Manga: Machikado Mazoku まちカドまぞく (Volume 1, Page 113, 普通に加熱することの難しさ)

Echoic Topic

The most basic usage of tte って as a topic is when it literally quotes a word or phrase used by another interlocutor. For example:- yabai yo! Karamatsu ga yuukai sarechatta!

やばいよ!カラ松が誘拐されちゃった!

It's terrible! Karamatsu was kidnapped! - Karamatsu tte dare?

カラ松って誰?

Who is Karamatsu? - —Anime: Osomatsu-san おそ松さん, Episode 5.

Above, the topicalized Karamatsu is marked by tte って because the previous interlocutor literally said the word Karamatsu.

This kind of quotative topic is different from the usual wa は topic. The key difference is that it topicalizes the phrase literally, it topicalizes what was said, written, uttered, and so on, as opposed to the underlying meaning of the word.

Observe the difference below:

- dare tte, hidoi!

誰って、酷い!

Saying "who" is horrible! (Karamatsu is your brother!) - *dare wa hidoi!

誰は酷い!

(invalid.)

Semantically, interrogative pronouns can't be the topic, they must be focus, therefore they can't be marked by wa は.

However, the interrogative pronoun as a literal word ("dare") can be topicalized by tte って, in which case the sentence comments on the fact the word was said, on the utterance of the word, rather than on the underlying meaning of the pronoun.

Similarly:

- anata wa shitsurei

あなたは失礼

You are impolite. - anata tte shitsurei

あなたって失礼

"You" is impolite.- In Japanese, you generally refer to people by their names, not by second person pronouns like anata, ergo, saying "anata" is impolite under certain circumstances.

Normally, we use words to talk about things, but with the echoic marker, we're using words to talk about words, which were used to talk about things, in other words: we're using language to talk about language. In linguistics, the term metalanguage refers to this phenomenon.

Manga: Machikado Mazoku まちカドまぞく (Volume 1, Page 113, 普通に加熱することの難しさ)

- Context: Momo can't cook like a normal person. She's impressed by Shamiko's normal cooking skills.

- ...sou da ne, Shamiko futsuu ni Win'naa itameteta mon ne

・・・そうだねシャミ子普通にウィンナー炒めてたもんね

That's right, Shimiko can fry wieners normally. - ryouri wa dekiru-n-da ne

料理はできるもんだね

Cooking, [you] can do, huh.

- "wa" tte nan-desu ka!!

「は」ってなんですか!!

What do you mean by "wa"??!!- In a double subject construction containing a potential, like "can do," the small subject is normally marked by the ga が particle.

- Shamiko wa ryouri ga dekiru

シャミ子は料理ができる

{Do-able is true about cooking} is true about Shamiko.

Shamiko can cook. - Marking ryouri with wa は instead making it a contrastive wa は, in this case, with the following implicature:

- Cooking, Shamiko can do. Implicature: Shamiko can't do anything else. She's a klutz.

In the example above, the topic marker wa は was marked as the echoic topic by tte って due to the speaker's (Shamiko's) vexation for the contrastive implicature that the only thing she can do right is cooking, and she can't do anything else right.

As one might guess, it's absolutely impossible to translate this literally to English. The function of wa は in this case would probably happen in English by stressing "cooking" instead: oh, COOKING you can do. What do you mean by "COOKING"?!! Why are you saying that word that way?!

Combined with a pronoun like sore それ, "that," the topic marker tte って can refer to what an interlocutor is saying, or trying to say.(Maynard, 2002, as cited in Suzuki, 2006:72)

- otoko ni moteta?

男にモテた?

Were you popular with guys? - un? sore tte shinpai shite-kurete-n-no?

うん?それって心配してくれてんの?

Um? Is "that" [you] worrying about [me]?

The tte って particle is generally used when you have something new or different to say about a topic. It isn't used if all you're doing is confirming what somebody else already said. For example:(Niwa, 1994, as cited in Suzuki, 2006:76)

- Tarou wa masutaa no ninen-me datta kke?

太郎はマスターの2年目だったっけ?

Was Tarou at [his] second year of [his] Master's? - ee, sou desu. Tarou (wa/?tte) shuushi no nikaisei desu

ええ、そうです。太郎(は/って)修士の2回生です

Yes, that' right. Tarou is a second year student of the Master's program.

In the second sentence above, the wa は particle is used to mark the topic. You don't use tte って because the speaker is merely confirming something already said by another interlocutor.

In a more general sense, the nature of this tte って is interjectory: you interject on what someone said to exclaim a doubt about it or an opinion about it. Since confirming questions doesn't constitute of an interjection, tte って isn't used.

Familiar Topic

The tte って topic marker can also be used in questions about things that are more familiar to the answerer than to the questioner.This function is similar to the echoic topic. With the echoic topic, it's often the case that someone says something, and someone else asks what the word means. Clearly, the person that used the word first is more familiar with that word than the person who asked about it.

- Q: Do you like cats?

- A: What is a "cat"?

- Above, Q is clearly more familiar with cats than A is, after all, Q knows the word "cat," while A does not.

Similarly, the tte って particle can mark a topic that the questioner believes the answerer is familiar with, in the sense that they know more about it than the questioner. Why the questioner believes that? There's probably a reason for it.

For example, if you don't speak a language, and you're talking with someone whom you believe or know speaks that language, you could ask something like:

- eigo tte yappari muzukashii?

英語ってやっぱり難しい?

English, is it difficult as I thought?

Is English hard like everybody says, or is it easy to learn?

In the case above, you haven't said eigo tte because the other person said literally the word eigo, you said eigo tte because you believe they're more familiar with that topic, so they can answer a doubt you have, or confirm something you've been wondering about.

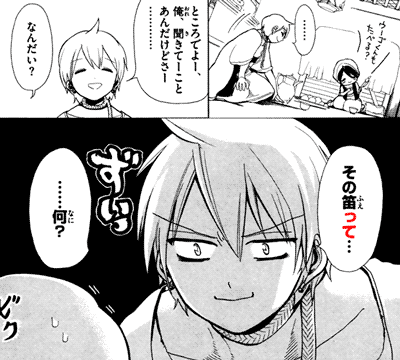

Manga: Magi: The Labyrinth of Magic, マギ (Chapter 3)

- Context: inside Aladdin's flute lives in a genie called Ugo.

- Uugo-kun mo taberu?

ウーゴくんもたべる?

Ugo-kun, too, will eat? (he's asking Ugo if he wants to eat, too.) - ......

- tokoro de yo~, ore, kikitee koto andakedo saa............

ところでよー、俺、聞きてーことあんだけどさー・・・・・・・・・・・・

By the way~, I, have something [I] want to ask you, [you know]............- Relaxed pronunciation:

- kikitee 聞きてー

kikitai 聞きたい

Want to ask. - anda あんだ

aru-n-da あるんだ

To have [something to ask].

- nandai?

なんだい?

What is it? - sono fue tte... ...... nani?

その笛って・・・・・・・・・何?

That flute......... is what?

What is that flute?- The tte って topic marker is used here because the flute is Aladdin's flute, therefore, Alibaba assumes Aladdin would be familiar with it and know stuff about it.

Recaptured Topic

The tte って particle can be used to capture a topic under new light, to talk about it with a different perspective. This is done when there's an assumption that something is true about the topic, and the sentence contradicts that assumption.How this works exactly depends greatly on who has the assumption: the speaker or the listener.

Surprising Information

The simplest case of recaptured topics are monologues: when the speaker tells themselves something, or thinks about something to themselves.In particular, it happens when the speaker had assumed something to be true, and, upon learning contradictory, surprising information, they blurt out their new findings.

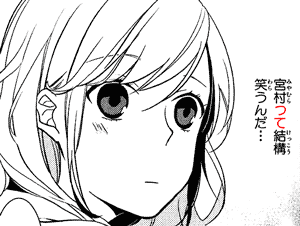

Manga: Horimiya ホリミヤ (Chapter 1)

- Context: Hori thinks Miyamura is a reserved, introverted person, who doesn't laugh a lot. Upon seeing Miyamura laugh a lot, Hori thinks:

- Miyamura tte kekkou

warau-n-da...

宮村って結構笑うんだ・・・

Miyamura laughs a lot...- The tte って topic marker is used in this monologue because the new information contradicts Hori's previous assumptions about the topic.

This usage often accompanies dakke だっけ or dattakke だったっけ when the speaker saw or heard something so incredible it made them doubt reality itself.

- kore tte kouiu mono datta kke?

これってこういうものだったっけ?

Was this this sort of thing? Am I misremembering something? Because I thought this was some other sort of thing!

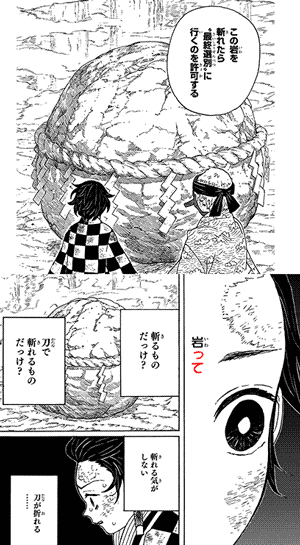

Manga: Kimetsu no Yaiba 鬼滅の刃 (Chapter 4, 炭治郎日記・前編)

- Context: Urokodaki gives Tanjirou an unrealistic goal.

- kono iwa wo kiretara {"saishuu senbetsu" ni iku} no wo kyoka suru

この岩を斬れたら“最終選別”に行くのを許可する

If [you] cut this boulder, [I] will allow {[you] to go to the final selection}. - iwa tte {kiru} mono dakke?

岩って斬るものだっけ?

Was a boulder something [you] {cut}? - {katana de kireru} mono dakke?

刀で斬れるものだっけ?

Was it something {[you] can cut with a sword}? - {kireru} ki ga shinai

斬れる気がしない

[I] don't feel like {[I] can cut it}. - katana ga oreru......

刀が折れる・・・・・・

The sword will break......

Sometimes, it comes with a question following desu ne ですね or similar sentence-ending particles used for confirming things.

Providing Information

The tte って particle can also be used when the speaker wants to provide information to the listener.This usually happens when the speaker assumes that the listener assumes something. In this case, the speaker is trying to provide information that they believe will contradict, or rather, correct the listener's assumed assumptions.

For example:(Kobayashi and Yamashita 1995:227, as cited in Suzuki, 2006:75)

- nenrei tte zenzen kankei nai desu yo

年齢って全然関係ないですよ

Age completely has no relationship to it.

Age has nothing to do with it.

Age is completely irrelevant.

The sentence above was taken from a magazine where an interviewed wife was talking about how age has nothing to do with maturity, despite one normally assuming so.

It could also be used for pretty much any situation where one assumes age is an important factor.

For example, one may assume that the terms senpai 先輩 and kouhai 後輩 have to do with age, however: age has nothing to do with it. They're about the seniority in one organization: who has been in a school, or company, for longer, not who's older.

The information provided doesn't need to be a correction. Perhaps the listener is simply clueless about everything. They don't assume, but they don't know, either. So the speaker is providing information that the speaker believes the listener doesn't know about.

Interchangeability

The tte って particle can be replaced by to wa とは and to iu no wa というのは in some cases. Both phrases feature the usual topic marker wa は and the usual quoting particle to と.For example:(Takubo, 1989:226, as cited in Suzuki, 2006:77–78)

- kimi mo bochibochi nengu no osame-doki janai no?

君もぼちぼち年貢の納め時じゃないの?

[For] you, too, soon is the time to pay land-tax, isn't it? - nengu no osame-doki to iu no wa, doo iu imi da?

年貢の納め時というのは、どういう意味だ?

What do [you] mean by "time to pay land-tax"?

Above, we have the echoic topic. Someone said a phrase, someone else asks for clarification about what that exact phrase means.

Another example:(Saito and Hisada 1999:35, as cited in Suzuki, 2006:75)

- kodomo to iu no wa,

otousan ga kigen ga warukattari suru to,

jibun ga warui-n-da mitai ni omoimasu yo

子供というのは、

お父さんが機嫌が悪かったりすると、

自分が悪いんだみたいに思いますよ

Children, when [their] father is in a bad mood, think [something] like it's [their] fault.- The to と in suru to すると is the conditional to と.

- The word warui 悪い, "bad," can mean "fault" sometimes.

Above, children were recaptured in new light. Although it's hard to tell in English, the presence of the yo よ particle in Japanese implies the speaker is telling the listener something they might not know about.

For example, say Hanako tells Tarou he's not supposed to look gloomy in from of his children. Tarou asks why. Hanako explains: because your child may think it's their fault that you're in a bad moon. That's information regarding children that Tarou didn't know about, hence the tte って particle.

By the way, the construction to iu no wa というのは is formed by the quoting to と, the verb iu いう, the nominalizer no の, and the topic marker wa は. The no の represents the event expressed by the relative clause qualifying it. Therefore, no wa のは makes the event as the topic.

In the echoic case, the event, to iu という, contains the verb "to say," iu 言う. What has been said is marked by the quoting particle to と. Who said it, that is, the subject, is implied to be the interlocutor.

- ____ to [kimi ga] iu no wa

〇〇と[君が]言うのは

As for the event: [you] said _____. - As for (は) the event (の): [you](君が) said (いう) "time to pay land-tax"(と)—what does that mean?

In the recaptured topic case, to iu is used in the sense of "called" rather than "said." This happens because, if everyone says something is something, then that thing is called something. For example, komodo to iu: the thing that people say is "children," in other words: the thing called children.

No comments: