In semantic grammar, "stative verbs," in Japanese: joutai-doushi 状態動詞, are verbs that express states, making them similar to adjectives. They contrast with eventive verbs, which express events.

There are multiple definitions for stative verb in Japanese. See lexical aspects for details.

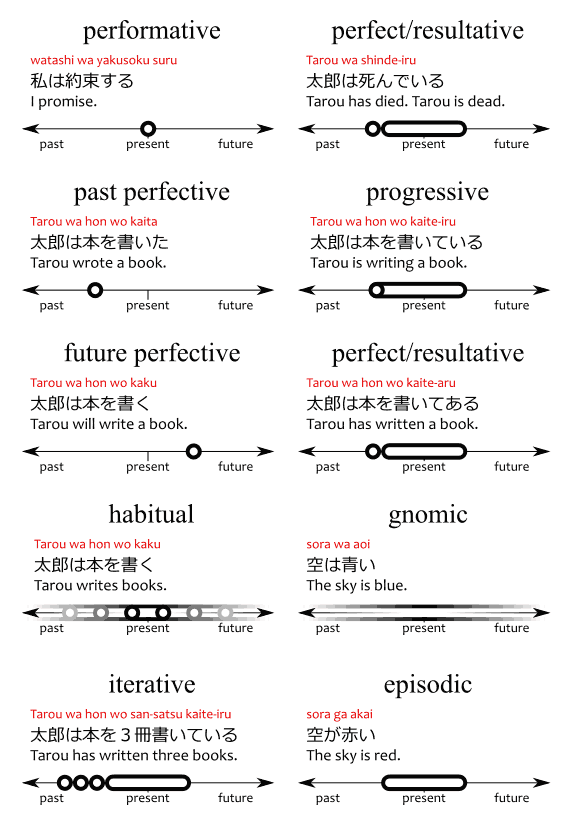

In Japanese, stative verbs used in nonpast form express a state in the present tense only, which is exactly how adjectives is nonpast form work. Observe the difference:

- Tarou wa manga wo yomu

太郎は漫画を読む

Tarou reads manga. (present habitual.)

Tarou will read manga. (future perfective.) - sora wa aoi

空は青い

The sky is blue. (present state.)

*The sky will be blue. (can't express futurity.) - minna wa sou omou

みんなはそう思う

Everybody thinks so. (present state.)

*Everybody will think so. (can't express futurity.

Above, the eventive yomu has both present and future tense, the i-adjective aoi only has present tense, and the stative verb omou only has present tense as well.

Grammar

In general, stative verbs can be identified by the fact that they typically appear in nonpast form in Japanese and in simple present in English, rather than appearing in the progressive in English, or in ~te-iru ~ている form in Japanese.

For example:

- Tarou wa manga wo yonde-iru

太郎は漫画を読んでいる

Tarou is reading a manga.

Above we have a verb in ~te-iru form, and the present progressive form, "is ~ing," in English. These two things are stativizers. They're necessary because events can't be observed in the present, only states can.

By contrast:

- banana to ringo wa chigau

バナナとリンゴは違う

Bananas and apples differ.

Bananas and apples are different.

Above we have the verb chigau in nonpast form, and "differ" in English in the simple present. It's not necessary to conjugate the verb to chigatte-iru 違っている, just like it's not necessary to say "is differing."

This happens because unlike yomu, chigau is a stative verb, so the state it expresses can be observed in the present.

A third situation are performative verbs, which make events occur in the present. For example:

- watashi wa yakusoku suru

私は約束する

I promise.

In English, performative verbs are stative.

- Tarou promises to do it.

In Japanese, however, they're eventive, so they require ~te-iru to be reported in the present.

- Tarou wa yakusoku suru

太郎は約束する

Tarou will promise. - Tarou wa yakusoku shite-iru

太郎は約束している

Tarou has promised. Tarou promises.

Not all statives are expressed through stative verbs. Notably, habituals are stative expressed through eventive verbs.

As you can see, there are discrepancies in what are stative verbs and what are eventive verbs in both languages. Fundamentally, however, the idea is the same, which is why there are also similarities between both languages.

Semantics

Semantically, states differ from events in that states don't occur, they're simply true, while events must occur at some point in time.

States require us to describe how something is, while events require us to describe what happened.

Consequently, events tend to be tangible, occurring physically and somehow observable, while states tend to be more abstract.

Syntax

Grammatically, stative verbs are states that are expressed in syntax through verbs, rather than through adjectives.

The reason for this tends to be a simple one: when a state can't be expressed through an adjective, it's expressed through a verb.

English adjectives can only predicate a single subject at a time.

Japanese, on the other hand, has double subject constructions, which allow a single adjective to directly predicate one small subject and indirectly predicate one large subject, resulting in a single adjective predicating two subjects at once.

Consequently, some English cognitive transitive stative verbs translate to Japanese as adjectives in double subject constructions. For example:

- Tarou wa {manga ga suki da}

太郎は漫画が好きだ

{Manga is liked} is true about Tarou.

Tarou {likes manga}. - Tarou wa {kumo ga kowai}

太郎は蜘蛛が怖い

{Spiders are scary} is true about Tarou.

Tarou {fears spiders}.

Above we have the verbs "likes" and "fears." We know they're stative because they're used in simple present. We know they're transitive because they take a direct object, manga and spiders, respectively. They're also cognitive, because they're about cognition, about thoughts.

Note that for such constructions the topic is often implicit when it's "me." Observe:

- watashi wa {manga ga suki}

私は漫画が好き

I {like manga}. - ∅ {manga ga suki}

漫画が好き

Stative verbs are generally transitive. It doesn't make sense for a state to become an intransitive verb, since in such case an adjective would be functionally identical as far as syntax is concerned. There are exceptions, however, such as the intransitive stative verb "exists."

- uchuujin wa sonzai suru

宇宙人は存在する

Aliens exist.

Future Tense

In Japanese, all statives, including stative verbs, can only express a future tense through futurates and eventivizers. Observe:

- Tarou wa kateru

太郎は勝てる

Tarou is able to win. Tarou can win.

*Tarou will be able to win. - ashita Tarou wa kateru

明日太郎は勝てる

Tomorrow, Tarou is able to win. (futurate.) - Tarou wa {{kateru} you ni} naru

太郎は勝てるようになる

Tarou will become {in a way that {is able to win}}. Tarou will be able to win.

Evidential Coercion

In English, a well-known theory about lexical aspect asserts that states don't occur in the progressive form(Vendler, 1957). In Japanese, a similar observation has been made about the ~te-iru form(金田一, 1950).

For instance, the stative verb "to know" isn't used in the progressive "is knowing." You don't say:

- *I'm knowing English.

Similarly, one doesn't conjugate the stative verb dekiru 出来る, "to be able to," to ~te-iru form.

The observations cited above have been shown to be incorrect, however.

In English, "stative verbs can be exceptionally used in the progressive form to indicate temporary state," for example(Freund, 2016:123, citing Quirk et al.,1985; Biber et al., 1999; Leech et al., 2009):

- George is loving all the attention he is getting.

Although the cognitive stative verb "to know" does resist the conjugation "to be loving," above we can see that another cognitive stative, "to love," is acceptable in the progressive. The same applies to "to be thinking."

In Japanese, stative verbs can also exceptionally be used in ~te-iru form to express a temporary state(adapted from 加藤, 2010:134–135):

- Tarou wa, ima no tokoro, chanto setsumei dekite-iru

太郎は、いまのところ、ちゃんと説明できている

Tarou, for now, has been able to explain it properly.- This phrase implies that, while Tarou has been able to explain it properly so far, it's uncertain whether he will able to explain the whole thing properly.

In both English and Japanese, a temporary property is expressed when a stativizer is used with an already stative predicate.

This sounds too convenient to be a mere coincidence. Surely, that must be a reason for this. Unfortunately, it's not a reason that's simple to explain.

For starters, it's important to know predicates are typically classified into three levels(Carlson, 1977):

- Stage-level predicates, or SLPs.

- Individual-level predicates, or ILPs.

- Kind-level predicates, or KLPs.

SLPs are distinguished from ILPs by the fact we can use SLPs in perception reports. For example:

- I see John drunk.

- This makes sense, therefore "John is drunk" is an SLP.

- *I see John student.

- This makes no sense, so "John is a student" isn't an SLP, it's an ILP.

ILPs are distinguished from KLPs by the fact that kinds are generalizations of individuals, and individuals are existential instances of kinds.

- Cats are cute.

- This means that, in general, cats are cute, so it's a KLP.

- It doesn't mean that all cats are cute, just that they generally are cute.

- These cats are cute.

- This means that, in particular, these cats are cute, so it's an ILP.

- It does mean that all of these cats are cute. There isn't a single non-cute cat among these!

Abstractions of entities and temporal occurrences are called generics(Krifka, 1995:3–4). A kind is an entity generalization, while a gnome is a temporal generalization over slices of time called episodes.

Just like KLPs are generally, but not necessarily always true, gnomic predicates are generally true, but not necessarily permanent. The opposite of a gnomic predicate is called an episodic predicate, which refers to a particular time.

In general, ILPs are gnomic, while SLPs are episodic, given:

that SLPs occur or hold crucially in space and time but that ILPs do not. [...] ILPs are properties of individuals and SLPs are descriptions of the world, or perhaps a spatiotemporal slice of it.(Fernald, 1999:51, citing Kratzer, 1988)

The English progressive displays properties of a SLP, in that it describes the world as it is right here and now. For example:

- John is drinking. (right here and now.)

- Means that "I see John drinking," or somehow perceive him so.

Naturally, this must mean that if I say "John is thinking," I must be able to perceive that John is thinking somehow. Similarly:

- John is silly.

- *I see John silly.

- This doesn't make sense, therefore, "John is silly" is an ILP.

- John is being silly.

- I see John being silly.

- This makes sense, therefore, "John being silly" is a SLP, or is it?

The phenomenon above is called "evidential coercion."(Fernald, 1999:54)

Basically, a predicate such as "is silly" is gnomic, in that it's assumed to be generally true. By contrast, if someone is "being silly," that doesn't mean they're generally silly. That means "being silly" isn't gnomic, it's episodic.

Since we can perceive someone being silly, it must occur physically, otherwise we wouldn't be able to perceive it, which means we have "evidence" that it occurs. If we perceive someone being silly here and now, that fits the definition of a stage-level predicate.

In Japanese, however, that doesn't seem to be the case.

Since SLPs describe the world, while ILPs describe individuals, it makes sense that the topic of an ILP would be the individual, while the topic of a SLP is the stage itself.

In Japanese, the topic is marked by the wa は particle or by the tte って particle. Since we don't utter "here and now" when talking about things we observe here and now, the stage topic is always implicit..

It's possible to tell SLPs apart from ILPs by the fact that SLPs normally won't have a marked topic, since the stage topic isn't uttered. SLPs will have a subject marked by the ga が particle instead.

This works pretty much like double subject constructions. Observe:

- sora wa aoi

空は青い

The sky is blue.- Gnomic ILP about the sky.

- ∅ {sora ga akai}

空が赤い

{The sky is read} is true about here and now.

[Here and now], {the sky is red}.- Episodic SLP about what we're seen right here and now, e.g. the sunset.

As we've seen previously, some predicates, like "student," don't make sense as SLPs since we can't perceive them. When they're used with the ga が particle nevertheless, they express a different function instead.

In summary, ga が has two functions: exhaustive listing and neutral description. They're about marking subject focus and sentence focus respectively, "focus" being the opposite of topic.

The one that works with SLPs is the sentence focus (i.e. neutral description)(鈴木, 2014:36), since when the whole sentence is focus, something not uttered must be the topic, and would be the stage. This is also known as the "news" ga が, as it's found in news headlines.

According to Sugita (2009:68–69), the ~te-iru form has four functions: "progressive," "perfective," and "experiential," "habitual." The first two functions display properties of a SLP, given ga が has the neutral description function with them, while the last two display properties of an ILP.

Sugita uses the term habitual based on Krifka, however, Krifka is about genericity, and there are reasons to believe that the "habitual" function of ~te-iru isn't generic, but episodic instead.

It's interesting to distinguish between gnomic and episodic pluractionality. The term habitual applies to gnomic, while iterative applies to episodic. When a habitual-looking predicates is limited by number of occurrences or period of time, it's iterative(Bertinetto & Lenci, 2010:4–6).

Given that the habitual, or rather, iterative ~te-iru displays properties of an ILP, we have a situation in which an ILP contains an episodic predicate, which makes it most likely the function responsible for evidential coercion in Japanese.

Presumably, the contradiction of an episodic predicate in an ILP has to do with whether the stage ranks as the top-level topic of the sentence or as a lower level implicit subject. For example:

- ∅ {ame ga futteiru}

雨が降っている

[Here and now], rain is falling from the sky. (literally.)

Rain is raining.

It is raining.- This is an SLP. The stage is the topic, while rain is a subject.

- watashi wa {∅ sou omotte-iru}

私はそう思っている

I, {[here and now], think so}.- This is an ILP. The topic is me, while the stage is a subject.

- The verb omou 思う is a cognitive stative, so its ~te-iru form is an instance of evidential coercion.

Above, the first example talks about things of a stage, while the second talks about a stage of an individual.

If English works like Japanese, then "I'm thinking," "I'm loving," "I'm being able to," etc. would be ILPs too.

Then again, it could be that this only happens in Japanese because we're just taking a gnomic predicate and making it episodic through ~te-iru, so the rest of the predicate doesn't change. Observe:

- Tarou wa {manga ga yomeru}

太郎は漫画が読める

{Manga is readable} is true about Tarou.

Tarou {is able to read manga}. (gnomic.) - Tarou wa {∅ {manga ga yomete-iru}}

太郎は漫画が読めている

{{Manga is readable} is true about here and now} is true about Tarou.

Tarou {[here and now] {is being able to read manga}}.

Types

There are several types stative verbs in both English and in Japanese.

In both languages, statives never express a dynamic activity, only something abstract that doesn't take place physically. Given this, stative verbs are sometimes called "static verbs," and eventive verbs get called "dynamic verbs" instead.

Unfortunately, although it appears that pretty much very English eventive verb is dynamic, the same isn't true for Japanese verbs, so the stative-eventive dichotomy is more accurate.

Existential

The most special type of stative verb are existence verbs. In Japanese, they would be aru ある and iru いる.

- mirai ga aru

未来がある

The future exists.

There is a future.

Note that aru ある is an irregular verb and its negative form is nai 無い.

- mirai ga nai

未来が無い

The future doesn't exist.

There is no future.

Existence verbs are special because they entail that the subject is existential and not abstract. For example, if I say:

- ningen wa kangaeru

人間は考える

Humans think.

Then that's a kind-level predicate, and the kind "humans" is abstract.

For example, imagine if we're aliens in a classroom learning about planet Earth, which was destroyed long ago. The teacher could say "humans think, but plants don't think." This sentence would make sense event under the assumptions humans don't exist.

It's not possible to use an abstract kind in a predicate that requires something existential, consequently, aru doesn't translate to "exist" when dealing with kinds. Observe:

- kuruma ga aru

車がある

*Cars exist. (wrong.)

There is a car. (correct.)

In cases such as the above, sonzai suru 存在する is used instead.

- kuruma wa sonzai suru

車は存在する

Cars exist.

Similarly:

- hito ga iru

人がいる

*People exist. (wrong.)

There is a person. There's somebody there. (correct.)

Note that there are variants of existence verbs that function exactly the same way:

- oru

おる

A polite (teineigo 丁寧語) variant of iru いる. - irassharu

いらっしゃる

A respectful (sonkeigo 尊敬語) variant of iru いる. - gozaimasu

ございます

A polite (teineigo 丁寧語) variant of aru ある.

Also note that there's an iru いる that means "to need," which is also stative, but it's not existential.

- shujutsu niwa {okane ga iru}

手術にはお金がいる

{Money is necessary} is true for the surgery.

The surgery {requires money}.

Copulative Constructions

The verb aru ある is found in several copulative constructions which are all stative and can all be understood existentially.

For example, de aru である, "is," and dewanai ではない, "is not," from which come the abbreviations da だ and janai じゃない. These are used predicatively with nouns and na-adjectives.

- wagahai wa neko de aru

吾輩は猫である

I'm a cat. - kirei de aru

綺麗である

[It] is pretty.

Syntactically, the de で above is analyzed as the te-form of the da だ copula, which makes it a ren'youkei 連用形. The verb aru is a hojo-doushi. That is, it's the same syntactical structure as the ~te-aru and ~te-iru forms.

The same construction is also seen in i-adjectives:

- kawaikunai

可愛くない

[It] is not cute.

Above, ~ku is the ren'youkei and nai is the negative form of the hojo-doushi aru. It's possible to insert the wa は particle just like with de wa では to form ~ku wa ~くは.

- kawaiku wa aru ga

kirei de wa nai

可愛くはあるが

綺麗ではない

Cute, [it] is, however,

pretty, [it] is not.

Stativizers

The ~te-iru ~ている form and the ~te-aru ~てある form make use of the existence verbs iru いる and aru ある as auxiliary verbs, specifically hojo-doushi 補助動詞. Consequently, these forms are also stative.

They can't be used with kinds(Sugita, 2009:256). That means they're also existential. Observe:

- hiiroo wa hito wo tasukeru

ヒーローは人を助ける

Heroes help people.- Abstract, we're talking about the concept of a hero, so this sentence doesn't requires heroes to actually exist.

- hiiroo wa hito wo tasukete-iru

ヒーローは人を助けている

Heroes are helping people.

- Existential, there must be a hero somewhere in order for this whole helping thing to be happening.

The ~te-iru and ~te-aru forms add an existential property to the predicate through evidential coercion, and, consequently, they can't be used with predicates that already possess this existential property.

It's not possible to use these forms with the existence verbs aru and iru, since they can already express something is existential by themselves:

- *atte-iru

あっている - *ite-iru

いている.

Similarly, it's not possible to use them with adjectives, since they can be used to express something is true here and now, which means it must exist here and now:

- *kirei de atte-iru

綺麗であっている

- Note that atte-iru あっている may also be:

- atte-iru

合っている

To be matching. - Which is a different verb: au 合う, "to match."

- *kawaiku atte-iru

可愛くあっている

With exception of the above, it's theoretically possible to conjugate all verbs to ~te-iru, since there should be no semantic rule that forbids it.

In practice, many verbs are never conjugated to ~te-iru form since that form makes no sense with the meaning of the verb, just like "I'm knowing" is unusual.

Potential

Japanese has several types of verbs that express the capability of doing something or of something happening. These potential predicates are all stative.

- yomeru

読める

To be able to read.- A "potential verb," kanou-doushi 可能動詞, derived from the godan verb yomu 読む, "to read."

- taberareru

食べられる

To be able to eat.- The "potential form," kanoukei 可能形, derived from the ichidan verb taberu 食べる, "to eat."

- tabereru

食べれる

- A variation called ra-nuki-kotoba ら抜き言葉.

- ari-eru, ari-uru

ありえる, ありうる

Possible to occur.- Expresses that aru ある is possible.

- ~dekiru

~できる

Able to.- The potential of suru する, used with suru-verbs.

Note that dekiru できる has multiple meanings. When it's used as the potential variant of suru, it's stative, but when it's used to say what something is made out of, it's eventive. Observe:

- karada wa tsurugi de dekite-iru

体は剣でできている

[My] body is made out of swords.- Here, dekiru is eventive.

- sonna koto mo dekiru?

そんなこともできる?

[You] can do even something like that?- Here, dekiru is stative.

Perceptual

Verbs that assert what is being perceived right now are stative. Asserting that something is perceived entails that it can be perceived, i.e. if you hear something, that must mean you can hear it.

- watashi wa {yuurei ga mieru}

私は幽霊が見える

{Ghosts are seen} is true about me.

I {can see ghosts}. - ∅ {ame no oto ga kikoeru}

雨の音が聞こえる

{The sound of hair is heard} [is true about me].

[I] {can hear the sound of rain}.

Such verbs are sometimes called copulative perception verbs.

They're said to be copulative in English because they link the subject to a complement describing a property of the subject. Notably, this complement is an adjective(Taniguchi, 1997:271, citing Quirk et al. 1985:54).

Below, the word "awful" is an adjective in all three cases, and it's the complement for the subject "it."

- It is awful.

- It seems awful.

- It tastes awful.

By contrast, non-copulative verbs, although appearing to be syntactically identical, can't actually be followed by adjectives. If you use a lexical adjective with it, it's parsed as a noun somehow.

- I know awful.

- Here, "awful" is a noun, since it refers to the concept of awful.

- In a copulative sentence such as "I look awful," the word awful is a property of me, it qualifies me.

- In a non-copulative, "I know awful," the word awful doesn't qualify me, so, syntactically, we don't have an adjectival complement, even though, morphologically, the word "awful" is a lexical adjective.

In English, copulative perceptual stative verbs include, for example(Taniguchi, 1997:270–271):

- It seems. It looks. [It appears.]

- It tastes.

- It smells.

- It sounds.

- It feels.

Note: "to become" is a copulative verb, too, but it's not stative.

These verbs and its Japanese counterparts share several similarities, given that at a semantic level what they attempt to convey is the same thing, but also have differences in syntax.

To begin with, reality and our perception of reality are different things, and anyone who has lived enough some years in reality already knows that sometimes things aren't what they seem.

In Japanese, there are two ways to say "seems" and "sounds."

The first one is used when the speaker assumes that what they perceive is true, while the second one is used when the speaker considers the possibility it's false, or when they're contrasting what they assume to be true with how something is perceived.

In the first case, "seems" and "sounds" translate to the sou そう suffix, which is conjugated as a na-adjective.

- ita-sou da!

痛そうだ!

[It] seems painful!

[It] sounds painful!- This sentence can be used even if something isn't actually painful, it just seems to be painful.

In the second case, "seems" and "sounds" translate to kikoeru and mieru.

Syntactically, kikoeru and mieru work the same way as naru: they take the complement as an adverb.

- semaku mieru

狭く見える

[It] looks cramped. (~ku adverbial form.)- Could imply something is objectively spacious, but feels cramped for that person.

- uso ni kikoeru

嘘に聞こえる

[It] sounds untruthful. (ni adverbial copula.)

It sounds like it's a lie.- Could imply something might be a lie, i.e. one is incredulous, without completely denying the possibility it could be true.

- {{kieta} you ni} mieru

消えたように見える

[It] looks {in a way as if {[it] disappeared}}. (~you ni auxiliary.)

It seems to have disappeared.- Could be a magic trick, in which something hasn't actually disappeared, but appears to have, like that one in which you pretend to pull apart your thumb.

There are two ways these verbs are typically used in the negative. First, when something can't be perceived at all.

- nanimo mienai. nanimo kikoenai.

何も見えない。何も聞こえない。

Can't see anything. Can't hear anything.

Second, it's used with shika しか to say something can't be perceived "as anything but." Observe:

- hoshi wa mienai

星は見えない

The stars aren't seen.

[I] can't see the stars. - hoshi shika mienai

星しか見えない

Everything but the stars aren't seen.

[I] can't see anything but the stars.

[I] can only see the stars. - hoshi ni mienai

星に見えない

[It] can't be seen as a star.

[It] doesn't look like a star. - hoshi ni shika mienai

星にしか見えない

[It] can't be seen as anything but a star.

[It] doesn't look like anything but a star.

[It] looks exactly like a star.

The copulative "tastes," "smells" and "feels" are more complicated.

The two senses, gustation and olfaction, along with audition (sense of hearing), all translate to the same pattern in Japanese: a sensory noun marked as subject of suru する. The whole pattern is stative.

- ame no aji ga suru

雨の味がする

[It] gives off the taste of rain.

[It] tastes of rain. - ame no nioi ga suru

雨の匂いがする

[It] gives off the smell of rain.

[It] smells of rain. - ame no oto ga suru

雨の音がする

[It] gives off the sound of rain.

?[It] sounds of rain. (this sounds weird in English.)

I can hear the sound of rain coming from it.

It makes the sound of rain.

I suppose suru する in the sentences above can be said to verbalize a "stimulus"(term used in Kemmer, 1993: 136-137, as cited in Taniguchi, 1997:275).

A fourth noun that's typically used in this stimulus sense is ki 気, "feeling," which is closer to "intuition" in the example below, which is, too, stative:

- ∅ {{ima nara dekiru} ki ga suru}

今ならできる気がする

[I] {feel like {[I] can do [it] now}}.

In translations, sometimes a Japanese adjective translates to a perceptual stative verb in English. For example:

- kono keeki wa oishii

このケーキは美味しい

This cake is delicious.

This cake tastes good.

The verb "to feel" has two meanings. One is copulative while the other is cognitive.

The copulative "to feel" appears strictly in phrases like "the water feels cold," meaning "the water is cold."

By contrast, "I feel awful" doesn't ALWAYS mean "I'm awful," nor does "I feel a great disturbance in the force" means "I'm a great disturbance in the force." Such instances of "to feel" aren't copulative, but cognitive instead.

In other words, the copulative is "stimulus-based," while the cognitive is "experiencer-based."(see example (7a), (7b) in Taniguchi, 1997:276).

The verb kanjiru 感じる means "to feel" in Japanese. It seems that the experiencer-based reading is transitive and uses the wo を particle, while the stimulus-based is intransitive and makes use of the double subject construction.

- sakka-san no sakuhin e no ai wo kanjimasu

作家さんの作品への愛を感じます

[I] feel the creator's love toward [their] work. - {kuruma no nai} watashi niwa {yama ga tooku kanjiru}

車のない私には山が遠く感じる

To me, [who] {doesn't have a car}, {the mountain feels distant}.

- tooku kanjiru predicates the nominative (ga) small subject yama: kanjiru is the copulative verb, tooi is the adjectival complement conjugated to adverb for syntactical agreement.

- {yama ga tooku kanjiru} predicates the dative (ni) topicalized (wa) large subject watashi ni.

- no の is a subject marker here.

Perception verbs can occur in episodic sentences when they're relevant only to a particular span of time or event.

- hai, hai, kikoete-ru yo

はい、はい、聞こえてるよ

Yes, yes, [I] am hearing [what you say]. (right now.)

Yes, yes, [I] can hear [what you're saying]. (right now.)- ~te-ru ~てる is a common contraction of ~te-iru.

- ~te-ru ~てる is a common contraction of ~te-iru.

- ame no nioi ga shite-iru

雨の匂いがしている

[Something] is smelling of rain. (right now.)

Cognitive

Verbs of cognition, of thought, are also stative, however, these are a bit more complicated, for several exceptional reasons.

Verbs that mean "I think this" or "I think that" typically use quoting particles such as to と and tte って, or make sure of the demonstrative adverbs kou, sou, aa, dou こう, そう, ああ, どう.

- watashi wa {neko-musume ga kawaii} to omou

私は猫娘が可愛いと思う

I think that {cat-girls are cute}. (imho.) - dou omou?

どう思う?

How do [you] think?

What do you think about this? - watashi wa sou omou

私はそう思う

I think so.

That's what I think about it.

All verbs that express what someone "thinks" are stative in English, including those that are just "I think" or "I feel" with extra steps: I like, I love, I hate, I consider, I assume, I presume, I deduce, and so on.

- {sono doubutsu wa inu dewanaku, neko de aru} to suisoku suru

その動物が犬ではなく、猫であると推測する

[I] conjecture that {that animal isn't a dog, [it] is a cat.}

However, not all cognition verbs that are stative in English are stative in Japanese. Some of them require ~te-iru:

- ore wa koukai-shite-imasu

俺は後悔しています

I regret [that]. - {koukai suru} hito

後悔する人

A person [who] {will regret [it]}.

A person [who] {regrets}. (habitually.)

Some of them may translate to "to feel" in English, making them even more complicated to understand:

- ochi-komu

落ち込む

To feel down. (in the future.)

- This is a compound verb.

- ochiru

落ちる

To fall. - komu

込む

To push into. - Because ~komu is eventive, ochi-komu is also eventive.

- ochi-konde-iru

落ち込んでいる

To be feeling down. (in the present.)

In some cases it's more complicated. For example, ai suru 愛する is stative, but it's typically used in ~te-iru form.

- kimi no koto wo aishite-masu

君のことを愛してます

[I] love you.- Note: the abbreviated ~te-ru becomes ~te-masu.

- {ai suru} hito

愛する人

A person [whom] {[one] loves}.

As we've seen previously, some English cognition verbs translate to Japanese as adjectives. These include:

- suki da

好きだ

Is liked. (Japanese adjective.)

To like. (English verb.) - kirai da

嫌いだ

Is disliked. Is hated.

To dislike. To hate.- Note: kirai does NOT contain an ~i ~い copula, it just ends in ~i ~い.

- Morphologically, suki and kirai are the ren'youkei (which ends in the ~i vowel) of the verbs suku 好く and kirau 嫌う, respectively.

- hoshii

欲しい

Is wanted.

To want. - iya da

嫌だ

Is unwanted.

To not want. Would rather not. - kowai

怖い

Is scary.

Fears.

The verb kangaeru 考える means "to consider," but typically translates to "to think." Considering something something else is stative.

- {{yameta} hou ga ii} to watashi wa kangaemasu

やめた方がいいと私は考えます

I consider {[it] being better were {[you] to stop [doing that]}}.

I think that {[it] would be better if {[you] stopped [doing that]}}.

Both kangaeru and omou can be used in ~te-iru to force an episodic reading.

- watashi wa {kore ga tadashii} to omotte-imasu

私はこれが正しいと思っています

I think that {this is right}. (right now, I'm feeling it is so.) - kre wa nanimo kangaete-inai

彼は何も考えていない

He is not thinking anything. (while doing a certain activity that we're talking about right now.)

The verb wakaru わかる, "to understand," translates to the SAME THING in English even in ~te-iru form. Nevertheless, the ~te-iru form is only used when it's episodically relevant.

- wakaru wa

わかるわ

[I] understand. (gnomic.)

I get it. I totally get it. I feel ya. - wakatte-masu!

わかってます!

[I] understand. (episodic.)

I get it, okay? You don't have to say it twice. - WAKATTE MASU TTE!!

わかってますって!!

I SAID I GET IT, DUDE, STAHP!!

The verb shiru 知る is exceptional, as it's hard to classify it as either stative or eventive. Its main problem is the asymmetry in how it's normally used:

- *shiru ka?

知るか?

- Only used like this to say "how would I know?!" when angry at someone.

- shitte-iru ka?

知っているか?

Do [you] know [it]? - shitte-iru

知っている

[I] know. - shiranai

知らない

[I] don't know. - *shitte-inai

知っていない

When asking someone whether they know something, ~te-iru is used. When answering, it's used only in the affirmative, not in the negative.

The affirmative requires ~te-iru, so it looks like an eventive verb, but the negative forbids ~te-iru, so it looks like a stative verb.

There are reasons to believe shiru 知る is eventive, however, and means "to come to learn" rather than "to know" something. Observe:

- shinda. shinde-iru

死んだ。死んでいる

Died. To be dead. - shitta. shitte-iru

知った。知っている

Came to learn. Has come to learn, i.e. knows. - omotta. omotte-iru

思った。思っている

Thought. Thinks.

Above we can see that shiru resembles the eventive verb shinu more than it resembles the stative verb omou.

If someone "died," as result they will be dead. If you "learned" something, as result you will know something. Both these verbs express that an event occurred in the past, and there's a state resultant of the event.

By contrast, if you "thought" something, we understand that you no longer "think" that way. When a stative verb is used, it implicates the state is true in the past, but not in the present anymore, which is different from how shiru works..

The verb oboeru 覚える is similar to shiru, but has a different meaning. It's about learning and memorizing things, and it's an eventive verb in spite of sometimes translating to the stative "remember" in English.

- {kanji wo oboeru} nowa muzukashii

漢字を覚えるのは難しい

{Learning kanji} is hard. (in the sense of studying and memorizing it.) - ore no koto oboete-iru ka?

俺のこと覚えているか?

Do [you] remember me? (in the sense of still having me in your memory currently.)

Relational

Some statives relate two entities in some abstract way. For example:

- kore wa sore towa chigau

これはそれとは違う

This differs with that.

This and that are different.- Note: machigau 間違う, "to make a mistake," is eventive, so if you make a mistake, you'll need the episodic machigatte-iru 間違っている instead.

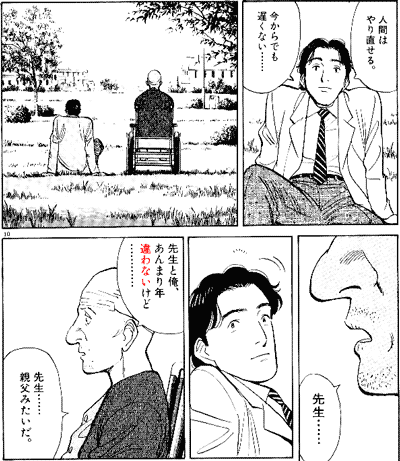

- Context: a doctor talks to a patient in wheelchair, who is also a criminal.

- ningen wa yari-naoseru.

人間はやり直せる。

Humans can do-over.

Humans can [start again].

- yari-naoseru - potential verb.

- yari-naosu

やり直す

To do over.

To do something again. - yaru

やる

To do.

- ima kara demo osokunai......

いまからでも遅くない・・・・・・

Even from now isn't late......- You can still start over, it isn't too late to begin now.

- sensei......

先生・・・・・・

Doctor...... - sensei to ore,

anmari toshi

chigawanai kedo............

先生と俺、あんまり年違わないけど・・・・・・・・・・・・

[You] and me, [our] ages don't differ much, but.........- We are about the same age, but...

- sensei...... oyaji mitai da.

先生・・・・・・親父みたいだ。

[You]...... are like [my] father.

Examples of relative verbs:

- fukumu

含む

To include. - zokusuru

属する

To associate with. - bunrui sareru

分類される

To be categorized as.

In some cases, a verb has a stative sense and an eventive sense.

The verb hairu 入る, "to enter," normally would be eventive, as it denotes a pretty obvious movement action, however, it's treated as stative when it means "to enters a category," a group, "to be counted as."

- banana wa hako ni haitte-imasu ka?

バナナは箱に入っていますか?

Is the banana entered inside the box?

Is the banana inside the box?- Eventive.

- banana wa o-yatsu ni hairimasu ka?

バナナはおやつに入りますか?

Do bananas enter snacks?

Do bananas count as snacks?- Stative.

- Note: typically used as a joke in reference to school policies that restricted the amount of money students could spend on snacks in school trips, e.g. to up to 300 yen. If bananas didn't count as snacks, then maybe neither did oranges, or watermelons, and maybe fanta isn't a snack either, who knows.[バナナはおやつに入りますか?とはどういう意味なんでしょうか? - chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp, accessed 2020-07-18]

The verb sugiru すぎる which means "to exceed" is eventive. However, ~sugiru ~すぎる, "exceedingly," as an suffix on adjectives, is stative, based on fact that adjectives are inherently stative.

- yakusoku no jikan wo sugite-iru

約束の時間を過ぎている

[It] has exceeded the promised time.

You're late. The time we agreed on has already passed. - kawai-sugiru!

可愛すぎる!

[It] is exceedingly cute!

[It] is too cute!

The comparisonal niru 似る, "to resemble," is eventive in Japanese, despite being stative in English.

- haha to yoku nite-iru

母とよく似ている

[He] resembles [his] mother a lot.

References

- 金田一春彦, 1950. 國語動詞の一分頬. 言語研究, 1950(15), pp.48-63.

- Vendler, Z., 1957. Verbs and times. The philosophical review, 66(2), pp.143-160.

- Carlson, G.N., 1977. Reference to kinds in English.

- Krifka, M., Pelletier, F.J., Carlson, G., Ter Meulen, A., Chierchia, G. and Link, G., 1995. Genericity: an introduction.

- Taniguchi, K., 1997. On the semantics and development of copulative perception verbs in English: A cognitive perspective. English Linguistics, 14, pp.270-299.

- Fernald, T.B., 1999. Evidential coercion: Using individual-level predicates in stage-level environments.

- Sugita, M., 2009. Japanese-TE IRU and-TE ARU: The aspectual implications of the stage-level and individual-level distinction. City University of New York.

- Bertinetto, P.M. and Lenci, A., 2010. Iterativity vs. habituality (and gnomic imperfectivity). Quaderni del laboratorio di linguistica, 9(1), pp.1-46.

- 加藤重広, 2010. 北奥方言のモダリティ辞. 北海道大学文学研究科紀要, 130, pp.125-左.

- 鈴木彩香, 2014. ガ格の総記/中立叙述用法と裸名詞句の総称/存在解釈の統一的説明. 言語学論叢 オンライン版, (7).

- Freund, N., 2016. Recent Change in the Use of Stative Verbs in the Progressive Form in British English: I’m loving it. University of Reading Language Studies Working Papers, 7, pp.50-61.

Wow. this is so detailed. I don't understand all of it after the first read-through but it's already helped me to make some connections I wouldn't have made otherwise. Not at all what I expected from a website called Japanese with Anime!

ReplyDelete