In Japanese, the sa-form, sa-kei サ形, is a form of adjectives that ends in ~sa ~さ, and works like "~ness," "~less," or "~ity" in English, a noun referring to "how much" of a given quality something has. The resulting word is also known as a sa-meishi さ名詞, "sa-noun." For example:

- aimai-sa

曖昧さ

Vagueness. Vaguity.

How vague [it] is. - neko no kawai-sa

猫の可愛さ

The cuteness of cats.

How cute cats are. - umi no kirei-sa

海の綺麗さ

The prettiness of the sea.

How pretty the sea is. - un no na-sa

運のなさ

The nonexistentialness of luck.

The lack of luck.

How little luck [someone] has.

Note that sa さ has other uses, e.g. kirei sa 綺麗さ may mean "it's pretty, you see." The pronunciation differs: in this case, the word kirei is pronounced normally and sa separately, while in the sa-form, kirei-sa is pronounced as a single word, without pause between kirei~ and ~sa, which changes the pitch accent of kirei~. In text, this is a bit difficult to explain, but if you listen to these two different sa's being used a few times, you'll easily understand their difference.

See sa さ particle for other uses of sa さ.

Manga: School Rumble, スクールランブル (Chapter 70)

Manga: Kaguya-sama wa Kokurasetai ~Tensai-Tachi no Ren'ai Zunousen~ かぐや様は告らせたい~天才たちの恋愛頭脳戦~ (Chapter 96)

Conjugation

The sa-form is conjugated by replacing the copula of an adjective by a ~sa ~さ suffix. With i-adjectives, this means replacing the ~i ~い suffix with ~sa. With na-adjectives and no-adjectives (nouns), this means replacing the da だ copula with ~sa.

| Nonpast form | sa-form |

|---|---|

| kawaii 可愛い To be cute. |

kawai-sa 可愛さ Cuteness. How cute it is. |

| kirei da 綺麗だ To be pretty. |

kirei-sa 綺麗さ Prettiness. How pretty it is. |

| futsuu da 普通だ To be normal. |

futsuu-sa 普通さ Normalness. How normal it is. |

The form only makes sense with adjectives, since adjectives express qualities, and the sa-form refers to the quantity of a given quality.

There's no sa-form for verbs, but note that some verbs may share a stem (a.k.a. a root) with an adjective, and that adjective may have a sa-form, which may look like the verb has a sa-form when it doesn't. For example:

- kanashimu

悲しむ

To feel sad.

- This is a godan verb ending in ~mu.

- kanashii

悲しい

To be sad.- This is an i-adjective that shares a kanashi~ stem with kanashimu.

- kanashi-sa

悲しさ

Sadness.

How sad someone is.- This is the sa-form of the i-adjective.

Compare with:

- nusumu

盗む

To steal.- This is a godan verb ending in ~mu.

- *nusui

盗い

- This isn't a word.

- *nusu-sa

盗さ

- This is also not a word, because nusui doesn't exist, and you can't conjugate nusumu to sa-form to heave "stealness" or "how steal something is," whatever that's supposed to mean..

The ~sou ~そう suffix attaches to the sa-form of ii いい (yoi よい), "good," and nai ない, "nonexistent," when it's not an auxiliary adjective, but it doesn't translate to "~ness" in this case:

Grammar

The sa-form refers to the quantity of a quality. The quality is expressed by an adjective word, and its quantity (its sa-form) is syntactically a noun instead. This means that it can be marked by subject markers and get qualified by no-adjectives, like any other noun.

- fuyu no samu-sa ga kibishii

冬の寒さが厳しい

The coldness of the winter is harsh.- Here, "coldness" is the subject of the sentence, marked by the ga が particle, and it's also a noun qualified by the possessive no-adjective fuyu no, "of the winter."

The easiest to understand example of this are adjectives that refer to measurements, because their sa-forms translate to English as completely different nouns that also refer to measurement. Observe:

| Nonpast form | sa-form |

|---|---|

| X ga omoi 〇〇が重い X is heavy. |

X no omo-sa 〇〇の重さ The heaviness of X. How heavy X is. X's weight. |

| X ga takai 〇〇が高い X is high. X is tall. X is expensive. |

X no taka-sa 〇〇の高さ The highness/tallness/expensiveness of X. How high/tall/expensive X is. X's height/value. |

| X ga nagai 〇〇が長い X is long. |

X no naga-sa 〇〇の長さ ?The longness of X. How long X is. X's length. |

| X ga fukai 〇〇が深い X is deep. |

X no fuka-sa 〇〇の深さ The deepness X. How deep X is. X's depth. |

The "~ness" translation sounds weird almost every time, but it's the closest one to how the Japanese grammar works. An example in practice:

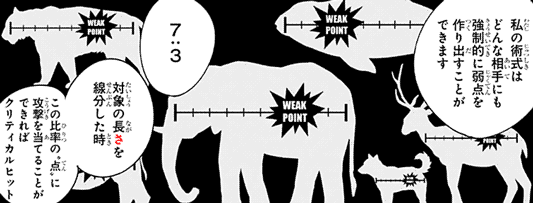

- Context: Nanami Kento 七海建人, an ex-salaryman, explains how his power works.

- watashi no jutsushiki wa {donna aite nimo kyousei-teki ni jakuten wo tsukuri-dasu} koto ga dekimasu

私の術式はどんな相手にも強制的に弱点を作り出すことができます

My technique can {forcibly create a weak-point on any sort of opponent}. - nana tai san

7:3

Seven to three.- See shichi-san-wake 七三分け for the significance of this ratio.

- {taishou no nagasa wo senbun shita} toki

対象の長さを線分した時

When {dividing the target's length (longness)}... - {kono hiritsu no "ten" ni kougeki wo ateru} koto ga dekireba kurithikaru hitto

こんこ比率の“点”に攻撃を当てることができればクリティカルヒット

If [I] manage {to land an attack at the "point" of this ratio}, [it]'s a critical hit.

- Context: a dog appears!

- wan' wan'

ワンッワンッ

Woof woof! - gurururu...

グルルル・・・

Grrr... - dekee!!

でけぇ!!

[It] is huge!- Relaxed pronunciation of dekai でかい.

- Symbols: focus lines, realization mark.

- kono deka-sa wa... kuma ka!!

このデカさは・・・クマか!!

This huge-ness... [it] is a bear?!!

This size... a bear?!!- In the sense of, with this size, this animal must be a bear! It's the only logical conclusion!

In games, it's common for the abilities of a character to be quantified in skill points or something like that, in which case the sa-form may be used. For example, like this:

| Adjective | Noun |

|---|---|

| tsuyoi 強い Strong. |

tsuyosa 強さ ?Strong-ness. Strength. |

| hayai 速い Quick. |

hayasa 速さ Quickness. Speed. |

| kashikoi 賢い Wise. Clever. |

kashikosa 賢さ ?Wise-ness. Wisdom. |

| un ga ii 運がいい [Whose] luck is good. [Who] is lucky. |

un no yosa 運の良さ The goodness of [their] luck. How lucky [they] are. Luck. |

There are mainly 3 ways to use the sa-form:

- To say something has a lot of a certain quality.

- To say something doesn't have as much of a quality as you expected.

- To compare how much of a quality something has to how much something else has of that quality.

In the first case, if you're talking about "the X-sa of something," that implicates both that:

- Something is X. (something has this X quality.)

- Something is very X. (something has a lot of this X quality.)

For example, if we say:

- yuki no shiro-sa

雪の白さ

The whiteness of snow.

How white the snow is.

That implicates:

- yuki ga shiroi

雪が白い

The snow is white. - yuki ga totemo shiroi

雪がとても白い

The snow is very white.

After all, if it weren't notably white, we wouldn't be talking about how white it is.

This is important since, for example, with measurements, there are antonym adjectives that are also positive, like:

- karui

軽い

Light. (antonym of heavy.)

- Not to be confused with usui 薄い, "light (color)," "thin," as in low concentration, antonym of koi 濃い, "deep (color)," "thick," as in high concentration.

- mijikai

短い

Short. (antonym of long.) - hikui

低い

Low. Short. (antonym of high, tall.)

Both something karui, "light," and something omoi, "heavy," have a positive "weight," juuryou 重量. After all, nothing can have a negative weight—you can't weigh negative kilograms. The difference is that something "light" has LITTLE weight while something "heavy" has MUCH weight.

The sa-form can emphasize the quantity of a quality, but in this case we aren't talking about "how much weight" something has, instead, we're talking about "how much LITTLE-weight" something has with karu-sa, and "how much MUCH-weight" something has with omo-sa.

- karu-sa

軽さ

The lightness [of something].

How light [it] is.

How little [it] weighs. - mijika-sa

短さ

The shortness [of something].

How short [it] is.

How small [its] length is. - hiku-sa

低さ

The lowness [of something].

How low [it] is.

How vertically-challenged [it] is.

The second case can be seen in sentences like:

- surudo-sa ga tarinai

鋭さが足りない

The sharp-ness of [it] isn't sufficient.

It isn't sharp enough.- surudoi

鋭い

To be sharp. (as in a blade, a knife, or a person of sharp mind.)

- surudoi

And lastly there are also sentences like:

- haya-sa nara makenai

速さなら負けない

If [it] is quick-ness, [I] won't lose.

If it's about speed, about how quick one is, I won't lose. (because I'm faster than everybody else.)

For reference, some other examples:

- Context: Akkun あっくん, who doesn't have friends, makes his first friends.

- genki...... dashite kudasai ne?

元気・・・・・・出して下さいね?

[Cheer up,] okay? - yoshi yoshi

よしよし

[There there]. - yokatta nee Akkun

よかったねーあっくん

[Isn't that great,] Akkun. - nadenade

なでなで

*pat pat*

- naderu

撫でる

To pat. To caress. - See also: head pat.

- naderu

- ...yasashisa ga tsurai...

・・・優しさがつらい・・・

...kindness [hurts]...- sono hito ga yasashii

その人が優しい

That person is kind. - sono hito no yasashisa

その人の優しさ

The kindness of that person.

- sono hito ga yasashii

- Context: Harima Kenji 播磨拳児 is about to get violent.

- ima sara kono ore-sama no osoroshi-sa ni kidzuite-mo oso-sugiru ze...?

今さらこの俺様の恐ろしさに気づいても遅すぎるぜ・・・?

?Even if [you finally] noticed my terrifying-ness, it's [already] too late.

Even if [you finally] noticed how terrifying I am, it's [already] too late.- sono hito ga osoroshii

その人が恐ろしい

That person is terrifying. Frightening. - sono hito no osoroshi-sa

その人の恐ろしさ

?That frightening-ness of that person.

How frightening that person is. - ima sara

今更

Only now. After all this time. Finally. - kidzuku

気づく

To notice. - kidzuite-mo

気づいても

Even if [you] notice. - osoi

遅い

Late. - oso-sugiru

遅すぎる

Too late.

- sono hito ga osoroshii

- Context: a war starts about "fried rice," chaahan 炒飯.

- See also: salt bae.

- {{{tamago to kome wo mazete} itameru} dake toiu} shinpuru-sa yue ka otoko no te-ryouri toshite wa {pasuta ni narabu} ninki wo hokoru!

卵と米を混ぜて炒めるだけというシンプルさ故か男の手料理としてはパスタに並ぶ人気を誇る!

[Perhaps because of] the simplicity [of] {just {{mixing eggs and rice} and then frying [it]}, [it] boasts a popularity [that] {rivals pasta} as a guy's cooking!- sono ryouri ga shinpuru da

その料理がシンプルだ

That cooking is simple.

That dish is simple. - sono ryouri no shinpuru-sa

その料理のシンプルさ

The simple-ness of that cooking.

The simplicity of that dish.

How simple that dish is. - This sentence says that, because men can't cook, they prefer dishes that are easy to make, such as pasta, and fried rice is so simple to make that its popularity among guys as a dish choice rivals that of the pasta.

- narabu - "to be side by side with [something]," "to line up with [something]," "to queue," "to rival in rank," "to be shoulder to shoulder with."

- te-ryouri - literally "hand cooking," refers to cooking done by a person privately, rather than a cook professionally.

- sono ryouri ga shinpuru da

- ~~daga shinpuru nagara tsukuri-kata wa {hito ni yotte} sama-zama

ーーだがシンプルながら作り方は人によって様々

However, while simple the ways-to-cook [it] vary {from person to person}.

The Lack Of

The sa-form of nai 無い, "nonexistent," translates to "the lack of."

- okane ga aru

お金がある

Money exists.

There is money.

[I] have money. - okane ga nai

お金がない

Money is nonexistent. Money doesn't exist.

There isn't money.

[I] don't have money. - okane no nasa

お金のなさ

The nonexistentialness of money.

How much money doesn't exist.How little money exists.

The lack of money.

How much [I] don't have money. How much little money [I] have. How much [I] lack money.

This only applies to the main adjective nai 無い. When ~nai ~ない is an auxiliary adjective (hojo-keiyoushi 補助形容詞), it won't translate to "the lack of," since it won't have the nonexistent meaning.

- jinjou da

尋常だ

[It] is normal.- Not having anything ijou 異常, "abnormal."

- futsuu 普通 is "normal" in the sense of "typical," "common," i.e. not unusual.

- jinjou janai

尋常じゃない

[It] isn't normal. - jinjou jana-sa

尋常じゃなさ

The non-normalness [of it].

How non-normal [it] is.

How abnormal [it] is. The weirdness [of it].

When ~nai ~ない is a jodoushi 助動詞 suffixed to verbs, it lacks an aru ある counterpart and lacks a sa-form as well.

- wakaranai

わからない

[I] don't know. - *wakara-aru

わからある - *wakarana-sa

わからなさ

Although this last ~nai can be conjugated like an i-adjective, the fact that it lacks a sa-form is evidence that it isn't really an adjective but a verb that looks like an adjective instead. Conversely, the nai that replaces aru in negative sentences has a sa-form, which means it's not simply an irregular conjugation of the verb aru, but an actual adjective.

vs. How Much

The sa-form doesn't mean the same thing as "how much" in English. For example, it's not normal to ask "how much" something is with te sa-form. Instead, you'd see phrases like this:

- ikura?

いくら?

How much is [it]?

How much does it cost? What's the price of this thing?

What's your price? (used when bribing people.)- ikura demo harau

いくらでも払う

[I] will pay however much [it] is. I'll pay any price.

- ikura demo harau

- dore dake?

どれだけ?

Which quantity? (literally)

How much?- {dore dake benkyou shitemo} wakaranai

どれだけ勉強してもわからない

[I] don't understand [it] {no matter how much [I] study}.

- {dore dake benkyou shitemo} wakaranai

- hyaku-guramu tte dore kurai?

100グラムってどれくらい?

How much is one hundred grams?- In the sense of how much is that quantity, e.g. it's one cup, one spoon, etc., not in the sense of how much it costs.

- dore hodo jikan ga kakaru?

どれほど時間がかかる?

How much time does [it] take?

The sa-form refers to a quantity, and the interrogative pronouns above also refer to quantities. It's possible to use both in a question to ask how much of a sa-form quantity something has. For example:

- omo-sa wa dore kurai?

重さはどれくらい?

The heaviness is how much? (literally.)

How much does it weigh?

How heavy is it?- omo-sa wa nan-kiro?

重さは何キロ?

How many kilograms is the heaviness?

- omo-sa wa nan-kiro?

- naga-sa wa dore kurai?

長さはどれくらい?

The longness is how much? (literally.)

How long is it?- naga-sa wa nan-senchi?

長さは何センチ?

How many centimeters is the longness?

- naga-sa wa nan-senchi?

vs. ~み

Another way to create nouns from adjectives in Japanese is through a ~mi ~み suffix (called mi-kei ミ形, or mi-meishi み名詞). The difference between ~sa and ~mi is that ~mi refers to the feeling the presence of quality elicits in you rather than its quantity. For example:

- omomi

重み

The feeling of weight that something gives. - X wa omomi ga aru

〇〇は重みがある

X has omomi.

