In Japanese, "female language," or joseigo 女性語, refers to words and manner of speech predominantly used by women in Japan, that, consequently, would sound weird if used by men.

It's also called "women's language," and onna-kotoba 女言葉, "women's words."

Usage

The concept of "female language" is a cultural and historical one.

In the past, certain women spoke in a certain way, which influenced how the next generations of women spoke, until we got the mess we have today.

There's nothing special about the meaning of words in female language. Everything that can be said using feminine words can also be said in a non-feminine way.

It's merely a matter that, if a lot of women speak in a way and you speak like them, you sound like you speak like a woman. And if you're a woman, then you're fitting right in and that's great. If you're not a woman, however, you'll sound unusual.

Not all female language is strictly female. Some words are simply more commonly used by women than men. Some words are used by both genders, but in one specific way used more by women. There are words that were used more by women and then started being used by men afterwards.

In anime, the use of language is often stereotypical and exaggerated: male characters often speak in a very male way, and female characters often use a lot of female language. Notably, female language in more traditional forms is often used by certain types of characters.

For example, ojousama お嬢様, "rich girl," characters often use it conspicuously, probably to hint they received a different education based on traditional manners compared to the rest of the female cast.

As do their mothers, and other rich, refined ladies. Anachronistic characters, those always wearing traditional kimonos, specially geisha and so on, often use a set of female language from their era.

Examples

First Person Pronouns

Japanese has various first-person pronouns—"I," "me"—some of which are feminine and some of which are masculine.

Feminine pronouns, typically used only by women, include:

- atashi あたし

- atakushi あたくし

- atai あたい

- uchi うち

- Also used by men in some regions of Japan.

Some pronouns can be feminine in casual contexts, but neutral in formal contexts:

Others are masculine:

If a female character uses a masculine pronoun such the above, they're labelled an orekko オレっ娘 or bokukko ボクっ娘 depending on the pronoun.

Among second-person pronouns, this one is often used by women (not toward women, by women).

- anata

あなた

You.- Can also be used by wives to refer to their "husband."

- anta

あんた

てよだわ言葉

The term te-yo-da-wa kotoba てよだわ言葉 refers to the "words te, yo, da, wa," which are often used by women at the end of their sentences.

It originated in the Meiji period (1868–1912) and is said to be the source of most female language used in modern Japanese today.

- ~te

~て

- The te-form used as an imperative is gender-neutral, but used as a question is female language.

- kaette

帰って

Go home. (neutral, imperative.) - dou nasatte?

どうなさって?

Did something happen? (female.) - dou nasaimashita ka?

どうなさいましたか? - dou ka shite?

どうかして? - dou ka nasaimashita ka?

どうかなさいましたか?

- yo

よ

- sou yo

そうよ

That's right!

- sou yo

- da wa

だわ

- muri yo

無理よ

[It] is impossible. - muri da wa

無理だわ - sou da wa

そうだわ

That's right.

It's so. - sou desu wa

そうですわ

- muri yo

Note: you may have read somewhere that the wa わ sentence-ending particle is used exclusively by women. This isn't true. Men use wa わ, too, however, to express bewilderment instead.

At Sentence End

Some other sentence-ending particles also often used by women include:

- kashira

かしら

I wonder. (sentence-ending particle.)- nani kashira?

何かしら?

What is it, I wonder? - nan-darou?

何だろう?

- nani kashira?

- ~de

~で

- akiramenaide

諦めないで

Don't give up. - akiramenai de kudasai

諦めないでください

Please don't give up.

- akiramenaide

- nasai

なさい

- benkyou shi-nasai

勉強しなさい

Go study. (neutral.) - benkyou nasai

勉強なさい

Go study. (female.)

- benkyou shi-nasai

- ne

ね

(neutral when after a copula, female otherwise.)- sou da ne

そうだね

That's right. (neutral.) - sou ne

そうね

That's right. (female.) - kirei da ne

綺麗だね

It's pretty, isn't it? (neutral.) - kirei ne

綺麗ね

It's pretty, isn't it? (female.) - muri wa ne

無理わね

Yep, it's impossible. - muri wa yo ne

無理わよね

Yep, it's impossible.

- sou da ne

- no

の

- dou natteru no?

どうなってるの?

What's going on? - watashi wa kaeru no!

私は帰るの!

I'm going home! (bye!)

- dou natteru no?

- no yo

のよ

- baka na no yo

馬鹿なのよ

[He] is an idiot.

- baka na no yo

There's a trio of words that are normally gender-neutral nominalizers, but that are used by women as sentence-ending particles instead.

- koto

こと

- {kirei na} koto desu

綺麗なことです

It's a thing [that] {is pretty}. (neutral.)

It's a pretty thing. - kirei desu koto

綺麗ですこと

It's pretty. (female.)

- {kirei na} koto desu

- mono

もの

- {kirei na} mono desu

綺麗なものです

It's a thing [that] {is pretty}. (neutral.) - kirei da mono 綺麗だもの

kirei da kara 綺麗だから

Because it's pretty. (female.)

- {kirei na} mono desu

- mon

もん

- kirei da mon

綺麗だもん

Because it's pretty.

