For example: tabete-iru 食べている, "to be eating," has the verb iru いる, "to exist," as a support verb for teberu 食べる, "to eat."

List

Here's a list of hojo-doushi for reference:- -te-iru

~ている

To be doing [the verb].

To be [in a state described by the verb].- koroshite-iru

殺している

To be killing. - shinde-iru

死んでいる

To be dead. - See also: ergative verb pairs.

- Usage as main verb:

- koko ni iru

ここにいる

[He] is here. (person or animal.)

- koroshite-iru

- ~te-aru

~てある

To have been done [the verb].- kaite-aru

書いてある

To be written. - kaite-nai

書いてない

To not be written. - Usage as main verb:

- koko ni aru

ここにある

[It] is here. (thing.)

- kaite-aru

- ~te-oku

~ておく

To do [the verb] for later.- kaite-oku

書いておく

To write [something] for later. To take a memo. - oboete-oku

覚えておく

To remember [something] for later. - Usage as main verb:

- koko ni oku

ここに置く

To place [it] here. - koko ni oite-oku

ここに置いておく

[I] will leave [it] here for later.

- kaite-oku

- ~te-miru

~てみる

To try to do [the verb]. To do [the verb] and "see" the outcome.- yatte-miru

やってみる

[I] will try to do [it]. - kare to hanashite-miru

彼と話してみる

[I] will try talking with him. - mou ichido itte-miro

もう一度言ってみろ

SAY [THAT] ONE MORE TIME AND SEE WHAT HAPPENS. - Usage as main verb:

- sora wo miru

空を見る

To see the sky.

To look at the sky.

- yatte-miru

- ~te-ageru

~てあげる

To do [the verb] as a favor for someone.- oshiete-ageru

教えてあげる

[I] will teach [you] as a favor for [you]. - Usage as main verb:

- te wo ageru

手を上げる

To raise [one's] hand.

- oshiete-ageru

- ~te-kureru

~てくれる

Same meaning as ~te-ageru, but implies the receiver is inferior to the giver. Consequently, it's not used when giving things to other people, because that's rude, it's only used when receiving things from others, because then it sounds humble.- oshiete-kureru?

教えてくれる?

Will [you] teach [me]? - Usage as main verb:

- banana wo kureta

バナナをくれた

[He] gave [me] a banana.

- oshiete-kureru?

- ~te-yaru

~てやる

Same meaning as the two words above, but not polite.- oshiete-yaru!

教えてやる!

[I] will teach [ya]! - Usage as main verb:

- esa wo yaru

餌をやる

To give animal-food [to an animal].

- oshiete-yaru!

- ~te-sashi-ageru

~て差し上げる

A humble variant of ~ageru.- oshiete-sashi-agemasu

教えて差し上げます

[I] shall teach [you].

- oshiete-sashi-agemasu

- ~te-morau

~てもらう

To have [someone] do [the verb] for you.- oshiete-morau

教えてもらう

[I] will have [you] teach [me]. - Usage as main verb:

- okane wo moratta

お金をもらった

[I] received money [from him].

- oshiete-morau

- ~te-itadaku

~ていただく

Same meaning as ~te-morau, but polite.- oshiete-itadakemasu ka?

教えていただけますか

May [I] have [you] teach [me]? - Usage as main verb:

- zenbu itadaku

全部頂く

[I] will take everything.

- oshiete-itadakemasu ka?

- ~te-iku

~ていく

To do [the verb] going away from you.- mado kara tonde-itta

窓から飛んでいった

[He] jumped from the window. (and I'm inside the room where he escaped from.) - Usage as main verb:

- gakkou ni iku

学校に行く

To go to school.

- mado kara tonde-itta

- ~te-kuru

てくる

To do [the verb] coming toward you.- mado kara tonde-kita

窓から飛んできた

[He] jumped from the window. (and landed right in front of me, outside the building.) - Usage as main verb:

- gakkou ni kuru

学校に来る

To come to school.

- mado kara tonde-kita

- ~te-shimau

てしまう

To end up doing [the verb] regrettably, by accident.- shukudai wo wasurete-shimatta

宿題を忘れてしまった

[I] forgot the homework. - {mite wa ikenai} mono wo mite-shimatta

見てはいけないものを見てしまった

[I] saw something [that] {[one] shouldn't see}.

I ended up seeing something that shouldn't be seen.

- shukudai wo wasurete-shimatta

Grammar

Generally speaking, support verbs are said to originate in normal verbs that lose their original meaning when used as auxiliaries.For example, miru 見る means "to see," but when used as a support verb, ~te-miru ~てみる, it means "to try."

Some support verbs don't really "lose" their original meanings, since the normal verb version already means something very similar, if you think really hard about it.

The point is: there's a distinction to be made between the support verb, and the normal verb the auxiliary originates from.

Conjugation

Support verbs can be conjugated just like any other verb.- kangaete-miru

考えてみる

[I] will try thinking [about it]. (non-past.) - kangaete-mita

考えてみた

[I] have tried thinking [about it]. (past.)

The main verb and support verb aru ある is particularly problematic, since its negative form is irregular: the adjective nai ない is used instead.

- okane ga aru

お金がある

To have money. - okane ga nai

お金がない

To not have money. - haratte-aru

払ってある

To have been paid. - haratte-nai

払ってない

To not have been paid.

Note: most of the time, te-nai isn't the negative form of te-aru, but the negative form of te-iru instead. This happens because te-inai can be contracted to te-nai, and te-iru is more common than te-aru.

If the sentence must be polite, the support verb is conjugated to its polite form, not the main verb.

- kangaete-mimasu

考えてみます

[I] will try thinking [about it]. - *kangaemashite-miru

考えましてみる

(wrong.)

On the other hand, if the sentence must be causative, or in the passive voice, the main verb is normally conjugated to its causative form, or passive form, not the support verb.

- tabete-iru

食べている

To be eating.

[He] is eating. - *tabete-irareru

食べていられる

(wrong.) - taberarete-iru

食べられている

To be being eaten.

[He] is being eaten. (by a monster)

- *tabete-isaseru

食べていさせる

(wrong.) - tabesasete-iru

食べさせている

To be causing to eat.

To be forcing [someone] to eat [something].

To be letting [someone] eat [something].

The above happens because the support verb is modifying the conjugated main verb: if tabesaseru means "to force [someone] to eat," then tabesasete-iru must mean "to be forcing [someone] to eat."

There are cases where the support verb is conjugated to causative or pasisve instead.

With iru いる, this happens because iru いる means something is in a given state, like the state of "eating" something, of "being eaten," or even of "forcing to eat." If iru いる is conjugated to causative, you get "to cause someone to be in a certain state." For example:

- ikiru

生きる

To live. - ikite-iru

生きている

To be in the a state you can call "living."

To be alive. - ikite-isaseru

生きていさせる

To cause [someone] to be in a state you can call "living."

To let [someone] be alive.

To let [someone] live. To not let [someone] die.

Another situation is when the support is conjugated to the passive form because the sentence is a suffering passive. For example:

- hanashite-kuru

話してくる

To come and talk.- When someone approaches you to start a conversation.

- hanashite-korareru

話してこられる

[He] came talk [to me], [and I didn't like that].

A support verb can attach to another support verb.

- yatte-mite-iru

やってみている

To be trying to do [it]. - kaite-oite-ageru

書いておいてあげる

[I] will write [it] for later for [you].

In particular, the support verbs that mean "to give" or "to do a favor for" can actually be combined together:

- oshiete-agete-kureru?

教えてあげてくれる?

Will [you] teach [them] for [them] for [me]?- Here, oshiete-agete is asking someone to oshiete someone else, and in doing that, they're doing a favor for this someone else.

- Added to this, kureru implies it's also a favor for the speaker themselves.

- In other words, if the listener does a favor for a third party, that will be doing a favor for the speaker.

- For example: will you teach that kid how to play the piano for me? Teaching is a favor for that kid, and teaching that kid is a favor for me, it's my request.

Contractions

A number of support verbs feature contractions.- wasurete-shimau

忘れてしまう

To have forgot. - wasurete-chimatta

忘れてちまった

(same meaning.) - wasurecchatta

忘れっちゃった

(same meaning.)

In particular, ~te-iru ~ている and ~te-iku ~ていく can be contracted to ~te-ru ~てる and ~te-ku ~てく respectively. This removal of ~i ~い is extremely common in ~te-iru ~ている and even has a name: i-nuki-kotoba い抜き言葉.

- omae wa mou shinde-iru

お前はもう死んでいる

You're already dead. - omae wa mou shinderu

お前はもう死んでる

(same meaning.)

The ~i ~い is also removed in its conjugations. Including, of course, the negative one:

- shinde-inai

死んでいない

[He] isn't dead. - shindenai

死んでない

(same meaning.)

- tabete-inai

食べていない

[He] hasn't eaten. - tabetenai

食べてない

(same meaning.)

As you can see above, ~te-inai ~ていない can be contracted to ~te-nai ~てない. This is particularly confusing since the negative form of ~te-aru ~てある is, also, ~te-nai ~てない.

This means that ~te-nai ~てない can be either the contraction of the negative of ~te-iru ~ている or the negative of ~te-aru ~てある. Most of the time, it's the contraction, simply because ~te-iru, and its negative form are more common than ~te-aru.

は Insertion

All support expressions can have the wa は particle come between the main inflectable and the support inflectable. Observe below:- tabete wa iru

食べてはいる

Eating, [he] is. - kaite wa aru

書いてはある

Written, [it] is.

These are specially used when you need a contrastive wa は.

- oboete-oku

覚えておく

[I] will remember [it] for later. - oboete wa oku kedo

覚えてはおくけど

[I] will remember [it] for later, but... (I won't do something else.)

With the te-form of the da だ copula, which is the de で copula, the only support verb allowed is aru ある. However, this combination, de aru である, works different from the usual ~te aru ~てある.

Basically, de aru である is an affirmative copula. Since the negative form of aru ある is nai ない, that means the de nai でない is would be the negative copula.

- futsuu de-aru

普通である

[It] is normal - futsuu de-nai

猫でない

[It] isn't normal.

In practice, de nai でない is mostly used attributively. In the predicative, de wa nai ではない is used instead, or its contraction: janai じゃない.

- {futsuu de-nai} hito

普通でない人

A person [that] {isn't normal}. - sono hito wa futsuu de wa nai

その人は普通ではない

That person, normal, isn't. (but they may be something else.)

Since de wa nai ではない exists, it makes sense that de wa aru ではある exists, too. Observe the contrastive examples below:

- kirei de wa aru

綺麗ではある

Pretty, [it] is. (but it's expensive.) - kirei de wa nai

綺麗ではない

Pretty, [it] isn't. (but it's cheap.)

These are particularly important because the aru ある support verb can be attached to i-adjectives, too, and with similar meaning. Except that, in this case, the support verb is attached to the adverbial form. Observe:

- kawaiku wa aru

可愛くはある

Cute, [it] is. - kawaiku wa nai

可愛くはない

Cute, [it] isn't.

Since what we're doing is adding a wa は particle between the main inflectable and the support expression, it makes sense to think that we can also remove the wa は particle. However, with i-adjectives, the situation is more awkward.

Basically, kawaiku-aru 可愛くある would mean literally "exists cutely," or, less literally, "is cute," but just kawaii 可愛い by itself already means "is cute." Therefore, kawaiku-aru sounds kind of redundant.

On other hand, kawaiku-nai 可愛くない, "is not cute," isn't redundant, because that's the normal way to negate an i-adjective. In fact, ~ku-nai ~くない is the negative form of i-adjectives.

On the third hand, kawaiku wa aru 可愛くはある, "cute, [it] is," isn't redundant either, simply because the wa は particle is being used to make the sentence contrastive.

Since nai ない can also be analyzed as an adjective, this usage is sometimes classified as a hojo-keiyoushi 補助形容詞, "support adjective," instead. However, this nai ない is without doubt the negative form of aru ある.

Proof of this is that the polite form arimasen ありません can be used instead with the same meaning.

- futsuu de wa arimasen

普通ではありません

Normal, [it] isn't. - kawaiku wa arimasen

可愛くはありません

Cute, [it] isn't.

Lastly: the negative form of verbs has a ~nai ~ない, too, however, that nai ない isn't a support verb, or support adjective. It's a different type of auxiliary called jodoushi 助動詞.

The difference is made obvious by the fact that you can't do with the jodoushi the things you can do with the hojo-doushi.

- wakaranai

分からない

[I] do not understand. - *wakara-aru

分からある

(wrong.) - *wakara wa nai

分からはない

(also wrong.) - *wakara-arimasen

分からありません

(absolutely wrong.)

も Insertion

The mo も particle can also be inserted between the main inflectable and the support expression.This mo も is an inclusive counterpart for wa は. Both of them are classified as kakari-joshi 係助詞, or "binding particles."

- Tarou wa shinda. Jirou mo shinda.

太郎は死んだ。次郎も死んだ

Tarou died. Jirou, too, died.

Since the above works, it makes sense to think it works with support verbs, too:

- tabete wa ita kedo...

食べてはいた・・・

Eating, [he] was, but... - tabete mo ita kedo...

食べてもいたけど・・・

Eating, [he] was also doing, but...

- kirei de mo aru

綺麗でもある

Pretty, [it] also is. - yasuku mo aru

安くもある

Cheap, [it] also is.

An example with negative sentences:

- hanashite wa konai

話してはこない

Talk, [he] doesn't come.- He does other things, but coming talking with me, he does not.

- hanashite mo konai

話してもこない

Talk, [he] doesn't come, also.- Besides not doing other things, he doesn't come talk to me, either.

- He doesn't even come talk to me, besides not doing other things.

Note that ~te-mo ~ても also has another meaning: even if you do something, something else doesn't happen.

- hanashitemo wakaranai

話してもわからない

Even if [I] talk to [him], [he] won't understand.

This happens because the te-form has multiple functions. In particular, it can connect to a support verb, or it can act as a conjunction, connecting to a subsequent clause.

In ~temo wakaranai ~てもわからない, the phrase wakaranai isn't a support verb, so it must be an entire clause, and its ~te ~て must be the conjunction, instead. Unfortunatelly, it's more complicated than that since support verbs have the original, normal verb variants.

- hanashitemo konai

話しても来ない

Even if [I] talk to [him], [he] won't come.- Here, konai 来ない isn't a support verb, but a normal one, heading its own clause.

- This example could mean someone doesn't want to come to a party, for example, and even if you talked to him, you wouldn't be able to convince him to come to the party.

One peculiar thing to note is that the mo も particle can be used as a parallel marker, which sometimes creates a single syntactical subject out of multiple, parallel phrases, and the predicate of that subject is applies to all phrases, in parallel.

- {okane mo shigoto mo} nai

お金も仕事もない

[I] have neither money, nor a job.- This is synonymous with "I don't have money and I don't have a job."

- {banana mo ringo mo} oishii

バナナもリンゴも美味しい

Bananas, and apples, too, are tasty.

Sure enough, this peculiarity applies even to support verbs.

Most commonly, the pattern ~demo~demo nai ~でも~でもない easily translates to "[it] is neither X, nor Y." For example:

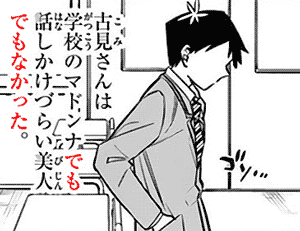

Manga: Komi-san wa, Comyushou desu. 古見さんは、コミュ症です。 (Chapter 5, 喋りたいんです。)

- Context: Tadano 只野 thinks about the school's most popular girl.

- Komi-san wa

gakkou no madonna de mo

hanashi-kake-dzurai bijin

de mo nakatta.

古見さんは学校のマドンナでも話しかけづらい美人でもなかった。

Komi-san was neither the school's madonna

nor a beautiful person [who's] hard to [approach].- hanashi-kakeru

話しかける

To approach and talk with. To start talking to. To begin a conversation with. - Very literally: to pour a conversation onto someone.

- hanashi-kakeru

The same thing can also be done with i-adjectives, using the pattern ~kumo~kumonai ~くも~くもない.

- yasuku mo oishiku mo nai

安くも美味しくもない

[It] is neither cheap nor tasty.

Logically, they can be mixed:

- kirei de mo kawaiku mo nai

綺麗でも可愛くもない

[It] is neither pretty, nor cute.

Of course, it works with other support verbs, too, like iru いる.

- ikite mo shinde mo inai

生きても死んでもいない

[It] is neither alive, nor dead.

And, as one would expect, it doesn't necessarily needs to be a negative sentence.

- mite mo kiite mo iru

見ても聞いてもいる

[I] am seeing, and listening, too.- mite-iru

見ている

To be seeing. - kiite-iru

聞いている

To be hearing. To be listening.

- mite-iru

Other Usages

Technically, hojo-doushi 補助動詞 come after the ren'youkei 連用形 form of verbs and adjectives.It just happens that the te-form is composed by the te て jodoushi 助動詞, which comes from the ren'youkei of the jodoushi tsu つ. Plus, the adverbial form of adjectives is said to be a ren'youkei. And the de で copula is said to be a ren'youkei, too.

They're all ren'youkei, but they aren't all of the ren'youkei. There are other ren'youkei, too.

When i-adjectives come before gozaimasu ございます, they suffer a change in pronunciation called u-onbin ウ音便.

Since gozaimasu is a verb, and adjectives only modify nouns, the adjective is inflected to its adverbial form, its ren'youkei, in order to modify the verb. Therefore, the u-onbin is a ren'youkei, too.

- yoroshii

よろしい

Very well. - yoroshiku gozaimasu

よろしくございます

(same meaning.) - yoroshuu gozaimasu

よろしゅうございます

(same meaning, u-onbin.)

Given this, gozaimasu, just like aru, arimasu, is a hojo-doushi.

Furthermore, gozaimasu has a bunch of variations that also get the same treatment: gozaamasu ござあます, zaamasu ざあます, zamasu ざます, zansu ざんす, and so on.

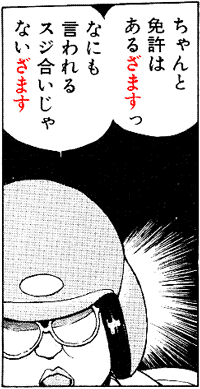

Game: Gyakuten Saiban 2 逆転裁判2

- Kimiko

キミコ

(character name.) - yoroshuu gozaamasu.

よろしゅうござあます。

Very well.

That's fine.

It's alright.

Okay.

These words aren't always used as hojo-doushi, sometimes they're used as jodoushi instead. The only difference is that they don't attach to the ren'youkei, then.

Manga: Taiho Shichau zo 逮捕しちゃうぞ (Chapter 7, 完全無敵の原付おばさん)

- Context: a woman gets stopped by the police.

- chanto menkyo wa aru zamasu'

ちゃんと免許はあるざますっ

[I] properly have a license.

[I] do have a license. - nanimo iwareru zujiai janai zamasu

何も言われるスジ合いじゃないざます

There's no reason for [me] to be said anything.

There's no reason for you to stop me and complain about anything.

Do note that not all verbs that go after a ren'youkei are classified as hojo-doushi, but the hojo-doushi always go after a ren'youkei. For example, the naru なる, "to become," in kawaiku naru 可愛くなる, "to become cute," isn't a hojo-doushi.

Orthography

Like other auxiliaries, the hojo-doushi 補助動詞 are normally spelled with hiragana. That's not to say that they don't have kanji: they do have kanji, but they aren't spelled with kanji.In fact, as a normal verb, they can be spelled with kanji, but as an auxiliary, they normally are not. Observe:

- terebi wo miru

テレビを見る

To see TV.

To watch TV. - terebi wo mite-miru

テレビを見てみる

To try watching TV.

No comments: