The Japanese language is often said to have only two irregular verbs: suru する, "to do," and kuru 来る, "to come," which are also called "group 3 verbs," among the three groups of verbs in Japanese, the other two being godan verbs and ichidan verbs, whose conjugation would be regular.

Besides those, the words aru ある, nai ない, yoi よい, ii いい, and iku 行く also feature irregularities to watch out for. So I'm listing all of them here.

Grammar

Japanese conjugation is extremely regular, unlike the English conjugation, which is a disgusting mess. Most verbs forms are created by using suffixes called jodoushi 助動詞. Observe:- kiru

着る

To wear. (non-past) - kita着た

Wore. To have worn. Did wear. (past.) - kinai

着ない

To not wear. (negative.) - kimasu

着ます

To wear. (polite form.)

Above, the stem morpheme of the verb "to wear," ki~ 着~, remains the same across its different forms.

By contrast, the verb kuru 来る can have the vowel of its first syllable changed, giving multiple readings for the kanji 来. For example, the past form would be kita 来た, which starts with ki き, instead of ku く.

Conjugation

来る

For reference, the conjugation of the irregular verb kuru 来る:- kuru 来る(くる)

To come. (non-past.)- Here, 来 is read ku く.

- kita 来た(きた)

Came. To have come. Did come. (past.)- Here, 来 is read ki き.

- konai 来ない(こない)

To not come. (negative.)- Here, 来 is read ko こ.

- kimasu 来ます(きます)

To come. (polite form.) - kite 来て(きて)

To come and. (te-form.) - koi 来い(こい)

Come! (imperative form.) - koyou 来よう(こよう)

Let's come. (volitional form.) - korareru 来られる(こられる)

To be able to come. (potential form, and passive form, too.) - koreru 来れる(これる)

To be able to come. (potential form, see: ら抜き言葉.) - kosaseru 来させる(こさせる)

To make come. (causative form.)

Although the stem of the irregular verb is irregular, the suffixes remain regular. For example, the negative past form is konakatta 来なかった, "didn't come," and the polite past form is kimashita 来ました, "came." Just as you'd expect in any other verb.

Also, it's not really fair to say that the stem is irregular, since the k~ consonant stayed the same through all conjugations.

It's more appropriate to say that kuru is a sandan 三段, "three-column," verb, since its first syllable ranges across three vowels: ku-ki-ko くきこ.

The technical term would be ka-gyou henkaku katsuyou カ行変格活用, "ka-row irregular conjugation."

する

For reference, the conjugation of the verb suru する, too:- suru する

To do. - shita した

Did. - shinai しない

Doesn't do. - shimasu します

To do. (polite form.) - shite して

To do and. (te-form.) - shiro しろ

seyo せよ

Do [it]! (imperative form.) - shiyou しよう

Let's do. (volitional form.) - dekiru できる

To be able to do. (potential form.) - sareru される

To be done. (passive form.) - saseru させる

To make do. (causative form.)

There are a few things worth noting about.

First, the irregular verb suru する and the irregular verb kuru 来る aren't even regular between themselves.

For example, the negative form of kuru 来る is konai こない, the stem syllable changes to the ~o vowel, but for suru する it's shinai しない, which ends in the ~i vowel. So they're two completely separate irregular verbs.

Second, you may have noticed that for some ungodly reason the word dekiru できる is written where the potential form of suru する was supposed to go. Surely, ,this must be a typo, right? Because dekiru できる has literally nothing to do with suru する.

This isn't a typo.

- ryouri wo suru

料理をする

To do the cooking. - ryouri suru

料理する

To cook. - ryouri wo dekiru

料理をできる

To be able to do the cooking. - ryouri dekiru

料理できる

To be able to cook.

Can cook.

The verb suru する is so irregular that its potential form is literally a whole different verb. I mean, seriously, dekiru 出来る by itself means, among other things, "to be made of."

- karada wa tsurugi de dekite-iru

体は剣で出来ている

[My] body is made of swords.

More literally, dekiru できる means "to realize," "to accomplish," "to finish (making)" something. If you can realize the act of cooking, it means you're able to cook.

Again, derived forms are regular. The past potential form of suru する is the past form of dekiru できる, in other words: ryouri dekita 料理できた, "was able to cook."

Beware: the verb suru する has dozens of different uses. In all of them, dekiru できる is the potential form.

- mono ni suru

ものにする

To make it one's possession.

[I] will make [it] mine. - mono ni dekiru

ものにできる

To be able to mono ni suru.

To be able to make it one's possession. - jiyuu wo te ni suru

自由を手にする

To put freedom in one's hand. (literally.)

To acquire freedom.

To obtain freedom. - jiyuu wo te ni dekiru

自由を手にできる

To be able to obtain freedom.

By the way, if the potential form was regular, it would be the mizenkei form, se~, plus ~rareru, so serareru せられる. In fact, this form was once used in Japanese:

- ai suru

愛する

To love. - ai serareru

愛せられる

To be able to love.

Nowadays, people don't say this. They say aiseru 愛せる, as if aisu 愛す were a godan verb.

Like with kuru, there's a technical term for the suru verb conjugation: sa-gyou henkaku katsuyou サ行変格活用, "sa-row irregular conjugation.".

This would also apply to ~zuru ~ずる verbs, which are simply suru with rendaku 連濁.

- meizuru (mei suru)

命ずる

To order. - meijita (mei shita)

命じた

Ordered.

ある

The verb aru ある, "to exist," is generally regular, except for one thing: its negative form is nai ない, "nonexistent." This only happens with the plain negative form. The polite negative form is arimasen ありません, as you'd expect to derive from the polite form arimasu あります.- kibou ga aru 希望がある

kibou ga arimasu 希望があります

Hope exists.

There is hope. - kibou ga nai 希望がない

kibou ga arimasen 希望がありません

Hope is nonexistent. Hope doesn't exist.

There is no hope.

Now, you may be wondering how does it make sense that the negative form of a verb is an i-adjective. Well, technically, the negative form of every verb in Japanese is a kind of an i-adjective, since they all end in nai ない anyway, so don't worry about it.

Once again, we have a verb that's used in a bunch of extremely weird ways, which is irregular on top of it. To begin with, it can be used to talk about possessions instead:

- okane ge aru

お金がある

Money exists [in possession].

To have money. - okane ga nai

お金がない

To not have money.

Such sentences, which refer to the existence or non-existence of something about someone, are a kind of double-subject construction. At first glance they look pretty normal, except that some of them are extremely complicated by themselves:

- watashi niwa kankei aru

私には関係ある

There's a relationship to me.

That has to do with me. - watashi niwa kankei nai

私には関係ない

That has nothing to do with me.

- watashi wa {manga wo yonda} koto ga aru

私は漫画を読んだことがある

I have the experience [that is] {to read manga}.

I've read manga before. - watashi wa {manga wo yonda} koto ga nai

私は漫画を読んだことがない

I don't have the experience [that is] {to read manga}.

I've never read manga before.

The irregularity also happens when aru ある is used as a hojo-doushi 補助動詞:

- kaite-aru

書いてある

To have been written. - kaite-nai

書いてない

To not have been written.

- neko de aru 猫である

neko de arimasu 猫であります

[It] is a cat. - neko de wa aru 猫ではある

neko de wa arimasu 猫ではあります

(same meaning as above. See: wa は particle.) - neko de nai 猫でない

neko de arimasen 猫でありません

[It] is not a cat. - neko de wa nai 猫ではない

neko de wa arimasen 猫ではありません

(same meaning as above.) - neko janai 猫じゃない

neko ja arimasen 猫じゃありません

(same meaning as above, this is a contraction.)

- kawaiku aru 可愛くある

kawaiku arimasu 可愛くあります

[It] is cute. - kawaiku nai 可愛くない

kawaiku arimasen 可愛くありません

[It] is not cute.

無い

The i-adjective nai 無い is kind of irregular. That's only because, when using the suffix ~sou ~そう with it, the suffix is attached to its sa-form instead of the stem.For example, while a normal adjective would look like this:

- kore ga oishii

これが美味しい

This is delicious. - kore no oishi-sa

これの美味しさ

The deliciousness of this. - kore ga oishi-sou da

これが美味しそうだ

This seems delicious.

The nai 無い adjective looks like this:

- kare wa okane ga nai

彼はお金が無い

Money is nonexistent is true about him.

His money doesn't exist.

He doesn't have money. - kare no okane no na-sa

彼のお金の無さ

The nonexistentialness of his money.

His lack of money. - kare wa okane ga na-sa-sou da

彼はお金が無さそうだ

He doesn't seem to have money.

The same applies to nai 無い as a hojo-keiyoushi 補助形容詞.

- oishiku-na-sa-sou da

美味しくなさそうだ

[It] doesn't seem delicious.

However, when nai ない is a jodoushi 助動詞, the sa さ isn't necessary.

- ame ga furanai

雨が振らない

Rain doesn't rain.

It doesn't rain. - ame ga furana-sou da

雨が振らなそうだ

It seems rain doesn't rain.

It seems it won't rain.

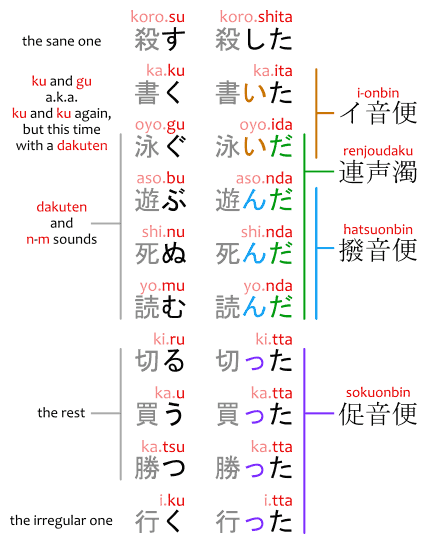

行く

The verb iku 行く conjugates differently from other godan verbs ending in ~ku ~く. The past form ends in tta, and the te-form ends in tte. Observe:- kiku

聞く

To heard. - kiita

聞いた

Heard. - kiite

聞いて

Hear [me]. (imperative.)

- iku

行く

To go. - itta

行った

Went. - itte

行って

Go. (imperative.)

Source: japanesewithanime.com (CC BY-SA 4.0)

いい

The i-adjective ii いい is the most irregular adjective in the whole Japanese language. Observe:- ii

いい

Good. - yokatta

よかった

Was good. - yokunai

よくない

Is not good. - yoku

よく

Well [done]. - yokattara

よかったら

If were good. - yokereba

よければ

If be good. - yokarou

よかろう

Very well.

As you can see above, every one of its inflections is irregular.

In fact, it's actually the opposite: the actual adjective is yoi よい, which means the same thing as ii いい, "good," but in its predicative form and attributive form, the adjective ii いい is preferred over yoi よい.

The real past form of ii いい would be ikatta いかった, and its negative would be ikunai いくない.

いい. It seems that, in some regions of Japan, such words are actually used. In most of Japan, however, yokatta, yokunai, are used instead.[ 形容詞の「よい」と「いい」はどう違う?- alc.co.jp, accessed 2019-11-02]

This is particularly important since ii いい has some weird functions, like:

- tabete ii?

食べていい?

Eating, good?

Is it alright to eat it?

Can I eat it? - yokunai

よくない

Not good.

It's not alright.

No, you can't.

よい

Like the nai 無い adjective, yoi 良い also gets the ~sou ~そう added to its sa-form instead of its stem.- kimochi-ii

気持ちいい

Feeling-good.

Pleasant. - kimochi-yo-sa-sou da

気持ちよさそうだ

It looks like it feels good.

It looks like it's pleasant.

This article is an absolute godsend, well written, clear, funny and extensive, with simple to the point examples. THANK YOU SO MUCH!!

ReplyDeleteThis is more than useful. Very valuable as a reference for a beginner student like myself. Thank you and I hope you'll have more resources like this in the future.

ReplyDelete