For example: nomi-komu 飲み込む, "to gulp down," mochi-dasu 持ち出す, "to take out," bukkorosu ぶっ殺す, "to beat to death," hiki-komoru 引きこもる, "to shut in," and mezameru 目覚める, "to wake up," kawai-sugiru 可愛すぎる, "to be too cute," are all compound verbs.

List

There are way too many compound verbs to list all of them at once. Instead, I'll list some of the common auxiliary verbs found in compound verbs:- ~dasu

~出す

To move something out of somewhere.

To start doing something.- tobi-dasu

飛び出す

To jump out. - omoi-dasu

思い出す

To recall. To remember. (because you're taking memories out of your memory.) - hashiri-dasu

走り出す

To start running.

- tobi-dasu

- ~komu

~込む

To put into a container, to shove into, to cram into.- tobi-komu

飛び込む

To jump in. To dive in. (a hole, for example.) - omoi-komu

思い込む

To assume something to be true. To get in your head that something is true. - fumi-komu

踏み込む

To step into.

- tobi-komu

- ~mawaru

~回る

To go around doing something.- aruki-mawaru

歩き回る

To walk around. (the city, for example.) - sagashi-mawaru

探し回る

To search around. (the city, again.)

- aruki-mawaru

- ~toru

~取る

To take. Used when you acquire something by doing an action.- uke-toru

受け取る

To receive. (a package.) - yomi-toru

読み取る

To read and understand what it's written. (here, "to take" would be like "to get" what it means.) - kiki-torenai

聞き取れない

To not be able to hear-and-take. To not be able to figure out what someone is saying. - sui-toru

吸い取る

To suck out. (e.g. a vampire sucking out blood.) - shibori-toru

搾り取る

To squeeze out. - ne-tori

寝取り

The act of sleeping with someone else's lover.

- uke-toru

- ~nokosu

~残す

To leave remaining.- tabe-nokosu

食べ残す

To eat something partially. To leave leftovers. - nanika ii-nokoshitai koto wa aru ka?

何か言い残したいことはあるか?

Is there something that [you] want to leave said?

Any last words? (before I kill you?)

- tabe-nokosu

- ~kaesu

~返す

To return.- ii-kaesu

言い返す

To say back. - tori-kaesu

取り返す

To take back. - tori-kaeshi no tsukanai koto wo shite-shimatta

取り返しのつかないことをしてしまった

[I] did something that can't be taken back.

[I] did something that can't be undone.

- ii-kaesu

- ~hajimeru

~始める

To start doing something.- yomi-hajimeta

読み始めた

To start reading.

- yomi-hajimeta

- ~kakeru

~掛ける

To start doing something, and be partly doing it, but not finished doing it.

To do something to someone.- ii-kakeru

言い掛ける

To say something, but stop half-way. - shini-kakeru

死にかける

To be about to die. - yobi-kakeru

呼びかける

To call [someone]. (as in: hey! Come here! Oy!!!) - hanashi-kakenaide

話しかけないで

Don't talk [to me].

- ii-kakeru

- ~tsudukeru

~続ける

To keep doing something without stopping, continuously.- benkyou shi-tsudukeru

勉強し続ける

To keep studying. To study continuously. - sakebi-tsudukeru

叫び続ける

To keep screaming. To scream continuously.

- benkyou shi-tsudukeru

- ~owaru

~終わる

To finish doing something.- yomi-owatta

読み終わった

To finish reading.

- yomi-owatta

- ~kiru

~切る

To do something completely.- tabe-kiru

食べ切る

To eat completely. - tsukare-kiru

疲れ切る

To tire completely. To become completely tired.

- tabe-kiru

- ~sugiru

~過ぎる

To do something too much.- tabe-sugiru

食べ過ぎる

To eat too much. - asobi-sugiru

遊び過ぎる

To play too much. - hanashi-sugiru

話し過ぎる

To talk too much.

- tabe-sugiru

- ~naosu

~治す

To do over. To do again, because the first time you did it wrong.- tsukuri-naosu

作り直す

To rebuild. - kangae-naosu

考え直す

To rethink. - ii-naosu

言い直す

To say again, this time properly. To correct oneself.

- tsukuri-naosu

- ~nasai

~なさい

To do. (imperative.)- kotae-nasai

答えなさい

Answer [me].

- kotae-nasai

- bu'~

ぶっ~

To do with force.- buttobasu

ぶっ飛ばす

To hit something so hard you make it fly. To punch someone so hard you know them out of the ground. - bukkakeru

ぶっ掛ける

To pour something so hard it splashes.

- buttobasu

Grammar

The term fukugou-doushi 複合動詞 refers to literally any word that's a compound, that's composed of multiple words, and which is a verb, because the head of the compound is a verb.Incidentally, if the head was an adjective, the term would be fukugou-keiyoushi 複合形容詞, "compound adjective," instead.

A consequence of this simplistic definition is that not all compound verbs are the same. In particular, they differ according to their stem: some compound verbs have a verb for stem, others have nouns, adjectives, or even adverbs.(張威, 2009:126)

- oi-tsuku

追いつく

To chase and attach to. (literally.)

To catch up with.- Verb plus verb.

- kizu-tsuku

傷つく

To injury-attach to. (literally.)

To get injured.- Noun plus verb.

- chika-yoru

近寄る

To approach.- Adjective plus verb.

- bura-sagaru

ぶら下がる

To dangle.- Adverb plus verb.

Despite this plurality of compound verb types, an overwhelming majority of them—really, around 90%—are verb plus verb.(張威, 2009:128)

Pronunciation

Like any other suffix, the suffixed verb of compound verbs can be affected by changes in pronunciation. For example:- kiru

着る

To wear. - kaeru

替える

To replace. - ki-gaeru

着替える

To change clothes.- Here, ki き changed to gi ぎ due to rendaku 連濁.

- kaku

掻く

To scratch. - harau

払う

To pay.

To wipe away. - kapparau

掻っ払う

To steal. To snatch.- Here, kaki-ha かきは became kappa かっぱ due to sokuonbin 促音便.

Verb + Verb

In compound verbs formed by a verb stem and a verb suffix, the stem is conjugated its ren'youkei 連用形 noun form. For example:- kaku

書く

To write. - kaki

書き

Writing. Written. - kaki-nokosu

書き残す

To leave [something] written [somewhere].

- tsuki-au

付き合う

To hang with. To do an activity with.

To date with. - kuri-kaesu

繰り返す

To repeat. To do the same thing again.

Note that this form ends in ~i for godan verbs, but for ichidan verbs the ~ru is removed instead.

- kiru

切る

To cut.- A godan verb.

- kiri-komu

切り込む

To cut deep into. (the blade gets shoved deep into the target.)

- kiru

着る

To wear.- An ichidan verb.

- ki-komu

着込む

To wear extra clothes. (you get shoved inside extra layers of clothing.)

The stem verb in a compound verb must be in noun form, which is a ren'youkei 連用形 form. However, that doesn't mean it must be the ren'youkei of its plain form. It's possible to conjugate the stem verb to passive or causative, before affixing the suffix verb:

- tabe-tsudukeru

食べ続ける

To keep eating. - taberare-tsudukeru

食べられ続ける

To keep being eaten. - tabesase-tsudukeru

食べさせ続ける

To keep forcing [someone] to eat [something]. - tabesaserare-tsudukeru

食べさせられ続ける

To keep being forced to eat [something] by [someone].

The head verb can be conjugated, too.

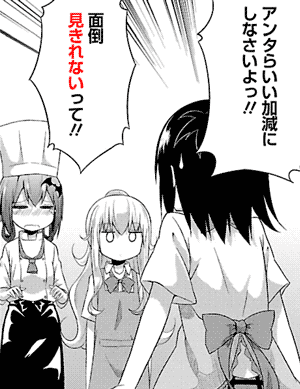

Manga: Gabriel DropOut, ガヴリールドロップアウト (Chapter 5)

- Context: Vignette learns the harsh realities of doing group projects.

- anta-ra ii-kagen ni shinasai yo'!!

アンタらいい加減にしなさいよっ!!

You [two], stop it already!! - mendou mi-kirenai tte!!

面倒見きれないって!!

I can't take care of all the trouble you make!!- mendou

面倒

Trouble. - mendou wo miru

面倒を見る

To see trouble.

To take care of trouble.

To take care of someone, which is trouble, in the sense of it may cause trouble to you to do it. - mendou wo mi-kiru

面倒を見きる

To completely take care. - mendou wo mi-kireru

面倒を見きれる

To be able to completely take care.

(potential form.) - mendou wo mi-kirenai

面倒を見きれない

To not be able to completely take care.

(negative potential form.) - Vignette can't handle all this trouble.

- mendou

Some verbs, due to changes in pronunciation, end up not really being in the ren'youkei form.

- oi-kakaeru

追いかける

To chase someone. - okkakeru

追っかける

(same meaning.)

Deep Compounds

Syntactically, a compound verb is a verb. And a compound verb can be composed of two verbs. That means you can compose a compound verb out of a compound verb and another verb.- hiki-ageru

引き上げる

To pull up. - hiki-age-nobasu

引き上げ伸ばす

To stretch by pulling up. - hiki-age-nobashi-tsudukeru

引き上げ伸ばし続ける

To keep stretching by pulling up.

Neology

In general, compound verbs are well-established words that you can find in dictionaries. That is, you don't normally just grab a random verb and attach it to another verb to make a compound.That said, it's totally possible to take an auxiliary verb and attach it to a random word. For example, the auxiliary verb ~hajimeru ~始める pretty obviously means "to start doing something," no matter what you attach it on.

- guguru

ググる

To google. To search on google. (a neologism.) - iroiro guguri-hajimeta

色々ググり始めた

To have started googling various things.

Semantic Bleaching

Some verbs are said to become semantically bleached when they're used as the auxiliary verb of a compound verb. That is, their meaning as an auxiliary is completely different from their meaning as a normal verb.For example, kiru 切る means "to cut." It has nothing to do with ~kiru ~切る, "to do completely."

Except that kiri ga nai 切りがない means "having no end," "going on forever," "impossible to finish no mater how long you keep doing it," and so on.

Therefore, I'm not really such they've lost their original meanings when used as auxiliaries, or they just had multiple meanings to begin with.

Polysemy

Some verbs have multiple meanings, and, consequently, when they're used in compound verbs, the compound verb ends up having multiple meanings, too.For example, oriru 降りる means "to fall," but it can also mean "to get out of a vehicle." Consequently, tobi-oriru 飛び降りる can mean either "to jump from a high place and fall," or "to jump out of a vehicle."

Auxiliary Verb

The auxiliary verb of a compound verb is often, but not always, the suffix verb. Consequently, the main verb is often, but not always, the stem verb.Basically, the main verb is the verb that expresses the main action of the compound. Observe:

- uchi-kaesu

撃ち返す

To shoot back. - uchi-korosu

撃ち殺す

To kill by shooting.

In the first example, the main verb is the stem, but in the second verb, the main verb is the suffix, and the stem is an auxiliary.

This happens because there are three different classes of auxiliary verbs:(Niimi et al., 1987, as cited in Uchiyama et al., 2005:6)

- The aspectual class.

Whether the action has begun, finished, is continuing, and so on.

For example, ~hajimeru ~始める. - The spatial class.

Toward what direction the action is going.

For example, ~ageru ~上げる. - The adverbial class.

How the action is performed.

For example, ~sugiru ~過ぎる.

Among the classes above, aspect and space are easily distinguishable. The verbs to start, to finish, etc. are aspect. The verbs to rise, to drop, to take out, to put in, etc. are spatial.

The problem is the adverbial class.

In general, if a verb has been semantically bleached, it's used as an adverbial auxiliary. For example, mawaru 回る originally means "to turn around," "to roll." Going "around" is a more adverbial usage of it.

Sometimes, compound verbs are composed of a stem that describes the process, and a suffix that describes the change or outcome of the process. In such cases, the verb describing the process is working adverbially, and therefore is the auxiliary.

Observe the examples below:

- hiku

引く

To pull. - hiki-dasu

引き出す

To pull out. - hiki-ageru

引き上げる

To pull up. - hiki-nobasu

引き伸ばす

To stretch by pulling. - hiki-saku

引き裂く

To tear apart by pulling.

The stem verb is hiku 引く in all examples, but in the last two examples, hiku 引く works adverbially, and the main verb is the suffix instead.

In such cases, it's possible to replace the stem verb by its te-form.

- hiite nobasu

引いて伸ばす

To pull [it], subsequently stretching [it]. - hiite saku

引いて裂く

To pull [it], subsequently tearing [it].

This is even more obvious in verbs like this:

- tsukatte suteru

使って捨てる

To use and to throw away. - tsukai-suteru

使い捨てる

To throw something away after using it.

Note that this principle governs the correct order of the verbs in a compound. Observe:

- uchi-korosu

撃ち殺す

To shoot someone, then killing them.

To kill someone by shooting them. - koroshi-utsu

殺し撃つ

To kill someone, then shooting them.

To shoot someone by killing them.- This doesn't make any sense.

- It literally means you kill somebody first, and then you shoot their corpse. Why would you do that? What's the point of such savagery?

The spatial class of auxiliaries works the same way logically, but ends up being classified the opposite way.

For example, the verb ageru 上げる means "to raise" something. Therefore, we can interpret hiki-ageru 引き上げる as "to raise something by pulling it," which would make hiki the auxiliary.

Similarly, hiki-sageru 引き下げる, "to lower something by pulling it," or "to pull something down."

So which one is it? Is the verb hiku the auxiliary, or is it sageru?

In such cases, ageru 上げる and sageru 下げる are the auxiliaries. This happens because the spatial auxiliaries may appear to be verbs expressing an actual action of moving things, but, upon closer inspection, they're only there to describe what's the final direction of the action.

We know this because spatial auxiliaries can be suffixed to verbs that don't mean physical actions. For example:

- naru

成る

To become. - nari-agaru

成り上がる

To become something greater. To rise in rank.- For example, to become rich, to become a company president, to become a king, and so on.

- nari-sagaru

成り下がる

To become something lesser. To drop in rank.- This is a way more common word in anime than nari-agaru. Basically every time you have a character who's a noble, or king, or anyone in a high social position, who ends up losing such status because of whatever shenanigans, this word applies.

- For example, a teacher ending up becoming a student's summoned beast. A princess ended up becoming a maid. One of the demon lord's generals being reduced to a NEET who does nothing but eat and play games on the internet every day.

None of the compound verbs above can be interpreted as "to raise or lower by becoming," agaru 上がる and sagaru 下がる are auxiliaries that merely describe the direction, they don't actually mean the action of moving something.

By the way, there are terms to classify auxiliary verbs according to their position.[複合動詞の成立条件 - osaka-kyoiku.ac.jp/~kokugo, accessed in 2019-07-17]

- zenkou-doushi

前項動詞

The auxiliary comes before the main verb. - koukou-doushi

後項動詞

The auxiliary comes after the main verb. - ryoukou-doushi

両項動詞

The auxiliary can come either before or after the main verb.

Transitivity

Compound verbs are affected by the transitivity of the verbal head. In particular, some verbs feature ergative verb pairs, and which verb is used depends on the transitivity of the stem verb.For example deru 出る, "to go out," has the lexical causative counterpart dasu 出す, "to put out."

- tsuku

突く

To thrust. - shita wo tsuki-dasu

舌を突き出す

To stick out [your] tongue. - atama kara tsuno ga tsuki-deru

頭から角が突き出る

Horns stick out from [his] head.

Above, the ergative verb pair deru and dasu form an ergative verb pair of compound verbs: tsuki-deru and tsuki-dasu. The verb tsuki-deru is intransitive, so what "sticks out" is marked as the subject, while tsuki-dasu is transitive, so what "is caused to stick out" is marked as the object.

Unfortunately, it's more complicated than that.

For example, dasu 出す as an auxiliary verb can also mean "to start doing [something]." Consequently, sometimes a compound verb has a deru and a dasu variant, but they don't form an ergative pair. Observe:

- mizu ga nagare-deru

水が流れ出る

Water flows out. - mizu ga nagare-dasu

水が流れ出す

Water begins to flow.

The reason it doesn't work as you'd expect is because nagareru 流れる, "to flow," is intransitive and forms an ergative verb pair with nagasu 流す, "to make flow," "to flush." Consequently, the correct transitive combination would be this:

- mizu wo nagashi-dasu

水を流し出す

To flush out water.

Some verbs aren't part of ergative pairs. For example, the verb kiru 切る, "to cut," is transitive, and has no intransitive counterpart.

- kiri-otosu

切り落とす

To cut [something] off, causing it to fall, because of gravity.

The verb otosu 落とす, "to cause to fall," "to drop," forms an ergative verb pair with the intransitive verb ochiru 落ちる, "to fall." Since kiru 切る is transitive, we can use otosu 落とす with it, but not ochiru 落ちる.

- *kiri-ochiru

切り落ちる

(you can't say this, because kiru is transitive, while ochiru is intransitive.)

It's technically possible to attach ochiru to kiru in its passive form:

- kirare-ochiru

切られ落ちる

To be cut, and then fall.

However, it's more normal to just use the passive form of the compound verb instead:

- kiri-otosareru

切り落とされる

To be cut and dropped.

A common ergative pair to watch out for is agaru 上がる, "to rise," and ageru 上げる, "to raise."

- yuusha wa mou ichido tachi-agaru

勇者はもう一度立ち上がる

The hero shall stand up one more time. - iwa wo mochi-ageru

岩を持ち上げる

To grab-up a boulder.

To lift a boulder.

English has more ergative verbs than ergative verb pairs, consequently, you can end up with an intransitive compound verb and a transitive compound verb that translate to literally the same thing in English. For example:

- yaku

焼く

To burn [something]. (transitive.) - yaki-korosu

焼き殺す

To kill by burning.

To burn to death. (transitive.) - yakeru

焼ける

To burn. (intransitive.) - yake-shinu

焼け死ぬ

To die by burning.

To burn to death. (intransitive.)

Noun + Verb

Some compound verbs are composed of a noun plus a verb instead.- tabi-datsu

旅立つ

To go on a journey. - se-ou

背負う

To bear. (a responsibility.) - te-watasu

手渡す

To hand over. To surrender.

In some cases, it's possible to start with a properly marked sentence, then replace the particles with nothing (see: null particle), and then turn that into a compound verb. For example:

- na wo tsukeru

名をつける

To attach a name.

To name. - na-dzukeru

名付ける

To name [someone]. To give a name. (like to a pet.)

However, most of the time this doesn't really work. For example:

- na-noru

名乗る

To name [oneself]. To state your own name. To claim to be a certain person. - na wo noru

名を乗る

To embark a name. (literally.)

To take over a name. To claim a name. To claim to be a certain person.

Although the above should mean the same thing, the properly marked phrase isn't really used, only the compound verb na-noru is used.

Adjective Plus Noun

Sometimes, the stem of a compound verb is an i-adjective. When this happens, the steam of the i-adjective is used, that is, without the ~i ~い suffix.- chikai

近い

Near. - chika-dzuku

近づく

To approach.

- nagai

長い

Long. - naga-biku

長引く

To be prolonged.

There are few compound verbs that follow this pattern. Most of the time, it's going to be the verb sugiru 過ぎる that will be attached to the adjective.

- oo-sugiru

多すぎる

Too many. - taka-sugiru

高すぎる

Too high.

Too expensive. - tsuyo-sugiru

強すぎる

Too strong.

Adverb Plus Verb

In extremely few cases, the stem of the compound verb is an adverb.- bura-sageru

ぶら下げる

To dangle. - bata-tsuku

バタつく

To move around without calming down.

Both the adverbs above happen to be mimetic words, and can be reduplicated: burabura ぶらぶら, *dangling,* *swaying to and from,* batabata バタバタ, *flapping.*

Nominalization

There are many words made out of conjugating compound verbs to their noun forms.For example, some names of foods are nominalized compound verbs with the head yaku 焼く, "to heat," "to burn," "to roast," "to grill," "to bake," etc.

- okonomi-yaki

お好み焼き

A pancake with various ingredients.- okonomi

お好み

Your preference. Your liking. - o お

Honorific prefix. - konomu

好む

To like something. To prefer something.

- okonomi

- tamago-yaki

卵焼き

A rolled omelet.- tamago

卵

Egg.

- tamago

- suki-yaki

すき焼き

A dish with thinly sliced pieces of meat.- suki

鋤

Spade. - Origin: in the past, farmers used to use the spade of farming tools as a cooking utensil, hence the name.[すき焼き - iroha-japan.net, accessed 2019-10-30.]

- suki

- medama-yaki

目玉焼き

Fried egg, sunny side up.- medama

目玉

Eyeball.

The yolk of a fried egg. (from its shape.)

- medama

- tai-yaki

たいやき

A fish-shaped pancake.

It's also seen in names of games, like:

- ishi-keri

石蹴り

Stone-kicking.

A game like hopscotch, but you kick the stone instead of throwing it with your hand. - shiri-tori

尻取り

Butt-taking.

A word game where someone says a word, and the next person has to say a word that starts with the same kana 仮名 as the previous word ends with. Repeating words or saying a word that ends in n ん makes you lose.- shi-ri-to-ri

しりとり

(game start.) - ringo

林檎

Apple. - gohan

ご飯

Food. Meal. Rice.

(game ends.)

- shi-ri-to-ri

Other Suffixes

There are some suffixes that look like they form fukugou-doushi 複合動詞, "compound verbs," but in reality they don't.- kaki-yasui

書きやすい

Easy to write.- Here, yasui forms a compound adjective, fukugou-keiyoushi 複合形容詞, instead.

- kaki-tai

書きたい

[I] want to write.- Here, ~tai ~たい is a jodoushi 助動詞 instead because ~tai doesn't mean anything on its own..

- kaki-yagaru

書きやがる

[He] has the nerve to write [it].- Here, ~yagaru ~やがる is a jodoushi 助動詞, too, because it doesn't mean anything on its own, even though its origin would be the verb agaru 上がる..

- kaite-ageru

書いてあげる

[I] will write [it] for [you].- Here, ~ageru ~あげる is a hojo-doushi 補助動詞, "support verb," instead, because it goes after the te-form of the verb kaku 書く, which is kaite 書いて, not the noun form, kaki 書き.

No comments: