Among verb types, an ergative verb pair refers to an intransitive-transitive verb pair, where the subject of the intransitive is the object of the transitive, and the transitive expresses the causation of the intransitive event. Although there are some exceptions, like ditransitive verbs.

For example: ageru 上げる, "to raise," and agaru 上がる, "to rise," form an ergative verb pair both in English and in Japanese. If "you raise something" (object), you cause: "something rises." (subject)

Ergative Alternation

Ergative verb pairs generally feature ergative alternation: the process, and the ability, to switch from the intransitive verb to the transitive counterpart and vice-versa. Observe:

- Tarou ga nan'ido wo ageru

太郎が難易度を上げる

Tarou raises the level-of-difficulty. - nan'i-do ga agaru

難易度が上がる

The level-of-difficulty rises.

Above, we have the ergative verb pair ageru-agaru.

Observe that, in both sentences, the following event happens: "the level-of-difficulty rises," however, in the transitive sentence, Tarou causes it to happen, while in the intransitive sentence, there's no overt causer.

This means the intransitive sentence can mean two things:

- There's no causer at all.

The level-of-difficulty rose on its own, spontaneously. Nothing caused it to rise. It felt like rising, and then it rose. - There's an implicit causer.

Tarou causes the level-of-difficulty to rise, thus: the level-of-difficulty rises. Even if we don't explicitly say who caused it, there's the possibility that someone did cause it, and it didn't just happen spontaneously.

In Japanese, the subject and the object are marked by the ga が particle and the wo を particle respectively. These are case-marking particles. The subject is the nominative case, while the object is the accusative case.

Consequently, with few exceptions, like exchange verbs that we'll see later, most ergative verb pairs can be alternated between each other like this:

- CauserがDoerをTransitive Verb.

- DoerがIntransitive Verb.

There's a few things worth noting about terminology, because it's kind of confusing.

First, the transitive verb "causes" stuff to happen, so we have a causative sentence, however, the verb isn't conjugated to the causative form. That means it's a lexical causative verb, which is causative even without being in the causative form.

In the sentences above, level-of-difficulty undergoes the "rising" process in both sentences. This means its the "patient" in both sentences. An intransitive verb whose subject is a patient is called an unaccusative verb.

In English and some other languages, only unaccusative verbs feature ergative alternation. Intransitive verbs whose subjects aren't patients, whose subjects are agents, are called "unergative verbs," as they couldn't participate in ergative alternation.

Unfortunately, some verbs that would be called unergative, like "to cry," naku 泣く, do have causative counterparts in Japanese: nakasu 泣かす, "to cause someone to cry."

According to Perlmutter (1978:162), unergatives seem "to correspond closely to the traditional notion of active or activity." Roughly speaking, an unergative is an action that the subject voluntarily does, while an unaccusative is a process that "can" happen regardless of the subject's volition. The level-of-difficulty rises whether it wants to or not. The causer has the volition then, not the patient. The problem is: Perlmutter goes to list "certain involuntary bodily processes" that are unergative. Among those, there is "to cry." Of course, you can cry on purpose if you want, if you're an actor, acting, for a sad scene, but generally you cry without wanting to, and something or someone "causes" you to cry. I guess that's the aspect where the English and the Japanese grammar for the verb for "to cry" became split into "is unergative" and "is an ergative pair member."

Anyway, the point is: intransitive verbs aren't always unaccusative verbs, and the intransitive subjects aren't always patients. So I can't just call it "the patient" all the time.

For the sake of convenience, I'll just call the subject of the intransitive verb the "doer" from now on.

Disparity

English has more ergative verbs than ergative verb pairs, consequently, it's often the case that an ergative verb pair in Japanese will translate to a single ergative verb in English.

For example: kawaru 変わる and kaeru 変える both translate to "to change."

- sekai ga kawaru

世界が変わる

The world changes. - sekai wo kaeru

世界を変える

To change the world.

Japanese does have some lone ergative verbs, too. For example: hiraku 開く can be either causative or unaccusative depending on whether there's something marked with the accusative case or not.(Lam, 2006:265)

- Tarou ga tobira wo hiraku

太郎が扉を開く

Tarou opens the door. - tobira ga hiraku

扉が開く

The door opens.

Not all Japanese ergative verb pairs translate neatly to a single English verb. Many pairs translate to different verbs or even verb phrases.

- ito wo kiru

糸を切る

To cut a string. - ito ga kireru

糸が切れる

The string becomes cut.

The string gets cut.

- neko ga hako ni hairu

猫が箱に入る

The cat enters in the box. - Hanako ga neko wo hako ni ireru

花子が猫を箱に入れる

*Hanako "enters" the cat in the box.

Hanako puts the cat in the box.

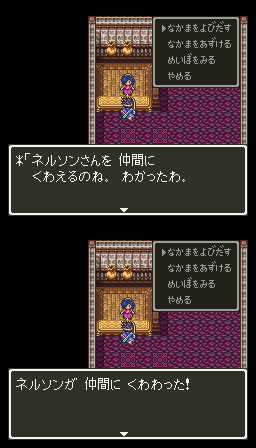

- *"Neruson-san wo nakama ni

kuwaeru no ne. wakatta wa.

*「ネルソンさんを 仲間に

くわえるのね。わかったわ。

*"Add Nelson to your party, [right]? [I got it.] - neruson ga nakama ni kuwawatta!

ネルソンが仲間にくわわった!

Nelson was added to the party!

Some verbs are polysemous: they have multiple meanings, and only one of those meanings is ergative.

For example, you can say: "Hanako enters the cat into the competition," because that meaning of enter isn't of physical movement, but of entering information into a form.

Likewise:

- Hanako ga neko wo hako kara dasu

花子が猫を箱から出す

Hanako takes the cat out of the box. - neko ga hako kara deru

猫が箱から出る

The cat gets out of the box. - neko ga hako wo deru

猫が箱を出る

The cat leaves the box.

The cat exits the box.

The verb deru is polysemous. It can be the unaccusative counterpart of dasu, or it can be a transitive verb (wo deru). Both usages mean practically the same thing. However, the unaccusative means the doer is the patient, while the transitive means the doer is the agent.

By being the agent, the doer must have agency, control over the action. That is, it's leaving the place out of their own accord. In practice, this means an inanimate doer (like blood), wouldn't take wo を with the verb deru 出る, as it will imply blood can leave places on its own.

- chi ga atama kara dete-iru

血が頭から出ている

Blood is getting out of [his] head.

[He] is bleeding out of [his] head. - chi ga atama wo dete-iru

血が頭を出ている

Blood is exiting [his] head. (is this Hataraku Saibou?)

Like the "bleeding" translation above, sometimes you also have to deal with sentences meaning special things under certain circumstances.

For example, the ergative pair for "fell on the ground" can also mean "to be defeated," just like in a fight when someone falls on the ground it's because they've been defeated.

- ki ga taoreta

木が倒れた

The tree fell-on-the-ground. - taifuu ga ki wo taoshita

台風が木を倒した

The typhoon made the tree fall-on-the-ground.

- yuusha ga maou wo taoshita

勇者が魔王を倒した

The hero makes the demon-king fall-on-the-ground.

The hero defeats the demon-king. - maou ga taoreta

魔王が倒れた

The demon-king fell-on-the-ground.

The demon-king was defeated.

Of course, the first examples could also mean the typhoon wrestled a tree and karate'd it to the ground, but that's probably not the case.

Some ergative pairs overlap with each other when one verb has two meanings, and each meaning is associated with a verb of another pair. For example:

- ito wo tsunageru

糸を繋げる

To connect the string.

To tie the string. - ito ga tsunagaru

糸が繋がる

The string gets connected.

The string gets tied.

- hito to hito wo tsunagu

人と人を繋ぐ

To connect people with people. - hito ga hito to tsunagaru

人が人と繋がる

People are connected with people.

Above, the verbs tsunageru and tsunagu share a common intransitive: tsunagaru. The difference between the causatives is that tsunageru is generally used with the meaning of "to tie" something up, rather than "to connect."

Here's another very, very intriguing example, that touches the deeper philosophical side of linguistics:

- pantsu wo miru

パンツを見る

To see panties. - pantsu ga mieru

パンツが見える

Panties can be seen. - pantsu wo miseru

パンツを見せる

To show panties.

Above, mieru, a verb regarding the visibility state of the doer, pantsu, forms ergative pairs with both miseru and miru.

It pairs with miseru because, if you show something, you cause it to become visible. It also pairs with miru, because visibility is subjective: something isn't visible (to you) unless you're actually looking at it. In other words: looking at it causes it to become visible.

Similarly, kikoeru 聞こえる, "to be heard," forms ergative pairs with both kiku 聞く, "to hear," and kikasu 聞かす, "to make hear."

Perfect and Progressive

When conjugated to the te-iru form, the verbs of a ergative verb pair tend to behave differently: the intransitive verb has a perfect meaning while the transitive verb has a progressive meaning.(Matsuzaki, 2001:145-146, citing Kindaichi 1950, Yoshikawa 1976, Okuda 1978b, Jacobsen 1982a, 1992, Takezawa 1991, Tsujimura 1996, Ogihara 1998, Shirai 1998, 2000)

This means when te-iru is used with an unaccusative, for example, it means the event already happened, and it has already changed into that state, but with te-iru, it means the action is still going on. Observe:

- kabin ga kowarete-iru

花瓶が壊れている

The flower-vase is broken. - kabin wo kowashite-iru

花瓶を壊している

To be breaking flower-vases.

With the unaccusative kowareru, the sentence means the vase broke-and-exists. That is, after it broke, it continued existing in its broken state. With kowashite-iru, however, it means someone exists breaking vases. They "are" breaking them, they were and still are breaking them.

Since this difference in meaning exists, you normally wouldn't alternate a sentence from the ergative-intransitive to the ergative-transitive if they were in te-iru form. However, it does help understand how certain te-iru sentences work.

For example, observe the following ergative pair:

- saru ga ki kara ochiru

猿が木から落ちる

The monkey falls from the tree. - Hanako ga saru wo ki kara otosu

花子が猿を木から落とす

*Hanako "falls" the monkey from the tree.

Hanako makes the monkey to fall from a tree.

Hanako drops the monkey from a tree.

If we were to assume that te-iru simply always means "-ing" in English, we would be very disappointed. That's because ochite-iru doesn't mean "falling" as we would expect.

- gomi ga ochite-iru

ゴミが落ちているYour waifu, err...

Trash is fallen.

Trash is lying on the ground.

Trash has been dropped on the ground.

The sentence above is perfect, in the sense that ochiru already happened, it's in the past, the action has been perfected already. So it can't mean "to be falling."

In order to say that something "is falling," you'd have to use the auxiliary verbs iku 行く, "to go," and kuru 来る, "to come," instead of the auxiliary verb iru いる, "to exist."

- {sora kara ochite-iku} yume

空から落ちていく夢

A dream [in which] {[you're] falling from the sky}. - {sora kara ochite-kuru} onna no ko

空から落ちてくる女の子

An girl [who] {is falling from the sky}

The difference between the two sentences above is that ochite-iku means "to go falling," in the sense of going away from where you are. If you're in an airplane and someone jumps from it, they ochite-iku.

On the other hand, if you're on the ground, and someone is falling from the sky, they're "coming," kite-iru 来ている, toward you, so they're ochite-kuru. That's how it went in Laputa, at least.

Types

There are various types of ergative verb pairs that can be observed in Japanese.

Change-of-State

The most basic ergative type is change-of-state. An unaccusative verb expresses how a patient ended up, and a causative verb expresses a causer changed the patient to that state.

- Tarou ga kabin wo kowasu

太郎が花瓶を壊す

Tarou breaks the flower-case. - kabin ga kowareru

花瓶が壊れる

The flower-vase breaks.

- Tarou ga kabin wo kowashita

太郎が花瓶を壊した

Tarou broke the vase. - kabin ga kowareta

花瓶が壊れた

The vase broke.

As mentioned previously, the intransitive verb allows the possibility that the flower-vase broke spontaneously, without a causer.

Due to this, change-of-state unaccusatives are also called inchoative verbs, in the sense that the doer begins an action on its own. The causative verb in this case is called an inchoative-causative verb. And the alternation inchoative-causative alternation.(Piñón, C., 2001, p. 346)

Of course, this is just a general rule. In practice, it's hard to imagine a situation where a vase just breaks on its own accord without a cause for it to break or a causer breaking it into pieces.(Levin and Rappaport Hovav, 1995:93, as cited in Matsuzaki, 2001:22)

IT MUST BE THE WORK OF AN ENEMY STAND.

Verbs of change-of-state can often translate to "become" or "gets."

- karada wo atatameru

体を温める

To warm up [your] body. - karada ga atatamaru

体が温まる

The body warms up.

The body becomes warmed up.

The body gets warmed up.

There are four classes of unaccusative verbs: change-of-state, appearance, existence, and inherently directed motion. Among these, only change-of-state verbs and maybe appearance can be ergative in English, while in Japanese all four classes feature ergative pairs.(Volpe, 2001:14-15.)

An ergative verb pair describing the appearance of things would be about how they look, smell, sound, etc.

- eizou ga gamen ni arawareru

映像が画面に現れる

The image appears on the screen. - puroguramaa ga gamen ni eizou wo arawasu

プログラマーが画面に映像を表す

*The programmer "appears" the image on screen.

The programmer makes an image to appear on screen.

In English you can say you "appear happy," but that's how you look, smiling, and so on. It doesn't mean the same thing as "I made happy appear," so it isn't ergative.

Existence

An existence unaccusative verb would be one that tells "there is" something somewhere somehow. Observe:

- ichi-oku-en ga ginkou kouza ni nokoru

一億円が銀行口座に残る

One million yen remain in the bank account.

There is one million yen left in the bank account. - otousan ga ginkou kouza ni ichi-oku-en wo nokosu

お父さんが銀行口座に一億円を残す

*[My] father "remained" one million yen in the bank account.

[My] father caused one million yen to remain in the bank account.

[My] father left one million yen in the bank account.

You can't use "remained one million yen" in English like the way above. Ironically, if you said "one million yen left the bank account," it means they aren't in the bank account any longer. Therefore, neither English verb is ergative.

Inherently Directed Motion

Unaccusative verbs about something moving toward a given direction can have causative counterparts where a causer causes the causee to move toward that direction.

- fune ga Hakata-futou ni tsuku

船が博多埠頭に着く

The ship arrives at Hakata port. - senchou ga Hakata-funou ni fune wo tsukeru

船長博多埠頭に船を着ける

*The captain "arrives" the ship at the Hakata port.

The captain makes the ship arrive at the Hakata port.

An interesting thing is that tsuku 着く, "to arrive" is actually an interpretation of tsuku つく, "to be attached to." Thus the pair "arrive" and "to make arrive" also means "to be attached" and "to attach." The complexity of the English translation switches around depending on the meaning.

- ribon wo kami ni tsukeru

リボンを髪につける

To attach a ribbon on [your] hair.

To wear a ribbon on [your] hair. - ribon ga kami ni tsuku

リボンが髪につく

The ribbon is attached to the hair.

The ribbon is worn on the hair.

This verb is also used with the infamous ki 気 word to form an ergative pair of idioms:

- ki ga tsuku

気がつく

To notice. To realize. - ki wo tsukeru

気をつける

To be careful. To pay attention.

The idioms above hint that ki 気 refers to your attention to things. The causative causes the attention to attach to things, in other words, you're deliberately trying to pay attention to your surroundings, to be careful. The unaccusative says you perceived something without trying to, you just noticed it.

Causation

The lexical causative verbs are often about causing something to happen, and sometimes that translates to English as just "make."

- nanika ga okiru

何かが起きる

Something will happen. - nanika wo okosu

何かを起こす

To make something happen.

- uchi no musume ga naite-iru

うちの娘が泣いている

My daughter is crying.- naku - to cry.

- {uchi no musume wo nakashita} yatsu wa yurusanai!

うちの娘を泣かした奴は許さない!

[I] won't forgive the guy [that] {made my daughter cry}!- nakasu - to make cry.

It just happens that English has a verb for it sometimes:

- sekai ga moto ni modoru

世界が元に戻る

The world returns to what-it-was-before. - sekai wo moto ni modosu

世界を元に戻す

To make the world return to what-it-was-before.

To return the world to what-it-was-before.

- moji ga kieru

文字が消える

The letters disappear. - keshi-gomu ga moji wo kesu

消しゴムが文字を消す

*The eraser "disappears" the letters.

The eraser makes the letters to disappear.

The eraser erases the letters.- keshi-gomu - literally "rubber that makes [stuff] disappear," an eraser.

- ishi ga narande-iru

石が並んでいる

The stones are forming a line.- narabu - base form.

- ishi wo narabete-iru

石を並べている

To be causing the stones to form a line.

To be arranging the stones into a line.- naraberu - base form.

Permission

A lexical causative verb can mean a permission (permissive causative) in some cases. This works under the same principle as other causative sentences: the causer inherently prohibits something to happen, and agency is necessary to allow it to happen.

For example, observe the causation below:

- men ga nobiru

麺が伸びる

The noodles elongate.

The noodles grow longer. - men wo nobasu

麺を伸ばす

To elongate the noodles.

To make the noodles longer.

Above, we're making ramen, or something like that, and we're preparing the noodles and making them longer, pulling them, stretching them with your hands and so on.

By contrast, we have this permission:

- kami ga nobiru

髪が伸びる

The hair elongates.

The hair grows longer. - kami wo nobasu

髪を伸ばす

To make your hair grow longer. (unlikely.)

To let your hair grow longer.

Your hair grows, and, normally, you cut your hair, so it doesn't grow too long. In other words, to let your hair grow means to not cut it. Inherently, you cut it, prohibiting the hair to grow, and by not doing that, you allow it grow, you cause it to grow.

Naturally, it could also mean "to make" your hair grow longer. But how are you going to do that? You can't just... pull your hair and it just keeps coming out of your head, it doesn't work like that. Similarly:

- se ga nobiru

背が伸びる

The back grows longer.

To grow taller.- se ga takai

背が高い

The back is high.

To be tall.

- se ga takai

- se wo nobasu

背を伸ばす

To make the back grow longer.

To make [yourself] grow taller.- Edward Elric's greatest dream.

Another example:

- shuujin ga nigeru

囚人が逃げる

The prisoner escapes. - shuujin wo nigasu

囚人を逃がす

To let the prisoner escape. - chansu wo nogasu

チャンスを逃す

To let a chance escape.

Above, a prisoner is escaping. Since they're a prisoner, it makes sense that you're supposed to be catching that prisoner. By not catching him, you're letting him escape.

Note that nigasu and nogasu mean slightly different things. The verb nigasu means someone is escaping and you fail to stop them, though it could also mean to release something or someone you've already captured. The verb nogasu means you fail to catch something that wasn't escaping in first place, and you just missed it.

Exchange

There are a few verbs of exchange that form ergative verb pairs but that work differently from other ergative verb pairs.

Exchange means there's a sender, an object sent (package), and a receiver. That means the causative verb is a ditransitive verb: it has a subject, a direct object, an indirect object. Consequently, we end up with a system like his:

- SenderがReceiverにPackageをSending Verb

- ReceiverがSenderからPackageをReceiving Verb.

To understand this better, let's see a few examples:

- seito ga sensei kara suugaku wo osowaru

生徒が先生から数学を教わる

The students learn math from the teacher.

The students are taught math by the teacher. - sensei ga seito ni suugaku wo oshieru

先生が生徒に数学を教える

The teacher causes: the students learn math.

The teacher teaches students math.

- Tarou ga Hanako kara okane wo kariru

太郎が花子からお金を借りる

Tarou borrows money from Hanako.

Tarou is loaned money by Hanako. - Hanako ga Tarou ni okane wo kasu

花子が太郎にお金を貸す

Hanako allows: Tarou borrows money.

Hanako lends money to Tarou.

As you can see, these are completely different from tall the ergative pairs we've seen so far in this article. Which rises the question: are these even ergative pairs? And if so, what makes them ergative verbs?

The reason why these verbs are considered ergative pairs is because one verb's existence blocks the counterpart's causativization or passivization.

That is, since a lexical causative verb like dasu 出す, "to put out," exists, you don't normally conjugate deru 出る, "leave," to its causative form, desaseru 出させる, "to make leave," because you can just use dasu instead.

Similarly, you don't use osowaraseru 教わらせる, "to make learn," because you can use oshieru 教える, "to teach," "to inform," "to tell (some information)."

And you don't use kariraseru 借りらせる, "to cause to borrow," "to let borrow," because you can use kasu 貸す, "to lend," instead.

Note that this last pair is so different from each other that even the kanji is different. In spite of that, it still forms an ergative verb pair.

The same principle applies to the verbs korosu 殺す, "to kill," and shinu 死ぬ, "to die." Since "to kill someone" means "to cause someone to die," they form an ergative pair. The causative form shinaseru 死なせる can still be used, but only in the permissive meaning: "to let someone die.""

- Tarou ga shinde-iru

太郎が死んでいる

*Tarou is dying. (no.)

Tarou is dead. (yes.)- Like intransitives of other ergative verb pairs, shinde-iru has a perfect meaning: you died, and then you stay like that, dead.

Discrepant

Some ergative verb pairs clearly share something with each other, but have discrepant meanings and thus can't actually participate in ergative alternation. For example:(Matsuzaki, 2001:122-125)

- Tarou ga suupu ni shio wo tasu

太郎がスープに塩を足す

Tarou added salt to the soup. - *suupu ni shio ga tariru

スープに塩が足りる

The salt suffices to the soup. (wrong.)

Above, the verbs tasu 足す, "to add," and tariru 足りる, "to suffice," clearly share something in their meanings: if something doesn't suffice, you keep adding more of it, until it suffices.

However, there's a discrepancy between how the verbs are used in Japanese, and that discrepancy doesn't allow the doer "salt" to alternate between verbs

Non-Lexical

It's worth noting that, with suru-verbs, ergative alternation would happen with the causative form of the light verb suru する, "to do," saseru させる, "to cause to do."

This doesn't count as a "verb pair" because it's still the same verb, it's just that you conjugated it to the causative form, but I'm including it here for the sake of completeness:

- yuusha ga sekika suru

勇者が石化する

The hero petrifies.

The hero becomes petrified. - Medwuusa ga yuusha wo sekika saseru

メドゥーサが勇者を石化させる

Medusa petrifies the hero.

Observe how, in causative sentences with verbs of change-of-state, we have practically the same thing as ergative alternation: the patient (yuusha) is marked by ga が in the unaccusative, then by wo を in the causative.

なる・する

The last pair type worth noting is naru なる and suru する. This isn't really a type of many verbs, but just a single, very noteworthy irregular pair.

The verb naru なる means "to become," while suru する, "to do," in this case, means "to make it become," "to take it as," "to decide it to be."

In essence, naru is used to talk about how something ends up as, will end up as, or has ended up as. By contrast, suru can be used to express control over the "becoming." You deliberately make something become so, or take it as so, or make it so.

- Tarou ga hitori ni naru

太郎が一人になる

Tarou will become alone. - Hanako ga Tarou wo hitori ni suru

花子が太郎を一人にする

Hanako makes Tarou become alone.

Hanako leaves Tarou alone.- In the sense that if Hanako was around Tarou, he wouldn't be alone, so she left, and now he's by himself.

- {umi ni iku} koto ni natta

海に行くことになった

It became the thing [that is] {going to the sea}.

It was decided {[we'll] go to the beach}.- For example, we were deciding what to do tomorrow, go to the mountains or to the beach, we decided to go to the beach.

- {umi ni iku} koto ni shita

海に行くことにした

[Someone] made it the thing [that is] {going to the sea}.

[Someone] made it so that {[we'll] go to the beach}.- For example, I, personally, decided we'll go to the beach tomorrow. Or the teacher decided it. Anyway, this sentence places emphasis on the fact someone deliberately made it so.

- Tarou ga baka ni naru

太郎がバカになる

Tarou becomes an idiot.

It becomes so that Tarou is an idiot. - Hanako ga Tarou wo baka ni shita

花子が太郎をバカにした

Hanako makes Tarou an idiot.

Hanako decides Tarou is an idiot.

Hanako takes Tarou for an idiot. - Tarou ga baka ni sareta

太郎がバカにされた

Tarou was made an idiot.

Tarou was taken for an idiot.

One interesting usage of this pair is with the word ki 気. Observe:

- ki ni naru

気になる

To start thinking about something. (out of your control.)

To become curious about something.

To become worried about something. - ki ni suru

気にする

To start thinking about something. (in your control.)

To bother with something. - ki ni naranai

気にならない

To not mind something. - ki ni shinai

気にしない

To ignore something.

The phrases ki ni naru and ki ni naranai express whether something is in your mind, or not, regardless of your will.

The phrases ki ni suru and ki ni shinai express whether something is in your mind, or not, and you can control it with your will.

That's why you can say ki ni suru na, "don't worry about it." Because you can stop worrying if you want. But you can't say ki ni naru na with the same negative-imperative sense, because naru is out of your control, so you can't stop it being curious even if you wanted to.

Morphology

As you've probably noticed already, most Japanese ergative pairs start with the same morpheme. That is, they start with the same syllables, and they share a similar base meaning.

For example, agaru and ageru start with this ag~ morpheme, which presumably would mean "rising" given the meaning of the verbs.

In Japanese, ergative pairs tend to start with the same kanji. After all, kanji generally represent morphemes, so it follows that two words starting with the same morpheme would also start with the same kanji that represents that morpheme: 上がる, 上げる, 切る, 切れる, 倒す, 倒れる, etc.

Some shorter verbs have differing pronunciations of the first syllable, despite being written with the same kanji. For example: ha-iru 入る and i-reru 入れる, de-ru 出る and da-su 出す. Consequently, the kanji end up having extra readings to match both words.

Causative verbs that end in ~su ~す resemble the causative form ~saseru ~させる. However, lexical causatives are different from the causative form of verbs. First, because a lexical causative verb can be further conjugated to the causative form:

- iwa ga ugoku

岩が動く

The boulder moves. - Tarou ga iwa wo ugokasu

太郎が岩を動かす

Tarou causes: the boulder moves.

Tarou moves the boulder. - Hanako ga Tarou ni iwa wo ugokasaseru

花子が太郎に岩を動かさせる

Hanako causes: Taoru causes: the boulder moves.

Hanako causes: Tarou moves the boulder.

Hanako makes Tarou move the boulder.

Second, the causative form of the intransitive is normally avoided (since the lexical causative counterpart exists), but, if used, has a difference nuance from the lexical causative counterpart.

- kodomo ga ofuro ni hairu

子供がお風呂に入る

The children enter in the bath. - Hanako ga kodomo wo ofuro ni ireru

花子が子供をお風呂に入れる

Hanako puts the children in the bath.- Lexical causative: Hanako physically grabs the children and put them into the bath. Could be used for a baby, for example, who can't enter the bath on their own.

- Hanako ga kodomo wo ofuro ni hairaseru

花子が子供をお風呂に入らせる

Hanako makes the children enter the bath.- Causative form: Hanako doesn't physically grab the children, but orders them to get in the bath, or, albeit unlikely, lets them take a bath (permissive causative).

Similarly, some intransitive verbs, ending in ~eru, resemble the passive form ~rareru ~られる. These, too, are different from the passive form. Observe:

- mizu ga nagareru

水が流れる

The water flows. - Hanako ga mizu wo nagasu

花子が水を流す

Hanako makes the water flow.

Hanako pours the water.

Hanako flushes the water. - mizu ga Hanako ni nagasareru

水が花子に流される

The water is made flow by Hanako. - *mizu ga Hanako ni nagareru

水が花子に流れる

The water flows by Hanako. (?)

(ungrammatical.)

In the example 3 above we have a sentence in passive voice, because the verb nagasareru, is in the passive form. In the passive voice, the agent is marked by the ni に particle: Hanako ni, "by Hanako."

In the example 4, we have an intransitive verb. The sentence is ungrammatical because we can't mark Hanako as the agent. Therefore, intransitive verbs differ from verbs conjugated to the passive form, despite resembling them.

Patterns

Ergative verb pairs follow certain verb-ending patterns. These can be divided into three groups, according to which one is more morphologically complex. It's assumed that the morphologically simplex verb is the origin from which the complex verb derives from.(Okutsu, 1967, as cited in Matsuzaki, 2001:54-55)

- tadouka

多動化

Transitivization.

The intransitive is simplex, the transitive derives from it.- ugoku 動く

To move.

ugokasu 動かす

To move something. - tobu 飛ぶ

To jump. To fly.

tobasu 飛ばす

To make something fly. To fling something. - waku 沸く

To boil.

wakasu 沸かす

To boil something.

- ugoku 動く

- jidouka

自動化

Intransitivization.

The transitive is simplex, the intransitive derives from it.- hasamu 挟む

To put something between. (e.g. pick something by holding it between two fingers, or to pick rice by putting it between two sticks.)

hasamaru 挟まる

To get stuck between. To be placed between. - tsunagu 繋ぐ

To connect something to.

tsunagaru 繋がる

To be connected to. - fusagu 塞ぐ

To block.

fusagaru 塞がる

To be blocked.

- hasamu 挟む

- ryoukokuka

両極化

Polarization.

Both verbs are equally complex and derive from a hypothetical root.- naoru 治る

To be healed. To heal.

naosu 治す

To heal something. To cure something.

- naoru 治る

As you can see above, there's no rule that says the longer verb is intransitive or transitive, or even that they must be of different lengths.

It's not even possible to conjugate a verb to its counterpart in the ergative pair.

For example, if you have horobiru 滅びる, "to be ruined," you can't reliably guess what its counterpart would be. Is it horoberu? Or horobisu? Nope. It's horobosu 滅ぼす, "to ruin [something]."

For reference, a list of common patterns.

- ~u and ~eru.

toku 溶く, tokeru 溶ける

To dissolve something. To be dissolved. - ~eru and ~u.

shizumeru 沈める, shizumu 沈む

To sink something. To sink. - ~eru and ~aru

ateru 当てる, ataru 当たる

To hit or touch something. To be hit or touched by.

To say something correctly. To be correctly said. - ~su and ~ru.

kaesu 返す. kaeru 返る

To return something to its original owner or place. To be returned. - ~su and ~reru.

hanasu 離す, hanareru 離れる

To separate something from. To be separated from. - ~su and ~riru

tasu 足す, tariru 足りる

To add something to. To be sufficient. - ~asu and ~u

kawakasu 乾かす, kawaku 乾く

To dry something. To dry. - ~asu and ~esu

morasu 漏らす, moreru 漏れる

To leak something. To leak. - ~asu and ~iru

mitasu 満たす, michiru 満ちる

To fill something with. To be filled with. - ~osu and ~iru

hosu 干す, hiru 干る

To hang something to dry. To be hung to dry. - ~seru and ~u

noseru 乗せる, noru 乗る

To place something atop of. To get atop of, to board (a train). - ~akasu and ~eru

obiyakasu 脅かす, obieru 脅える (see note after list.)

To frighten something. To be frightened of. - ~eru and ~oru

nukumeru 温める, nukumoru 温もる

To warm something up. To become warm. - ~eru and ~areru

wakeru 分ける, wakareru 分かれる

To divide something. To be divided.

Not all ergative pairs fall into the patterns above, but a lot of them do. The list above is a sample from Jacobsen's (1992) list, found in the appendix of Matsuzaki (2001), pages 185-194.

Note: some consonants get deleted when combined with certain vowels in Japanese. For example, although there's a ya や syllable, there's no ye. Consequently, the counterpart of moyasu 燃やす, "to burn," isn't moyeru, but just moeru 燃える, "to be burning."

Similarly, hiyasu 冷やす, "to cool," fuyasu 増やす, "to increase," hayasu 生やす, "to sprout," become hieru 冷える, fueru 増える, haeru 生える in the intransitive.

References

- Perlmutter, D.M., 1978, September. Impersonal passives and the unaccusative hypothesis. In annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (Vol. 4, pp. 157-190).

- Matsuzaki, T., 2001. Verb Meanings and Their Effects on Syntactic Behaviors: A Study with Special Reference to English and Japanese Ergative Pairs (Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida).

- Lam, Patrick P.W., 2006. Causative-inchoative Alternation of Ergative Verbs in English and Japanese: Observations from News Corpora.

- Piñón, C., 2001, October. A finer look at the causative-inchoative alternation. In Semantics and linguistic theory (Vol. 11, pp. 346-364).

- Volpe, M., 2001. The causative alternation and Japanese unaccusatives. Snippets, 4, pp.14-15.

Great article.

ReplyDeleteFrom many points intransitive verbs are like passive in english, and quite often are being translated as passive voice. Considering that Japanese tend to avoid inanimate agent in passive voice it may explain why almost every verb in Japanese has its intransitive pair. I mean "fallen by storm" is a common construction in English but you wouldn't see it in Japanese with grammatical passive voice used.