In Japanese, parentheses (), are used in multiple ways: they can show the age, gender or other personal information after someone's name; they represent furigana 振り仮名 (ruby text) in single-line layouts; on the internet, they contain emotes, such as "lol," etc.; they similarly enclose actions in theatrical scripts; they may contain thoughts or other comments; and they surround optional phrases or alternative phrases in grammatical examples.

In Japanese

To say "parentheses" in Japanese:

- maru-kakko

丸括弧

Round brackets. - shou-kakko

小括弧

Small brackets. - paaren

パーレン

Parentheses.

As for occurrence:

| Term | Hits |

|---|---|

| パーレン | 8 |

| 丸括弧 | 3 |

| 丸カッコ | 4 |

| 小括弧 | 1 |

| 小カッコ | 0 |

To say "open parenthesis" and "close parenthesis," the word for brackets, kakko, is used instead, due to the parentheses being round brackets.

- hajime-kakko

初め括弧

Starting bracket. Opening bracket. - owari-kakko

終わり括弧

Ending bracket. Closing bracket. - kakko-hiraki

括弧開き

Opening a bracket. Open bracket. - kakko-toji

括弧閉じ

Closing a bracket. Close bracket. - kakko-hiraki something kakko-toji

括弧開き〇〇括弧閉じ

Open bracket, something, close bracket.

Open parenthesis, something, close parenthesis. - kakko something kakko-toji

括弧〇〇括弧閉じ - kakko something

括弧〇〇

After Name

Age

A number in parentheses after someone's name in Japanese typically indicates their age, e.g. "John (30)" means John is 30 years old. This is frequently seen in news articles, but you can also find it in manga and anime when a character is introduced.

- Context: Akaza Akari 赤座あかり, a 13 years old girl, regrets not being 14 years old like her friends, because they started middle school one year before her, so she spent a whole year without going to school with them.

- aaa...

あーあ・・・

Aah... (sigh.) - Akari ga {mou ichinen hayaku} umaretetara dougakunen datta noni

あかりがもう一年早く生まれてたら同学生だったのに

If Akari had been born {one year sooner} [we] would have been in the same year of school.

- Akari uses her own name as first person pronoun.

- umaretetara - contraction of umarete-itara 生まれていたら.

- Akaza Akari (juu-san)

赤座あかり(13)

Akaza Akari (thirteen).

Anime: Morita-san wa Mukuchi 森田さんは無口 (Episode 1)

- Context: Mayu Morita is 16 years old according to the parentheses after her name.

- See Japanese Writing Direction for other examples of mixed writing orientation.

- See Beta Eyes for her eye type.

Some series use abbreviated school years (高1, 中2, 小3, etc.) instead of explicitly writing how many years old a character is.

Personal Information

Gender, marital status, and other personal information may also be written in parentheses. This information is generally irrelevant—I mean, so is age, but this is even more irrelevant—so it's typically only found in the rare cases where it matters for some reason.

- Tarou (dokushin)

太郎(独身)

Tarou (unmarried).

Gender

Gender is expressed by either the kanji of otoko 男, "man," and onna 女, "woman," or the symbols for the planets "Mars," Kasei 火星 and "Venus," Kinsei 金星, which are ♂ and ♀, respectively.

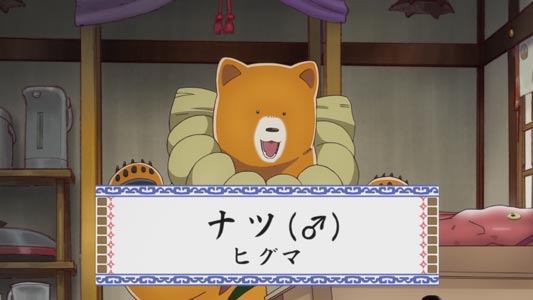

Anime: Kuma Miko くまみこ (Episode 1)

- Context: a character is introduced.

- Natsu (♂)

ナツ(♂)

Natsu (male.) - higuma

ヒグマ

Brown bear (Ursus arctos.)

Furigana

Main article: furigana 振り仮名.

The parentheses may also show the furigana, also called ruby text, which are normally reading aids showing how to read a kanji 漢字. The furigana is normally written in a smaller font side in a secondary line besides the base text it annotates. When this layout isn't possible, parentheses are used.

- kanji (kanji)

漢字(かんじ)

Chinese characters.- Here, ka-n-ji かんじ is the furigana in hiragana ひらがな showing how to read the kanji of the word kanji.

This always occurs on the internet, due to lack of support for the ruby layout in HTML and browsers. It may also occur in games.

Although manga targeted at children (shounen and shoujo manga) put furigana on basically every single word, no sane person is going to go around writing parentheses after every single word, or try to read such abomination of text.

Instead, the parenthetical furigana is generally limited to:

- Words being defined, e.g. in a dictionary, glossary, or in a paragraph about a term.

- Names of people and characters.

- Unusually difficult to read words, which the author insists in writing with kanji.

- Creative usage, i.e. gikun 義訓, in which the furigana isn't a standard reading for the kanji, but something else entirely, e.g.:

- (ekusukaribaa) seiken

聖剣(エクスカリバー)

(Excalibur) Holy sword.- Here, a word is pronounced "Excalibur," but spelled as "holy sword."

- (koko) chikyuu

地球(ここ)

(Here) Earth.- In this case, a word is pronounce "here," but spelled as "Earth," meaning that by "here" we're referring to the Earth, this whole planet, as opposed to only this country, or this city, or this tiny area around me, etc.

- (ekusukaribaa) seiken

- Context: Kokurase is a game made using RPGMaker, a tool that doesn't support ruby text, consequently, it uses parentheses to display the furigana for the names of the characters when introducing them.

- The game's first episode game is available for free on Steam.

- joshi seito

女子生徒

Female student.- Games made with RPGMaker tend to write the name of the character speaking as the first line in the dialogue box, probably because the tool doesn't come with a way to display the name of the character in a separate box.

- I don't want to diss the software or anything, but the way RPGMaker is designed is a nightmare. The text shown on these dialogue boxes is inputted in a field that's displayed as-is. There's no automatic line-wrapping. It's fixed to four lines of height. And it must use monospaced fonts in order for the text in-game to have the same size as the text in the editor, WYSIWYG-style, otherwise it will just not fit in the dialogue box.

- This hellish design is only tolerable because its main target audience speaks Japanese. You see, in Japanese a single character can be an entire word, so the fact you literally can't fit more than around 20 characters in a single line doesn't matter. It takes 4 spaces to say "female student" in Japanese: 女子生徒. In English, the same amount of space gets you "fema." Because the text must be monospaced due to cursed design reasons, it doesn't matter if "f" is half the size of 女 in most fonts, they both take the same number of pixels to display in that dialogue box. On top of that, English's syntax requires writing "I" and "you," whereas Japanese can omit the pronouns. Given this, the same dialogue box on which you can write a lot in Japanese, you can write very little in English, and if you sacrifice a whole line for the character name, you may not even be able to write a full sentence in English. Japanese RPGMaker games can say a full sentence with half line and break the line there, leaving half the box unused, empty, like some sort of space-squandering dialogue box baron. English RPGMaker games can't afford this spacious luxury and only wrap lines when they run out of space.

- Some games use descriptions like "student," "villager," etc. for nameless background characters, and, by extension, important characters who haven't been named yet, but will soon.

- Games made with RPGMaker tend to write the name of the character speaking as the first line in the dialogue box, probably because the tool doesn't come with a way to display the name of the character in a separate box.

- "watashi, Kamata Sakura wa

Koyasu Yoshimitsu-san ga suki"

「私、蒲田桜(かまた さくら)は、

子安洋光(こやす よしみつ)さんが好き」

"I, Kamata Sakura, like Koyasu Yoshimitsu."

- suki - "to like [something, someone]," "to love."

- 「」 - quotation marks.

Modern HTML has a <ruby> tag allows displaying text in a ruby layout. There's also a <rp> tag specifically to mark the parentheses.

If a browser doesn't support <ruby>, it won't treat the tag specially and show the whole text with parentheses. Browsers that support this feature will display text inside a <rt> tag as furigana, and hide the parentheses inside <rp> tags. For example, the following code:

<ruby>漢字<rp>(</rp><rt>かんじ</rt><rp>)</rp></ruby>

Results in かんじ above 漢字, and hides ( and ). The result:

- 漢字

Even if browsers support it, that doesn't mean editors do. If Twitter doesn't add the ability to write ruby text in tweets (and it probably never will), then it doesn't matter if browsers support the tag or not, you'll never see ruby text on Twitter, as users can't write it, and so parentheses will be used instead.

Weekday

Sometimes, a single kanji between parentheses may the weekday a date is on, or rather, the abbreviation of the weekday.

- (nichi)youbi

(日)曜日

(Sun)day. - (getsu)youbi

(月)曜日

(Moon)day. Monday. - (ka)youbi

(火)曜日

(Mars) day. Tuesday. - (sui)youbi

(水)曜日

(Mercury) day. Wednesday. - (moku)youbi

(木)曜日

(Jupiter) day. Thursday. - (kin')youbi

(金)曜日

(Venus) day. Friday. - (do)youbi

(土)曜日

(Saturn) day. Saturday.

Action Tags

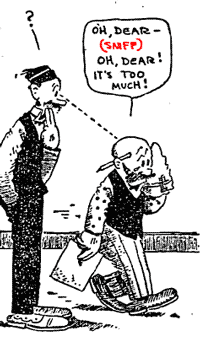

In theatrical scripts, since the text is mainly what the characters say, parentheses may enclose an action the character is supposed to do, physically, such as laughing.

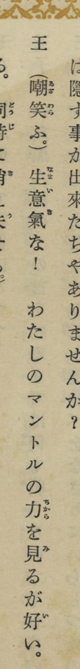

Author: Akutagawa Ryūnosuke 芥川龍之介

Published: Year 3 of the Shouwa 昭和 era, a.k.a. 1922. (see years and eras.)

Source of the image: 三つの宝 - 国立国会図書館デジタルコレクション - dl.ndl.go.jp, accessed 2019-03-22.

The book in plain text, slightly different: 三つの宝 芥川龍之介 - www.aozora.gr.jp, 2019-03-22.

- ou (aza-warafu.) namaiki na! watashi no mantoru no chikara wo miru ga ii.

王 (嘲笑ふ。)生意気な! わたしのマントルの力を見るが好い。

King: (sneers.) naive, [aren't you]! [You shall] see the power of my mantle!- warafu

笑ふ

Ancient pronunciation of warau 笑う, found in "classical literature," kobun 古文. This book isn't all that ancient, though, so it's probably just this character, a "king," that speaks in this ancient way. - See also: why is ha は pronounced wa? Particles he へ as e, wo を as o?

- warafu

Thoughts

In light novels, games, specially JRPGs, part of a character's dialogue enclosed by parentheses is a thought, an internal, mental monologue, what the character is thinking, literally. This is equivalent to thought bubbles in manga.

In novels, spoken lines are normally enclosed by 「」 or 『』, the quotation marks. In games with text dialogue, a box shows up on the bottom or top part of the screen with the character's lines.

Novels have more freedom to describe a character's thoughts, so they don't really need to use parentheses. Games, on the other hand, are limited by the dialogue box format, so they rely on parentheses to symbolize thought.

- If a line starts with 「 , it's what a character says.

- If a line starts with (, it's what a character thinks.

- Otherwise, it's probably a textual description of what is happening.

On The Internet

In Japanese net slang, parentheses at the end of a sentence may include either an action (emote) or a remark on a quote, often as a joke. These two uses are likely derived from the "action" and "thought" usage we've seen above.

- kakko-warai

(笑)

"(laugh.)"

LOL. - imi-shin

(意味深)

"(profound meaning.)"

Emotes

When parentheses express an emote, they may get read out loud as kakko かっこ, "bracket," like open round bracket, open parenthesis. For example:

- kakko warai kakko-toji

括弧笑い括弧閉じ

[Open] parenthesis, laugh, close parenthesis.- This is how you read out loud (笑).

- The kakko-toji, "close parenthesis," is often unnecessary, so it becomes kakko-warai.

Generally emotes omit okurigana 送り仮名 when in ren'youkei 連用形, e.g. warai 笑い, "laugh (noun)," gets spelled warai 笑 without the ~I ~い okurigana.

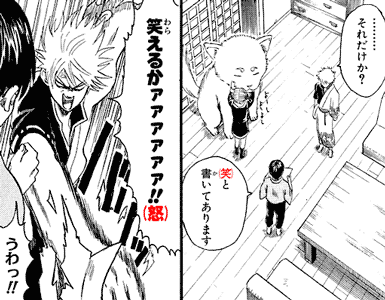

- Context: characters from Gintama do odd jobs. Someone left a monstrously huge dog outside their home, with a letter that said "please take care of my pet."

- ......... sore dake ka?

・・・・・・・・・それだけか?

.........only that? (that's all that is written?) - kakko-warai to kaite-arimasu

(笑)と書いてあります

(laugh) is [also] written. (literally.) - waraeru kaaaaaaa!! kakko ikari kakko-toji

笑えるかァァァァァァ!!(怒)

[How] can [I] laugh!! (anger)- waraeru - potential verb from warau 笑う, "to laugh."

- See also: tsukkomi ツッコミ.

- Although the manga makes no distinction, in the anime adaptation (10th episode), Shinpachi 新八 pronounces (笑) as kakko warai, without kakko-toji 括弧閉じ, "close [round] bracket," while Gintoki 銀時 pronounces (怒) as kakko ikari kakko-toji.

- uwa'!!

うわっ!!

This emote usage may be considered dated. For example, w's at the end of a sentence are typically used to say "lol" in Japanese instead of (笑)

The difference between these two uses tends to be that w's are perceived as more mocking, trolling, inflammatory laughing, like comparing "lol" with a smiley like ":D".

- sou da w

そうだw

That's right lol. - sou da kakko-warai

そうだ(笑)

That's right :D.

Some examples of emotes include:

Middle: Carrera Maaka, カレラ・マーカー

Right: Maaka Ren 真紅煉

Anime: Karin かりん (Episode 7)

- kakko-bakushou

(爆笑)

Explosive-laughter. (literally.)- See also: laughter lines.

- kakko-baku

(爆) - kakko-kushou

(苦笑)

Pained laughter. Bitter smile.

- kakko-namida

(涙)

Tears. - kakko-naki

(泣)

Crying.- naki 泣き, from naku 泣く, "to cry."

Anime: Hayate no Gotoku! ハヤテのごとく! (Episode 11)

Anime: Full Metal Panic, フルメタル・パニック! (Episode 9)

Anime: Nichijou 日常 (Episode 1)

Anime: Inu x Boku SS, 妖狐×僕SS (Episode 4)

Anime: Bonobono ぼのぼの (1995) (Episode 1)

- kakko-ase

(汗)

Sweat.- As in the sweat drops used in manga and anime.

- Generally for feeling under pressure, asette-iru 焦っている.

- kakko-akire

(呆)

Exasperation. Astonishment.- akire 呆れ, from akireru 呆れる, "to be astonished," often used when exhausted by the behavior of someone, "to be fed up."

- See also: sigh.

- kakko-ikari

(怒)

Anger.- See also: ikari-maaku 怒りマーク, "anger mark."

Speech Modes

In some cases, the text in parentheses doesn't refer to an emotion but instead describes how a sentence is uttered.

- (bou-yomi)

(棒読み)

Reading in monotone. (typically used when a character is so bad at lying that when they lie they become nervous and start speaking in monotone.)

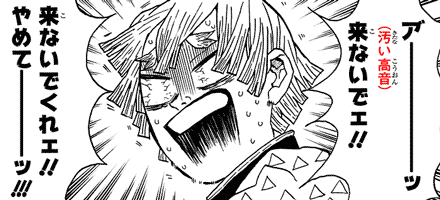

- Context: Agatsuma Zen'itsu 我妻善逸 runs away from an oni 鬼.

- a´~~' (kitanai kouon)

ア゛ーーッ(汚い高音)

Aahhhhh! (filthy high-pitched tone.)- The text in parentheses describes Zen'itsu's iconic, utterly obnoxious voice.

- konaidee!!

来ないでェ!!

Don't come!! (literally.)

Go away!! - konaide-kuree!!

来ないでくれェ!!

Please go away!! - yamete~~'!!!

やめてーーッ!!!

Stop!!!

Emotes in English

In English comics, parentheses have been used to represent actions, such as (sniff), (cough), (sigh), (gasp), (choke), (gulp), and so on.(languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu)

Image source: https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=4466, accessed 2021-08-30.

On the internet, in English, asterisks are typically used in similar fashion, except that, while the actions in parentheses in comics are in the infinitive, actions in asterisks are in third-person, present tense, perfective aspect, which normally only works with performative verbs used in first-person.

- *laughs*

Normally, sentences like "I promise," "I forgive," "I order you to," etc., have a verb in present tense (promise, forgive, order), which performs the action it describes as it's uttered, e.g. the act of saying "I promise" results in the making of a promise.

This only makes sense with a group of verbs that are said to be performative. After all, saying "I laugh" doesn't make me laugh.

Performative utterances don't work in third-person: if I say "he forgives you," I'm not making him forgive you by uttering the sentence, I'm saying he has forgiven you already.

However, in the textual medium, the narration within asterisks makes you imagine the action described in the asterisks. The action never occurs if it isn't uttered, and only occurs because it's uttered, so *laughs* *cries* *gasps* and so on end up being both performative and in third-person.

Likely, this occurs because there is no way to perform the action physically, such as crying, in an online chat in the virtual world for example, so the narration of the action substitutes its performance.

Or, in increasingly verbose language:

Users resort to typical terms that once [sic] can find in a dictionary as prototypical of the equivalent nonverbal behaviour. Therefore, they vary inter-culturally depending on the lexical repertoire that languages offer for the description of nonverbal behaviour.(John Benjamins, 2011:173, as cited in languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu)

Commentary

Parentheses at the end of a sentence may include some commentary remarking the sentence's meaning, which is mostly used to make jokes on the internet.

Anime: Tensei shitara Slime Datta Ken, 転生したらスライムだった件 (Episode 1)

- otoko (jishou)

漢(自称)

Man among men (self-proclaimed).

In particular, tweets on anime episodes often feature quotes from the show along with such remarks. For example:

- tetsugaku

哲学

Philosophy. (2deep4me without the snark.)

- Context: Japanese Twitter reacts to character questioning "what ARE maid clothes" in terrifyingly robotic fashion.

- meido-fuku to wa (tetsugaku)

メイド服とは(哲学)

[What are] maid clothes? (philosophy.)

- meido-fuku to wa - what the character said, literally.

- tetsugaku - what users added.

A common pair of such tags is:

- (imishin), or (imibuka)

(意味深)

Deep meaning.

Profound meaning.

- Used when a phrase sounds suggestive, like a double entendre. In practice, the phrase is sometimes not suggestive at all, and only becomes suggestive by suggesting it's suggestive, like adding an "...in bed" to a fortune cookie's message to make it sound funnier than it originally was.

- Apparently, an abbreviation of imi-shinchou 意味深長, "meaning profound," so it should be read imi-shin, but some people read it imi-buka instead, from fukai 深い, "deep," affected by rendaku 連濁.

- (imisen), or (imiasa)

(意味浅)

Shallow meaning.- The opposite of the above, typically used on a phrase that's obviously suggestive without context, but in the context it was used actually had the literal, non-suggestive meaning.

- The word imishin uses the on'yomi 音読み of 深, so if one were to match, this one would be pronounced imi-sen, but this sen reading of the 浅 kanji isn't as common as the shin one, so the kun'yomi 訓読み asa, from asai 浅い, "shallow," gets used instead

For example, there's a number of completely innocent words that are innuendos for "to have sex with" for some ungodly reason and they're absolutely going to show up everywhere:

- taberu

食べる

To eat [a food].- kare wo tabeta (imi-shin)

彼を食べた(意味深)

[She] ate him (profound meaning, i.e. figuratively). - kare wo tabeta (imi-sen)

彼を食べた(意味浅)

[She] ate him (shallow meaning, i.e. literally).

- kare wo tabeta (imi-shin)

- idaku

抱く

To hug.

To embrace. - gattai suru

合体する

To combine.

To fuse together.

To become one.- Often used in series with robots.

- nakayoku suru

仲良くする

To make peace. (in the sense of friends who got in a fight becoming friends again.)

It isn't hard to say any phrase containing such words is suggestive if your mind is in the gutter.

Manga: Senki Zesshou Symphogear XV, 戦姫絶唱シンフォギアXV (Episode 3)

- Context: an ago-piisu 顎ピース, "chin peace [sign]."

- It doesn't mean anything.

- In Japanese culture, at least.

An actual example:

俺は今日から猫になる(意味深) #uchitama pic.twitter.com/x52cPw7U2s

— たっくん (@n092t) January 16, 2020

- Context: a anthropomorphic bulldog falls in love with a cat girl, proclaims:

- ore wa kyou kara neko ni naru (imi-shin)

俺は今日から猫になる(意味深)

Starting today, I'll become a cat (profound meaning).- In Japanese, neko 猫 means "cat," while neko ネコ is a gay slang meaning the "bottom" in a relationship, as opposed to the "top," tachi タチ, so the profound meaning would be:

- "Starting today, I'll become a bottom."

In similar usage, sei-teki na imi de 性的な意味で, "with the sexual meaning [of the phrase]," and variants also exist.

- Context: Hanako 花子, a voracious dragon girl, wants to devour Shibata Genzou 柴田源蔵.

- itsu-ka Genzou-sama wo ajimi sasete wa moraemasen ka? (shokuyoku-teki na imi de)

いつか源蔵様を味見させてはもらえませんか?(食欲的な意味で)

Genzou-sama, someday won't [you] let [me] have a taste of [you]? (in the appetite sense.) - (sei-teki na imi de) ajimi ka......

(性的な意味で)味見か・・・・・・

(In the sexual sense) have a taste, huh...... - o, omae ga otona ni natte kara na?

お お前が大人になってからな?

A... after you become an adult, okay?

Another example:

- butsuri-teki ni

物理的に

Physically.- As opposed to figuratively, or magically.

- kowareru (butsuri-teki ni)

壊れる(物理的に)

[He] will break (physically, like snapping in two and turning into pieces, as opposed to break down mentally).

Besides such meme-level tags, commentary may also work like parenthetical thoughts, expressing how the person really feels, what they're thinking, their impression, as opposed to what they say, in a manner close to emotes, e.g.:

- (kawaii)

(かわいい)

[It/he/she] is cute. - (kanashii)

(悲しい)

[I] am sad. [It] is a pity.

The writer uses parentheses to separate internal and external dialogue as if they were a manga character with thought bubbles and speech bubbles, which, obviously, are both visible to the reader either way, so it's not like you're hiding anything by writing it in your thought bubble.

A funny evidence of this is that sometimes someone will say the same thing twice, once externally and once internally, between parentheses, because it means they thought out loud, or said literally what they were thinking, e.g.:

- Context: a character with large breasts appears, someone on the internet inevitably comments:

- dekai (dekai)

デカイ(デカイ)

[They're] huge ([they're] huge).

Alternatively, it may work like an anti-gikun: if writing a different word between parentheses creates a secondary meaning, then adding the same word in parentheses means it means what it means as-is.

Optional Text

Parentheses are sometimes used to enclose optional text. It's used when teaching grammar, for example. Observe:

- 太郎は頭(が)いい

The text above means が is optional and may be omitted.

- Tarou wa {atama ga ii}

太郎は頭がいい

{Good is true about head} is true about Tarou.

Tarou's {head is good}.

Tarou is smart. - Tarou wa {atama ga φ ii}

太郎は頭いい

Besides these, circles 〇〇, X marks ××, and triangles △△ are sometimes used as placeholders, e.g.:

- __-san

〇〇さん

Mr. __. - X-gatsu Y-nichi

〇月×日

Month X, day Y.- c.f.:

- juu-ni-gatsu ni-juu-go-nichi

12月25日

Month 12, day 25.

25th of December. (Christmas day.)

Alternatives

Parentheses with phrases separated by slashes mean each phrase is a possible alternative that can go in that position in the sentence. This, too, tends to be used when teaching grammar. For example:

- ugoka(naku/nai you ni) naru

動か(なく/ないように)なる

To stop moving. To become in a way that doesn't move.

- An eventivizer applied to the two possible negative forms of a habitual predicate.

- ugokanai

動かない

[It] doesn't move. - {ugokanaku} naru

動かなくなる

{[It] doesn't move} in the future. (basically.) - {{ugokanai} you ni} naru

動かないようになる

[It] will become {so [that] {[it] don't move}}.

[It] will become {in a way [that] {doesn't move}}.

[It] will stop moving.

A slash preceding the closing parenthesis means the last alternative is empty.

- kirei (da/desu/φ)

綺麗(だ/です/)

[It] is pretty.- Here, da, desu, and nothing (null) are copulas that translate to "is" in English.

- kirei da

綺麗だ

[It] is pretty. - kirei desu

綺麗です - kirei φ

綺麗

In Evangelion

For the record, the usage of parentheses in the titles of the movie series Evangelion only occurs in the English titles, so it probably has nothing to do with Japanese. This article will (not) help you understand Eva. For reference, the Japanese titles:

- wevangeriwon shin-gekijouban: jo

ヱヴァンゲリヲン新劇場版:序

Evangelion - New Movie-Version: Beginning. (literally.)

Evangelion: 1.0 You Are (Not) Alone. (English title.)- The title uses the archaic we ヱ character, and wo ヲ, which are pronounced identically to e エ and o オ used in the original version: Evangerion エヴァンゲイオン.

- gekijouban - "movie version," or "theatrical edition," is part of the title of many anime movies.

- wevangeriwon shin-gekijouban: ha

ヱヴァンゲリヲン新劇場版:破

Evangelion - New Movie-Version: Destruction.

Evangelion: 2.0 You Can (Not) Advance. - wevangeriwon shin-gekijouban: kyuu

ヱヴァンゲリヲン新劇場版:Q

Evangelion - New Movie-Version: Q.

Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo.- Wait, what.

- Q?

- Wha—what does this mean? Q???

- It's literally the katakanization of the English letter "Q," kyuu キュー.

- This doesn't mean anything.

- It doesn't mean anything!

- And I thought the English titles didn't make sense.

- shin evangerion gekijouban 𝄇

シン・エヴァンゲリオン劇場版𝄇

New Evangelion - Movie-Version 𝄇

Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time- This one uses the same Evangelion spelling as the original series.

- Can you see what that character after 劇場版 is? It looks like a square to me. I copy-pasted it. My computer literally can't display that thing.

- You know why? Because it's a bar line—music notation. Why is there even a bar line in the title of this thing. Maybe the Japanese title is all different from the others because nobody would know how to pronounce this symbol.

- It's like 銀魂゜, I guess.

- I mean, on the the Japanese Wikipedia there's actually an image of what it's supposed to look like (see: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Repeat_close.png), and if you see it, and you've been paying attention to every last detail about these titles—as if that's going to help understand anything—you'd realize that this bar line has two dots on the left side, stacked vertically, which is exactly like the the colon punctuation (:) which the other titles have after gekijouban, but this title doesn't have, which means that, at least in part, the reason for adding this symbol to the title was that it had two dots in it. That's it. That's about as much as I can figure out. Best of luck.

References

- The cyberpragmatics of bounding asterisks - languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu, accessed 2021-08-30.

No comments: