In Japanese, ~dano~dano ~だの~だの is normally used to list examples of things that the speaker is complaining about.

Not to be confused with the no-adjective tada no ただの, "just," "merely." Or with a verb in past form plus the no の particle: yonda no? 読んだの?, "did you read it?"

Grammar

The word dano だの is a parallel marker like the to と particle. However, while to と easily translates to English as simply "and," the meaning of dano だの can't be as easily conveyed.

Most of the time, dano だの lists examples of "worthless things" or "unrealistic things." (鈴木智美, 2004:11)

In other words, dano だの lists nonsense, absurdness, foolishness, and other stuff in a dismissive tone. It's normally used when the speaker is somehow perplexed about such things, or is making a remark or complaint that includes such things as examples of what he's talking about.

However, dictionaries don't go as far as saying that dano だの is used exclusively in this way. Indeed, it seems that most of the time it's used to list things that someone said, or did, that you're complaining about, but I'm not really sure if it's always used this way.

Examples

For reference, some examples.

- {shougakusei no} musuko ni {keitai dano pasokon dano} to urusaku segamarete komatta

小学生の息子に携帯だのパソコンだのとうるさくせがまれて困った

[I'm] troubled [because] [my] son [who] {is a grade school student} keeps pestering [me] about {cellphones and computers}.- Here, the speaker is probably complaining that his son wants a cellphone or a computer, and keeps pestering him about it. Given his son is still in grade school, he probably doesn't want to buy him those things.

- Note that the to と particle is acting as a quoting particle for the things that the son literally said.

- Source: 鈴木智美, 2004.

- {mazui dano kirai dano} to otto wa ryouri ni monku bakari itte-iru

まずいだのきらいだのと夫は料理に文句ばかり言っている

{[It's] bad, [I] hate [it]}, [my] husband keeps complaining about [my] cooking.- Here, the speaker is complaining that her husband is complaining about her cooking.

- Source: 鈴木智美, 2004.

Note that worthlessness or lack of realism is relative. For example:

- {{nagame ga subarashii dano tsukuri ga goojasu dano} to iu} senden-monku de, toshin no koukyuu manshon ga {{tobu} you ni} urete-iru rashii

眺めがすばらしいだのつくりがゴージャスだのという宣伝文句で、都心の高級マンションが飛ぶように売れているらしい

[I heard that]: with a sales message [that] {says {the view is amazing, the construction is gorgeous}}, the high-grade houses in the city center are being sold {like {[they're] flying away}}.- Here, the points listed, the view being amazing, the construction being gorgeous, sound pretty good, however, they're considered to be worthless by the speaker, given that the speaker is using dano だの.

- This happens because the speaker is talking about high-grade, koukyuu 高級, homes. In other words: the speaker is poor, and can't relate with choosing a house based on how good the view is or how it's constructed.

- Source: 鈴木智美, 2004.

- {kinu dano houseki dano}, {{toshi-goro no} oujo ga yorokobi-sou na} okurimono wo yama-hodo sasage-motsu

絹だの宝石だの、年頃の王女が喜びそうな贈り物を山ほど捧げ持つ

{Silk, jewels}, [they] held up a mountain of gifts [that] {were likely to please a princess {of marriage-age}}.- toshi-goro

年頃

Around-age. Generally refers to a girl who's about old enough to marry. - sasage-motsu

捧げ持つ

To lift-up and hold. In particular, when making offerings to some important entity, like a princess, to hold something up with both your hands to present it to them. - Source: 本当は恐ろしいグリム童話, via BCCWJ.

- toshi-goro

- {ai dano heiwa dano jiyuu dano} to, tetsugaku-ppoku ronri-teki ni yuujin-tachi to katari-au, sonna {komasshakureta ao-kusai} jidai demo atte

愛だの平和だの自由だのと、哲学っぽく論理的に友人達と語り合う、そんなこまっしゃくれた青臭い時代でも在って

{Love, peace, freedom}, talking with [my] friends logically in a philosophical manner, such {cheeky, immature} age existed [for me], and (rest omitted.)- Here, the speaker is talking about a time when they were younger, and talked with their friends about grandiose (i.e. unrealistic) ideals, like love, peace, and freedom. As opposed to realistic topics, like gas prices, and the inflation.

- Source: a Yahoo! blog, via BCCWJ.

Like other parallel markers, one element marked by dano だの can be a verb whose arguments are recoverable from a separate element. Observe:

- ima doki otoko no ko unda kara tte {namae tsugu dano tsuganai dano}, kankei nai desu yo

いまどき男の子産んだからって名前継ぐだの継がないだの、関係ないですよ

These days because [you] gave birth to a boy {[he] will inherit your name, won't [inherit your name]}, that has nothing to do with [it].- This sentence says that just because your child is boy, as opposed to a girl, he won't necessarily inherit your name, or that a girl wouldn't be able to inherit it.

- In Japan, traditionally businesses were associated to the families that ran those businesses, and the name of the family was the name of the business.

- For example: Honda Soichirou 本田宗一郎 is the founder of Honda Motors.

- Normally, in order to inherit the family name, you'd have to be male, since the married name of a woman would become the husband's name. Furthermore, it was normally the first, and oldest son that inherited it. Note: ichirou 一郎 means "first son." One exception were richer families that only had daughters: then there was a motivation for the husband to change his names instead, a practice called muko-youshi 婿養子, "adopted son-in-law."

- Japanese culture aside, in the sentence above tsuganai 継がない, "doesn't inherit (what?)," is a verb whose object can be found in the previous dano だの: namae wo tsugu, "inherit the name."

- Source: Yahoo! Chiebukuro, via BCCWJ.

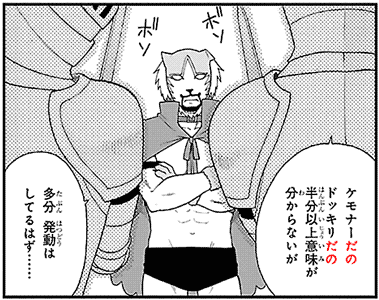

- Context: a modern-world professional wrestler is summoned to a fantasy medieval isekai 異世界 as a powerful hero. He introduces himself as a furry and mistakes the whole thing as a hidden-camera prank. The soldiers, having no idea what he's talking about, begin to wonder whether the spell that translates what the summoned hero says is working as intended.

- kemonaa dano

dokkiri dano

hanbun ijou imi ga

wakaranai ga

ケモナーだのドッキリだの半分以上意味が分からないが

Furry, hidden-camera prank, [I] don't get more than half [of what he's saying], but.- imi ga wakaranai

意味が分からない

[I] don't understand the meaning.

[I] don't get [it].

- imi ga wakaranai

- tabun, hatsudou wa

shiteru hazu......

多分 発動はしてるはず・・・・・・

Probably, functioning it is.- Contrastive wa は - the translation magic, functioning, it is, but his words being understandable, it isn't.

- hazu はず

A formal noun used when you expect, or suppose, that something is true. In this case, the soldier supposes the translation magic should be functioning.

vs. ~といい~といい

A construction similar to ~dano~dano is ~to ii ~to ii ~といい~といい. However, there's a difference between them.

The construction ~dano~dano is used when you're talking about the elements listed, while the construction ~to-ii~to-ii is used when you're making a conclusion based on the elements listed.

- Edogaa-san

koitsu

atashi no souzou ijou ni

yabai yatsu desu!!

エドガーさんこいつあたしの想像以上にヤバイヤツです!!

Edgar-san, this [guy] is more dangerous than I imagined!- atashi no souzou ijou ni

あたしの想像以上に

Above my imagination.

- atashi no souzou ijou ni

- kakkou to ii

gendou to ii

koitsu wa kikaku-gai no

hentai da......!!

格好といい言動といいこいつは規格外の変態だ・・・・・・!!

(Citing) [his] appearance, the things [he] said and did, (conclusion) this guy is an unparalleled pervert......!!- Given how he looks, and what he says and does, this guy is way worse than the average pervert......!!

- kakkou

格好

Appearance. Looks. Outfit. - gendou

言動

What one says and does. In other words: - kotoba to koudou

言葉と行動

Words and actions. - kikaku-gai

規格外

Outside of the standard. Like no other. Without compare. Unparalleled.

~だの~など

Sometimes, dano だの can be followed by nado など, "et cetera," instead of another dano だの. For example:

- reizouko ni {pengin dano, hakuchou dano, ookina sakana nado} takusan no kenkyuu zairyou ga hokan sarete-iru

冷凍庫にペンギンだの、白鳥だの、大きな魚など沢山の研究材料が保管されている

In the freezer a lot of research material is being stored: {penguins, swans, large fishes, and so on}.- Source: a Yahoo! blog, via BCCWJ.

- kono ittai mo {yatai dano ippai-nomi-ya nado} ga tachi-narabimashita

この一帯も屋台だの一杯飲み屋などが建ち並びました

In this area, too, {market stalls, bars, etc.} were built side-by-side.- ippai

一杯

One glass. (of alcohol, for example.) - Source: 東京裏路地〈懐〉食紀行, via BCCWJ.

- ippai

Etymology

Morphologically, dano だの originates from the da だ copula and the no の particle.[だの - 大辞林 第三版 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2019-10-04]

However, unlike the da だ copula, dano だの can come right after an i-adjective, which means it doesn't work like the parts that compose it after all.

- atsui dano, samui dano

暑いだの寒いだの

[It] is hot, [it] is cold. (someone keeps complaining about the temperature!)

To complicate matters further, although dano だの is a parallel marker, the would-be polite variant desu no ですの is not.

The phrase desu no ですの is only valid because the no の nominalizer can exceptionally be qualified by polite forms. Normally, nouns can only be qualified by the na な attributive copula, not by the polite copula desu です.

Even furtherly complicated, the plain variant of desu no ですの isn't da no だの either, it's na no なの. At very least, in modern Japanese it's na no なの.

- sore da no ni

それだのに

(...an old way of saying...)- sore na no ni

それなのに

Even though that.

Even though [I did that]. Even though [that happened]. Even though [that is true]. - According to: それだのに - 大辞林 第三版 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2019-10-15.

- sore na no ni

On the plus side, this means dano だの pretty much always means the parallel marker described in this article, not anything else.

This is a bit off-topic, but I've been reading your articles for some time now so I figured you would be a good person to ask. Why do Japanese people sometimes pronounce Rs as Ls?(Not talking about when they speak English) I think I've only heard this in music but I might be wrong. I was thinking it might just be because Japanese people find it difficult to extend the R sound and so they just turn it into an L sound. Do you know anything about why that might be?

ReplyDeleteYou may want to read this

Delete