In the sentence above, we're saying something has omomi, that is, that it feels like it's "heavy," omoi, that it has weight.

If we said the opposite, omomi ga nai 重みがない, "[it] doesn't have omomi," that wouldn't mean the thing weighs zero kilograms, it would mean it doesn't give you the feeling of weight that you expected it to have.

For example, if you buy a device that feels too light, it feels cheap as if it were made out of plastic, while one that feels heavy, feels like it has a higher quality because it's made of metal or something like that.

The usage of this suffix is very limited, and in many cases it's not even certain that the suffix is actually being attached to an adjective. Observe the words below:

- tanoshii

楽しい

Fun. - tanoshimu

楽しむ

To enjoy [something]. - tanoshimi

楽しみ

The enjoyment of [someone].

[Something] that [someone] enjoys. - kanashii

悲しい

Unfortunate. Sad. - kanashimu

悲しむ

To feel saddened by. - kanashimi

悲しみ

The sadness of [someone].

In the examples above, we have an i-adjective (tanoshii/kanashii), and a godan verb ending in ~mu (tanoshimu/kanashimu), which share the same stem (tanoshi~/kanashi~).

It's possible that tanoshimi comes from the adjective tanoshii plus the ~mi suffix, but it's also possible, and in fact far more likely, that it's the ren'youkei 連用形 (which changes the vowel to ~i) of the verb tanoshimu. Compare with another ren'youkei:

- odoru

踊る

To dance. - odori

踊り

The dance of [someone].

Every dance has someone that dances it, and every sadness has someone that feels it. It's the same idea, so it must be the same form.

But not all ~i/~mi word pair stems have also a derived ~mu verb.

There's wakai 若い, "young," and wakami 若み, which is when there's a feeling of youthfulness in someone, but there's no wakamu verb.

There's amai 甘い, "sweet," and amami 甘み, which is when there's feeling of sweetness in something, but there's no amamu verb.

In these cases, the mi-noun can't be the ren'youkei of the mu-verb, because there's no mu-verb, so it must be the i-adjective plus the ~mi suffix.

One last cool case is that you may have heard of the word umami, which is one of the five basic tastes, and you may have heard of the word umai うまい, which means "delicious," so you may be expecting umami to be umai with the ~mi suffix, but it isn't: the ~mi morpheme of umami 旨味 just means "taste," like in mikaku 味覚, "sense of taste," so and the word umami would mean literally "delicious taste." The other tastes are:

- kanmi

甘味

Sweetness. "Sweet taste." - sanmi

酸味

Sourness. "Acid taste." - enmi

塩味

Saltiness. "Salt taste." - nigami

苦味

Bitterness. "Bitter taste."

vs. ~度

A morpheme that works similar to ~sa ~さ is ~do ~度, "degree of." For example:

- toumei da

透明だ

[It] is transparent. - toumei-sa

透明さ

[Its] transparency-ness.

How transparent [it] is. - toumei-do

透明度

[Its] degree of transparency.

How much transparent [it] is.

The difference between these two morphemes is that ~do ~度 can only be used with measurable, quantifiable qualities, and that it doesn't have the "very" implicature that ~sa has.

For example, if we say:

- sabaku no atsu-sa

砂漠の暑さ

The hot-ness of the desert.

How hot the desert is.

It's implicated that the desert is "very" hot, or notably hot for some reason. On the other hand, if we said:

- sabaku no ondo

砂漠の温度

The temperature of the desert.

Then we're only talking about the measurement, without implicating there's anything exceptional or noteworthy about it.

Similarly, toumei-sa is typically used in cases where the transparency of something is notable—wow, look at how transparent this thing is!—while toumei-do is used in any case where the transparency is measurable—it's 42% transparent.

- By the way, "opacity," the antonym of transparency as used in image editing software, would be called fu-toumei-do 不透明度, "degree of non-transparency," or "how much not-transparent (opaque) something is."

No comments: