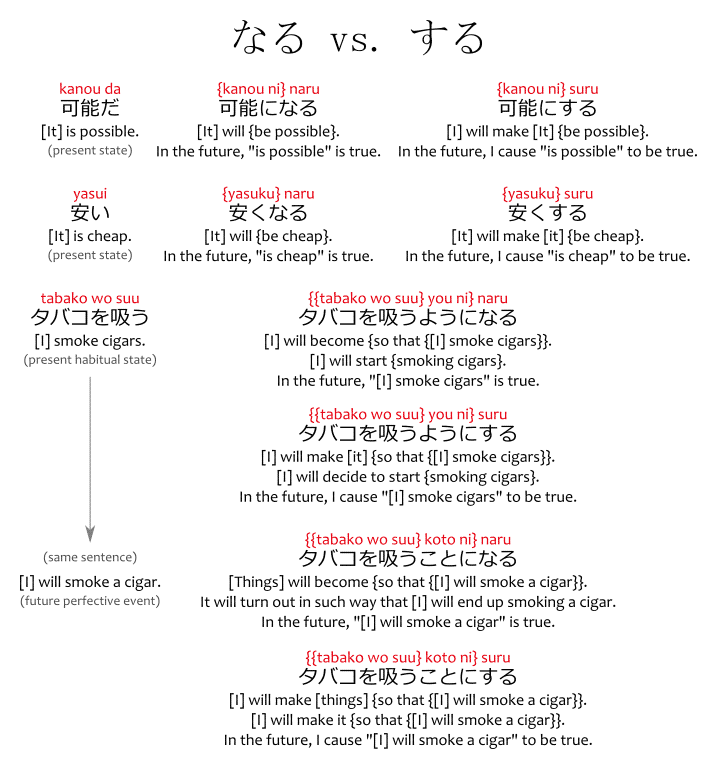

In Japanese, the verbs naru なる and suru する form an ergative verb pair of eventivizers: they're eventive verbs used with the adverbial form of statives, such as adjectives, stative verbs, and habitual predicates, in order to make said stative to behave like an eventive.

Notably, Japanese statives in nonpast form lack a future tense, so either a futurate or an eventivizer will be necessary to express a state is true in the future.

- musuko ga isha da

息子が医者だ

[My] son is a doctor. (present tense.)

*[My] son will be a doctor. (can't mean the future tense.) - musuko ga isha ni naru

息子が医者になる

[My] son will be a doctor. - watashi ga musuko wo isha ni suru

私が息子を医者にする

I will make [my] son be a doctor.

Note: naru and suru have other functions, but this article won't focus on them.

Grammar

In Japanese, statives don't have a future tense in nonpast form, only eventive verbs do. In order to use a stative in the future tense, it's necessary to first convert it to an eventive verb through an eventivizer.

There are two eventivizers: naru and suru. Both of them take the stative as an adverb. Syntactically, they differ in transitivity: naru is intransitive, while suru is transitive. Semantically, suru causes naru to happen.

- SubjectがAdverbial Stateなる

Subject will be state in the future. - SubjectがCauseeをAdverbial Stateする

Subject causes causee to be state in the future.

Naturally, naru is simpler, so let's start with it.

Will Be vs. Will Become

Although naru is typically translated as "will become," it actually means "will be." The difference between these two phrases is that "will become" entails a change occurs, while "will be" implicates a change occurs. Observe:

- kyou wa samui.

今日は寒い。

Today is cold. - ashita mo {samuku} naru.

明日も寒くなる。

Tomorrow, too, will {be cold}. (right.)

#Tomorrow, too, will become {cold}. (wrong.)

If we say "it will become cold," that entails it isn't cold right now, and it will CHANGE to cold in the future. Consequently, we can't use "become" in cases where it's cold right now and will be cold in the future, too, because then there is no change happening.

However, we can use naru なる in those situations, so naru is closer to "will be" than "will become"[be とbecome の違いって何ですか?? - detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp, accessed 2019-01-24].

Syntax

Eventivizers turn an state into an event. Syntactically, the eventivizer is a verb, so it must be modified by an adverb. How we turn the state into an adverb depends on what sort of word the state is.

When we have an i-adjective, its adverbial form is ~ku, so we end up with ~ku naru ~くなる.

- hayai

速い

To be fast. To be quick. - {hayaku} hashiru

速く走る

To run {quickly}. - {hayaku} naru

速くなる

Will {be quick}. To become {quick}.

When we have a na-adjective the da だ predicative copula is replaced by the ni に adverbial copula, so we end up with ~ni naru ~になる.

- jiyuu da

自由だ

To be free. - {jiyuu ni} ugoku

自由に動く

To move {freely}. - {jiyuu ni} naru

自由になる

Will {be free}. To become {free}.

The same syntax applies to nouns, a.k.a. no-adjectives.

- Context: the protagonist confesses to his mother his aspirations.

- boku, mangaka ni naru

僕 マンガ家になる

I'll become a manga artist. - dame

駄目lol no u wont

No. - suggee sokutou

すっげー即答

[That was] an extremely fast answer.- She didn't even think twice.

Such adverbs can be marked by the wa は particle when they're topics, and can also be marked by the mo も particle.

- {kirei ni} wa naranai ga, {kawaiku} wa naru

綺麗にはならないが、可愛くはなる

{Pretty} [it] won't become, but {cute} [it] will.

[It] won't become {pretty}, but [it] will become {cute}.- An example of contrastive wa は.

- {{isu ni} mo {beddo ni} mo} naru

椅子にもベッドにもなる

[It] becomes {{a chair} and {a bed}}.- In the sense you can use it either as a chair or as a bed.

- Note that this is a habitual predicate with a potential entailment: "it becomes a chair" means "it can become a chair." Also note that since naru なる is eventive, it can express habituals such as this.

When we have a state expressed by a verb, i.e. a verbal state, the verb itself won't have an adverbial form. The adverbial form of adjectives is a ren'youkei 連用形, but the ren'youkei of verbs isn't adverbial, so something else is necessary.

- ugoki

動き

Movement.- The ren'youkei of a verb is more of a noun form rather than adverbial form.

This something would be the you da ようだ suffix, which is conjugated like a na-adjective, so its adverbial form is ~you ni ~ように, and we'll end up with ~you ni naru ~ようになる.

- {{ugoku} you ni} naru

動くようになる

To become {in a way [that] {moves}}.

To start {moving}.

It's worth noting that you よう has other uses, some of them very similar to the above. We'll see some of such functions through this article.

The negative form of a verb ends in ~nai ~ない, and this ~nai is conjugated as an i-adjective. Consequently, there are two ways for a verb in negative form to become an adverb depending on whether it's treated as a verb or treated as an i-adjective.

- {{ugokanai} you ni} naru

動かないようになる

To become {in a way [that] {doesn't move}}.

To stop {moving}. - {ugokanaku} naru

動かなくなる

Although there doesn't seem to be any difference in the above with the naru eventivizer, there's a difference when used with the suru eventivizer, we'll see in detail later in this article.

するようになる vs. できるようになる

The phrase ~you ni naru is used to eventivize a state expressed by a verb. There are two types of such states: states expressed by stative verbs, and eventive verbs that express habitual predicates, which also count as states.

Observe:

- sakana wa oyogu

魚は泳ぐ

Fish swim. (habitual state.)

Fish will swim. (future perfective event.) - sakana wa oyogeru

魚は泳げる

Fish can swim. (potential state.)

Above we have the eventive verb oyogu, and the potential verb oyogeru, which is stative. We can use ~you ni naru with both.

- sakana wa {{oyogu} you ni} naru

魚は泳ぐようになる

The fish will become {in a way [that] {swims}}.

In the future, "fish swim" will be true. - sakana wa {{oyogeru} you ni} naru

魚は泳げるようになる

The fish will become {in a way [that] {can swim}}.

In the future, "fish can swim" will be true.

One question people tend to have is what's the difference in sentences such as the above.

When we say "fish swim," we're also saying that "fish can swim," because if they couldn't swim, they wouldn't swim. If John swims, that means he knows how to swim. The habitual meaning entails the potential meaning, which is where the confusion comes from.

Fortunately, it's very easy to solve this confusion.

The phrase "will become" implicates that something isn't true right now, but will be true in the future. In other words, it will go from negative to positive. So all we have to do is check what's the negative to understand what we're really implicating.

- sakana wa oyoganai

魚は泳がない

Fish don't swim. - sakana wa oyogenai

魚は泳げない

Fish can't swim.

The phrases above look very similar, but there's a fundamental difference between them.

- The fish that "can't swim" don't swim because they can't.

- The fish that "don't swim" may be able to swim if they wanted to, but maybe they don't like swimming, so they don't.

In other words, a phrase like oyogeru you ni naru expresses that, currently, the subject can't do the thing even if they wanted to, while oyogu you ni naru expresses that the subject could do the thing, but they don't do it, and they will start doing it in the future.

As a consequence, oyogeru you ni naru typically implies that someone struggled a lot to finally become able to do swim, while oyogu you ni naru can be a mere change of habits.

Potentials are typically used in double subject constructions. They use the ga が particle instead of the wo を particle, even if the verb they derive from is transitive. Observe:

- watashi wa hon wo yomu

私は本を読む

I read books. - watashi wa {hon ga yomeru}

私は本が読める

{Books are readable} is true about me.

I {can read books}.

The same is true when they're eventivized.

- watashi wa {{hon wo yomu} you ni} naru

本を読むようになる

I'll become {in a way [that] {reads books}}.

I'll start {reading books}.- Meaning that I can read books right now, but I don't, because I don't want to. I simply don't have that habit yet.

- watashi wa {{hon ga yomeru} you ni} naru

私は本が読めるようになる

I'll become {in a way [that] {can read books}}.

I'll become {able to read books}.- Meaning that I can't read books right now, perhaps due to poor sight, but in the future I'll be able to, perhaps due to buying a neat pair of reading glasses.

Conjugation

Once a state has been eventivized, the eventivizer can be conjugated. Observe:

- samui

寒い

[It] is cold. (present state.) - {samuku} naru

寒くなる

[It] will {be cold}. (future event.)- Implicature: it's not cold right now, only in the future it's cold.

- samukatta

寒かった

[It] was cold. (past state.)- Implicature: it's not cold right now, only in the past it's cold.

- {samuku} natta

寒くなった

[It] became {cold}. (past event.)

- Implicature: it's cold right now, and in the past it wasn't cold.

This conjugation is particularly useful with habitual predicates. For example:

- Context: someone never goes to school, then one day they start.

- {{gakkou wo kayou} you ni} natta

学校を通うようになった

[They] became {in a way [that] {goes to school}}.

[They] started {going to school}. - Context: someone became a wizard.

- {{mahou ga tsukaeru} you ni} natta

魔法が使えるようになった

[They] became {in a way [that] {can use magic}}.

[They] became {able to use magic}.

Other conjugations are also possible, for example:

- {ookiku} nattara {nani ni} naritai?

大きくなったら何になりたい?

[You] want {to be what} when [you] become {big}?

What do you want to be when you grow up?

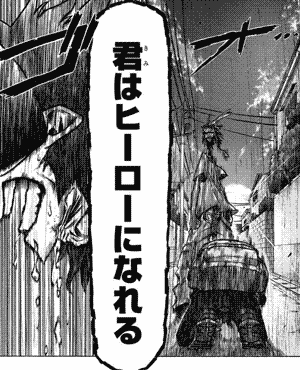

- kimi wa hiiroo ni nareru

君はヒーローになれる

You can become a hero.- nareru - potential verb derived from naru.

- Context: it's Christmas and a grade school student is cleaning the school windows. But why?

- watashi kyonen wa ii ko

janakatta

mitai de Santa-san

kite-kurenakatta-n-desu

私去年は良い子じゃなかったみたいでサンタさん来てくれなかったんです

It seems last year I wasn't a good child so Santa-san didn't come [for me]. - dakara kotoshi wa

ii ko ni narou to

omotte!

だから今年は良い子になろうと思って!

So [I] thought: this year [I] will become a good child!- narou - the volitional form of naru.

By the way, in the anime fandom, "Narou" sometimes refers to shousetsu-ka ni narou 小説家になろう, "let's become a novelist," a website (syosetu.com, URL is nihon-shiki romaji for shousetsu) that hosts web-novels, many of which have been adapted to anime, e.g. Re:Zero (ncode.syosetu.com/n2267be/).

Causative Eventivizers

The eventivizer suru is the causative variant of the eventivizer naru. Observe:

- heya ga akarui

部屋が明るい

The room is bright.

The room is well-lit. - heya ga {akaruku} naru

部屋が明るくなる

The room will {be well-lit}.

The room will become {well-lit}. - Tarou ga heya wo {akaruku} suru

太郎が部屋を明るくする

Tarou will make the room {be well-lit}.

Tarou will make the room {well-lit}.

Tarou will make the room become {well-lit}.

As you can see above, the subject of a naru-sentence becomes the object of a suru-sentence. This happens because the subject of a suru-sentence is the causer (Tarou), and the object is the causee (heya).

In a naru-sentence, the state will apply to the subject.

In a suru-sentence, the causer will cause the state to apply to the causee.

- nedan wo yasuku shita

値段を安くした

[Someone or something] made the price become cheap. - nedan ga yasuku natta

値段が安くなった

The price became cheap.

This is essentially the difference between the two: a sentence with suru always have an external causer making the state-change occur.

There are several common situations where it's used that are difficult to understand unless you understand this. For example, might have heard this sentence before:

- terebi wo miru toki wa heya wo {akaruku} shite, hanarete mite-kudasai

テレビを見る時は部屋を明るくして離れて見て下さい

When watching TV, please make the room {well-lit}, distantiate and watch.- A common warning found in TV anime, telling children to watch TV from afar in a well-lit room, rather than from up close in a dark room.

In the sentence above, shite して is the te-form of suru, and the warning tells the audience to change the state of the room to "well-lit," akarui.

Another example:

- heya wo {kirei ni} shita

部屋を綺麗にした

I cleaned up the room. (typical translation.)

I made the room {pretty}. (literally.)

Above, we have the adjective "pretty," kirei 綺麗, but for some reason making the room "pretty" translates to cleaning up the room. This is just how the word is used in Japanese.

Another common usage of suru would be this:

- shizuka ni shinasai

静かにしなさい

Be quiet! (common translation.)

Silence!- shinasai - nasai なさい form of suru.

- shizuka da

静かだ

Is quiet.

Above, the typical translation would be "be quiet," however, the literal meaning is "make yourself quiet" or "make the classroom quiet."

Another common, hard to figure out example:

- ii kagen ni shi-yagare,

いい加減にしやがれ、

[That's enough],

[Stop that],

[Cut it off], - kono yarou!!!

この野郎!!!

[You bastard]!!!

Above, we have the meireikei 命令形, "imperative form," of ~yagaru ~やがる, which typically translates to "to dare to," in the sense of doing something that the speaker doesn't like, however its meaning is more general, and can be used in any situation in which the speaker is expressing his hate for the target.

If we reduce it, we get ii-kagen ni shiro いい加減にしろ, which is an imperative of ii-kagen ni suru いい加減にする, which would be the causative of ii kagen da いい加減だ.

The phrase ii kagen いい加減 means literally a "good degree," and it's often used like this to tell people to keep it at "a good degree," in other words, what they're doing is too much and should stop, go back, sit down, shut up, or so on.

Requests with ~ni suru can also be used to apply a state to the speaker themselves. For example:

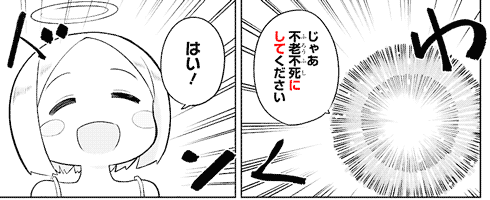

- Context: an angel is granting any desires to a soul about to be reincarnated.

- jaa furou-fushi ni shite-kudasai

じゃあ不老不死にしてください

Then, please make [me] immortal.- furou-fushi

不老不死

Non-aging, non-dying. (yojijukugo 四字熟語)

Perpetually young and immortal.

- furou-fushi

- waku

わく

*excited* (psychomime) - hai!

はい!

Okay! - don

ドン

*bam*

Above, furou-fushi is a state applied the speaker wants applied to themselves. Afterwards, they'd be able to say: watashi wa furou-fushi da 私は不老不死だ, "I'm immortal."

In some cases, ~ni suru is used to refer to the way someone is treated. Compare:

- yome ni suru

嫁にする

To make [someone] [one's] bride.

To make [someone] [one's] wife.

To marry [someone].- Here, we make someone a yome 嫁.

- baka ni suru

バカにする

To make [someone] an idiot.

To take [someone] for an idiot.

To mock [someone].- Here, we make someone a baka バカ.

The latter is typically used in a negative request, as baka ni shinaide バカにしないで or baka ni suru na バカにするな.

- Context: Kaguya is asked a quiz question that's too easy for a genius like her, and gets congratulated after getting it right.

- baka ni shinaide kudasai...

馬鹿にしないでください・・・・・・

[Don't take me for an idiot.] - konna kodomo-muke no mondai

tokete touzen desu...

こんな子供向けの問題

解けて当然です・・・

A question [made] for kids like this,

[for me] to solve [it] is [only] natural...

This same function also applies to things. Treating something as something else often means using it like if it were something else. For example:

- Context: the princess is dead. The demon cleric tells the demon lord how she died.

- chiiin

ちーーーん

*ring of a bell* (sound effect used when a character dies or is defeated, probably originates from the bell used in a butsudan 仏壇, a "Buddhist altar" for a deceased family member.) - doku kinoko no boushi wo futon ni shita sou desu...

毒キノコの帽子を布団にしたそうです・・・

It seems that [she] made a poisonous mushroom's cap into a bed.- In other words, she used the cap (top part) of the mushroom as if it were a bed.

- She treated it as a bed.

- futon

布団

Traditional Japanese bedding, typically placed on a tatami floor. The term refers to both the mattress and the duvet, but just "bed" is a good enough translation most of the time..

- moshikashite baka na no ka?

もしかしてバカなのか?

Could it be that [she] is an idiot?

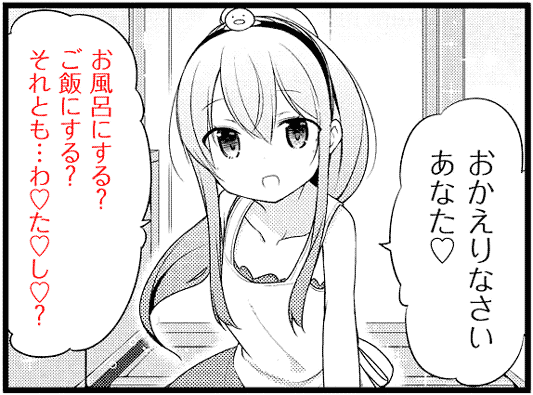

Another usage is to select one item among choices. For example:

- Context: Yukimoto Yuzu 雪本柚子 imagines herself as a bride who would support her future husband.

- okaerinasai anata ♡

おかえりなさいあなた♡

[Welcome home, dear.]- anata

あなた

You. (second person pronoun.)

Sometimes used by a wife to refer to her husband.

- anata

- ofuro ni suru?

gohan ni suru?

soretomo... wa... ta... shi...?

お風呂にする?

ご飯にする?

それとも・・・わ♡た♡し♡??

[What do you want to do]?

[Eat]? [Take a] bath? Or... me? - This is a trope called shinkon santaku 新婚三択, "newly-wed three choices." There are variations, but they all use the pattern ~ni suru because it's about choosing one of the three choices.

As one would expect, if ~ni suru causes something in the future, then da だ states it in the present.

- docchi ni suru?

どっちにする?

Which will [you] make [it]?

Which will [you] choose? - docchi da?

どっちだ?

Which [one] is [it]?

Exceptionally, da だ can be used metalinguistically, like quotations, in which case it ignores usual syntax rules. Similarly, ni suru can be used metalinguistically. For example, they can be used directly after an i-adjective if we assume we're referring to the word literally.

- "tsumetai" da

"冷たい"だ

[It] is "cold."

[I choose "cold"] - "tsumetai" ni suru?

"冷たい"にする?

Will [you] make [it] "cold"?

[Will you choose "cold"]?

Concrete Causatives

With verbal states, you ni suru ようにする is only used when it makes sense to say that someone "did something" to make the state true. For example:

- {{itsudemo nigerareru} you ni} shita

いつでも逃げられるようにした

[I] did something {so that {[I] can escape anytime}}.

In the sentence above, we understand that someone made some preparations so that if they're ambushed and need to escape, they "can escape" without trouble.

Since "did something" is extremely vague, there are cases where it doesn't make sense to use suru する, and a more concrete eventivizer is used after ~you ni ~ように. For example:

- {{nanimo mienai} you ni} shita

なにも見えないようにした

[I] did something {so that {[I] can't see anything}}.

[I] did something {so that {[he] can't see anything}}.

- Although this sentence makes sense, we have no idea what I did. We only know the end result.

- {{nanimo mienai} you ni} me wo tojita

何も見えないように目を閉じた

[I] closed [my] eyes {so that {[I] can't see anything}}.- Here, the end result is the same, we've merely given a more concrete description of what caused the outcome.

Essentially, this means that suru する is the most basic, abstract causative eventivizer, and the same grammatical syntax can be used with any eventive predicate by placing them after ~you ni.

Since ~you ni is simply the adverbial form for verbal states, the same should work with the adverbial form of adjectival states. And it does. To some extent. But it doesn't work exactly like ~you ni.

For example, you can say this:

- ishi ga tooi

石が遠い

The stone is far. - ishi wo tooku shita

石を遠くした

[I] made the stone far.- Although this sentence makes no sense most of the time, it's not grammatically wrong. It could be used, for example, if someone was painting a picture that had a stone in it, and they didn't like the picture with the stone too close, so they redrew it to make the stone far.

- ishi wo tooku nageta

石を遠く投げた

[I] threw the stone far.

In fact, there are various cases where suru する wouldn't be used because it's too vague, but the sentence has an adverb that represents the final state nonetheless. For example:

- ishi wo takaku mochi-ageta

石を高く持ち上げた

[I] held the stone up high.

Modifying the causative with a deadjectival adverb only works when the action directly causes the state. Holding up something causes it be high, throwing something causes it to be far.

When the action indirectly causes the state, we assume there's some intermediary event between the causative and the final state, so we need to eventivize the state first with naru.

Syntactically, the causer must be the subject of the matrix clause, but in a sentence like "X is state," X is the subject of the clause.

When you have a sentence in which "I do something to X that makes X become state," then X can be just the object instead of subject, but if the sentence is "I do something to Y that makes X become state," then X must be the subject of its own subordinate clause.

In the latter case, simply conjugating an adjective to adverbial form isn't enough to create a clause scope and you'll need ~you ni ように, which results in the sentence naru you ni なるように. Observe:

- shitsu-on wa ni-juu-do da

室温は28度だ

The room temperature is 28 degrees [Celsius]. - {{shitsu-on ga {ni-juu-do ni} naru} you ni} eakon wo chousetsu shita

室温が28度になるようにエアコンを調節した

{So that {the room-temperature would be {28 degrees}}}, [I] adjusted the air conditioner.- This sentence makes sense because me adjusting the air conditioner doesn't directly change the room temperature.

- First, I change the air conditioner.

- Then, the air conditioner changes the temperature.

- There are two events, so there's an intermediary event between what I did and the final state I'm aiming for, which is why ni naru is used.

- *{shitsu-on ga ni-juu-do ni} eakon wo chousetsu shita

#shitsu-on ga {ni-juu-do ni} eakon wo chousetsu shita室温が28度にエアコンを調節した

- This sentence is grammatically wrong for syntactical reasons.

- First, eakon wo chousetsu shita requires a subject. The correct sentence has the covert topic "I," watashi wa 私は, as the subject of the matrix clause: "I adjusted the air conditioner."

- This means that the subject shitsu-on ga must be in the subordinate clause. However, deadjectival adverbs such as ni-juu-do ni don't create a clause scope, so this would be syntactically wrong.

- On the other hand, if shitsu-on ga was in the matrix clause, that would translate to "the room temperature adjusted the air conditioner to 28 degrees," which makes no sense at all.

Another example:

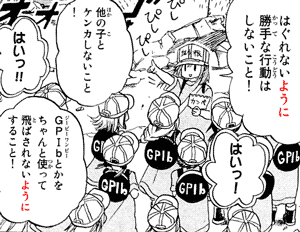

- Context: "platelets," kesshouban 血小板, drawn as cute anime girls, receive their marching orders.

- {{hagurenai} you ni} {katte na} koudou wa shinai koto!

はぐれないように勝手な行動はしないこと!

Do not [act on your own] {so that {[you] don't stray away}}!- katte

勝手

(refers to doing things without consulting others.) - hagureru

逸れる

To stray away [from a group]. To lose sight of [one's group]. - Therefore, hagurenai you ni suru means to do something in order to "not stray away."

- katte

- hai'!

はいっ!

Yes, [ma'am]! - hoka no ko to kenka shinai koto!

他の子とケンカしないこと!

Do not fight with other kids! - hai'!

はいっ!!

Yes, [ma'am]! - jiipiiwanbii toka wo chanto tsukatte {{tobasarenai} you ni} suru koto!

GPIbとかをちゃんと使って飛ばされないようにすること!

Do use GPIb, etc. properly {so that {[you don't get sent flying away]}!- GPIb, Glycoprotein Ib, allow platelets to adhere at sites of injury.

- tobu

飛ぶ

To jump. To fly. - tobasu

飛ばす

To make [something] fly. (ergative verb pair.) - tabasareru

飛ばされる

To be made fly [by something]. (passive form.)

~なくなる vs. ~ないようになる

When a state expressed by a verb in the negative form becomes eventivized, there are two possible patterns in syntax: ~naru naru ~なくなる and ~nai you ni naru ~ないようになる.

For the causative: ~naku suru ~なくする and ~nai you ni suru ~ないようにする.

The differences between them are as follows(池上, 2002:1):

- ~naku naru and ~nai you ni naru are practically synonymous, but it's easier to turn simple predicates, with few constituents, into ~naku naru, while more complicate ones tend to use ~nai you ni naru.

- ~naku suru and ~nai you ni suru differ in meaning: ~naku suru is used when the subject directly causes the state to become negative, when done indirectly ~nai you ni suru is used.

In summary, it doesn't matter with naru, but it matters with suru.

A couple of examples(池上, 2002:11):

- watashi wa {{musuko ga heya kara denai} you ni} shita

私は息子が部屋から出ないようにした

I made [it] {so that {[my] son doesn't leave the room}}.

I made [it] {so that {[my] son can't leave the room}}. (potential entailment.)- For example: by locking the door, which would indirectly result in him not leaving the room.

- ?watashi wa musuko wo {heya kara denaku} shita

私は息子を部屋から出なくした

- Since whether the son leaves the room or not depends on the son's volition, and you can't directly alter their volition, this doesn't make sense.

- watashi wa te-ashi wo shibatte kare wo {ugokenaku} shita

私は手足を縛って彼を動けなくした

I tied [his] arms-and-legs, making him {unable to move}. - watashi wa te-ashi wo shibatte {{kare ga ugokenai} you ni} shita

私は手足を縛って彼が動けないようにした

I tied [his] arms-and-legs, making [it] {so that {he can't move}}.

Observe in the examples above that when ~naku is used, the causee is marked by the wo を particle, but when ~nai you ni is used, the causee is marked by the ga が particle.

This means that, syntactically, when ~naku is used, the causer does something to the causee directly that applies the state, while when ~nai you ni is used, the causer doing something to something else that causes the whole predicate to become true.

- watashi wa kare wo ugokenaku shita

watashi causes ugokenaku to apply to kare.

Which means watashi directly alters kare. - watashi wa kare ga ugokenai you ni shita

watashi causes kare ga ugokenai to be true.

Which means watashi causes the situation to happen.

Stativized Eventivizers

Since eventivizers can be conjugated like any other verb, they can also be stativized through the stativizers ~te-iru ~ている and ~te-aru ~てある.

Like other ergative verb pairs, when conjugated to ~te-iru ~ている form, typically the unaccusative naru has the resultative meaning, while the causative suru has the progressive meaning.

~なっている

The resultative natte-iru なっている is used when something is in a state resultant of a past change. In this regard, there are two distinct uses.

First, when the change was observable in the past, in which case it's possible to replace natte-iru by the past form natta なった, or use an adverb such as mou もう, "already." For example(佐藤, 1999:3):

- garasu ga konagona ni natte-iru

ガラスが粉々になっている

The glass has become in pieces. (present perfect translation.)

The glass is in pieces. (resultative state translation.) - garasu ga konagona ni natta

ガラスが粉々になった

The glass became in pieces. (past change.) - garasu ga mou konagona ni natte-iru

ガラスがもう粉々になっている

The glass has already become in pieces.

The glass is already in pieces.

Second, when the change wasn't observable, in which case we can't replace natte-iru with natta. For example(佐藤, 1999:3):

- kaigan no aru bubun wa irie ni natte-iru

海岸のある部分は入江になっている

The part that has a seashore has become an inlet.- An irie 入り江, "inlet," in a sea or river is an indentation caused by erosion, so it ends up in a shape that looks like the body of water is "entering" the land.

- *kaigan no aru bubun wa irie ni natta

海岸のある部分は入江になった

- Unless we're telling a story about a time in which a place became an inlet, we can't use the past tense.

- *kaigan no aru bubun wa mou irie ni natte-iru

海岸のある部分はもう入江になっている

- Unless we have a place that isn't an inlet, and we have a reason to believe it will become an inlet in the future, we can't say it "already has become an inlet."

As you may imagine, the first natte-iru is very simple to understand. If something "became," natta, something else, it's natte-iru, "has become."

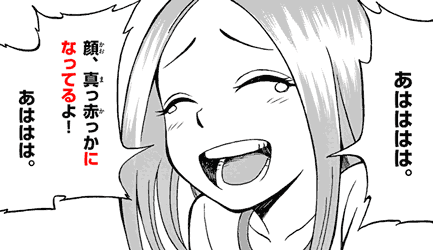

- Context: Takagi 高木 sees the outcome of her teasing.

- a-ha-ha-ha-ha.

あはははは。

*laughs.* - kao, {makka-kka ni}

natteru yo!

顔、真っ赤っかになってるよ!

[Your] face, [it]'s turned {really red}! - a-ha-ha-ha.

あははは。

*more laughs.*

The second natte-iru is bit more complicated, as it's only used when we assume that something caused the current state, either accidentally or deliberately, even if we don't know exactly what or who caused it.

In the case of the inlet, the inlet became an inlet due to erosion or something like that. We don't know for sure. But something made the inlet and inlet. Because, by default, we don't expect an inlet to exist, so something must cause it.

Similarly, several sentences with natte-iru assume a natural phenomenon caused the state per chance, or a person artificially made it happen deliberately. For example(佐藤, 1999:8–9):

- kono keitai-you no kamera wa totemo karuku natte-iru

この携帯用のカメラはとても軽くなっている

This portable camera is very light.- Implicature: the company made it so. They deliberately designed this product to be light-weight.

- {{takai ki no ha wo taberareru} you ni}

kirin no kubi wa nagaku natte-iru

高い木の葉を食べられるように

キリンの首は長くなっている

{So that {[it] can eat the leaves of tall trees}},

the neck of the giraffe is long.- Implicature: evolution made it so. Shorter-necked giraffes starved to death while longer-necked giraffes reigned supreme.

By contrast, this sort of natte-iru can't be used when we don't assume a cause for the current state. For example(佐藤, 1999:8–9):

- ??Tarou no taijuu wa totemo karuku natte-iru

太郎の体重はとても軽くなっている

Tarou's weight has become very light. (first type.)

??Tarou's weight is very light. (second type.)

- If an observable event, like magic, changed Tarou's weight to light, we can use natte-iru.

- However, if we're only observing that Tarou's "is very light-weight," we can simply say he's totemo karui とても軽い. There's no reason to use natte-iru.

- Unless, of course, there was an assumption that Tarou's weight was caused by something.

- For example, if we're playing a video-game in which characters are given random weights, then Tarou being light-weight is assumed to be caused by the same randomness that affects all characters, and we'd be able to use natte-iru.

This second type of natte-iru is typically used in sentences in which the state of something serves a purpose. In order to achieve that purpose, something was deliberately created in a way. In such cases, natte-iru is more natural than using the stative by itself. For example(佐藤, 1999:10):

- {{senshu ga gekitotsu shitemo kega shinai} you ni}

選手が激突しても怪我をしないように

{So that {even if a player crashed into [it] [they] wouldn't get hurt}}... - sakkaa no gooru posuto wa maruku natte-iru

サッカーのゴールポストは丸くなっている

...the soccer goalpost is round. - ?sakkaa no gooru posuto wa marui

サッカーのゴールポストは丸い

...the soccer goalpost is round.

- Although marui and maruku natte-iru both translate to "is round," the natte-iru sentence is preferred, because the clause presupposes a reason for the goalpost to be round.

- Someone made it round so that players wouldn't get hurt.

Sentences like the above are typically used when describing the function of devices, or that some rule or policy has been set as solution for some issue.

- jidou doa {{ga akanai} you ni} natte-iru

自動ドアが開かないようになっている

The automatic door is {in a way [that] {doesn't open}}.- e.g. someone set up the automatic door so that it doesn't open if it's too late in the night, or if there's too many people inside the store, or something like that.

The phrase natte-iru is sometimes used to say that something fulfills a purpose. In such cases, it won't always make sense to translate it to English as "is." For example(佐藤, 1999:10):

- korera no teiboku ga michibata no ikegaki ni natte-iru

これらの低木が道ばたの生垣になっている

These shrubs are serving as a roadside hedge.

These shrubs make a roadside hedge.

Another usage of natte-iru is when the structure of something fits the definition, such as the inlet we've seen previously. For example(佐藤, 1999:12, excerpt from 楡家の人々 1350):

- kaidan no shita wa, san-jou hodo no kobeya ni natte-iru

階段の下は三畳ほどの小部屋になっている

[The space] under the stairs has become a small room the size of three tatami mats.- ~jou

~畳

Counter for tatami mats, specially used to tell the area of a room.

- ~jou

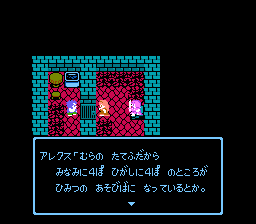

- Context: Alex talks about what he heard from the children.

- Arekusu: {mura no tatefuda kara

minami ni yon-po higashi ni yon-po no} tokoro ga

{himitsu no asobi-ba ni} natteiru toka.

アレクス「むらの たてふだから

みなみに4ぽ ひがしに4ぽ のところが

ひみつの あそびばに なっているとか。

Alex: the place

{four steps to south four steps to east from the village's sign}

has become {a secret playground} or something like that.

~している

The phrase shitte-iru しっている has its own set of complications.

To begin with, if shita した means someone caused a state in the past, and suru する means they'll cause it in the future, then shite-iru している means they're causing it in the present.

This is a bit different from natte-iru. Observe:

- heya ga kirei ni natte-iru

部屋が綺麗になっている

The room has become clean.- Someone cleaned it up in the past.

- heya wo kirei ni shite-iru

部屋を綺麗にしている

[Someone] is making the room become clean.- Someone is cleaning it up in the present.

With natte-iru, the cause of the change has finished in the past, while with shite-iru the cause of the change persists in the present.

Also, shite-iru can have another meaning of the ~te-iru form, which is iterative. For example:

- {heya wo kirei ni shite-iru} hito

部屋を綺麗にしている人

Someone [who] {is making the room clean}. (progressive.)

Someone [who] {has been making the room clean}. (iterative.)

In the progressive sense, we understand that, right now, they're cleaning up the room.

In the iterative sense, we understand that they're the sort of person that has been cleaning up the room, presumably their own bedroom, multiple times in the past and will continue to do so in the future, even if they aren't doing it at this exact moment.

When shite-iru is used with habituals, it means someone is deliberately making sure the events of the habitual occur. Observe the difference:

- Tarou wa tabako wo suu

太郎はタバコを吸う

Tarou smokes cigars. (habitual.) - Tarou wa tabako wo sutte-iru

太郎はタバコを吸っている

Tarou is smoking a cigar. (progressive.)

Tarou has been smoking cigars. (iterative.) - Tarou wa {{tabako wo suu} you ni} shite-iru

太郎はタバコを吸うようにしている

Tarou has been making [it] {so that {[he] smokes cigars}}.

Tarou has decided {to smoke cigars}.

The second sentence (sutte-iru) in the iterative meaning suffices if we need to emphasize that for a particular span of time Tarou has been doing a habit. The third sentence (you ni shite-iru) is only necessary if we need to emphasize Tarou deliberately changed habits.

In practice, with this example that would be unlikely. A more likely example would be if the habitual is negative, because then they're deliberately making sure the events don't occur:

- Tarou wa {{tabako wo suwanai} you ni} shite-iru

太郎はタバコを吸わないようにしている

Tarou has been making [it] {so that {[he] doesn't smoke cigars}}.

Tarou has decided {to not smoke cigars}.- In this sentence, we understand that Tarou has an habit of smoking, but he's deliberately trying to quit the habit by doing whatever he can to not smoke.

Another example:

- Context: guy comes take his child from a "nursery school," hoikuen 保育園.

- a... arigatou gozaimashita!!

あ・・・ありがとうございました!!

T... thank you [for everything]!!- Past tense of arigatou gozaimasu.

- sensee sayounara

せんせーさようなら

Good bye, teacher. - sayounara

さようなら

Good bye. - otonashii kara chotto dake shinpai datta kedo

おとなしいからちょっとだけ心配だったけど

[She's] quiet so [I] was a bit worried, but - Rin-chan φ tottemo ii ko ni shitemashita yo

りんちゃんとってもいい子にしてましたよ!!

Rin-chan was a very good [girl], [you see]!!- shitemashita してました is the past of shitemasu してます which is the masu ます form is shiteru してる which is shite-iru している pronounced without i い.

- The ~te-iru form is used here because Rin-chan was left in the nursery for a period of time while her parent was working, and "during the period of time" she made herself an ii ko いい子, a "good child," i.e. she behaved well.

- Since this period of time occurred in the past, the past form is also used.

~してある

Naturally, it's also possible to conjugate suru to the ~te-aru ~てある form, just like it could be done with any other causative verb.

- heya wa {kirei ni} shite-aru

部屋は綺麗にしてある

The room is clean, as result of someone having cleaned it.

The Other ~ように

The ~you ni ~ように we've seen in this article, used with eventivizers, is a phrase used to adverbialize states expressed through verbs, such as habituals and potentials. Besides this one, there's another, more general you ni ように that looks very similar.

Observe:

- neko da

猫だ

[It] is a cat. - {neko ni} naru

猫になる

To become {a cat}. - {neko no} you da

猫のようだ

[It] is like {a cat}.

[It] seems {to be a cat}. - {{neko no} you ni} naru

猫のようになる

To become {like {a cat}}.

This you よう means "like," in the sense of having similar appearance. It's spelled in kanji as you 様, homograph with the sama 様 honorific suffix. It's pretty different from the you よう we've been using with stative verbs and habituals.

- sou omou

そう思う

[I] think so. - {{sou omou} you ni} naru

そう思うようになる

[I] will become {in a way [that] {thinks so}}.

[I] will start {thinking so}.

We know this because the sentence above makes sou omou, "think so," become true, while the other one makes neko no you da, "like a cat," become true.

If they were the same you よう, then the sentence above should make true sou omou you da そう思うようだ, "it seems [I] think so," or "it's like [I] think so." This isn't the case. There is no "like" or "seems" or "appears to be" or "sorta kinda" about it.

As we've seen previously, we can conjugate ~you ni naru to ~you ni natta to make it past tense, which means there's no reason to conjugate the verbal state itself to past tense.

The ~you ni used with eventivizers is preceded by a nonpast form, never by a past form. Whenever the past form is used, we have the "like" meaning of you よう. Observe:

- tamashii ga nuketa

魂が抜けた

The soul was extracted. (literally.)

[Their] soul left [their] body.

- Expression used when someone is disheartened, distraught, in shock. Often drawn in anime.

- {tamashii ga nuketa} you da

魂が抜けたようだ

[It] seems {[their] soul left [their] body}. - {{tamashii ga nuketa} you ni} natta

魂が抜けたようになった

[They] became {in a way that looked like {[their] soul left [their] body}}.- Since the nuketa 抜けた before you よう is in past tense, the you よう can only mean "looked like."

- This is the figure of speech.

- {{tamashii ga nukeru} you ni} natta

魂が抜けるようになった

[They] became {in a way [that] {[their] soul leaves [their] body}}.- Here, nukeru 抜ける is in nonpast form. Since it's an eventive verb, this is a habitual stative predicate, which means their soul is leaving their body habitually, repeatedly.

- This is the plot of some anime like Noragami ノラガミ, in which a character is involved in some accident that changes them in a way that their soul starts coming out of their body on their own.

Sentence-Ending ~ように

Sometimes a sentence ends in ~you ni ~ように in Japanese. This can happen for multiple reasons.

Sometimes, what comes after is merely omitted, i.e. the eventivizer is elliptical.

Sometimes, what comes after is moved toward the start of the sentence. This is called a dislocation, and it generally doesn't occur with vague verbs like suru and naru, as they won't make sense at the start of the sentence.

- eakon wo chousetsu shita, {{shitsu-on ga {ni-juu-do ni} naru} you ni}

エアコンを調節した、室温が28度になるように

[I] adjusted the air conditioner, {so that {the room temperature is {28 degrees}}}.

Lastly, sometimes, when wishing for things to end up some way. This is typically seen in anime in prayers done in shrines at the end of the year. Such sentences will end in ~you ni and without an eventivizer at all.

- {{kotoshi mo {buji ni} sugoseru} you ni}

今年も無事に過ごせるように

{So that {[I] can live through this year, too, {without difficulties}}}.- buji da

無事だ

Without troubles. Without problems. Without difficulties.

Unharmed.

- buji da

Given that the sentence is still understood that it must occur in the future—in case of sentences like this, we'd be praying for it to happen through the following year—there must be an eventivizer converting the state to a future event.

It could be that "I'm praying so that this happens," in which case "I'm praying" takes the role of causative eventivizer. It could also be that we're saying "please make it happen," and we're asking some divine power to cause it for us.

~ことに Eventivized Events

The phrase ~you ni ~ように is used with eventivizers when we're talking about states, but it's also possible to eventivize events. We do this by using ~koto ni ~ことに instead of ~you ni ~ように.

This is a bit complicated, so let's start with the syntax.

- {{uso wo tsuku} you ni} naru

嘘をつくようになる

To become {in a way [that] {spews lies}}. (present habitual state.) - {{uso wo tsuku} koto ni} naru

嘘をつくことになる

To become {in a way [that] {will spew a lie}}. (future perfective event.)

Eventive verbs like tsuku, "spew," in nonpast form express either a present habitual state or a future perfective event. With ~you ni, we have the state, with ~koto ni, we have the event.

The phrase ~you ni used to eventivize verbal states always has the verb in nonpast form, by contrast, ~koto ni can also accept past events.

- *{{uso wo tsuita} you ni} naru

嘘をついたようになる

- Only valid in the "like," "as if" sense of ~you ni, e.g. "to become as if [someone] spewed a lie."

- {{uso wo tsuita} koto ni} naru

嘘をついたことになる

To become {in a way [that] {spewed a lie}}.

From the above, we know that ~koto ni accepts both past and nonpast forms, even though ~you ni only accepts nonpast, and we also know that ~koto ni accepts events even though ~you ni generally doesn't. (the exception being ~naru you ni, because naru is eventive.)

What would be the difference in meaning between them?

Basically, it has to do with the subjunctive mood, and the subjunctive has to do with alternative worlds and realities, which has to do with our assumption of facts.

We assume for a fact that certain events have occurred in the world in the past, and that certain events will occur in the world in the future. It doesn't matter why or how exactly stuff occurs, the point is that we presuppose their occurrence.

For example, we can assume as a fact that Tarou has lied in the past, or that Tarou will lie in the future. Of course, since the future hasn't occurred yet, we don't know for a fact that he will have lied in the future, but in the present we assume for a fact that he "will" do it for some reason.

Maybe he told us he was going to lie or something like that. Anyway, we assume the occurrence of the event.

What koto こと does is introduce a set of facts that differs from our presupposition.

Let's say Tarou is preparing a secret birthday party for Hanako. In order to keep the party a secret, he can't tell Hanako about it. But what if Hanako asks Tarou if he knows that today is a special day? He'll have to feign ignorance and pretend to have forgotten about her birthday.

- {{uso wo tsuku} koto ni} naru

嘘をつくことになる

It will be {in a way [that] {[Tarou] will lie}}.

[He] will [end up having to] lie.

We never assumed that Tarou "will lie" in the future, so if a situation arises in which he ends up having to lie, that proposes a new future in which Tarou "will lie."

That is, in the current world, the lie event isn't assumed to happen, but in the hypothetical, alternative world, it is.

This might sound like a very complicated explanation, but it's necessary because koto has several other uses and this is the only way to explain what's actually going on here.

In the previous example, we changed the future by assuming a new set of facts. We can also change the past by doing the same thing.

For example, imagine that Tarou said he was in his apartment watching TV yesterday at midnight, when Hanako was murdered. But then we check the cameras and see that Tarou left his apartment at 10:00pm and didn't return until after midnight. In that case:

- {{Tarou ga uso wo tsuita} koto ni} naru

太郎が嘘をついたことになる

It will be {in a way [that] {Tarou lied}}.

It would mean that Tarou lied.

Above, we assumed for a fact that Tarou told the truth. This was our presupposition. Through koto, we propose a world in which Tarou didn't tell the truth, contrary to our presupposition.

Literally every time koto ni naru is used we'll have a presupposition of events that have, will have, haven't, or won't have happened, and a proposition that contradicts that.

Notably, the past contradiction is sometimes followed by to wa とは that abbreviates to wa omowanakatta とは思わなかった, "[I] didn't think that [things would turn that way]." For example:

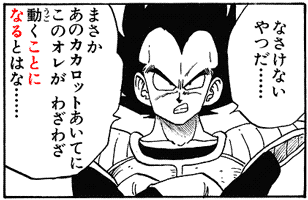

- Context: Vegeta sent his underling to fight Kakarot. His underling lost. Vegeta is perplexed.

- nasakenai

yatsu da

なさけないやつだ・・・・・・

[What a] pathetic guy.- Referring to a guy who just lost to Kakarot.

- {masaka

{{ano Kakarotto aite ni

kono ore ga wazawaza

ugoku} koto ni}

naru} towa na......

まさかあのカカロットあいてにこのオレがわざわざ動くことになるとはな・・・・・・

[I] didn't think that {[it] would end up {in such way [that] {against that Kakarot, I have to [fight]}}}.- In other words: Vegeta didn't expect he'd have "to move," ugoku 動く. He expected his underling to handle it. So he wouldn't have to act, he wouldn't have to fight Kakarot.

- However, since his underling lost, the "situation became in such way that" it's necessary for him to make a move.

- That's what koto ni naru is expressing: reality ended up in a way contrary to what was presupposed.

The past tense of naru なる can be used when the alternative reality already became the presupposition, in which case whatever is qualifying koto is the current reality already.

- {{uso wo tsuita} koto ni} natta

嘘をついたことになった

It became {in such way [that] {[he] lied}}.

It ended up so that he had to lie. (or something like that.) - {{uso wo tsuku} koto ni} natta

嘘をつくことになった

It became {in such way [that] {[he] will lie}}.

It ended up so that he will have to lie. (or something like that.)

Note that just because the assumed facts changed, that doesn't mean the future events have already occurred.

When the past form is used (tsuita) it means it already occurred in the past, but when the nonpast is used (tsuku) it means that it has yet to happen, even though it's already been confirmed and assumed as a fact that it's going to happen.

As one would expect, since we're able to say koto ni naru ことになる, koto ni natta ことになった, we're also able to say koto ni suru ことにする, and koto ni shita ことにした.

In this case, we're changing what events occur. We're causing the change, rather than simply noticing it. This generally translates to "decide."

- {{uso wo tsuku} koto ni} suru

嘘を付くことにする

[I] will decide {to lie}.

However, we could also be changing the facts by fabricating them. An obvious example:

- {{Tarou ga shinda} koto ni} suru

太郎が死んだことにする

[I] will make [it] so [that] {Tarou died}.- In the sense of fabricating Tarou's death. We'll make it appear that he died. Everybody will assumed his death actually occurred, because we made it so.

Once again, the same function is available in the past:

- {{Tarou ga shinu} koto ni} shita

太郎が死ぬことにした

[I] decided [that] {Tarou will die}.

[I] made [it] {so [that] {Tarou will die}}.- This can have two meanings. Either I decided that Tarou will die for real in the future, as opposed to letting him live, or I decided to fabricate a story in which Tarou will die. In both cases, the event of Tarou's death would be assumed as a fact.

A last interesting situation is that in which someone decides to lie to themselves about what actually happened. For example:

- sore wa {{minakatta} koto ni} shita

それは見なかったことにした

About that: [I] made [it] {so that {[I] didn't see [it]}}.

I decided that I didn't see that.

I'll pretend I didn't see that.

Due to the "end up so" and "decide to do so" meanings of koto ni naru and koto ni suru, it's also possible to use them with the habitual predicates. For example:

- {mai-nichi jogingu suru} koto ni natta

毎日ジョギングすることにした

It ended up so that {[I] jog every day}.

It ended up so that I'll have to jog every day. - {mai-nichi jogingu suru} koto ni shita

毎日ジョギングすることにした

[I] decided {to jog every day}.

The function is the same: we're introducing a world in which a given event happens that differs from the current world.

The difference between koto ni and you ni is that you ni merely says "it will be so," or "we'll make it so," while koto ni assumes at least one alternative world: we had the option to jog every day or to do something else, and we chose (or it ended up so that) we'll jog every day.

~ために Purposes

As we've seen, ~you ni can only be used in nonpast form with stative predicates. This is important because, as mentioned a number of times, statives only express the present tense in nonpast form, not the future tense.

In the Japanese tense system, the tense of a subordinate clause is typically relative to the tense of the matrix. When the tense of the subordinate is present, it would occur simultaneously with the matrix.

- {{oyogeru} you ni} naru

泳げるようになる

To become able to swim.- When naru occurs, oyogeru simultaneously becomes true.

Since naru is eventive, {~naru} you ni has the relative clause {~naru} set in the future from the eventivizer.

For example(于, 1998:130):

- {{kanja ga {shizuka ni} naru} you ni}, isha wa chinsei-zai wo chuusha shita.

患者が静かになるように、医者は鎮静剤を注射した。

{So that {the patient would {be quiet}}}, the doctor injected the sedative.- In this sentence, "would" occurs after "injected."

Causative usage like the above allows ~you ni to be used in a way that says "to do something so that something else occurs." Except that "something else" must be a state or a change of state.

When something else isn't a state, the phrase ~tame ni ~ために, "for the purpose of," "in order to," is used instead.

For example(于, 1998:128):

- *watashi wa, {{nihongo wo benkyou suru} you ni}, nihon ni kita

私は、日本語を勉強するように、日本に来た

The sentence above only makes sense if benkyou suru were habitual, but what we want is the perfective:

- watashi wa, {{nihongo wo benkyou suru} tame ni}, nihon ni kita

私は、日本語を勉強するために、日本に来た

I came to Japan {in order to {study Japanese}}.

To elaborate, ~tame ni says: "I will study Japanese, so I came to Japan." Meanwhile, ~you ni could only mean: "coming to Japan is how I caused myself to study Japanese habitually."

Similarly(adapted from 于, 1998:131–132):

- *kare wa, {{oyogi wo narau} you ni}, mai-nichi renshuu shite-iru.

彼は、泳ぎを習うように、毎日練習している。 - kare wa, {{oyogi wo narau} tame ni}, mai-nichi ni renshuu shite-iru.

彼は、泳ぎを習うために、毎日練習している。

{So that {[he] will learn to swim}}, he has been practicing every day.

He has been practicing every day {in order {to learn to swim}}. - kare wa, {{(kare ga) oyogeru} you ni}, mai-nichi renshuu shite-iru

彼は、(彼が)泳げるように、毎日練習している。

{So that {(he) is able to swim}}, he has been practicing every day.

He has been practicing every day {in order {to be able to swim}}.

As you can see above, the usage is practically identical, the only difference is that ~you ni is used with verbal states, while ~tame ni is used with events.

It's worth noting that just like ~you ni has other uses, ~tame ni has other uses too. For example, it can be used to say for whom something was made.

- {kodomo no tame ni} tsukurarete-iru

子供のために作られている

[It] was made {for children}.

Non-State Adverbs

In some cases, the adverb modifying the eventivizer isn't the adverbial form of a state, but simply an adverb that's modifying the eventivizer. Observe the examples below:

- chotto {samuku} naru

ちょっと寒くなる

It will become {cold} a bit.

It will become a bit cold.

- Here, chotto modifies naru.

- {{sonna ni} samuku} naranai. chotto naru.

そんなに寒くならない。ちょっとなる。

It won't become {{that much} cold}. It will become a bit.- Here, chotto modifies naru, again.

In the examples above, chotto isn't a state, it's a quantifier. It's either modifying naru or modifying samuku implicitly. It can't be a state, because it's lexically an adverb, rather than the adverbial form of a lexical adjective.

Such modifiers aren't restricted to lexical adverbs. For example:

- sugu da

すぐだ

[It] is immediate. - sugu ni samuku natta

すぐに寒くなった

[It] "immediately became" cold. (correct.)

[It] became "immediately cold." (wrong.)- #sugu ni samui

すぐに寒い

#[It] is immediately cold. - Makes no sense at all, so sugu ni and "immediately" are modifying naru and "become."

- By contrast:

- hijou ni samui

非常に寒い

[It] is unusually cold. - Makes sense, so:

- hijou ni samuku natta

非常に寒くなった

[It] became unusually cold. (correct.)

[It] unusually became cold. (I guess this is technically possible, too, although unlikely.)

- #sugu ni samui

An interesting situation occurs in this sentence:

- {suki ni} suru

好きにする

To do as [one] likes.

To do as one pleases.

To do whatever you want.

In this sentence, suru する isn't an eventivizer, even though the syntax is identical to the eventivizer. Instead, suru means "to do" here, and suki da 好きだ, "liked," is an adverb modifying suru.

Also note that suki da is an emotional state of a person. As we've seen previously, we need ~you ni if the situation is caused indirectly, and we can't change the emotion or mental state of someone directly. We could say, for example:

- {{suki ni naru} you ni} saimin-jutsu wo kaketa

好きになるように催眠術をかけた

{So that {[they] like [me]}}, [I] cast upon [them] a hypnosis-technique.

I hypnotized them so that they'd fall in love with me.

Pronouns

The demonstrative adverbial pronouns kou, sou, aa, dou こう, そう, ああ, どう can be used with eventivizers. These translate to "like this," "like that," and "like how," respectively.

They're basically kono, sono, ano, dono この, その, あの, どの plus ~you da, so it makes sense they work with eventivizers that can follow ~you ni.

- kono you da. ano you da.

このようだ。あのようだ。

This way. That way.

Like this. Like that. - kou. aa.

こう。ああ。

Observe the examples below:

- watashi wa {ano baka no you ni} naritakunai

私はあのバカのようになりたくない

I don't want to become {that idiot's way}.

I don't want to become {like that idiot}. - watashi wa {ano you ni} naritakunai

私はあのようになりたくない

I don't want to become {that way}.

I don't want to become {like that}. - watashi wa aa naritakunai

私はああなりたくない

The verbs naru and suru are often used with these pronouns, specially with the interrogative dou, however, their usage appears to be only loosely connected the concept of turning states into events, even if the two verbs remain an ergative verb pair nonetheless.

Other Notes

For the sake of reference I'll include some thoughts on it here which I'm not really sure are correct.

First, note that all adjectives are fundamentally related to the verb aru ある.

This verb is combined with de で to form de aru である, which is contracted to the da だ copula. Its past form, de atta であった, is contracted to datta だった.

The past form of i-adjectives, ~katta ~かった, is a contraction of ~ku atta ~くあった. The pattern ~ku aru ~くある is also possible, but rarely occurs.

In both cases, aru ある is analyzed as a hojo-doushi 補助動詞 auxiliary verb, and it would be a stative verb, lacking futurity on its own.

It makes sense to think that de aru である, ~ku aru ~くある would be a stative copula, ni naru になる, ~ku naru ~くなる would be eventive variant, and ni suru にする, ~ku suru ~くする would be the causative variant.

More fundamentally, aru, naru, and suru are semantically linked somehow, and the meaning of one can be understood from the other.

For example, when used with dou どう:

- dou datta? (or de atta)

どうだった? (or であった)

How was it?

How were things? - dou da? (or de aru)

どうだ? (or である)

How is it?

How are things? - dou naru?

どうなる?

How will things become?

How will things turn out?- The future tense can only be achieved through naru, because aru is stative.

- dou natta?

どうなった?

How did things become?

How did things turn out?- If naru is conjugated to the past, we presuppose a change occurred in the past, that is, things "turned out" somehow, rather than simply "were" somehow.

- dou natte-iru?

どうなっている?

How have things turned out?

What is happening?

What is going on? - dou suru?

どうする?

How will [you] act?

What are [you] going to do?

What should [I] do?- If dou naru refers to some state forming in the future, dou suru must refer to causing some state to form in the future. Whatever you suru, "do," causes things to naru, "become," somehow.

- dou shita?

どうした?

How did [you] act?

What happened to [you]?- This phrase, too, should follow the same pattern, however, it's normally used to ask what's translated to English as "what happened to you?" rather than "what did you do?"

- dou shite-iru?

どうしている?

How are [you] doing?- Similarly, this phrase is used to ask how someone is currently.

Idiosyncrasies like dou shita make it hard to figure whether the meanings of these words really relate or not, but in principle they should.

- dou shite kou natta?

どうしてこうなった?

Why did things turn out this way?- The phrase dou shite is often translated to "why," but since it's the te-form of dou suru, it should be a connective here.

- Literally, the sentence says "how did [you] act so that things became this way?"

- Or, less literally: "what did [you] have to do for things to end up like this?"

- sore ga dou shita?

それがどうした?

So what?- Literally, this sentence should mean "that changed [things] how?"

- In anime, it's typically used to ignore a statement made trying to stop you.

- What about it? So what?

- In English, the closest thing would be:

- That changes nothing!

The verb aru is sometimes used with the meaning of "occur," rather than "is" or "exists."

The verb naru 成る can mean for something "to concretize" in the future, with the spelling naru 生る meaning "to come to fruition," minoru 実る, and the spelling naru 為る meaning "to change."[「成る」「為る」「生る」の違い - kanjitisiki.com]

The verb nasu 成す, which means "to accomplish" something in the future, nasu 生す, "to bear fruit," "to give birth to," "to fabricate," and nasu 為す, "to act," "to perform."[「成す」「為す」「済す」「生す」の違い - kanjitisiki.com]

There are many cases where nasu is replaced by suru. Given that naru and nasu are very similar morphologically, I guess naru and nasu are the original ergative verb pair, and suru forms a pair with naru only because it replaces nasu.

Another meaning of aru, when used in double subject constructions, is to say someone "has" something. In this sense, naru should mean "won't have."

- nani ga atta?

何があった?

What happened?

What occurred? - nani ga naru?

何がなる?

What will happen?

What will become?- This sentence is basically only used in modern Japanese to say "what good will come out of that?!"

- nani wo suru?

何をする?

What will [you] do?- The phrase dou suru is used to ask "what are you going to do?" in general, while nani wo suru is only used when asking about a specific action, e.g. when someone looks like they're right about to do something.

- nani wo shite-iru

何をしている?

What are [you] doing?

Although nani ga naru isn't normal in Japanese, there are multiple examples of ga naru being used as the future variation of aru, specially in the form ~ga naranai がならない.

- gaman ga aru

我慢がある

To have endurance. (present)

To endure. To live with [something not good enough].- Note: gaman ga is the small subject of a double subject construction, given that it must be someone's (i.e. the large subject's) endurance we're talking about here.

- gaman ga naru

我慢がなる

Endurance will concretize.

Will have endurance. (in the future.) - gaman ga naranai

我慢がならない

Endurance won't concretize.

To not have endurance. (in the future.)

Won't be endure it [any longer].- watashi wa anata ni gaman ga naranai

私はあなたとに我慢がならない

I won't have [anymore] patience for you.

I can't endure you [any longer]. - Sentences such as these typically omit the ga が, e.g. gaman naranai 我慢ならない.

- watashi wa anata ni gaman ga naranai

- yudan ga naranai

油断がならない

Negligence won't concretize.

Won't be careless. - shin'you ga naranai

信用がならない

Trustworthiness won't concretize.

Won't be trustworthy. - {shin'you no aru} hito

信用のある人

A person [who] {has a good reputation}.

A person [who] {is trustworthy}. - {shin'you no naranai} hito

信用のならない人

A person [who] {won't be trustworthy}.

A person [whom] {can't be trusted}.

Another use of naru なる worth noting is the one after ~te wa ~ては, which is contracted to ~cha ~ちゃ. For example, sometimes you see in anime phrases like:

- makecha dame!

負けちゃ駄目!

Don't lose! - makete wa dame

負けては駄目

What the sentences above say, basically, is that "losing is bad," therefore, you shouldn't do it: "don't lose."

A more literary sounding variant would be:

- makete wa naranai

負けてはならない

From what we've seen so far, this sentence should mean, literally, that "losing won't concretize," asserting that a future in which the losing event happens won't come to fruition.

As it turns out, it's possible to say this in the affirmative and without the wa は particle.

- makete naru mono ka!

負けてなるものか!

As it [I] would lose!- Note: mono もの is a sentence ending particle in this rhetoric question. It's often contracted to mon もん.

- nigeru mon ka!

逃げるものか!

As it [I] would run!

If makete aru 負けてある means "to have lost" in the sense that someone deliberately "lost," then makete naru 負けてなる should mean to deliberately lose in the future. However, this isn't the case.

The phrase makete naru is used by people who want to win, so they're referring to "ending up losing without wanting to," and not "deliberately losing," so this ~te naru isn't related to ~te aru.

Furthermore, if it was related, then there would be a makete suru 負けてする to serve as a causative, but there isn't. Sometimes you see phrases like:

- kate wa shinai

勝てはしない

[He] won't be able to win.

But that's not a te-form of katsu 勝つ, "to win," which would be katte 勝って, that's the ren'youkei of the potential verb kateru 勝てる, "to be able to win."

Given this, the naru in ~te naru wouldn't be an auxiliary verb like the aru in ~te aru but a main verb instead. I have no idea what subject it's supposed to be predicating, but I suppose you could rephrase it as:

- makete nani ga naru?!

負けて何がなる?!

What will [it] be if [you] lose?

What good will come out of losing? - makete wa nanimo naranai!

負けては何もならない!

Nothing will come out of losing!

- Note: nanimo naranai is nani ga naru with ga replaced by mo, while:

- nan-ni-mo naranai

何にもならない

[Something] won't become anything. - Would be ~ni naru instead.

- makete wa {ii koto ni} naranai

負けてはいいことにならない

If [you] lose [it] won't turn out {good}.

Nothing good will come out of losing.

Due to naru often showing up as naranai, it's hard to get a clear picture of what it's supposed to mean, but I guess the above could be right. For example:

- sou omoete nanimo naranai

そう思えて何もならない

Nothing good will come out of feeling that way. - sou omoete naranai

そう思えてならない

If not, then it could be the speaker has a plan or goal that won't be concretized if they do something.

No comments: