Synonymous variants include datte だって, with the tte って particle instead, desu to ですと, with the desu です polite copula instead, and desu tte ですって.

Grammar

For the most part, dato だと works just like the sum of its parts: to と introduces a sentence as object for a verb like "to say," iu 言う, and when da だ happens to be at the end of that sentence, you get dato だと.- Tarou wa "shiranai" to itta

太郎は「知らない」と言った

Tarou said "[I] don't know." - Tarou wa "kirei da" to itta

太郎は「綺麗だ」と言った

Tarou said "[it] is pretty."

Above we can see them neatly divided because of the quotation marks. Usually, however, they show up like this:

Manga: Kaguya-sama wa Kokurasetai ~Tensai-Tachi no Ren'ai Zunousen かぐや様は告らせたい~天才たちの恋愛頭脳戦~ (Chapter 1, 映画に誘わせたい)

- mattaku

全く

[Good grief.] - gesewa na gumin-domo

全く下世話な愚民共

[What a lot of prattling fools.]- gesewa na 下世話な

[Someone] who chit-chats, prattles. - gumin 愚民

Foolish people.

- gesewa na 下世話な

- kono watashi wo dare da to omotteru no?

この私を誰だと思ってるの?

Who do [they] think I am?

As you'd expect, the same thing applies to derived constructions. Some examples:

- Kurisumasu da to iu no ni

クリスマスだというのに

Even though [it] is Christmas. - sou da to shitara

そうだとしたら

If [it] were so.

If that were the case. - sou da to shitemo

そうだとしても

Even if [it] were so.

Even if that were the case.

- nan-da to?!

なんだと?!

What did [you] say?! - nan-desu to?!

なんですと?!

(same meaning.) - nan-da tte?!

なんだって?!

(same meaning.) - nan-desu tte?!

なんですって?!

(same meaning.)

ないだと

Sometimes, dato だと can up in places where da だ alone would be ungrammatical. This specially happens when dato だと is at the end of the sentence, in which case it kind of works like "you say," as in: to shreds, you say? Observe:- yasui

安い

[It] is cheap. - *yasui da

安いだ

(wrong.)- You can't use da だ directly after an i-adjective.

- yasui da to?!

安いだと?!

[It] is cheap, [you say]?!

- nigeru

逃げる

To run away. To escape. To fly. - *nigeru da

逃げるだ

(wrong.)- You can't use da だ directly after a verb.

- nigeru da to?!

逃げるだと?!

Run away, [you say]?!

Note that, although you can't say either of the above, you can say yasui-n-da 安いんだ, nigeru no da 逃げるのだ, and so on. These work because the no の nominalizer, or its contraction, n ん, acts as a noun before da だ, and da だ can come right after nouns.

What's happening in the dato だと sentences above is different.

Basically, the explanation for the above is that the da だ copula features some metalinguistic functions.(三枝令子, 2000)

To elaborate: da だ isn't inside the phrase preceding it, but outside of it. Since it's not inside of the phrase, it's not bound by the syntax within the phrase.

- "yasui" da to?!

「安い」だと?!

"[It] is cheap," [you say]?!

Since "__" da to 「〇〇」だと looks exactly like "___ da" to 「〇〇だ」と most of the time, people learning Japanese end up thinking they're the same thing, when they're actually different things, that only happen to look like literally the same thing.

Because Japanese hates you.

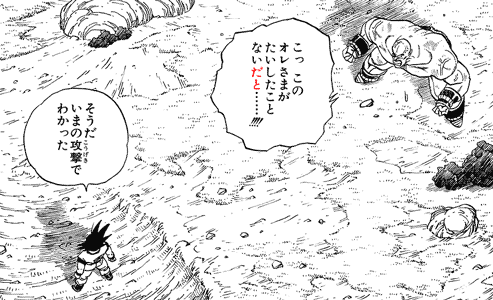

Manga: Dragon Ball, ドラゴンボール (Chapter 225, ナッパ ても足も出ず)

- ko' kono

ore-sama ga

taishita koto

nai dato......!!!!

こっ このオレさまがたいしたことないだと・・・・・・!!!!

Th-- this me isn't [a big deal], [you say]......!!!!- Here, nai da ないだ would be ungrammatical if not metalinguitic.

- sou da

そうだ

[That's right.] - ima no kougeki de

wakatta

いまの攻撃で わかった

With [that] attack [just] now [I] realized.

(Goku figured Nappa isn't a big deal from how weak his attack was.)

だだと

Of course, since we have one da だ as metalanguage and one da だ as object language, there's nothing stopping us from having both of them at the same time like some sort of mad man. Behold:- dare da, da to?!

誰だ、だと?!

Who is [it], [you say]?!- Don't you know who I am?!

Yep. This is grammatically correct.

You have no reason to ever say it in your life, and for the love of all that's holy please don't, but it's technically grammatically correct.

Can you elaborate on using を in

ReplyDeleteこの私を誰だと思ってるの?

The verb 思う takes a を-marked an a と-marked argument. What's marked by と is what the subject thinks. What's marked by を it's about what they think it.

DeleteIn the sentence, what the subject thinks about この私 is 誰だ. This 誰だ doesn't mean "is who," it means an indefinite "who," because だ can be used with indefinite pronouns like this. e.g. お前は誰だ = "who are you," and not "you is who."

これをなんだと思ってるの? = "what do you think this is?"

戦争を悪いと思う = to think "bad" about "war." To think that war is bad.