In Japanese, the to と particle has various functions.

- Parallel Marker

- Comitative Case Marker

- Conjunction

- Quoting Particle

- Adverbializer

- Compounds

- References

Parallel Marker

The to と particle is a parallel marker that translates to "and" in English. Basically, if you have a noun or noun phrase, to can combine it with another noun or noun phrase by putting to と between them.

- neko to inu

猫と犬

Cats and dogs. - koumori no hane to hebi no o

コウモリの羽とヘビの尾

Wing of a bat and tail of a snake. - kakko-ii oujisama to kirei na ohimesama

かっこいい王子様と綺麗なお姫様

A cool prince and a pretty princess. - semeru-gawa to mamoru-gawa

攻める側と守る側

The attacking-side and the defending-side. - {benkyou suru} seito to {benkyou shinai} seito

勉強する生徒と勉強しない生徒

Students [that] {study} and students [that] {don't study}. - ao-oni to aka-oni

青鬼と赤鬼

The blue oni and the red oni. - Ookami to Koushinryou

狼と香辛料

Wolf and Spice.

(official title: Spice and Wolf.) - Kimi to Boku.

君と僕。

You and I.

When you have nouns qualified by relative clauses in parallel, an argument of the second clause can be omitted if it's recoverable from the first clause. Observe:

- {manga wo yomu} hito to {yomanai} hito

漫画を読む人と読まない人

People [who] {read manga} and people [who] {don't read [manga]}.

In the sentence above, the first relative clause, manga wo yomu, contains the direct object manga, but the second clause, yomanai, omits the direct object argument.

The same thing happens with other arguments. For example, in the relativized double-subject constructions below, the small subject is omitted in the second relative clause.

- {yuurei ga mieru} hito to {mienai} hito

幽霊が見える人と見えない人

People [who] {can see ghosts} and people [who] {can't see [ghosts]}.- sono hito wa yuurei ga mienai

その人は幽霊が見えない

About that person: ghosts aren't see-able.

That person can't see ghosts.

- sono hito wa yuurei ga mienai

- {okane no aru} hito to {nai} hito

お金のある人とない人

People [who] {have money} and people [who] {don't have [money]}.- Notes: no の subject marker, aru ある and nai ない are antonyms.

- sono hito wa okane ga nai

その人はお金がない

About that person: money is nonexistent.

That person doesn't have money.

An important note: although it translates to "and" in English, the parallel marker isn't the same thing as the English word "and." All it does is join two or more things—well, nouns and noun phrases, specifically—in a list.

For example, if you have three items, you would join them using two to と particles, but in English you would only use "and" once.

- aka to midori to ao

赤と緑と青

Red, green, and blue. - Baka to Tesuto to Shoukanjuu

バカとテストと召喚獣

Idiots, Tests, and Summoned Beasts.

The to と particle isn't the only parallel marker. There are particles that translate to "and," but that are used in different situations.

- erufu ya dowaafu

エルフやドワーフ

Elves and dwarfs, and things like that. (fantasy creatures.)- ya や lists things non-exhaustively, meaning it lists the main examples of what you're talking about, and it's implied you haven't included everything. The to と particle, by contrasts, is exhaustive.

It also doesn't match the function of the conjunctive "and" in English. This one usually translates from the te-form of verbs.

- pan wo katte taberu

パンを買って食べる

To buy bread, and eat it.

To buy and eat bread.

The main function of the parallel marker is to create a bigger noun out of two or more smaller nouns. That's simply because you can't mark two nouns in a single clause with the same case, or, less exactly: with the same particle.

For example, you can't mark two different nouns in a single clause with the wo を particle, which marks the accusative case (direct object).

- banana wo taberu

バナナを食べる

To eat a banana. - ringo wo taberu

リンゴを食べる

To eat an apple. - *banana wo ringo wo taberu

バナナをリンゴを食べる

(this is ungrammatical.) - {banana to ringo} wo taberu

バナナとリンゴを食べる

To eat {a banana and an apple}.- {ringo to banana} wo - a {noun phrase} marked with the accusative case.

Another example:

- {ken to tate} wo motte tatakau

剣と盾を持って戦う

To hold {a sword and a shield}, and fight. - {shujinkou to hiroin} ga sekai wo sukuu

主人公とヒロインが世界を救う

{The main-character and the heroine} save the world.

Noun phrases formed through parallelism, just like any other noun phrase, can become adjectives if they're marked by the no の particle. (see: no-adjectives.)

- {umi to sora} no iro

海と空の色

The color of {the sea and the sky}.- {umi to sora} no - a genitivized {noun phrase}.

Since no-adjectives qualifying nouns form noun phrases, sometimes it's ambiguous whether the parallel phrase is genitivized or if one of the parallel noun phrases contain a genitivization.

- {Tarou to Hanako} no musuko

太郎と花子の息子

The son of {Tarou and Hanako}. - Tarou to {Hanako no musuko}

〃

Tarou and {the son of Hanako}.

Tarou and {Hanako's son}.

The phrase above can be interpreted in two different ways. Depending on context, only one will make sense.

When a parallel phrase is genitivized, you can end up with a "between" instead of "of" in the translation.

- {Ten to Chi} no sa

天と地の差

The distance of {Heaven and Earth}.

A distance between {Heaven and Earth}.- A great distance. This phrase is used when two things are on completely different levels, like the introverted protagonist without friends and the most popular and beautiful girl in the school.

- {ningen to akuma} no keiyaku

人間と悪魔の契約

A contract between {a human and a demon}. - {kudamono to yasai} no chigai

果物と野菜の違い

The difference between {fruits and vegetables}.

Comitative Case Marker

The to と particle marks the comitative case, which is "with" whom you're doing something.

- Tarou ga Hanako to asobu

太郎が花子と遊ぶ

Tarou plays with Hanako.

Once again, the to と particle doesn't mean "with." It just happens to translate to "with" when it marks with whom you're doing something. One confusing case, for example, is that the de で particle marks the instrumental case: "with" what you do something.

- Tarou ga geemu de asobu

太郎がゲームで遊ぶ

Tarou plays with a game.

Generally speaking, to と marks people and animals, since doing something "with" someone means the noun marked must have agency of its own to collaborate in the action. Meanwhile, de で marks inanimate things, instruments, tools, and so on.

More specifically, this function is closely related to the parallel marking function. There are various verbs that can be said as "A and B do something" and "A does something with B." For example:

- {Tarou to Hanako} ga hanshite-iru

太郎と花子が話している

{Tarou and Hanako} are talking. - Tarou ga Hanako to hanashite-iru

太郎が花子と話している

Tarou is talking with Hanako.

Above, we have the "talking" action. When someone talks, there has to be someone to listen to them talking, someone whom they talk with, so it's a two-person action. Hence, the comitative case can be used: it means someone is accompanying the subject in a given action.

Note however, that the example 1 can be interpreted in two different ways:

- Deep-case marking.

Tarou and Hanako are talking "with" each other. - Parallel marking.

Tarou and Hanako are talking.

In the first case, example 2 and example 1 mean the same thing. Since the noun phrase marked as the subject effectively has the same meaning as the comitative case marker, it's like if the to と inside Tarou to Hanako acted as the comitative case marker instead.

In the second case, we're simply applying a predicate (are talking) to a subject (Tarou and Hanako) which constitute of two people in parallel: Tarou, and Hanako. In other words: Tarou is talking, and Hanako is talking, too. But they aren't necessarily talking to each other.

- {Tarou to Hanako} ga asonde-iru

太郎と花子が遊んでいる

{Tarou and Hanako} are playing. Are having fun.

Likewise, the sentence above can mean that Tarou and Hanako are having fun together, or that they're having fun separately, in parallel.

So the comitative case can end up inside the subject noun phrase.

- AがBとV

A does V with by B. (comitative case.) - AとBがV

A with B do V, together. (deep-case.)

A and B do V, in parallel. (parallel marker.)

The opposite, however, is invalid: we can't take a sentence that has A and B in parallel and mark B with the comitative case instead. For example(Kotani, 2001, pp. 228-229):

- {Tarou to Hanako} ga wakai

太郎と花子が若い

{Tarou and Hanako} are young. - *Tarou ga Hanako to wakai

太郎が花子と若い

*Tarou is young with Hanako. (???)

(ungrammatical.)

Similarly, you can end up with a sentence that's grammatical but doesn't make sense:

- Tarou wa {{Amerika to Kanada} ni itta} koto aru

太郎はアメリカとカナダに行ったことある

Tarou has {gone to {American and Canada}} before. - ?Tarou wa {Amerika ga Kanada to itta} koto aru

太郎はアメリカがカナダと行ったことある

Tarou has {America went with Canada} before. (what?) - {Tarou ga Hanako to itta} kuni

太郎が花子と行った国

The country [that] {Tarou went with Hanako}. (now this does make sense.)

It's also possible for the comitative case marker to mark a noun phrase containing the parallel marker.

- Tarou ga Hanako to eiga wo mi ni itta

太郎が花子と映画を観に行った

Tarou went see the movie with Hanako. - boku ga {papa to mama} to eiga wo mi ni itta

僕がパパとママと映画を観に行った

I went see the movie with {[my] dad and [my] mom}.

Although the comitative case means "with," it doesn't necessarily mean "together with" in the allied sense. It simply means one agent accompanies another agent (the subject) in an action. For example:

- Chikyuujin to Kaseijin ga tatakatte-iru

地球人と火星人が戦っている

Earthlings and Martians are fighting with each other.

Earthlings and Martians are fighting against each other. - Chikyuujin ga Kaseijin to tatakatte-iru

地球人が火星人と戦っている

Earthlings are fighting with Martians.

Earthlings are fighting against Martians.

In the sentences above, the verb tatakau takes a to と marked adversary: with whom you're fighting, in the sense of AGAINST whom you're fighting.

With verbs like these, the construction to issho ni と一緒に is used to say "together with" instead.

- Chikyuujin ga {Kaseijin to issho ni} Mokuseijin to tatakau

地球人が火星人と一緒に木星人と戦う

Earthlings, {together with Martians}, fight with Jupiterians.

Earthlings {and Martians} fight against Jupiterians.

Another example:

- shujinkou ga furyou to kenka suru

主人公が不良と喧嘩する

The main-character fight against a delinquent. (they're enemies.) - shujinkou ga {furyou to issho ni} kenka suru

主人公が不良と一緒に喧嘩する

The main-character, {together with a delinquent}, fights. (they're allies.)

This word, issho 一緒, is nothing more than a noun meaning "one group" or something like that. However, it's used with a lot of grammar to give it the "together" meaning.

- Hanako wa kareshi to issho datta

花子は彼氏と一緒だった

Hanako was together with her boyfriend.- datta - past predicative copula.

- Hanako wa {kareshi to issho ni} eiga wo mita

花子は彼氏と一緒に映画を観た

Hanako, {together with [her] boyfriend}, saw a movie.- ni - adverbial copula. See: ni に particle for details.

- ore wo {Kaseijin to issho ni} suru na!

俺を火星人と一緒にするな!

Don't make me "{together with Martians}"!

Don't put me in the same group as Martians!

Don't take me for the same as a Martian!- Used when a character compares the speaker to someone they don't like, specially by a bad feature. For example:

- Tarou's grades are horrible, but maybe you should study a bit more too.

- What?! Don't put me in the same group as Tarou! My grades are just fine!

Not all verbs that take the comitative to と in Japanese translate to "with" in English. Specially not polysemous verbs. For example:

- {Tarou to Hanako} ga tsuki-atte-iru

太郎と花子が付き合っている

{Tarou and Hanako} are dating. - Tarou ga Hanako to tsuki-atte-iru

太郎が花子と付き合っている

Tarou is dating Hanako.

The verb tsuki-au 付き合う means literally "hanging around with someone," in the sense of accompanying someone in an activity. Naturally, it takes the to と particle. However, this verb has a second meaning: "to date someone," since when two people are dating they're usually hanging around with each other.

Some other examples:

- boku to keiyaku shite, mahou shoujo ni natte yo!

僕と契約して、魔法少女になってよ!

Make a contract with me, and become a magical girl! - dare to hanashite-iru no?

誰と話しているの?

With whom are [you] talking?

Whom are [you] talking with? - Yotsuba to!

よつばと!

With Yotsuba!

Yotsuba and!- Official title: Yotsuba&.

- Although a final to と is generally the case-marking particle, in the case of Yotsuba to it's the parallel marker, as evidenced by the titles of its first three chapters, as follows:

- Yotsuba to Hikkoshi

よつばとひっこし

Yotsuba and Moving. (from one home to another.) - Yotsuba to Aisatsu

よつばとあいさつ

Yotsuba and Greetings. - Yotsuba to Chikyuu-ondan-ka

よつばと地球温暖化

Yotsuba and Global Warming.

- {shujinkou ga hiroin to kekkon suru} anime wa mezurashii

主人公がヒロインと結婚するアニメは珍しい

Anime [in which] {the main-character marries with the heroine} are rare.

- Context: Hikaru is looking for an adversary.

- aitsu to uteru?

あいつと打てる?

Can [I] [play] with [him]?- utsu 打つ

To hit.

To play. (a game like Go, in which you hit stones on a board.)

- utsu 打つ

- gata.. ガタ・・

*chair feet hitting the floor as he gets up.* (onomatopoeia.) - a, uun, ano ko wa...

あ うーん あの子は・・・

Ah, err, that kid [is]...

Comparisons

Some verbs of comparison take the comitative to と particle to say what you're comparing something "with." These verbs generally translate to English in more complicated ways.

For example, chigau 違う, "to differ," gets a "from" instead of "with.," or changes to "is different" in more natural translations.

- {kudamono to yasai} ga chigau

果物と野菜が違う

{Fruits and vegetables} differ from each other. - kudamono ga yasai to chigau

果物が野菜と違う

Fruits differ with vegetables.

Fruits are different from vegetables.

Some verbs can translate to "to" instead of "from."

- Tarou ga {ringo to orenji} wo kurabeta

太郎がリンゴとオレンジを比べた

Tarou compared {apples and oranges}.

Tarou compared {apples with oranges}.

Tarou compared {apples to oranges}.

Since it works with "is different," it makes sense that the same applies with "is the same."

- {{jibun to onaji} shumi wo motsu} hito

自分と同じ趣味を持つ人

A person [who] {has a hobby [that] {is identical with myself.}}.

Someone with a hobby [that] {is the same as mine.}.

Someone who has the same hobby that I have. - yuumeijin to nite-iru

有名人と似ている

To resemble a famous-person.

To look like a famous-person.

Note that to と is only used comparatively this way with certain verbs and words.

To compare things in general, the yori より particle is used instead.

- banana wa ringo yori oishii

バナナはリンゴより美味しい

Bananas are tasty compared to apples.

Bananas are tastier than apples.

Conjunction

The to と particle can act as a conjunction when it comes after a sentence in non-past tense, like a verb in the predicative form. This is also known as the conditional to と, and there are three different ways it's used:

- If or when something happens, something else happens.

- When I did something, I observer something else happening.

- Every time something happens something else happens.

The only difference between 1 and 2 is whether the verb of the main clause is in the past tense or not. For example:

- me ga au to sentou ga hajimaru

目が合うと戦闘が始まる

If [your] eyes meet, the battle starts.

[Your] eyes meet, and then: the battle will start. - me ga au to sentou ga hajimatta

目が合うと戦闘が始まった

[Your] eyes meet, and then: the battle has started.

Right after [your] eyes met, the battle started.- How Pokémon works.

The two sentences above describe the same sequence of events: X happens, and then, Y happens. However, in the first sentence, the verb of the matrix, hajimaru, is in non-past, "begins," "will begin," while in the second, it's in the past form, hajimatta, "has begun."

Since it "has begun" already the even has already been realized, so it already happened. Meanwhile, the non-past form means it hasn't been realized yet, so we are talking about a hypothetical case. Another example:

- furi-kaeru to yuurei ga iru kamoshirenai

振り返ると幽霊がいるかもしれない

If [I] look over [my] shoulder, maybe there will be a ghost. - furi-kaeru to yuurei ga ita

振り返ると幽霊がいた

[I] look over [my] shoulder, and then: there was a ghost.

The only difference between 3 and the others is whether the event happens only once or is recurring.

- mai-asa okiru to gyuunyuu wo nomu

毎朝起きると牛乳を飲む

Every morning, when [I] wake up, [I] drink milk.

The to と particle can't come after a clause in the past tense. In this case, the ~tara ~たら form is used instead.

- motto benkyou shitetara,

motto ii gakkou ni iketa kamoshirenai

もっと勉強してたら、

もっといい学校に行けたかもしれない

If [I] had studied more, maybe [I] would've been able to go to a better school. - gakkou ni ittara dare-mo inakatta

学校に行ったら誰もいなかった

When [I] went to school, there wasn't anybody [there].

Some other examples:

- benkyou suru to umaku naru

勉強すると上手くなる

If [you] study, [you'll] become good.

[You'll] become good if [you] study. - sou kangaeru to kantan desu ne

そう考えると簡単ですね

If [you] think that way, it's simple, isn't it?

- kusuri wo nomu to nemuku naru

薬を飲むと眠くなる

When [I] drink the medicine, [I] become sleepy.

[I] become sleepy if [I] drink the medicine. When I drink the medicine. Every time I drink the medicine. Etc. - hashiru to tsukareru

走ると疲れる

When [I] run, [I] get tired.

[I] get tired if [I] run.

- reizouko ni irenai to kusatte-shimau

冷蔵庫に入れないと腐ってしまう

If [you] don't put [it] in the freezer, [it] will rot.- reizouko ni irenai - a negative sentence.

- baka ni sareru to okoru

バカにされると怒る

If [he] gets made fun of, [he] gets mad.

[He] gets mad when [he's] taken for an idiot.- baka ni sareru - passive voice.

- baka ni suru

バカにする

To make an idiot out of [someone].

To take [someone] for an idiot.

To make fun of [someone].

- tatakawaseru to keiken-chi ga fueru

戦わせると経験値が増える

If [you] make [them] fight, the experience points increase.- tatakawaseru - causative sentence.

Quoting Particle

The to と particle can also be used in quotations, specially with verbs that take literal sentences as arguments. In this case, sometimes the Japanese quotation marks can be used, but they aren't strictly necessary. For example:

- Tarou wa "hai" to itta

太郎は「はい」と言った

Tarou said "yes." - Tarou wa hai to itta

太郎ははいと言った

Tarou said yes.

This quoting particle is used in various ways around the language. It can be used to mark one's thoughts or reasoning:

- konkai wa kore ni tsuite setsumei shiyou to omoimasu

今回はこれについて説明しようと思います

This time, [I'll] explain about this, is what [I] think.- ~you to omoimasu - this phrase is generally used to say what someone feels about doing, what they propose to be done.

- muri da to kangaete-ita

無理だと考えていた

[I] was thinking that: it's impossible.

[I] used to think that it was impossible.- muri da 無理だ

It's impossible.

- muri da 無理だ

- ore ga yatta to kan-chigai shite-iru

俺がやったと勘違いしている

[He's] wrongly thinking that: I did [it].- In other words: I didn't do it, but he's thinking that I did it.

- kan-chigai suru

勘違いする

To guess something wrong.

To perceive something wrongly.

To mistakenly think something is true.

Verbs like "said" and "thought" are often used in the passive form when talking about trivia or hearsay. For example:

- Eberesuto wa sekai de ichiban takai yama to iwarete-iru

エベレストは世界で一番高い山と言われている

It's said that: the Everest is the tallest mountain in the world.

Of course, this can be used with anything, including some stuff that would get you a [citation needed] on Wikipedia.

- Chikyuu wa hiratai to omowarete-iru

地球は平たいと思われている

It's thought that: The Earth is flat.- dare ni?

誰に?

By whom [is it thought]?

- dare ni?

One collocation featuring this function is to iu と言う, often spelled as toiu という. It's used in various ways depending on its conjugation. One of them is to say what something is called:

- kore wa neko to iu-n-da

これは猫と言うんだ

This is called a cat.- Literally:

- kore wa "neko" to iu

これは「猫」と言う

This is said: "a cat." - In the sense of that's how you say it, that's how you refer to the thing.

This is similar to the verb yobu 呼ぶ, "to call."

- kore wa {neko to yobareru} doubutsu

これは猫と呼ばれる動物

This is an animal [that] {is called a cat.}

Also similarly: the polite verb moushimasu 申します.

- watashi wa Tarou to moushimasu

私は太郎と申します

I'm called: Tarou.

The phrase toiu isn't always used to define things, sometimes it's used to introduce a new thing, or associate it to a relativized noun that categorizes it. For example:

- {Chikyuu toiu} wakusei ga taiyou no mawari ni mawatte-iru

地球という惑星が太陽の周りを回っている

A planet [that] {is called Earth} is revolving around of the sun.

The Earth, which is a planet, is revolving around the sun.

In the sentence above, the word iu いう is the verb of the relative clause {Chikyuu to iu}, which qualifies the noun wakusei, "planet." In practice, the term wakusei is categorizing what a "Chikyuu" is supposed to be. The thing called Earth, which is a planet, and so on.

- higashi niwa {Nihon toiu} kuni ga aru

東には日本という国がある

To the east, there's a country {called Japan}.

To the east, Japan, which is a country, exists.

It can also be used to refer to what someone said in the form of {to iu} no というの, literally "the thing [that] {[you] said}."

- Context: someone said a bunch of stuff that Haruhi ハルヒ never heard about.

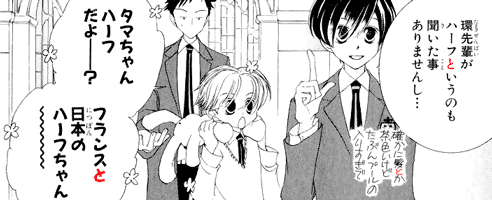

- {Tamaki-senpai ga haafu to iu} no mo {kiita} koto arimasen shi...

環先輩がハーフというのも聞いた事ありませんし・・・

That {Tamaki-senpai is a "half,"} too, [I've] never {heard about}.

[I've] never {heard about} {Tamaki-senpai being half-Japanese}, either.- koto arimasen ことありません

To have never. That has never. - shi し particle - lists a reason for saying somethnig.

- koto arimasen ことありません

- tashika ni kami toka chairoi kedo tabun puuru no hairi-sugi de

確かに髪とか茶色いけどたぶんプールの入りすぎで

It's true [his] hair and [so on] is brown but [it's] probably because [he spent too long inside the pool].- Top signs a character doesn't have two Japanese parents:

- His hair is not black.

- His eyes aren't black, either.

- puuru ni hairi-sugiru

プールに入りすぎる

To enter the pool too much.

To spend too long inside the pool. - de で particle - marks the cause of something.

- Top signs a character doesn't have two Japanese parents:

- Tama-chan φ haafu da yo----?

タマちゃんハーフだよーー?

Tama-chan is half-Japanese, [you didn't know]?- Tama-chan - Tamaki's nickname.

- Honey-senpai uses ~chan with everything.

- {Furansu to Nippon} no haafu-chan~~~~

フランスと日本のハーフちゃん~~~~

A {France and Japan's} "half"-chan.

A person half-French and half-Japanese.- Since haafu ハーフ refers to a person, it can get a honorific suffix like ~chan ~ちゃん.

Another collocation is is to ieba といえば, the conditional ba-form of to iu. This one is generally used to say what comes to mind when something is said.

- natsu to ieba umi

夏といえば海

If said "summer," sea.- In other words, the first thing you think about when someone says summer is the sea, the beach.

This particle has two variants: tte って, which is casual, and ttsu っつ, which is more like slurred word, generally used by delinquents, gyaru ギャル characters, etc.

- ore da to itte-iru no da

俺だと言っているのだ

[I'm] saying: it's me. - ore da tte itteru-n-da

俺だって言ってるんだ

(same meaning.) - ore da ttsu tte-n-da

俺だっつってんだ

(same meaning.)

Adverbializer

The to と particle sometimes functions like an adverbializer, creating random adverbs that modify the verb. There are various ways this happens, some of them probably being related to the quoting and conditional functions we've seen before.

For example, the the phrase to naru となる is used instead of ni naru になる, "to become," to emphasize it's an outcome. That is, it didn't smoothly become something, it ended up becoming so, when it could have ended up becoming something else instead. Observe:

- isha ni naru

医者になる

To become a doctor. - shippai to naru

失敗となる

To become a failure.

Clearly, you want something to become a success, not a failure. The sentence above implies it could've become a success, but something happened, and it ended up as a failure instead. Similarly:

- sensou ni naru

戦争になる

To become war. - sensou to naru

戦争となる

To end up becoming a war.- In other words, there might have been something that could have been done to avoid it, or maybe there was another choice, or maybe the diplomatic talks didn't work, anyways, it ended up becoming a war.

This to naru isn't used with na-adjectives or i-adjectives, only nouns, which suggests it's a case-marker. With adjectives, the adverbial form, or ren'youkei 連用形, is used instead.

- *kirei to naru

綺麗となる

(wrong, kirei is a na-adjective.)- kirei ni naru

綺麗になる

To become pretty.

- kirei ni naru

- *samui to naru

寒いとなる

(wrong, samui is an i-adjective.)- samuku naru

寒くなる

To become cold.

- samuku naru

It's also used with the lexical causative verb suru する, "to make become." In particular, in the form of shiyou to suru しようとする, which translates to "to try to do."

- nigeyou to shite-iru

逃げようとしている

[He] is trying to escape.- nigeru 逃げる

To escape. To run away. - nigeyou 逃げよう

Let's escape. - Although ~ou is generally used to say "let's," it's more fundamentally used to say something might be happen in the future. If the listener agrees to escape, the action of "escaping" is realized in the future, when they do, in fact, escape. Likewise, ~ou to suru means you aren't asking anybody to realize the action, you're trying to realize it by yourself.

- nigeru 逃げる

The to と particle also comes after onomatopoeia to turn them into adverbs. Since onomatopoeia are words representing sounds, this is very close to the quoting particle function.

- neko ga nyaa to naita

猫がにゃーと鳴いた

The cat made a sound: meow.

The cat meowed.- naku 鳴く

To make a sound. To cry. (animal, pokémon, etc.)

- naku 鳴く

- shinzou ga dokidoki to naru

心臓がドキドキと鳴る

The heart makes a sound: thump thump.

The heart beats loudly.- naru 鳴る

To make a sound. (inanimate objects, body parts, etc.)

- naru 鳴る

- don to kabe wo tataku

ドンと壁を叩く

To hit the wall: making a "thud" sound.

*Thud*—to hit the wall.- kabedon 壁ドン

When a guy flirts with a girl by placing his hand on a wall behind her, or vice-versa. Countless variants exist.

- kabedon 壁ドン

Similarly, the to と particle can adverbialize after mimetic words.

- pikapika to kagayaku

ピカピカと輝く

To *sparkle-sparkle* shine.

To shine sparkling. - guruguru to mawaru

ぐるぐると回る

To *swirl-swirl* spin.

To spin swirling. - betabeta to hari-tsuku

べたべたと貼り付く

To *sticky-sticky* glue-and-attach.

To glue [on something] sticking to it.

- miro yo

見ろよ

Look! - koko ni chi no ato mitai ni tenten to......

ここに血のアトみたいに点々と・・・・・・

In here, [something that] looks like blood marks [is stuck] in drops.- ato

跡

Something left behind by something else, usually as evidence.

Tracks, traces, marks, scars, etc. - tenten to

点々と

Scattered around as drops, dots, points.

- ato

Quotations, onomatopoeia, and mimetic words all work under the same conceptualization.

In Japanese, if you say "hai" to itta, "said 'yes'," then the quotation, the words said, come before the verb that means "to say." In other words, the quoting particle is doing nothing more than modifying how the verb took place: it's modifying the words spoken.

With the words "yes," he spoke. Similarly: with a *thud*, he hit the wall. With a swirling motion, it spun, with a sparkling state, it shone, and so on.

The same thing works with inanimate phonomimes (thud), animate phonomimes (meow), and phenomimes (sparkling) because they're all ideophones. And quotations are nothing more than onomatopoeia of spoken words that actually have meanings in them.

Note that while many onomatopoeia and mimetic words feature reduplication, that's not always the case.

- bon'yari to omoi-dasu

ぼんやりと思い出す

With vagueness, [I] remember.

To remember vaguely.

Furthermore, mimetic words that feature reduplication can function as adverbs without the to と particle, but their simplex forms can not(Toratani, 2007, p.317).

- hon ga batan to taoreta

本がバタンと倒れた

The book fell with a thud. - *hon ga batan taoreta

本がバタン倒れた

(the simplex batan needs to.) - hon ga batabata to taoreta

本がバタバタと倒れた

The books fell with thuds. - hon ga batabata taoreta

本がバタバタ倒れた

(same meaning, the reduplication batabata doesn't need to.)

Some mimetic words feature an embedded to と particle.

- chotto matte

ちょっと待って

To wait with-a-cho.

To wait a bit. - jitto mite-iru

じっと見ている

To be looking with-a-ji.

To stare intently.

Some to と adverbs are taru たる adjectives.

Basically, there are naru なる adjectives, like shizuka-naru 静かなる, "quiet," whose adverbial forms end in ni に, like shizuka-ni 静かに, "quietly."

And there are taru たる adjectives, like doudou-taru 堂々たる, "dignified," whose adverbial forms end in to と, like doudou-to 堂々と, "in dignified manner."

- doudou-taru kishi

堂々たる騎士

A dignified knight. - seisei-doudou-to tatakau

正々堂々と戦う

To fight in just and dignified manner.

The to と particle is also used with adverbs to emphasize "how" someone did something. In this case, since the adverb is already an adverb to begin with, there's no need to use the to と particle, unless you want emphasis. For example:

- iroiro tameshita

色々試した

Tried various things. Various ways. - iroiro to tameshita

色々と試した

(same meaning, but there's emphasis on "various." For example, maybe it only worked after and only because you've tried various things.) - dandan tsuyoku naru

段々強くなる

To gradually become stronger.

To become stronger step by step. - dandan to tsuyoku naru

段々と強くなる

To become stronger with each step. - shikkari shite kudasai

しっかりしてください

Please get a hold of [yourself].- shite is the te-form of suru, which, here, means to deliberately make yourself somehow. The adverb shikkari means "firmly" as in a firm grip, a firm hold. So make yourself firmly, get a hold of yourself.

- shikkari to shite-iru

しっかりとしている

[He's] getting a hold of [himself].- That is, shikkari, he is.

Compounds

The to と particle is part of various particle compounds.

First, it can be topicalized by the wa は particle, in which case it's often used to define things.

- Sarazanmai to wa ishiki kyouyuu

さらざんまいとは意識共有

Sarazanmai is the sharing of consciousness.

It can also be used with the contrastive wa は function.

- Hanako wa Tarou to wa asobitakunai

花子は太郎とは遊びたくない

Hanako doesn't want to play with Tarou.- Implicature: she wants to play with other people, not Tarou.

At the end of sentences, this towa とは generally implies an omitted omowanakatta 思わなかった, "didn't think."

- masaka koko made korareru to wa

omowanakatta

まさかここまで来られるとは

思わなかった

[I] didn't think that:

[you] would be able to come here.- masaka - used when something is unlikely.

- korareru - potential form of kuru, "to come."

- This phrase is used by the bad guy when the protagonist somehow beats up every single one of the middle-level bosses and makes their way to the final boss throne room.

Since to と can take the wa は particle, it can also take the mo も particle.

- Hanako wa Jirou to mo asobitakunai

花子は次郎とも遊びたくない

Hanako doesn't want to play also with Jirou.

Hanako also doesn't want to play with Jirou.- She doesn't want to play with Tarou, and she doesn't want to play with Jirou, either.

- sou to ieru

そうと言える

[You] could say [it] that way.

[You] could say that. - sou to wa ienai

そうとは言えない

[You] couldn't say [it] that way.

[You] couldn't say that.- Implicature: there's a way you can say it, and it isn't "that way."

- sou to mo ieru

そうとも言える

[You] could also say [it] that way.

[You] could also say that.

The to と particle can also combine with the ka か particle. In this case, toka とか is often a parallel marker that vaguely lists examples of something.

- isekai dewa mahou toka aru

異世界では魔法とかある

In another world, there's magic and stuff like that. - isekai dewa mahou toka doragon toka aru

異世界では魔法とかドラゴンとかある

In another world, there's magic, dragons, and stuff like that that.

References

- Kotani, Y., 2001. Disambiguation of Coordinate Expressions in Japanese by Extracting Mutual Case Relation. In Proceedings of the 16th Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation (pp. 227-236).

- と - kotobank.jp, accessed 2019-09-01.

- Toratani, K., 2007. An RRG analysis of manner adverbial mimetics. Language and Linguistics, 8(1), pp.311-342.

Hi, first of all, thank you for all your hard work ご苦労さまでした, I love your this website, and it's basically my main source for Japanese grammar, thank you so much, a few days ago I read this whole article from start to finish, but today I found a phrase with the と particle and the の at the same time, and even though your explanation here was sooo good, I had a problem understanding the phrase, can you help me please? 愛香ちゃんとの静かな時間 ( 愛香ちゃん との 静かな時間 )

ReplyDeleteThank you for reading <3

DeleteThat と means "with." The time spent "with" her. Basically, you're using ~と to qualify the noun 時間, but と can't qualify nouns by coming before them the way adjectives and verbs are able to, so the の is necessary to turn it into a no-adjective which has this function. The same principle applies to への, e.g. in 未来への手紙, "a letter to the future," 未来へ says what sort of 手紙 it is, but へ can't come before nouns to qualify them, so の is inserted between them to turn ~へ into a no-adjective.

By the way, 彼女との時間, "the time with her," could be paraphrased as 彼女と過ごした時間, "the time [I] spent with her" or 彼女と過ごす時間, "the time [i] spend with her."