In Japanese, dislocation happens when the subject or object, or other argument, comes after the verb, at the very end of the sentence, even though, normally, they're supposed to come before the verb.

More generally, in grammar, dislocation is when part of a clause, a constituent, shows up outside of that clause. In Japanese, clauses often end at the verb, so anything after that verb is outside of the clause.

Examples

Since the grammar of dislocation is kind of complicated and not actually interesting, let's start by seeing some examples of how it works.

Below, we have some dislocated sentences and their canonical counterparts

- nezumi wo tabeta yo, neko ga

ネズミを食べたよ、猫が

Ate the rat, the cat [did].- neko ga nezumi wo tabeta

猫がネズミを食べた

The cat ate the rat.

- neko ga nezumi wo tabeta

- kirei da, tsuki ga

綺麗だ、月が

Is pretty, the moon.- tsuki ga kirei da

月は綺麗だ

The moon is pretty.

- tsuki ga kirei da

- baka ka omae?

バカかお前?

Are stupid, you?- omae baka ka?

お前バカか?

Are you stupid? - omae wa baka ka?

お前は馬鹿か?

(same meaning.)

- omae baka ka?

- dare da, teeme!

誰だてめぇ!

Are who, you?!- temee wa dare da!

てめぇは誰だ!

Who are you?!

- temee wa dare da!

- oishii, kore wa

美味しい、これは

Is tasty, this.- kore wa oishii

これは美味しい

This is tasty.

- kore wa oishii

- kono saki ni ii kyuuri supotto ga aru-n-da yo.

suki daro? kyuuri.

この先にいいキュウリスポットがあるんだよ。

好きだろ?キュウリ。

There's a good cucumber spot [ahead].

[You] like, don't you? Cucumbers.- kyuuri ga suki daro?

キュウリ好きだろ?

[You] like cucumbers, don't you? - —Sarazanmai さらざんまい, Episode 6.

- kyuuri ga suki daro?

- tabun sugu shinimasu yo, ore wa

多分すぐ死にますよ俺は

(dislocation.)- ore wa tabun sugu shinimasu yo

俺は多分すぐ死にます死にますよ

I'll probably die immediately.

- ore wa tabun sugu shinimasu yo

- sosoru ze, kore wa!

唆るぜこれは!

(dislocation.)- kore wa sosoru ze

これは唆るぜ

This excites [me]. - In the sense of to excite, to stimulate, to stir up, one's curiosity, interest, or other feeling.

- kore wa kyoumi wo sosoru

これは興味を唆る

This excites [my] interest.

- kore wa sosoru ze

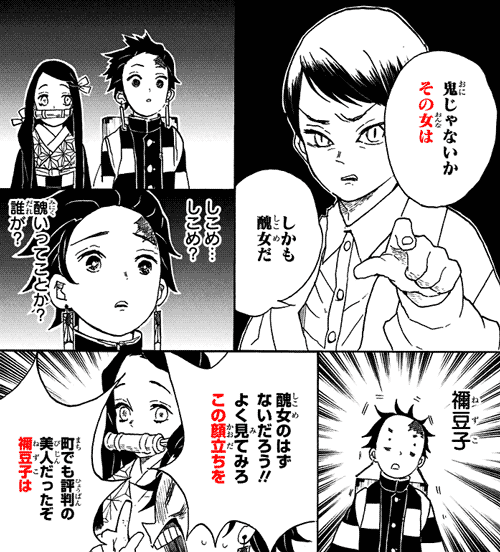

- Context: Tanjirou 炭治郎 is a good big brother who protects his little sister, Nezuko 禰豆子.

- oni janai ka, sono onna wa

鬼じゃないかその女は

(dislocation.)- sono onna wa oni janai ka

その女は鬼じゃないか

Isn't that woman an oni? - oni 鬼

A kind of demon in Japanese folklore.

- sono onna wa oni janai ka

- shikamo shikome da

しかも醜女だ

On top of that, [she] is a shikome. - shikome... shikome?

しこめ・・・しこめ?

(...) - minikui tte koto ka?

醜いってことか?

[It means] ugly?- shikome 醜女 is spelled like minikui onna 醜い女, "ugly woman." It's also a name of an ugly female demon in Japanese folklore.

- dare ga?

誰が?

Who?- This isn't a dislocation. It's an omission: who [is he saying that is ugly]? You can tell it's not a dislocation by the fact there's no verb for "to say" in this context, so it's omitted, not dislocated.

- Nezuko

禰豆子

(Tanjirou realizes this guy is calling his little sister ugly.)- The ne of Nezuko should be 礻爾, not 禰, but 礻爾 is an archaic kanji. There's no way to type it. And in modern Japanese you just use 禰 instead.

- shikome no hazu nai darou!!

醜女のはずないだろう!!

There's no way [she's] ugly, [you know]!! - yoku mite-miro, kono kao-dachi wo

よく見てみろこの顔立ちを

(dislocation, again.)- kono kao-dachi wo yoku mite-miro

この顔立ちをよく見てみろ

Try taking a good look at [her] face. - kao-dachi

顔立ち

Facial features.

- kono kao-dachi wo yoku mite-miro

- machi demo hyouban no bijin datta zo, Nezuko wa

街でも評判の美人だったぞ禰豆子は

(dislocation, for the third time in the same page.)- Nezuko wa machi demo hyouban no bijin datta zo

禰豆子は街でも評判の美人だったぞ

[Even in my hometown], [everybody agreed that] Nezuko was [a beautiful girl]. - hyouban

評判

The reputation of something, according to critics, reviewers. A restaurant that's known for being is said to have a good hyouban, or a high hyouban, it's thought highly of. - hyouban no bijin datta

評判の美人だった

Was the reputation of beautiful-person.

Was agreed (by most people) to be a beautiful-person.

Was known to be a beautiful-person. - machi de 街で

In the town. This is a scoping de で particle. In this case, Tanjirou is probably talking about the town he lived at, his hometown.

- Nezuko wa machi demo hyouban no bijin datta zo

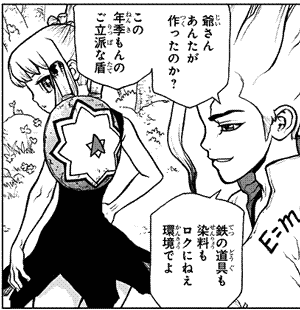

- jiisan anta ga tsukutta no ka?

爺さんあんたが作ったのか?

Old-man, did you make it? - kono nenki mon no go-rippa na tate

この年季もんのご立派な盾

This outstanding, seasoned shield.- mon もん

mono もの

Thing. - nenki 年季

Seasoned. In the sense of accustomed, well-used, well-worn. Because the shield has been used for a good while.

- mon もん

- tetsu no dougu mo senryou mo roku ni nee kankyou de yo

鉄の道具も染料もロクにねえ環境でよ

In an environment with practically no iron tools or dyes. - This whole panel contains only one sentence. The second line is headed by the word tate 盾, "shield," while the third is headed by a marked kankyou 環境, "environment." These two things are arguments for the verb tsukutta 作った, "made," from the first line.

- anta ga kono tate wo kono kankyou de tsukutta no ka?

あんたがこの縦をこの環境で作ったのか?

You made this shield in this environment?

Grammar

Syntactically, dislocation can happen in two ways, depending on the direction:

- Left dislocation.

Japanese, we're learning it.

Same as: we're learning Japanese. - Right dislocation.

They're learning Japanese, John and Mary.

Same as: John and Mary are learning Japanese.

Besides the terms above, there are other terms that refer to similar, but different things, like preposing, postposing, scrambling, movement, and so on.

- What are Right-dislocation Sentences?

Right-dislocation sentences are those in which pre-predicate elements are dislocated (i.e., postposed) to their predicate.(Nakagawa, N., Asao, Y. and Nagaya, N., 2008:1)

This article is only about right-dislocation in Japanese. Because it's the very obvious, very blatant, and easily observable one.

Statistically, sentences pretty much always end in a verb, copula or adjective, plus any sentence-ending particles in Japanese. So every time that's not the case, we can tell: yep, this is dislocated, alright. Go see a doctor.

Left-dislocation probably exists in Japanese. At very least, its been proposed that topicalization is a form of left-dislocation in Japanese, involving null pronouns and complicated stuff like that.(Murasugi, 1991, as cited in Larson, R.K. and Yamakido, H., 2003:8)

Dislocated Particles

In Japanese phrases are assigned functions in a sentence by the particles that mark them.

You only know something is the subject or the object, for example, if the ga が particle or the wo を particle is marking it. Or if the wa は particle is marking it as the topic.

Consequently, phrases dislocated to the end of the sentence must be dislocated glued to the particles that mark them. Observe:

- neko ga nezumi wo tabeta-n-da!

猫がネズミを食べたんだ!

The cat ate the rat!

If we were to move the phrase nezumi to the end, we'd end up with this:

- *neko ga wo tabeta-n-da! nezumi

猫がを食べたんだ!ネズミ

(wrong.)

If we only move nezumi, then the particle wo を ends up marking the particle ga が, and that doesn't make any sense, so the phrase is grammatically wrong. Instead, the correct way to dislocate it would be like this:

- neko ga tabeta-n-da! nezumi wo!

猫が食べたんだ!ネズミを!

The cat ate! The rat!

In the sentence above, nezumi is marked as the object of the clause headed by the verb taberu 食べる, "to eat." However, nezumi is uttered after the verb, so it's outside of the clause it's constituent of. That's called dislocation.

By the way, the -n-da んだ I used above isn't necessary for dislocation. I only used it in those examples because, without it, the sentences could be interpreted as a relative clause instead. See: {neko ga tabeta} nezumi, "the rat [that] {the cat ate}."

Scrambling

There's something very similar to dislocation that's called scrambling. The difference between scrambling and dislocation is basically that scrambling happens within the clause, while dislocation does not.

More specifically, scrambling assumes there's a standard word order, and sentences that stray from that order are said to be "scrambled."

In Japanese, the standard word order is Subject-Object-Verb. Therefore, a sentence in the Object-Subject-Verb, for example, would be considered to have been scrambled.(Harada, 1977, and Saito 1985, among others, as cited in, Murasugi, K. and Kawamura, T., 2005:131–132)

- nezumi wo neko ga tabeta-n-da!

ネズミを猫が食べたんだ!

That rat the cat ate!- This is scrambling.

- nezumi wo tabeta-n-da! neko ga!

ネズミを食べたんだ!猫が!

Ate the rat! The cat [did]!- This is dislocation.

Both scrambling and dislocation have effects on the words in non-standard order, but, technically, they're different things.

Usage

As you may have noticed already, dislocated sentences have literally the same meaning as their normal counterparts. So what's the point of using dislocation at all? Or rather, why not just say every single sentence with a dislocation?

What's the difference between a dislocated sentence and a normal one?

It seems it's a bit complicated, and there's no clear cut rule. However, there are some generalizations that do kind of apply most of the time, and I'll list them here.

First, generally, dislocation is used for clarification. Its function is often said to be for "after-thoughts," but those are after-thoughts that clarify the matrix clause, so it's clarification.

This clarification can be divided in two ways: postposing elements recoverable from context, that the speaker thinks the listener is aware of, so they're omittable, and postposing elements that are physically present.(Kuno, 1978, as cited in Nakagawa, N., Asao, Y. and Nagaya, N., 2008:3)

As it turns out, those are the same kinds of things that can be referred to using demonstrative pronouns, like the kosoado kotoba こそあど言葉, and personal pronouns. Consequently, most dislocations will end up looking like this:

- ____, kore wa

〇〇、これは

(Is something), this [thing]. - ____, koko wa

〇〇、ここは

(Is something), this place. - ____, watashi wa

〇〇、私は

(Am something), I. - ____, kare wa

〇〇彼は

(Is something), he. - And so on.

To have a better idea, let's recall what was dislocated in the examples at the start of the article:

- _____, ore wa

〇〇俺は

First person pronoun. - ____, kore wa

〇〇、これは

Demonstrative pronoun. - ____, sono onna wa

〇〇、その女は

Demonstrative pronoun.

Plus the guy is even pointing at her, it's pretty obvious who he's talking about. - ____, kono kao-dachi wo

〇〇、この顔立ちを

Demonstrative pronoun.

Plus Tanjirou is even pointing at her. - ____, Nezuko wa

〇〇、禰豆子は

Proper noun.

Again, Tajirou is literally pointing at her, it's pretty obvious he's talking about her, even if he didn't say her name. - ____, kono [...] tate

〇〇、この・・・盾

Demonstrative pronoun. - The only exception was referring to the "environment" where the shield was made. However, this, too, is omittable. That's because you simply replaced "environment without iron tools, etc." by "in this environment."

As you can see above, most of the time the dislocation will have a pronoun, because it's something recoverable from context. Even when it doesn't have a pronoun, it's usually clarifying something pretty obvious in the conversation.

For example:

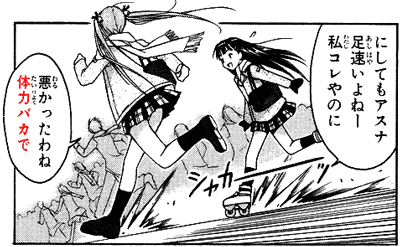

- Context: a tsundere and her friend run to school.

- ni shitemo Asuna

にしてもアスナ

[That said,] Asuna, - ashi hayai yo nee

足速いよねー- [Your] legs are fast. (literally.)

- You [run] fast.

- watashi kore ya no ni

私コレやのに

Even though [for] me, [I] have this.- This = roller-skates. She's running at the same speed the other is rollerskating.

- warukatta wa ne

悪かったわね

[Well, I'm sorry.]- This is sarcasm.

- tairyoku baka de

体力バカで

For being a physical-strength baka.- baka バカ

Stupid.

Sometimes someone that's stupidly something. In this case, someone who has a lot of stamina, endurance, agility, strength, etc.

- baka バカ

- The dislocation here is:

- {tairyoku baka de} warukatta

体力ばかで悪かった

[I'm sorry for] being a physical-strength baka. - In this case, the de で is the te-form of the da だ copula, and therefore a conjunction. This means subordinate clauses can be dislocated entirely, too.

- {tairyoku baka de} warukatta

Even though there's no pronoun in the dislocated clause above, the speaker is merely clarifying something that's already pretty obvious, and possibly known by the listener.

She's saying she's sorry, not explicitly for "running fast," but for having the physical-strength that allows her to run fast, which is basically the same thing.

One important point is that, once again generally, the focus can't be dislocated in Japanese.(Takami 1995a: 136, as cited in Nakagawa, N., Asao, Y. and Nagaya, N., 2008:5)

If you don't know what focus is, it's basically the opposite of the topic. It's new information, that the listener can't predict, as opposed to old information.

If you ask someone something, you're seeking new information, so the information asked is the focus.

- ichiban oishii no wa dore desu ka?

一番美味しいのはどれですか?

The one most delicious is which one?- ichiban oishii no wa - topic.

- dore - focus.

- dore ga ichiban oishii desu ka?

どれが一番美味しいですか?

Which one is most delicious?- dore ga - focus.

- ichiban oishii - topic.

- *ichiban oishii desu ka, dore ga?

一番美味しいですか、どれが?

(wrong.)- You can't dislocate the focus dore ga.

Similarly, the answer to somebody's question is the focus, too:

- Tarou wa Hanako ni nani wo katte-ageta no?

太郎は花子に何を買ってあげたの?

What did Tarou buy for Hanako? - #Tarou wa Hanako ni katte-yatta yo, juu-karatto no daiya no yubiwa wo

太郎は花子に買ってやったよ、10カラットのダイヤの指輪を

Tarou bought for Hanako, a ring of diamond of ten carats.- The information "a ring of diamond of ten carats" is the focus of this sentence, since it's the information that was asked in the previous sentence, and, therefore, shouldn't be dislocated.

Basically, this means that interrogative pronouns can't be dislocated in Japanese. At least no in their bare forms.

You can't say dore どれ, "which," in dislocated position, because it's an interrogation, and therefore focus, but you can say dore-mo どれも, for example, because it means "whichever" instead, and isn't necessarily the focus.

- oishii yo! dore-mo!

美味しいよ!どれも!

Is delicious! Whichever!

Whichever is delicious!

Any of them is delicious!

Every single one of them is delicious!- Note: just because dore-mo isn't "necessarily" the focus, that doesn't mean it can't be the focus.

- Once again, if someone asks you "which one is delicious," then "every one," which answers that question, would be the focus in the answer. Consequently, dore-mo would be the focus, and you shouldn't dislocate it.

- On the other hand, if someone asked you "are they delicious?" Then oishii is the focus, and you can dislocate dore-mo like the sentence above.

Once again, these are generalizations. Exceptions exist.

For example, if a sentence has multiple focus elements, one of the foci can be dislocated.(Nakagawa, N., Asao, Y. and Nagaya, N., 2008:6)

- Tanaka-san tte omiyage ni nani wo katta no? dare ni?

山田さんってお土産に何を買ったの?誰に?

What souvenirs did Tanaka-san buy? For whom? - osake wo katta rashii yo, okusan ni

お酒を買ったらしいよ、奥さんに

[I heard that] [he] bought sake, for his wife.

In the sentences above, the dative (ni-marked) foci dare ni and okusan ni are dislocated, but the object foci nani wo and osake wo aren't dislocated: they remain in the matrix clause.

Pause

It's worth noting that not all dislocated sentences feature a pause.

That is, you may have noticed that most sentences in this article feature some sort of punctuation before the dislocated element.

- miro (pause) kore

見ろ、これ

Look at, this.

Upon further inspection, you may have noticed that the manga examples feature no such punctuation. So here comes the question: do they have a pause, or they don't have a pause? And is the pause important?

According to Ono(2006, as cited in Nakagawa, N., Asao, Y. and Nagaya, N., 2008:16), there's type of right-dislocation which doesn't feature a pause, which is emotive.

- baka ka omae?!

馬鹿かお前?!

Are you stupid?!- This is said without a pause.

Basically, when the dislocation is an after-thought, when it's a clarification, the speaker said something, and then they realized what they said doesn't fully capture what they wanted to say, so they "add" something else, clarifying what they mean.

Since the speaker takes a moment to realize that, you end up with this pause between the matrix clause and the clarification.

On the other hand, an emotive dislocation doesn't feature a pause. That's because the speaker already planned on postposing the dislocated element before they started uttering the sentence.

- korosu zo temee

殺すぞてめえ

[I'll] kill you.

Punctuation

Regarding the punctuation, Japanese people, just like people from any other language, aren't really sure about which of these dotty things to use. Some people use a comma, others don't, regardless of whether there's a pause or not.

In dislocated sentences with an exclamation marks and question marks, it's common to see the mark appearing twice, once in the matrix and once in the postposed element.

- baka ka? omae?

馬鹿か?お前?

Is stupid? You? - korozu zo! temee!

頃図ぞ!てめえ!

[I'll] kill! You!

As you may have noticed, in manga a line break can be used to separate the matrix clause from the dislocated element. This is only acceptable because in manga the speech bubbles are pretty small, so it's normal to just start writing in a new line instead of using a comma.

It's possible that a space can be used to separate them, too, depending on the author.

Written Speech

In general, right-dislocation is only used in Japanese spoken speech, not in written speech. The reason for this has already been mentioned. The two use cases of dislocation are:

- Clarification.

- Emotion.

When we say "written speech" we aren't talking about text written in manga speech balloons, of course, we're talking about documents, news, reports, business e-mails, and stuff like that.

If someone needs to clarify something in a document, they'll just press backspace, delete the text, and rewrite it in a clearer way. They won't use dislocation.

Similarly, it's unlikely they'll be using the emotive function when formalities require you to write in the least emotionally charged and most professional-sounding way possible.

Dislocated Interrogatives

Perhaps the most ubiquitous and hard to explain instance of dislocation is this:

- nani kore?

なにこれ?

What is this?

This seemingly innocent two word phrase hides within a very bleak secret: it's grammatically incorrect. Or so anyone with sanity points left remaining would think.

That's because while you can say this:

- kore nani?

これなに?

(same meaning.)

Because it's the same as this with an omitted particle:

- kore wa nani?

これはなに?

(same meaning.)

You can't say this:

- *nani wa kore

なにはこれ?

(wrong.)

Because an interrogative pronoun such as nani 何, "what," can't be the topic of a sentence.

To make matters worse, if you make it the focus by marking it with ga が instead of wa は, then it doesn't even have the same meaning anymore:

- nani ga kore?

何がこれ?

What [thing] is this? (of all these things.)

What do you mean by this? (idiomatic meaning.)

And the phrase above simply is not used the way nani kore is used, or with the frequency that nani kore is used.

So what's actually happening?

Basically, a bunch of very, very angering features of the Japanese language have come together to culminate in the hardest-to-explain two word phrase syntax ever concocted by the human brain:

- kore wa nan-desu ka?

これはなんですか?

As for this, what is [it]?

What is this?- The interrogative pronoun is the focus, so it's part of the comment, while kore is the topic.

- kore wa nani?

これは何?

(same meaning.) - kore nani?

これなに?

(same meaning.)- Here, we're omitting a particle. This is possible because Japanese hates you. See: null particle.

- nan-desu ka, kore wa?

なんですか、これは?

Is what, this?- This is a dislocation.

- nani, kore wa?

何、これは?

(same meaning.) - nani kore

なにこれ

(same meaning.)

There you have it. That's how it works.

Some other examples include:

- nani sore?

なにそれ?

What's that (near you)? - nani are?

なにあれ?

What's that (far from us)? - nanda korya!

なんだこりゃ!

What's this?!- korya nanda

こりゃ何だ

(same meaning, contraction of...) - kore wa nanda?

これはなんだ

(same meaning.)

- korya nanda

- doko da koko?

どこだここ?

Where is this?- koko wa doko da?

ここはどこだ?

(same meaning.)

- koko wa doko da?

- dare da omae?

誰だお前?

Who are you?- omae wa dare da

お前は誰だ

(same meaning.)

- omae wa dare da

- nanda koitsu?

なんだこいつ?

What's [up with] this guy?- koitsu wa nanda

こいつはなんだ

(same meaning.)

- koitsu wa nanda

This is an instance of the emotive effect mentioned previously. In particular, it's used to express surprise, antipathy, or insult, rather than asking a question.(Ono and Suzuki, 1992: 439-440, as cited in Naruoka, K., 2006:486)

In other words, none of the phrases above are real questions. The speaker doesn't expect an answer for "what is this?" and so on. He probably won't get one, either. They're kind of like "what the...?" in English.

- Context: Fugo フーゴ gives Narancia ナランチャ a math question to solve.

- 16 × 55 = 28.

- *stares puzzledly.*

- nani kore......?

何これ・・・・・・?

What is this? - hehehe♡

へへへ♡

*giggle* - atatteru?

当たってる?

[Did I get it right]?- Literally "is it hitting," in the sense of hitting the mark, matching the correct answer.

- Also: the i of te-iru is contracted.

As mentioned previously, nani kore appears to be ungrammatical at first.

- [A native Japanese speaker has] the knowledge to produce an appropriately ill-formed sentence such as nani-kore? (which translates as "what is this?" but is generally considered to be a grammatically incorrect sentence) rather than an inappropriately well-formed counterpart such as kore-wa nan desu ka? ("What is this?") at a certain moment in her speech as when, for example, shocked by confrontation with something disgusting;(Tsuruta, 1996:117)

In the quote above, we can see that, at least 2 decades ago, nani kore was "generally considered to be a grammatically incorrect sentence."

One reason for this is that, when you use the copula da だ after nani なに, it becomes nanda なんだ, not nani-da なにだ. Similarly, nani-desu なにです is pronounced nandesu なんです.

- Context: a girl is conflicted.

- n? nanda.. kono kimochi wa..

ん?なんだ・・この気持ちは・・

Hm? What is it.. this feeling..- In my chest..??!!

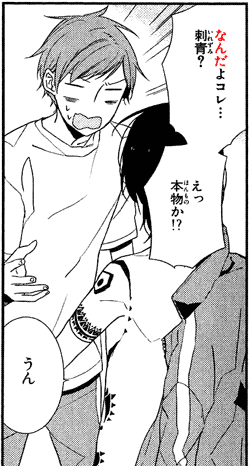

- nanda yo kore... irezumi?

なんだよコレ・・・刺青?

What is this... a tattoo? - e'? honmono ka!?

えっ?本物か!?

Eh? It's real!? - un

うん

Yeah.

The phrase nanda なんだ is easier to recognize as a dislocation because it can easily come before a sentence-ending particle like yo よ, as in nanda yo kore, so you can easily tell that the matrix clause already ended, and kore was added after its end.

However, nani kore doesn't feature the copula, so it's harder to tell what's happening. If the phrase was nani yo kore, there would be a stronger hint, but just nani kore is too short for anybody to figure out what in the world is going on with the grammar of it.

Ultimately, nani kore is grammatically correct, despite being confusing. After all, it's just nanda kore without the copula. And nanda kore is grammatical. So nani kore must be grammatical, too.

And the proof that nanda kore is grammatical is the fact that such emotive dislocation can be found in other interrogative pronouns, too, so it's not something someone just randomly said wrong, it's a feature of the language native speakers have copied and reproduced.

References

- Nakagawa, N., Asao, Y. and Nagaya, N., 2008. Information structure and intonation of right-dislocation sentences in Japanese.

- Larson, R.K. and Yamakido, H., 2003. A new form of nominal ellipsis in Japanese. Japanese/Korean Linguistics, 11.

- Murasugi, K. and Kawamura, T., 2005. On the acquisition of scrambling in Japanese. The free word order phenomenon: Its syntactic sources and diversity, 69, pp.221-242.

- Tsuruta, Y., 1996. Blind to our own language use? Raising linguistic and sociolinguistic awareness of future JSL teachers. Gender issues in language education, pp.114-125.

- Naruoka, K., 2006. The interactional functions of the Japanese demonstratives in conversation. Pragmatics. Quarterly Publication of the International Pragmatics Association (IPrA), 16(4), pp.475-512.

Impressive amount of work put into this article as always! Thank you!

ReplyDelete"Regarding the punctuation, Japanese people, just like people from any other language, aren't really sure about which of these dotty things to use"

ReplyDeleteAnd only in russian punctuation use is strictly codified, and any attempt to use wrong sign in a wrong place is punishable by death penalty.

Great article! Wouldn't you like to write something about clefting?