house {confess}. - Above we can see the there are two ni に, each with a different function: one marks the destination, the other the purpose.

サ行変格活用

The irregular conjugation of the verb suru is called sa-gyou henkaku katsuyou サ行変格活用, "irregular sa-row conjugation."

In modern Japanese, only suru is conjugated like this, so this term, its abbreviation, sa-hen サ変, and "sa-hen verb," sa-hen doushi サ変動詞, will refer to the conjugation of suru when found in dictionaries and the sort.

In classic Japanese (kobun 古文), you'll have words like ohasu 御座す, a sonkeigo 尊敬語 synonym for aru ある, which also uses a sa-hen conjugation. This classical conjugation is a bit different from that of suru-verbs. It looks like this(学研全訳古語辞典: 御座す)

| Form | Conjugation |

|---|---|

| mizenkei 未然形 |

sa~ さ~ |

| ren'youkei 連用形 |

shi~ し~ |

| shuushikei 終止形 |

su す |

| rentaikei 連体形 |

suru する |

| izenkei 已然形 |

sure~ すれ~ |

| meireikei 命令形 |

seyo せよ |

First, note that ohasu is ohasuru in its rentaikei. In modern Japanese, the shuushikei and rentaikei of verbs is identical, which is why suru is suru in both.

This explains why it's called irregular "sa-row" conjugation, by the way. This "row" is in reference to godan conjugation. A sa-row godan verb, or a godan verb ending in ~su, is one like taosu 倒す, "to defeat," korosu 殺す, "to kill," and so on.

- There's also ka-row irregular conjugation: the verb kuru くる.

Regularly, their ba-form conjugations would be taoseba 倒せば, koroseba 殺せば, and so on. Meanwhile, ohasu is irregular, and doesn't become ohaseba, instead becoming ohasureba おはすれば.

Just like ~sureba was the ba-form of sa-hen verbs in classical Japanese, sureba is the ba-form of suru-verbs in modern Japanese.

One difference is that classical sa-hen verbs aren't composed of verbal nouns plus ~suru like suru-verbs, so you wouldn't be able to remove the ~suru or ~su suffix to get a noun or to use it like an English infinitive.

Bound Morphemes + ~する

This article is mainly about words that can be used as nouns by themselves and become verbs when you attach ~suru to them. A similar sort of word also ends in ~suru and is conjugated almost identically, but can't be split into noun and ~suru, i.e. you can't use the non-suru part by itself. For example:

- teki-suru

適する

To be appropriate for. To fit. To suit.

Above we have teki~ 適~, which is a bound morpheme, meaning that we can't split it from the word teki-suru and say just teki to mean something because teki~ isn't a word by itself—the teki~ morpheme must always be part of another word.

- teki-setsu

適切

Appropriate. - teki-nin

滴人

Appropriate person. The right person for a job. - teki-sei

適正

Aptitude. How appropriate something is.

We see from other words teki is part of that the meaning of teki has to do with being appropriate, but we can't use teki alone to say "appropriate."

- Not to be confused with the homonym teki 敵, which means "enemy" instead and can be used by itself.

The conjugation of such words is identical to the suru verbs of this article, with two exceptions stemming from the fact you can't remove ~suru from them:

- The dictionary form of teki-suru 適する is teki-suru 適する, with suru included.

- The noun form of teki-suru 適する is teki-shi 適し, its ren'youkei.

Such words are often said to be only one kanji long, which contrasts with the typical suru verb being a nouns spelled with two kanji followed by suru.

In Japanese, and probably Chinese as well, one kanji often (but not always) represents one morpheme, so it might be more accurate to say that such words only have one morpheme before the suru morpheme, and that's why they can't be separated.

The language prefers words composed of two kanji-morphemes, the first acting as a qualifier for the second, e.g. teki-nin is a person (nin) who is appropriate (teki), so teki qualifies nin, a person that is teki. Similarly, teki-suru ends up being "a verb that is teki" or something of sort.

If ALL words were two morphemes long, like teki-nin and teki-suru, you couldn't divide the parts to use them as single-morpheme words even though each part has its own separate meaning. This isn't strictly the case, however.

Japanese has some words that are one-morpheme long, and sometimes they get ~suru attached to them, so although one-kanji-morpheme-suru-ending-words are generally indivisible, there are always exceptions.

- ai

愛

Love. (a standalone word.) - ai suru

愛する

To love [someone]. (e.g. your children, the love of your life, humanity, etc.)

Pronunciation Changes

Words composed of a single morpheme plus suru often feature a change in pronunciation at morpheme boundary.

~っする

A ~ssuru ~っする ending is a word ending in ~suru affected by sokuonbin 促音便, which replaces the last syllable of the first morpheme by a small tsu っ, which represents a sokuon (geminate consonant).

- sessuru

接する

To touch. To come in contact with.- c.f.: setsu-zoku 接続, "connection."

- tassuru

達する

To reach a goal, a destination.- c.f. tatsu-jin 達人, "expert," "master," in the sense of reached the height of skill.

- dassuru

脱する

To escape.- c.f. datsu-goku 脱獄, "escaping from prison."

~ずる

In some words, ~suru ~する has become ~zuru ~ずる(ja.wikipedia.org:行変格活用). This is a change in pronunciation called rendaku 連濁, through which ~suru gained a dakuten 濁点 diacritic. For example:

- meizuru

命ずる

To order. To command.

- c.f. meirei 命令, "command."

- kinzuru

禁ずる

To forbid. - enzuru

演ずる

To play a role (in an act). To act a part.

Words that end in ~zuru are still technically considered sa-hen サ変, as ~zu is treated as a mere diacritical change. The conjugation should be the same as other sa-hen doushi, except with diacritcs. In practice, however, it seems there are many exceptions, and most forms would be extremely unusual if seen in modern Japanese.

| Form | Conjugation |

|---|---|

| mizenkei 未然形 |

za~, ji~, ze~ ざ~, じ~, ぜ~ |

| ren'youkei 連用形 |

ji~ じ~ |

| shuushikei 終止形 |

zu ず |

| zuru ずる |

|

| rentaikei 連体形 |

zuru ずる |

| izenkei 已然形 |

zure~ ずれ~ |

| meireikei 命令形 |

zeyo ぜよ |

| jiro じろ |

In some cases, an n ん may be inserted at morpheme boundary, forming ~n-zuru ~んずる.

- omonzuru

重んずる

To think high of. To respect.

- c.f. omoi 重い, "heavy."

- karonzuru

軽んずる

To think low of. To belittle.

- c.f. karui 軽い, "light," karoyaka 軽やか, "non-serious," "minor (issue)."

~じる

The ~jiru ~じる suffix is an alternative way to conjugate ~zuru ~ずる. There's no difference in meaning between ~jiru and ~zuru,(金城,2012:69), if a ~zuru words means something, its ~jiru counterpart means the same thing. For example:

- meijiru

命じる

To order. (same as meizuru.) - kinjiru

禁じる

To forbid. (same as kinzuru.) - enjiru

演じる

To play a part. (same as enzuru.)

In fact, the ~jiru suffix is far more commonly used than the ~zuru suffix in modern Japanese (around 3 times more). Only in a few words the ~zuru suffix is more common, and in some cases both are used with similar frequency.

| Word | Occurences | |

|---|---|---|

| ~jiru | ~zuru | |

| kanjiru, kanzuru 感じる, 感ずる |

3555 | 301 |

| shoujiru, shouzuru 生じる, 生ずる |

2463 | 944 |

| shinjiru, shinzuru 信じる, 信ずる |

978 | 307 |

| tsuujiru, tsuuzuru 通じる, 通ずる |

909 | 264 |

| enjiru, enzuru 演じる, 演ずる |

393 | 98 |

| ronjiru, ronzuru 論じる, 論ずる |

362 | 245 |

| oujiru, ouzuru 応じる, 応ずる |

337 | 132 |

| meijiru, meizuru 命じる, 命ずる |

240 | 217 |

| junjiru, junzuru 準じる, 準ずる |

43 | 223 |

| omonjiru, omonzuru 重んじる, 重んずる |

147 | 69 |

| tenjiru, tenzuru 転じる, 転ずる |

110 | 50 |

| anjiru, anzuru 案じる, 案ずる |

51 | 90 |

| kinjiru, kinzuru 禁じる, 禁ずる |

61 | 67 |

| toujiru, touzuru 投じる, 投ずる |

52 | 35 |

| houjiru, houzuru 報じる, 報ずる |

36 | 33 |

Some instances where ~jiru isn't used include authoritative phrases like kinzuru, "to forbid," ninzuru 任ずる, "to appoint (in the sense of giving a mission to someone)," which are likely used in very formal, government texts.

The phrase anzuru na 案ずるな, "don't falter," is also typically in this ~zuru form. Almost everything else leans to ~jiru.

In anime, characters that speak archaically, e.g. kings, old mages, deities, etc., may use ~zuru where normally you'd expect ~jiru.

Note that this choice depends on their typical manner of speaking (idiolect): someone who normally uses ~zuru with a word will probably always use it.

Words that end in ~jiru aren't considered sa-hen. They conjugate like ichidan verbs instead(ja.wikipedia.org:行変格活用), specifically this would be kami-ichidan-katsuyou 上一段活用, as ~jiru ends in ~iru.

| Form | Conjugation |

|---|---|

| mizenkei 未然形 |

ji~ じ~ |

| ren'youkei 連用形 |

ji~ じ~ |

| shuushikei 終止形 |

jiru じる |

| rentaikei 連体形 |

|

| izenkei 已然形 |

jire~ じれ~ |

| meireikei 命令形 |

jiyo じよ |

| jiro じろ |

For example, kinzezu 禁ぜず and kinjizu 禁じず, both "without forbiding," would be the zu-form of kinzuru and kinjiru, respectively.

Irregular Cases

A few words have irregular suru conjugations.

- sa~ instead of shi~ or se~ for mizenkei.

- aisanai (instead of ai shinai)

愛さない(愛しない)

To not love. - aisazu (ai sezu)

愛さず(愛せず)

Without loving.

- aisanai (instead of ai shinai)

- Conjugating passive, potential and causative as an ichidan verb ending in ~seru.

- hasserareru (hassareru)

発せられる(発される)

To be emitted. - hassesaseru (hassareru)

発せされる(発させる)

To make emit.

- hasserareru (hassareru)

- ~zuru using ~ze or ~ji instead of ~za for the mizenkei.

- shinjirareru (shinzareru)

信じられる(信ざれる)

To be believed.

To be able to believe. - enzesaseru (enzaseru)

演ぜさせる(演ざせる)

To make [someone] play a part.

- shinjirareru (shinzareru)

Grammar Syntax

The suru-verbs aren't very complicated at first glance. You have a word, you add suru to it, it becomes a verb, then you conjugate the suru part, and that's about it. For example:

- Context: teaching someone how to use a computer.

- kore wa?

これは?

This thing [is]? - mausu. {sore wo tsukatte}

sousa suru no yo

マウス それを使って操作するのよ

Mouse. {Using that thing} [you] operate [the computer].- sousa

操作

Operation. (of a device.) - sousa suru

操作する

To operate a device, such as a computer.

- sousa

Although suru-verbs may appear to be a single word made of two inseparable parts at first glance, that's not actually the case, and a lot of trouble stems from this.

A suru-verb is a verbal phrase made out of two words: the verb suru, which means "to do," and a verbal noun that refers to what we're doing.

- kekkon

結婚

Marriage. - kekkon suru

結婚する

To do "a marriage."

To marry.

[I] do "a marriage."

[I] marry. - kekkon shita

結婚した

[I] did "a marriage."

[i} married.

When put this way, it appears kekkon is the direct object for the verb suru, making suru a transitive verb, just like "to do" in English. This is sort of true, but it's a little more complicated than that.

See also: Subject and Object.

For starters, suru only means "to do" when it's a accompanied by the noun that contains what we're doing. It's not possible to say "I'm gonna do it" with suru alone, for example, if we don't have a verbal noun somewhere saying what action "it" is supposed to be.

Given that suru can't be used without the verbal noun, it's said to be an auxiliary verb, as opposed to a main verb. It's also called a semantically light verb, in the sense that it doesn't have enough meaning on its own to work as a standalone word and is only part of the language for grammatical purposes.

In specific, since we can't conjugate nouns, but we can conjugate verbs, so the purpose of suru is simply to allow us to conjugate the verbal noun as if it were a verb, and what suru alone means or doesn't mean doesn't really matter that much.

- ansatsu

暗殺

Assassination.- This is a noun, so we can't conjugate it.

- ansatsu suru

暗殺する

To assasssinate.- Now it's a verb, and we can conjugate it!

- There's little point in thinking of this as "to do an assassination," since the purpose of suru is merely to make ansatsu a verb, just think of it as "to assassinate."

Japanese also has another word that means "to do," yaru やる, which, unlike suru, can be used by itself:

- yaru zo!

やるぞ!

[I]'ll do [it]!

This word isn't interchangeable with suru. It just happens to translate to the same thing.

- *kekkon yaru

結婚やる

More technically, yaru is about doing an actual task, physically in the world, while suru is just a grammatical thing.

There are some cases where what a verbal noun means as a verb is different from what you think it means from looking at the dictionary. For example:

- soudan

相談

Consultation. Discussion.

When this word is turned into a suru verb, it means you are asking someone for help, like:

- sensei to soudan suru

先生と相談する

To consult with the teacher.

To ask the teacher for advice.

There's another way to use this word that means giving advice:

- soudan ni noru

相談に乗る

To "ride" consultation. (literally.)

To accept consultation.

To be okay with listening to someone's worries.

〇〇をする

In a phrase such as "to do it" in English, the word "it" is the direct object of the verb "to do." This makes one wonder if the same thing applies to the verb suru する in Japanese: whether or not we can mark the verbal noun with the wo を particle, which marks the accusative case (the direct object).

The answer is: sort of. In principle, we can do it, for example:

- kekkon wo suru

結婚をする

To do a marriage.

To marry.- c.f.:

- banana wo taberu

バナナを食べる

To eat a banana.

However, it's not that simple.

There are suru-verbs that can be separated into verbal noun and suru, and a wo を particle can be inserted in the middle, such that both 〇〇する or 〇〇をする forms are alright—these are called "separable verbs," bunri-doushi 分離動詞. There are also verbs with which this isn't done, and only 〇〇する is valid. Most complicately, there seems to be also verbs that were originally 〇〇をする, but wo を gets omitted, and they end up looking like 〇〇する.(加藤, 2006:25–26)

To make it more simple: assume you can't say ~wo suru, unless it sounds like a physical task someone deliberate does, for example:

- shigoto wo suru

仕事をする

To work.

To do one's job.

In cases where either form is alright, ~wo suru generally emphasizes the act of doing the thing. For example, kekkon wo suru emphasizes the act of doing a marriage.

〇〇がしたい, 〇〇ができる

Some conjugations change the verb from transitive to intransitive, which means a verb that had a direct object previously won't have a direct object anymore, so nothing is going to get marked by the wo を particle anymore..

See also: Transitive and Intransitive Verbs.

Namely, the tai-form (want to do) and the potential form (can do) cause loss of transitivity. The resulting sentence structure is a double subject construction, which means, in practice, that wo を particle becomes a ga が particle.

This also applies to ~wo suru, with ~wo suru becoming ~ga shitai and ~ga dekiru in the tai-form and potential form, respectively. Observe:

- watashi wa kekkon wo suru

私は結婚をする

I marry.

I will marry.- watashi wa banana wo taberu

私はバナナを食べる

I eat bananas.

I will eat a banana.

- watashi wa banana wo taberu

- watashi wa {kekkon ga shitai}

私は結婚がしたい

{To marry is wanted} is true about me.

I want to marry.- watashi wa {banana ga tabetai}

私はバナナが食べたい

I want to eat a banana.

- watashi wa {banana ga tabetai}

- watashi wa {kekkon ga dekinai}

私は結婚ができない

{To marry isn't possible} is true about me.

I can't marry.- watashi wa {banana ga taberarenai}

私はバナナが食べられない

I can't eat a banana.

- watashi wa {banana ga taberarenai}

Just like we can say kekkon wo suru or kekkon suru, it's also possible to omit the ga が particle in cases such as above:

- watashi wa {kekkon shitai}

私は結婚したい

I want to marry. - watashi wa {kekkon dekinai}

私は結婚できない

I can't marry.

The ~yasui ~やすい, ~nikui ~にくい, and ~gatai ~がたい suffixes also intransitivize suru into ~ga shiyasui ~がしやすい, ~ga shinikui ~がしにくい, and ~ga shigatai ~がしがたい.

With sa-hen verbs featuring a bound morpheme (like teki-suru), you can't split teki~ and ~suru, so you can't put a wo を before suru, nor can you put a ga が before an intransitivization of suru.

This is generally not a problem since such verbs tend to feature a change in pronunciation that makes them distinguishable from a suru-verb (e.g. sessuru, anzuru), except some of them look separable at first glance, for example:

- do-shigatai

度し難い

Hard to persuade-and-make-understand.

Even if you tried to persuade them, you don't think they'd understand.

They're irredeemable. Beyond salvation.- do-suru

度する

To persuade someone to understand.

To make them see the truth, the logic, to make them see the light.

To redeem. To save. (from saido 済度, "salvation," Buddhist term.) - The word do-suru is inseparable, so we can't say do wo suru, nor do ga shigatai, even though at first glance it looks like we could.

- do-suru

Double を Constraint

An issue occurs when the verbal noun has its own direct object. For example, if we said:(next three examples from 柴谷方良, 1978, as cited in 中村, 2003:151)

- Tarou wa benkyou wo shita

太郎は勉強をした

Tarou did "a study."

Tarou studied.

Then, benkyou, "study," is the direct object for the verb suru, "to do," or rather, its past form: shita した, "did." Meanwhile, if we said:

- Tarou wa eigo wo benkyou shita

太郎は英語を勉強した

Tarou studied English.

Then eigo, "English," is the direct object for the verbal phrase benkyou shita, "studied."

However, if we said:

- *Tarou wa eigo wo benkyou wo shita

太郎は英語を勉強をした

Intended: "Tarou studied English."

Then that's grammatically wrong.(柴谷方良, 1978, as cited in 中村, 2003:151)

As a general rule in case grammar, each clause has only one verb, each noun in a clause has only one function (case), and two nouns can't have the same function in a single clause.

This means if there's already a noun functioning as the direct object, we can't have a second direct object. You can only have one per verb.

Above, we only have one verb, suru, and there can only be one direct object for suru: which it's either eigo or benkyou, it can't be both.

- In phrases like ringo to banana wo taberu リンゴとバナナを食べる, "to eat an apple and a banana," the phrase "an apple and a banana" still only counts as one noun phrase, so there's only one direct object.

The same principle applies to causative sentences. For example, we can say:

- Hanako wa hon wo yonda

花子は本を読んだ

Hanako read a book.

And we can say:

- Tarou wa Hanako wo yomaseta

太郎は花子を読ませた

Tarou caused Hanako to read.

Tarou made/let Hanako read.

But we can't say:(柴谷方良, 1978, as cited in 中村, 2003:151)

- Tarou wa Hanako wo hon wo yomaseta

太郎は花子を本を読ませた

Intended: "Tarou caused Hanako to read a book."- Instead, the correct is to mark the causee with the ni に particle:

- Tarou wa Hanako ni hon wo yomaseta

太郎は花子に本を読ませた

Tarou caused Hanako to read a book.

Tarou made/let Hanako read a book.

With a suru-verb, if we want to mark its direct object with wo を, we can't mark the verbal noun with the wo を, too, so wo を gets removed from after the verbal noun.

- Tarou wa eigo wo benkyou shita

太郎は英語を勉強した

Tarou studied English.

Japanese grammar is based mostly on marking stuff with particles, so it would be weird for a particle to vanish leaving nothing in place. In such cases, we pretend "nothing" is actually an invisible particle, the null particle, which we can represent by this φ (null symbol), like this:

- kakunin wo suru

確認をする

To do a confirmation. - *naiyou wo kakunin wo suru

内容を確認をする - naiyou wo kakunin φ suru

内容を確認する

To confirm the contents [of a book, story, script, or other publication].

Any case we would have two wo を, we have to drop the wo を before suru する, and if we want to get technical, we say wo を was replaced by the null particle.

Note that due to the rules previously explained, this means that the verb of the clause above is actually suru, not kakunin suru, and kakunin is takes some sort of role marked by the null particle. This role can't be the direct object, because we already have a direct object.

I have no idea what role it's supposed to be exactly, but considering how everything works, it's safe to assume kakunin and suru are separate, kakunin is a noun used by suru somehow, and in practice this barely matters most of the time, so I'm not going to waste my time putting a φ (null symbol) before every single suru, and we're just going to pretend suru works like a suffix and we only have one word, like kakunin-suru, because life is simpler that way.

~の~をする

With some nouns it's also possible to replace wo を by no の, changing the direct object of the suru-verb into a no-adjective qualifying the verbal noun, making the verbal noun more specific to the point it doesn't need a direct object. For example:

- naiyou no kakunin wo suru

内容の確認をする

To do "the confirmation of the contents."

To confirm the contents.

Above, the noun phrase naiyou no kakunin is the direct object for the verb suru, which means, since we're dividing these into verbal noun plus suru, that the verbal noun in this case is the phrase naiyou wo kakunin.

We can also drop the wo を in this case:

- naiyou no kakunin φ suru

内容の確認する

Unaccusative Restriction

Not all suru-verbs are used in the ~wo suru ~をする pattern, so one wonders which ones you can't use with wo を, and why?

According to Sakamoto 坂本 (2013:77), you can't use the ~wo suru pattern with "unaccusative verbs," hitaikaku-doushi 非対格動詞. For example, you shouldn't be able to use ~wo suru with the verbs below:

| Verb. | + wo を |

| bakuhatsu suru 爆発する To explode. |

*bakuhatsu wo suru |

| shikyo suru 死去する To die. To pass away. |

*shikyo wo suru |

| tentou suru 転倒する To tumble. |

*tentou wo suru |

| tsuiraku suru 墜落する To fall. To crash. |

*tsuiraku wo suru |

I'm not actually sure how correct this claim is, since you can find a lot of instances of people using bakuhatsu wo suru, for example, on the internet. Regardless, if you're wondering why you can't use ~wo suru with a certain verbal noun, the reason is probably because it's unaccusative.

Now, what does unaccusative mean? Well, wo を marks the accusative case, so unaccusative, being obviously the opposite of that, naturally doesn't work with wo を, but, again, what is it?

Observing the examples cited above, you can already have an idea. None of the verbs listed are stuff the subject can control, interact with, or manipulate, they're simply stuff that happen to the subject.

If you tumble, crash, die, or explode, you aren't in control of these events. These aren't "actions" you've deliberately performed. These are more like "occurrences" that occurred with you. You haven't performed a tumble, a tumble simply occurred.

Compare with:

- sanpo wo suru

散歩をする

To do a stroll.

To stroll.

A stroll is an action you have control over. You can decide where to stroll, how fast to go, when to stop, etc., so it makes sense that it works with the ~wo suru pattern.

It's possible that an unaccusative verb can be used with this pattern if we're deliberately implying that the subject has control over an otherwise uncontrollable situation. For example, if you intended to tumble, and then you deliberately do it, then maybe it makes sense to use ~wo suru in that case.

〇〇はしない

It's also possible to use the wa は particle before suru する, between it and the verbal noun. This means, since wa は is a topic marker, and wa は is coming after the verbal noun, that the verbal noun is being marked as a topic.

See Topic and Focus for details.

This is most likely to occur and understand in negative sentences. For example:

- Presupposition: you'll marry.

- kekkon wa shinai

結婚はしない

To marry, [I] won't.

[I] won't marry.

Above, we have a pressuposition that you'll marry, and an assertion that you won't marry, that is, something thinks that you're going to marry, and you're correcting them, saying that you won't, in fact, marry.

Linguistically, this means kekkon, the act of marriage, is the topic, the idea that it will occur is the pressuposition (old information), while the idea it won't occur is the focus (new information). We assert new information to correct wrong old information.

So the wrong pressuposition was kekkon wa suru 結婚はする, "marriage, [you] will be doing." This is unspoken. Nobody said this sentence. But it's understood from context. To correct this, we changed what came after kekkon wa to negative: kekkon wa shinai.

This may also occur in the form of a contrastive wa は:

- Context: that's so dangerous! What if it explodes?!

- bakuhatsu suru

爆発する

To explore.

- bakuhatsu suru

- iya, bakuhatsu wa shinai daro

いや、爆発はしないだろ

No, exploding, [it] won't.

Come on, [it] won't EXPLODE, don't be ridiculous.- It may do OTHER THINGS, like burning, making infernal, screeching sounds, or spilling acid everywhere, but it won't explode, that's the one thing I can assert it absolutely won't do.

Another case is with questions. The information being sought is the focus of the question, what's not the focus is the topic. When you're talking about the occurrence of something, and the focus is only the "occurrence" part, the "something" part becomes the topic. For example:

- kekkon shita ka?

結婚したか?

Did [you] marry?- Did "marriage" occur?

- iie, kekkon wa shitei-nai

いいえ、結婚はしていない

No, marriage, [I] still haven't done.

No, [I] haven't married yet.- No, "marriage" hasn't occured yet.

Of course, in practice the question is going to look more complicated than this, such as:

- go-kekkon sareta-n-desu ka?

ご結婚されたんですか?

Did [you] marry?- Here, sareru, which looks like the passive of suru, actually has the same meaning as suru, except it's honorific language used in respectful contexts. Similarly, the go~ prefix is also a honorific. It's literally the same thing with a bunch of respect sprinkled on top.

The wa は particle can also be used with other negative sentences, such as:

- kekkon wa shitakunai

結婚はしたくない

Marriage, [I] don't want to do.

[I] don't want to marry. - kekkon wa dekinai

結婚はできない

Marriage, [I] can't do.

[I] can't marry.

And so on.

Note, however, that it's not every negative form of suru that will have a wa before it. Only in cases where the verbal noun is the topic, which isn't every case. For example, we could say:

- watashi wa kekkon shinai

私は結婚しない

I won't marry.

If the topic is me, that is, if it's about whether I'm going to marry, in contrast with other people who will or won't marry.

- watashi wa kekkon wa shinai

私は結婚はしない

With the above, we'd be saying that kekkon, specifically, is something that I won't do, but I may do other things.

Subject Between Verbal Noun and Suru

Although unlikely, because of the versaility of the wa は particleit's possible to rearrange a sentence with the structure above such that the topicalized verbal noun ends up at sentence-initial position, which means, consequently, that the subject ends right before suru, making it look like it's the verbal noun when it isn't. For example:

- kekkon wa watashi wa shinai

結婚は私はしない

Marriage, I won't do.- Here, kekkon, which is at the start of the sentence, is the verbal noun for shinai, which is at the end of the sentence, and watashi is the subject which somehow ended up in the middle.

~も~もしない

It's possible to conjugate multiple verbal nouns with just one suru by chaining them with the mo も particle. This usually happens in the negative, for example:

- shigoto wa shinai

仕事はしない

Work, [she] doesn't. - kekkon mo shinai

結婚もしない

Marriage, [she] doesn't also. - shigoto mo kekkon mo shinai

仕事も結婚もしない

[She] doesn't work, and [she] doesn't marry also.

[She] neither works, nor does [she] marry.

[She] doesn't find a job, but doesn't become a housewife, either.- Today I realized the contemporary female version of NEET is Not in Employment, Education, Training, or Marriage.

This mo も particle works in other sentences that have wa は. For comparison:

- Amerika niwa ikanai

アメリカには行かない

[I} won't go to Amreica. - Kanada nimo ikanai

カナダにも行かない

[I] won't go to Canada, either. - Amerika nimo Kanada nimo ikanai

アメリカにもカナダにも行かない

[I] will go neither to America, nor to Canada.

Other Particles Between Verbal Noun and Suru

Besides wa は and mo も, there are also other particles that can come between the verbal noun and suru, of which there are two types. For reference:

- kekkon sae sureba

結婚さえすれば

If only [I] were to marry. (something like this wouldn't happen, everything would be solved, etc.) - kekkon sura dekinai

結婚すらできない

[I] can't even marry. (even something so easy I can't do!) - kekkon sura dekiru

結婚すらできる

[I] can even marry. (even something so difficult I can do!) - kekkon dake wa shitakunai

結婚だけはしたくない

Only marriage [I] don't want to do.

I might want to do other things, but marriage alone I don't wanna.

Anything but marriage! - kekkon made wa shite-inai

結婚まではしていない

[We] haven't gone as far as marrying. (we have done plenty of things, like living together, but no marriage yet.) - kekkon shika dekinai

結婚しかできない

[I] can't do anything but marry. (marriage is the only option.) - kekkon kurai shinakucha

結婚くらいしなくちゃ

[I] gotta at least marry. (it's around the bare minimum.)

Adverb Between Verbal Noun and Suru

It's also possible to use adverbs after the verbal noun and before suru. For example:

- mada kekkon wa shitei-nai

まだ結婚はしていない

[I] haven't married yet. - kekkon wa mada shitei-nai

結婚はまだしていない

Marriage [I] haven't done yet.

I haven't married yet. - kekkon wa mou shite-iru

結婚はもうしている

Marriage [I] already have done.

I've already married.

Note that some adverbs are in the form of the adverbial copula ni に, which may look like a ni に particle doing something else.

- kekkon wa zettai da!

結婚は絶対だ!

Marriage is absolute! - kekkon wa {zettai ni} shitakunai!

結婚は絶対にしたくない!

Marriage [I] {absolutely} don't want to do!

Relativization

In Japanese, almost anything that can be marked as the topic can be relativized, that is, the focus of the sentence becomes a relative clause qualifying it, for example:

- keeki wa tabeta

ケーキは食べた

Cake, I ate. - {tabeta} keeki

食べたケーキ

The cake [that] {[I] ate}.

This includes even stuff that doesn't make a lot of sense in English, like first person pronouns:

- watashi wa kekkon shita

私は結婚した

I married. - {kekkon shita} watashi

結婚した私

Me, [who] {married}.

Ultimately, this ALSO includes verbal nouns, since verbal nouns can be marked by wa は they can be relativized. The problem is that their predicate is suru する, and it simply makes no sense for suru to come before the verbal noun most of the time:

- kekkon wa suru

結婚はする

Marriage, [I] do. - #{suru} kekkon

する結婚

The marriage [that] {[I] will do}.

The marriage [that] {[one] does}.- Note: "[one] does" usage is a habitual with relativized object and generic subject, which basically ends up meaning it's a "doable" marriage because "one can do it."

The main reason this doesn't work is because the verbal noun is already specific enough that there is no point in qualifying it with a relative clause.

One exception is the light noun koto こと, which translates to simply "thing," or "something," and it's vague enough to be qualified by suru. Observe the sentences below:

- sonna mono wa tabetakunai

そんなものは食べたくない

[I] don't want to eat something like that. - sonna koto wa shitakunai

そんなことはしたくない

[I] don't want to do something like that. - {taberu} mono ga nai

食べるものがない

A thing [that] {[one] eats} doesn't exist.

There's nothing to eat. - {suru} koto ga nai

することがない

A thing [that] {{one] does} doesn't exist.

There's nothing to do.

It's also possible to use a more specific conjugation of suru to qualify the verbal noun in order to restrict the action somehow. For example, if you qualify with shitai, you're referring only to an action you want to do:

- {watashi ga shitai} kekkon wo suru

私がしたい結婚をする

To do a marriage [that] {I want to do}.- As opposed to doing a marriage that I don't want to do.

Similarly, one can use the potential:

- {dekiru} koto wo suru

できることをする

To do the things {[I] can do}.

To do what {[I] can do}.

To do whatever is within my ability.

I guess indefinite pronouns would be the last case where this would make sense:

- nanika ga shitai

なにかがしたい

[I] want to do something. - {shitai} nanika

したいなにか

Something [that] {[I] want to do}.- In the sense of "the thing that I want to do, except I don't know what thing it is exactly, it's something... I don't know what."

Omission in Incomplete Sentences

Like many other verbs, suru is omitted in incomplete sentences that end with the verb's direct object.

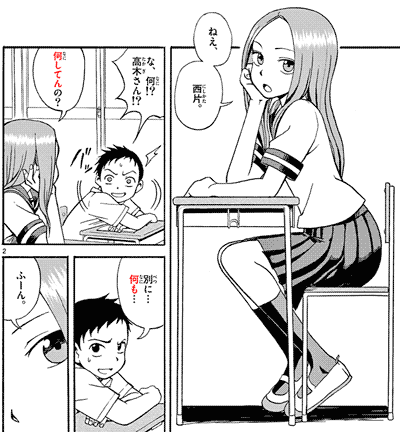

- Context: Takagi 高木 catches Nishikata 西片 acting suspiciously.

- nee, Nishikata.

ねえ、西方。

Hey, Nishikata. - na, nani!? Takagi-san!?

な、何!?高木さん!?

W-what [is it]!? Takagi!? - nani shiten-no?

何してんの?

What are [you] doing?- nani shiten-no~ - contraction of nani shite-iru no 何しているの.

- betsuni...

nanimo...

別に・・・何も・・・

Nothing...

In particular...- nanimo shite-inai

何もしていない

[I] haven't done anything.

- nanimo shite-inai

- fuun.

ふーん。

*suspicious humming of doubt.*

Verbal Nouns

A suru-verb is composed of a noun plus a verb, but that doesn't mean all nouns can become suru-verbs. There are nouns that make sense as verbs and there are those that do not.

For example, akushu 握手, "handshake," is something you can do. You can shake people's hands, so you can akushu suru 握手する, "to shake hands."

Anime: Tsuki ga Michibiku Isekai Douchuu 月が導く異世界道中 (Episode 10, Censored)

- Context: lewd.

Meanwhile, "coffee," koohii コーヒー, isn't something you can do. You can't coffee things, so you can't koohiii suru コーヒーする. That makes no sense.

In general, nouns that refer to activities or their outcomes can become suru-verbs.

This is similar to how the ren'youkei (noun form) of non-suru verbs can also refer to the act of doing the verb or the outcome of the act. So it's the same idea, but with ren'youkei it's verb becoming noun, while with suru-fication, it's noun becoming verb. Observe:

- odoru

踊る

To dance. - odori

踊り

The dancing [of someone]. (as how the process is performed.)

The dance [that someone performed]. (as the finished product.) - renshuu

練習

Training. (the process) - renshuu suru

練習する

To train. - hon'yaku

翻訳

Translation. (the finished product.) - hon'yaku suru

翻訳する

To translate.

Some nouns easily refers to the product of an activity: if you were "to calculate," keisan suru 計算する, when you finish what you'll have in hands is a "calculation," a keisan 計算. Other examples include:

| romaji | Japanese | Noun | + suru する |

|---|---|---|---|

| hoshou | 保証 | A guarantee. | To guarantee. |

| shoumei | 証明 | A proof. | To prove. |

| kyoka | 許可 | A permission. | To permit. |

| meirei | 命令 | An order. | To order someone. |

| chuumon | 注文 | An order. | To order from a shop. |

| tsuuyaku | 通訳 | An interpretation. | To interpret. |

| hon'yaku | 翻訳 | A translation. | To translate. |

| shitsumon | 質問 | A question. | To inquire. |

| mujun | 矛盾 | A contradiction. | To contradict oneself. |

| housou | 放送 | A broadcast. | To broadcast. |

| shuukaku | 収穫 | A harvest. | To harvest. |

| bouken | 冒険 | An adventure. | To adventure. |

| den'wa |

電話 | A phone call. | To phone call. |

Not all activities result in a tangible product. As such, some nouns typically refer to the activity itself instead of any outcome. These are more likely to translate to a gerund in English (noun ending in ~ing).

Generally, this occurs when the noun refers to a physical activity, so the verb refers to performing the action physically, for example:

| romaji | Japanese | Noun | + suru する |

|---|---|---|---|

| sanpo | 散歩 | A stroll. | To stroll. |

| hakushu | 拍手 | An applause. | To applause. |

| aisatsu | 挨拶 | A greeting. | To greet. |

| aizu | 合図 | A sign. A cue. | To make a sign. |

| kokyuu | 呼吸 | Breathing. | To breathe. |

| souji | 掃除 | Cleaning [a room]. | To clean. |

| kaizen | 改善 | Improvement. | To improve. |

| anki | 暗記 | Memorization. | To memorize. |

| renshuu | 練習 | Training. | To train. |

| kankou | 観光 | Sightseeing. | To go sightseeing. |

| gakushuu | 学習 | Learning. | To study. |

The same applies to nouns that refer to some sort of movement, as the verb refers to performing that movement, for example:

| romaji | Japanese | Noun | + suru する |

|---|---|---|---|

| idou | 移動 | Movement. | To move. |

| kaiten | 回転 | Rotation. | To rotate. |

| nyuugaku | 入学 | Entering a school. Enrollment. |

To enroll. |

| nyuuin | 入院 | Entering a hospital. Hospitalization. |

To be hospitalized. |

| nyuusha | 入社 | Entering a company. | To join a company. |

| nyuuyoku | 入浴 | Entering a bath. | To enter a bath. |

| taigaku | 退学 | School expulsion. | To drop out. |

| intai | 引退 | Retirement. | To retire. |

| shuppatsu | 出発 | Departure. (person comes out.) |

To depart. |

| shuppan | 出版 | Publication. (book comes out.) |

To publish. |

| shukketsu | 出血 | Bleeding. (blood comes out.) |

To bleed. |

| nyuuryoku | 入力 | Input. | To input. |

| shutsuryoku | 出力 | Output. | To output. |

| yunyuu | 輸入 | Importation. | To import. |

| yushutsu | 輸出 | Exportation. | To export. |

| kyuushuu | 吸収 | Absorption. | To absorb. |

Some words that refer to physical positions, such as seiza 正座, sitting on one's knees, and dogeza 土下座, a prostrating pose, can also be used as verbal nouns.

- seiza suru

星座する

To do a seiza.

To sit on one's knees. - dogeza suru

土下座する

To do a dogeza.

To prostrate yourself. To be at someone's feet.

Anime: Star☆Twinkle Precure, スター☆トゥインクルプリキュア (Episode 10)

- {petan-zuwari shite-iru} {onna no} ko

ぺたん座りしている女の子

A girl [who] {is doing a petan-zuwari}.

A girl [who] {is W-sitting}.

Some nouns refer to a change of state brought by the action.

| romaji | Japanese | Noun | + suru する |

|---|---|---|---|

| shitsugyou | 失業 | Losing one's job. | To become unemployed. |

| shitsumei | 失明 | Loss of eyesight. | To become blind. |

In particular, any word ending in the ~ka ~化 suffix, which translates to "~fication," can become a suru-verb referring to the process resulting in that change:

| romaji | Japanese | Noun | + suru する |

|---|---|---|---|

| kyouka | 強化 | Strong-fication. Strengthening. |

To strengthen. |

| jakutaika | 弱体化 | Weak-body-fication. Weakening. |

To weaken. |

| shinka | 進化 | Progress-fication. Evolution. |

To evolve. |

| kikaika | 機械化 | Machine-fication. Mechanization. |

To mechanize. |

| jidouka | 自動化 | Automatic-fication. Automation. |

To automate. |

| kouka | 硬化 | Hard-fication. Hardening. |

To harden. |

| ekika | 液化 | Liquid-fication. Liquefaction. |

To liquefy. |

| jouka | 浄化 | Purification. | To purify. |

| sekika | 石化 | Stone-fication. Petrification. |

To petrify. |

| nyotaika | 女体化 | Female-body-fication. Genderbending. |

To turn into a girl. |

| nantaika | 男体化 | Male-body-fication Genderbending. |

To turn into a guy. |

The ~ka suru ~かする verbs are ergative, which is unusual in Japanese. This means, for example, that jouka suru 浄化する can be used both both intransitively, e.g. "the water purifies,".or transitively, "the goddess purifies the water."

See ergative verb pairs for details.

Oddly Specific Suru-Verbs

Due to Japanese's overpowered ability to create complex words out of fragments of other words represented by kanji 漢字, some suru-verbs are nouns formed by the morpheme of a transitive verb with that of a direct object used with that verb, resulting in an oddly specific intransitive suru-verb that translates to a transitive verb in English.

To elaborate, observe the sentence below:

- yama wo noboru

山を登る

To climb a mountain.

Above, we have the direct object yama, "mountain," and the transitive verb "to climb," noboru. The readings of the kanji in this word (山 and 登) are both kun'yomi 訓読み.

Meanwhile, the following word uses on'yomi 音読み readings:

- tozan

登山

Mountain-climbing.

Mountaineering. Alpinism.

And this word, as it refers to an action, can be suru-fied:

- tozan suru

登山する

To do "mountain-climbing."

To mountain-climb.

To climb a mountain.

Above, we ended up with an intransitive verb that refers to a very specific action, "to mountain-climb," and this action would normally be translated as the transitive verb "to climb" together with the direct object "mountain."

As a general rule, when there's a suru-verb like this available in Japanese, it's preferred over the long synonymous phrase, e.g. people would rather say tozan suru than yama wo noboru if it makes sense.

Some other examples:

- gakkou wo kayou

学校を通う

To go to school and come back. (every day.)

To commute to school. - tsuugaku suru

通学する - hone wo oru

骨を折る

To break a bone. - kossetsu suru

骨折する

The verbal noun isn't necessarily the same kanji read as on'yomi. There are also cases where the noun form of a verb that's read in kun'yomi is combined with its direct object as a compound noun. For example:

- mono wo kau

物を買う

To buy things.- Here, mono and kau are kun'yomi.

- kai-mono wo suru

買い物をする

To do "thing-buying."

To go shopping.- Here, kai-mono is a compound noun composed of kai, the noun form of kau, and mono.

The verbal noun doesn't necessarily contain the direct object, either. For example, it could be the noun is composed of the verb plus an adverb instead:

- hiruma ni neru

昼間に寝る

To sleep during the day.

To take a nap. - hirune suru

昼寝する

Neologisms

Since a suru-verb is just slapping suru to another word, it's perfect for creating new verbs out of old words, or even out of new words.

Obvious examples are English loan-words (gairaigo 外来語) and Japanese words made out of English (wasei-eigo 和製英語), such as:

- kopii suru

コピーする

To do "a copy."

To copy. To photocopy. - kopipe suru

コピペする

To copy-paste. - bijinesu wo suru

ビジネスをする

To do business. - kan'ningu suru

カンニングする

To do "a cunning."

To cheat in an exam. - reberu appu suru

レベルアップする

To do "a level up."

To level up.

Another example of neologism comes from the onomatopoeia of a certain revolutionary device:

- chin suru

チンする

To do a "tin."

To microwave [it].- Because a microwave makes a chin チン sound when it finishes microwaving things.

I haven't checked it, but it's possible the reason why so many suru verbs have on'yomi readings, which are the readings kanji originally had in Chinese, is simply because they're Chinese words, or Japanese words made out of what were originally Chinese morphemes, that had suru added to them in order to make them conjugatable in Japanese.

Besides suru, neologisms can be created in Japanese through the ~ru ~る suffix, which spawns godan verbs, and the ~i ~い copulative suffix, which spawns i-adjectives.

- guguru

ググる

To google. To look something up on Google. - emoi

エモい

Emotional. Melancholic.

Pronoun + する

As a general rule, nouns can be replaced by pronouns in whatever syntax is it that requires a noun. Well, suru-verbs are nouns plus a suru auxiliary, so, naturally, the noun that precedes the suru-verb may, too, be replaced by a pronoun.

Unfortunately, however, there are several types of pronouns, they are: interrogative, indefinite, deictic, and anaphoric. Naturally, suru works with any of these, so, naturally, we'll have to see how every one of these works.

Fortunately, it's not as complicated as it sounds. Observe the phrases below:

- watashi wa keeki wo tabeta

私はケーキを食べた

I ate cake.- A simple sentence with a noun.

- watashi wa nani wo tabeta?

私は何を食べた?

I ate what?

What did I eat?- A worrying sentence with an interrogative pronoun.

- watashi wa nani-ka wo tabeta

私は何かを食べた

I ate something.- An even more worrying sentence with a indefinite pronoun.

- watashi wa nani-mo tabenakatta

私は何も食べなかった

I didn't eat anything.

I ate nothing.- A sad sentence with another indefinite pronoun.

- watashi wa sore wo tabeta

私はそれを食べた

I ate that.

I ate the aforementioned thing.

- A context-dependent sentence with either a deictic pronoun or an anaphoric pronoun..

Regarding the last example: when we have a deictic pronoun, we can point to the thing in the context we utter the sentence to refer to it.

- *points to cake*

- I ate that.

The same sentence, "I ate that," doesn't mean "I ate cake" in different context where we don't have a cake to point at. This phenomenon is called deixis. In similar fashion, "I" refers to a different person depending on who is uttering the sentence.

With an anaphoric pronoun, we don't do any pointing, we're simply referring to something someone mentioned previously.

- Did you eat the cake?

- Yes, I did eat that.

The same sentence, "I did eat that," doesn't mean "I ate cake" in a different conversation where something else preceded the pronoun "that," e.g. if the first interlocutor said "did you eat the banana," then "that" refers to "banana" now, and the sentence would mean "I ate the banana" instead.

Now, let's see some examples with suru..

- nani wo suru?

何をする?

What will [you] do? - {nani suru} ki da?

何する気だ?

[You] feel like {doing what}? (literally.)

What do you feel like doing?

What do you intend to do?

- Typically used when someone is about to do something very bad. What are you doing with that knife? What do you intend to do with that?!

- nani shiteru?

何してる?

What are [you] doing?- Contraction of nani shite-iru.

- konkai wa nani wo shita?

今回は何をした?

What did [you] do this time? - nani ga shitai?

何がしたい?

What do [you] want to do? - kisama gotoki ni nani ga dekiru?

貴様ごときに何ができる?

What someone like you can do?- Phrase typically used by the evil guy to gloat about the main character and his nakama being powerless to stop him.

Above we have the interrogative pronoun nani 何, "what," replacing the noun we'd typically attach suru onto. None of these questions need to be answered with a suru verb

- nani shiteru?

- hon wo yonderu

本を読んでる

[I]'m reading a book.

With a suru-verb answer, it's even possible to answer without including suru, since the focus is just the interrogative pronoun:

- nani shiteru?

- ryouri

料理

Cooking.- ryouri wo shite-iru

料理をしている

[I]'m doing "a cooking."

[I]'m cooking.

- ryouri wo shite-iru

- {nani suru} ki da?

- tousou

逃走

Escape.- {tousou suru} ki da!

逃走する気だ!

[He] intends {to escape}!

- {tousou suru} ki da!

Indefinite pronouns are formed in Japanese through the interrogative pronouns plus the ka か particle for "something" and the mo も particle for "not anything," or "nothing."

- {nani-ka wo suru} tame ni

何かをするために

In order {to do something}. - watashi wa nani-mo shitenai yo

私は何もしてないよ

I haven't done anything!- I swear! I'm innocent!

- nani-mo shinaide jitto shitete

何もしないでじっとしてて

Don't do anything, stay still. - nani-mo dekinakatta

何もできなかった

[I] couldn't do anything.

It's unlikely for suru-verbs to be used with deictic pronouns, but it's possible nonetheless. For example:

- *points at someone doing something*

- are ga shitai

あれがしたい

[I] want to do that. - are wo sureba ii

あれをすればいい

If [you] do that, [it] will be good. (literally.)

If you do that, it will work out.

To fix your problem, you should just do that. - are ga dekiru no?

あれができるの?

Can [you] do that?

The suru-verbs are more likely to be used with anaphoric pronouns, in which case it's versatile enough to refer to any action. For example:

- keeki wo tabeta ka?

ケーキを食べたか?

Did [you] eat the cake? - sore wa shite-inai

それはしていない

I haven't done that.

Above, "that" refers to "eating the cake."

The words kou, sou, aa, dou こう, そう, ああ, どう, although they're typically grouped with demonstrative pronouns forming the so-called kosoado kotoba こそあど言葉, aren't technically pronouns.

A pronoun functions as a noun, such that you can replace a noun with a pronoun and the grammar syntax should remain the sameThis is the case with are, a demonstrative pronoun, and nani, an interrogative pronoun.

Meanwhile, kou, sou, aa, dou can't be used as nouns, they're adverbs instead. Since they aren't nouns, they can't be the verbal noun for a suru-verb, which means sentences such as the ones belows are NOT examples of suru-verbs, despite looking very similar to them:

- dou suru?

どうする?

Whare are [you] going to do? - dou shite

どうして

Why. - dou shita no?

どうしたの?

What happened? - kou suru no da!

こうするのだ

[You] do [it] like this!

The examples above are a different usage of suru, most likely the eventivizer usage, given that they all have an unaccusative naru なる counterpart, so they're not suru-verbs, and have little to do with this article.

Null Anaphora

The last and most complicated pronoun that can be suru-fied is... nothing. Literally nothing, which is called "null" or "zero" in linguistics, and we represent by φ or ∅. Observe the sentences below:

- chanto benkyou shita?

ちゃんと勉強した?

Did [you] study properly? - φ shite-nai

してない

[I] haven't done [it].

No, I didn't study properly.

Above, suru する is used without a noun in the answer sentence. As we already know, we can't use suru without a noun that describes the action being done. How does the above work, then?

Simply put, "nothing" works as an anaphoric pronoun in this case, and since it's technically a pronoun, suru technically has a noun describing its action, so the grammar is technically correct, the best kind of correct.

To reiterate: this null pronoun means we're referring to a noun used previously. We aren't using suru alone. The noun for suru above is benkyou, which is in another sentence, uttered by a different interlocutor, but available in context nevertheless.

It's also possible.to use the null pronoun to refer to a noun in the same sentence:

- tenshoku shitai kedo φ shinai

転職したいけどしない

[I] want to change jobs, but [I] won't change jobs. - tenshoku shitai kedo φ dekinai

転職したいけどできない

[I] want to change jobs, but [I] can't change jobs.

Note that the same principle applies to English: if we said "I want to X, but I can't," what we mean is "I want to X, but I can't X."

The phrases "I can't," "I didn't," and so on are auxiliaries and they don't make sense without a verb, so when it looks like there is no verb, it turns out that, grammatically, there is a verb, but it's a verb that's not explictly uttered.

This non-uttering is a referred to a previously uttered verb, and it's called a null anaphora, or, in English, a VP-ellipsis, because the verb phrase is elided (meaning omitted).

Some sentences look like they have a null pronoun but they do not. Observe:

- shimasen yo, sore wa

しませんよ、それは

[I] won't do, that.

Above, the noun for suru isn't null, but sore. But wait, why is the noun coming AFTER suru instead of preceding it? In this case, we say that sore wa, which should be before suru, is dislocated to the right of the sentence.

See dislocation for details.

The non-dislocated sentence would be:

- sore wa shimasen yo

それはしませんよ

Compare with:

- dare da, omae?

誰だお前? - omae wa dare da?

お前は誰だ?

You are who?

Who are you?

〇〇ことする

The semantically light noun koto 事 can be used with the semantically light verb suru する to create verbs out of adjectives, allowing you to talk about doing actions that you can describe by adjectives, rather than by nouns. Observe:

- {warui} koto

悪いこと

Something [that] {is bad}.

Bad things. - {warui} koto wo suru

悪いことをする

To do something [that] {is bad}.

To do bad things.

Above, we're talking about doing something, but we haven't specified exactly what it is. What is "something bad"? Is murder bad? Is stealing food to feed war orphans bad? Is binging all 103 episodes of D.Gray-Man in a single weekend bad? I mean, you have to be more specific than that.

With koto we don't need to be specific. It's the same grammar as other suru-verbs, except that we don't provide an exact action as a noun, only a description of the sort of action we're talking about doing through an adjective plus koto. Other examples:

- {ii} koto wo suru

いいことをする

To do something [that] {is good}.

To do good things. - {yokei na} koto wo suru

余計なことをする

To do something [that] {is unnecessary}.

To do unnecessary things.- It's because you did something you didn't have to do that we got ourselves into this mess!

The wo を may be omitted in this usage, too:

- {{warui} koto φ shitara} Santa-san φ konai yo

悪いことしたらサンタさん来ないよ

{If [you] do something {bad}}, Santa won't come.

If you do bad things, Santa won't visit you.

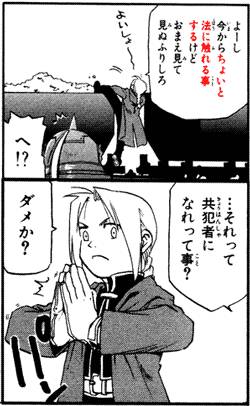

- Context: Edward Elric エドワード・エルリック drags his younger brother into a life of crime.

- yooshi

よーし

Aaalright. - ima kara {choito hou ni fureru} koto suru kedo

今からちょいと法に触れる事するけど

[Starting] now, [I] will do something [that] {violates the law a bit}.- choito

ちょいと - chotto

ちょっと

A bit. A little. - hou ni fureru

法に触れる

To touch the law. To collide with the law. To violate the law. - fureru

触れる

To touch. (as a matter of fact: ended up touching, brushing against.)- sawaru

触る

To touch. (intentionally: he touched the cat, petting it.)

- sawaru

- choito

- omae φ {mite-minu} furi shiro

おまえφ見て見ぬふりしろ

As for you, pretend {not to see [anything]}.- mite

見て

To see, and... - minu furi

見ぬふり

Pretend not to see.

- mite

- yoisho~~

よいしょ~~

[Heave-ho!]- Expression of effort, he used it when climbing.

- he!?

へ!?

[What]!? - ...sore tte hanzaisha ni nare tte koto?

・・・それって犯罪者になれってこと?

...is that: "become a criminal," is what you're saying?- You're telling me to cooperate in a crime!

- dame ka?

ダメか?

Is [that] no good?- Is that not okay?

- Will you not help me?

- pan

パン

*clap*

~ようなことをする

Besides adjectives, it's also possible to describe the koto-action by saying it's simlar to another action through the pattern ~you na koto wo suru ~ようなことをする. For example:

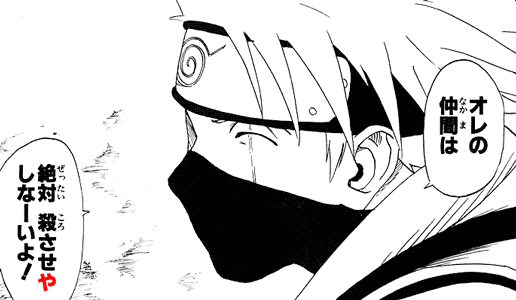

- {kanojo wo kizu-tsuketara} yurusanai

彼女を傷つけたら許さない

{If [you] hurt her}, [I] won't forgive [you]. - {{{kanojo wo kizu-tsukeru} you na} koto shitara} yurusanai

彼女を傷つけるようなことしたら許さない

{{{If [you] do something {like {hurting her}}} [I] won't forgive [you].- If you hurt her, deceive her, disappoint her, buy her ice cream of a flavor she doesn't like, I won't forgive you, alright?

The koto-action also may be qualified by the pronouns konna, sonna, anna, donna こんな, そんな, あんな, どんな, which mean basically the same thing as kono you na このような, etc.

For example, as a question:

- {dono you na} koto wo sureba ii?

どのようなことをすればいい?

What sort of thing should [I] do? - natsuyasumi wa donna koto wo suru?

夏休みはどんなことをする?

What sort of thing do [you] do during summer vacation?

These also work as anaphoric pronouns:

- {sonna koto shitara} shinu zo

そんなことしたらしぬぞ

{If [you] do something like that}, [you] will die. - {{sono you na} koto shitara} shinu yo

そのようなことしたら死ぬよ

Noun Form of Non-Suru-Verbs + する

The noun form of non-suru verbs can be used as the verbal noun for suru, which honestly doesn't really make a lot of sense. For example:

- shiharau

支払う

To pay. - shiharai

支払い

Payment. - shiharai wo suru

支払いをする

To do the payment.

To pay.

As you can see above, if we conjugate shiharau to its ren'youkei and add wo suru to it, we end up with literally the same thing as shiharai, and we're left wondering why did we even go through the trouble of doing all this in the first place.

Well, there's one case where this is useful.

In Japanese, it's possible to insert the wa は particle before all sorts of auxiliaries to topicalize the stem, except for the jodoushi 助動詞. Observe below:

| Base | Stem topicalization |

| kawaii 可愛い [It] is cute. |

kawaiku wa aru 可愛くはある Cute, [it] is. |

| kawaikunai 可愛くない [It] isn't cute. |

kawaiku wa nai 可愛くはない Cute, [it] isn't. |

| tabete-iru 食べている [He] is eating. [He] has eaten. |

tabete wa iru 食べてはいる Eating, [he] is. Eaten, [he] has. |

| tabeta 食べた [He] ate. |

*tabe wa ta |

| tabenai 食べない [He] doesn't eat. [He] won't eat. |

*tabe wa nai 食べはない |

Above, we see that we can't separate the jodoushi ~ta and ~nai from the verb tabe~.

We can separate ~nai from kawaiku because that ~nai isn't a jodoushi, it's a hojo-keiyoushi 補助形容詞 instead. One difference is that that ~nai has an ~aru counterpart, but there's no tabe-aru counterpart for tabenai.

This creates a a bit of a problem when mixing suru-verbs with non-suru-verbs. For example, with suru-verbs, we can topicalize two verbal nouns in separate clauses to create a contrast, like this:

- ryouri wa shinakatta ga, souji wa shita

料理はしなかったが、掃除はした

Cooking, I didn't, but cleaning, I did.

I didn't cook the food, but I did clean the place.

But if we can't do the same thing with a non-suru-verb, because the word isn't splittable:

- *ryouri wa shinakatta ga, tabe wa ta

料理はしなかったが、たべはた

Intended: "cooking, [I] didn't, but eating, [I] did."- ta wa beta also doesn't work.

The solution in this case it to turn the non-suru verb into a noun by conjugating it to its noun form (the ren'youkei). Once it's a noun, it will be a noun referring to an action, which means it can be suru-fied into a suru-verb. Observe:

- ryouri wa shinakatta ga, tabe wa shita

料理はしなかったが、食べはした

Cooking, [I] didn't, but eating, [I] did.

The same applies to the other topicalization usage:

- nigenakatta?

逃げなかった?

[You] didn't run away? - nige wa shinai

逃げはしない

Running away, [I] won't.

It also works with mo も:

- ore wa kakure mo nige mo shinai

俺は隠れも逃げもしない

I, hide or escape, won't do.

I won't hide or run away.- Phrase used when a character is about to fight a bad guy who expects him to cower in fear.

In some cases, this wa は is pronounced ya や instead.

Other する

It's important to note that suru has other uses that may look like suru-verbs, but aren't.

For example, suru する can mean "to wear" sometimes, and to assume an appearance or role as well:

- yubiwa wo suru

指輪をする

To wear a ring. - masuku wo suru

マスクをする

To wear a mask - aite wo suru

相手をする

To be the partner of [someone in an activity].

To be the opponent of. - hen na kakkou wo suru

変な格好をする

To be dressed weird.

It can also mean to have a certain profession. In this case, it's synonymous with yaru やる, "to do."

- shousetsuka wo shite-imasu

小説家をしています

[I]'m working as a novelist.

[I]'m a novelist. - shousetsuka wo yatte-imasu

小説家をやっています

A suru-verb is based on the "to do~," ~wo suru 〇〇をする grammar syntax, and just happen to end up without the wo, turning into 〇〇する sometimes. There are cases 〇〇する is actually ~ga-suru 〇〇がする, which means it isn't a suru-verb.

In particular, this occurs with psychomimetic reduplications in double subject constructions, such as:

- wakuwaku φ suru

わくわくする

To feel excited. - iraira φ suru

イライラする

To feel irritate.

To elaborate, suru する can mean something emits a given sensation to you. For example:

- oto ga suru

音がする

Emits a sound.

Sounds of. - nioi ga suru

匂いがする

Emits a smell.

Smells of. - aji ga suru

味がする

Emits a taste.

Tastes of.

Sentences such as these can be used in double subject constructions.

- soto wa {ame no nioi ga suru}

外は雨の匂いがする

{It smells of rain} is true about outside.

Outside smells of rain.

In some cases, the wa は and ga が particles marking the large and small subjects in such sentences are omitted. When this happens, we call the particle omission a null particle, represented by φ.

- watashi φ {wakuwaku φ suru}

私わくわくする

{It feels exciting} is true about me.

I'm excited about [it].

The same logic applies even to insane stuff like this:

- kono koohii φ... {anmari koohii-koohii φ shitenai}!

このコーヒー・・・あんまりコーヒーコーヒーしてない!

This coffee... {[it] isn't very coffee-coffee}!- i.e. it doesn't emit a feeling that it's coffee-y.

- —anime: Nichijou 日常.

Lastly, suru する is the lexical causative verb in the ergative verb pair of eventivizers naru-suru. Observe:

- yasui

安い

To be cheap. - yasuku naru

安くなる

To become cheap.

Will be cheap. - yasuku suru

安くする

To make [something] become cheap.

The gist of it is that if naru means "to become X," then suru means "to make X become Y."

This mainly occurs because statives in Japanese don't have a future tense, while eventive verbs do, so naru is an eventive verb used to give statives like yasui a future tense, while suru is an eventive verb that means "to cause something to naru."

Interestingly, while this suru is an eventive verb, the suru used with feelings is a stative verb, which means you can use one suru to eventivize the other suru, like this monstrosity:

- {{oto ga suru} you ni} suru

音がするようにする

To make [it] {in a way [that] {[it] emits a sound [of something]}}.- Although this makes some sense, you're more likely to see the negative in practice:

- {{oto ga shinai} you ni} suru

音がしないようにする

To make [it] {in a way [that] {[it] doesn't emit a sound [of something]}}.

To make [a device] silent.

References

- 中村暁子, 2003. 現代語における二重ヲ格について. 岡大国文論稿, (31), pp.152-143.

- 加藤重広, 2006. 二重ヲ格制約論. 北海道大学文学研究科紀要, 119, pp.左-19.

- 金城克哉, 2012. 2 つの異形態動詞 「X じる」 と 「X ずる」 のジャンルごとの分布とコロケーション特徴:「現代日本語書き言葉均衡コーパス」(BCCWJ) を利用した研究. Southern review: studies in foreign language & literature, (27), pp.69-82.

- 坂本勉, 2013. 日本語における自動詞と名詞句の結合違反について: 評定値実験の結果を基に.

- おは・す 【御座す】 - 学研全訳古語辞典 via kobun.weblio.jp, accessed 2021-11-20.

- サ行変格活用 - ja.wikipedia.org, accessed 2021-12-30.

Hey, do you study linguistics in university or why are your articles so detailed, with a lot of written hight quality sources?

ReplyDeleteAnyways, you had an example that said "nanimo + negated verb".

I'm confused by nanimo, could we also use "nanimonai + verb" to say the same thing?

No, I just have a blog. They're detailed probably because I have a programming background so I end up making articles that resemble documentation pages. They have sources because I learned after writing a handful of articles that I too often get things wrong, or I forget where I read something, so I've learned to cite when I can't prove it with examples.

DeleteWith interrogative pronouns, such as nani, you have patterns such as:

1: nani wo suru = do what?

2: nanika wo suru = do something

3: nanimo shinai = do nothing (don't do anything)

4: nandemo suru = do whatever it is (do anything)

The phrase "nanimo nai" is actually the 3rd pattern above. You can't say nanimonai + verb, because it's already nanimo + negated verb. The "nai" here is the negative form of aru.

1: nani ga aru = there is what? What is there?

2: nanika ga aru = there is something.

3: nanimo nai = there is nothing.

4: nandemo aru = there is whatever it is. There can be anything. Anything can occur, anything is possible.