- kirei da mon

A few other words:

- kudasai-mase

くださいませ

- kudasai-mashi

くださいまし

- kudasai-mashi

- choudai

ちょうだい

- okane choudai

お金ちょうだい

Give me money. - okane kudasai

お金ください

(same meaning.) - yamete choudai

やめてちょうだい

Please stop. - yamete kudasai

やめてください

Please stop.

- okane choudai

美化語

The o- お~ prefix is often used by women in order to create bikago 美化語, "beautified language." In the sense that simply by using the suffix the words sounds prettier (i.e. more feminine). Some examples include:

- ote

お手

Hand. Hands. - te

手 - okashi

お菓子

Sweets. - kashi

菓子

Sweets. - oniku

お肉

Meat. - niku

肉

In particular, the prefix is used in plural words for body parts featuring reduplication, which are generally used when talking to babies, presumably, by mothers more than by fathers.

- otete

お手手

Hands.

山の手言葉

Historically, old Tokyo 東京, called Edo 江戸, was divided in the upper-class, Yamanote 山の手, "mountain's hand," and the lower-class, Shitamachi 下町, "down-town."

The language used by the the upper class was called Yamanote Kotoba 山の手言葉, "mountain's hand words." In other words, the following words were used by rich ladies of the era:

- zamasu

ざます - gokigen'you

ごきげんよう

How are you? (greeting. Also used particularly used by ojousama characters in anime.) - asobasu

あそばす

ありんす詞

Another set of historic words are the arinsu-kotoba ありんす詞 used by prostitutes in the Edo period (1603–1868). It's also known as:

- kuruwa-kotoba

廓詞

Red-light district words.- A synonym for kuruwa is yuukaku 遊廓, of which Yoshiwara 吉原 was a famous one.

- sato-kotoba

里詞

Village words. Countryside words. - oiran-kotoba

花魁詞

Courtesan words.

Although this set has many historic words in it, there's really only one that's important to know about:

- arinsu

ありんす

- kirei de aru

綺麗である

It's pretty. - kirei de arimasu

綺麗であります - kirei de arinsu

綺麗でありんす - koko ni aru

ここにある

It's here. - koko ni arimasu

ここにあります - koko ni arinsu

ここにありんす - mondai ga aru

問題がある

There's a problem. - mondai ga arimasu

問題があります - mondai ga arinsu

問題がありんす

- kirei de aru

A character using this word may hint a courtesan background. For example, Yūgiri ゆうぎり from Zombieland Saga.

However, since arinsu is merely a contraction, it's not exclusively used by courtesans. There are many exceptions, even in anime, like Holo from Spice and Wolf, who is a goddess, and Shalltear from Overlord, who is a vampire.

Furthermore. arinsu comes from the polite arimasu, which means it's not used casually. For example, Tsukuyo 月詠, one of the Yoshiwara's guardians from Gintama 銀魂, uses arinsu when speaking politely with clients, which happens almost never in the series.

Interjections

There's a bunch of interjections often used by female characters in manga, for example:

- ara

あら

Oh.- arara

あらら - ara ara

あらあら

- arara

- maa

まぁ

Well. - ufu' うふっ

*giggle*- ufufu

うふふ

- ufufu

- ohoho

おほほ

*the infamous ojousama laugh* - kya' きゃっ

*shriek*

*squeal*

*fangirling noises*- kyaa

きゃー

- kyaa

- hidooi

ひどーい

- hidoi

酷い

Horrible. Cruel. Mean.

- hidoi

- iyaan

いやーん

- yaan

やーん - Literally, it's supposed to work like these:

- iya yo

嫌よ

It's unpleasant. (literally.)

Do not want. I'd rather not. No, thanks. - iya no yo

嫌のよ - Which mean you'd use it when you disagree with an idea or find something unpleasant, you don't want it.

- However, iyaan いやーん, deliberately dragged out like that, is often used in joking or flirting tone instead.

- yaan

Lastly, there's this:

- ee

ええ

Yes. No. (agrees with whatever the other person asked.)- Also used by men in formal contexts.

Male Language

The "male language," danseigo 男性語, or "men's language" is the opposite of female language: words predominantly used by men that women wouldn't normally use.

It essentially boils down to:

- Feminine words:

- Prettier.

- Polite.

- Weak.

- Masculine words:

- Uglier.

- Rude.

- Strong.

Yep, that's a lot of stereotypes. Masculine words are alright in casual contexts, but they tend to be avoided in formal contexts because they sound impolite.

Which kinda sounds like in order to present yourself as serving your superiors, your boss, your clients, and not present yourself as above them, you have to sound less masculine than usual, which hints how sexism is ingrained in society, language, and blah blah blah.

On the other hand, the idea that ladies shouldn't use filthy (masculine) words seems to be international.

Anyway, as for words that are used more by men:

- zo

ぞ

- katta zo!

勝ったぞ!

[I] won!

- katta zo!

- ze

ぜ

- issho ni ikou ze

一緒に行こうぜ

Let's go together. (how about that?)

- issho ni ikou ze

- yatsu

奴

Guy. Person.- baka na yatsu da

バカなヤツだ

[He's] an idiot guy.

- baka na yatsu da

- ano yatsu

あの奴

That guy.

- ayatsu

あやつ - aitsu

あいつ - aitsu wa baka da

あいつはバカだ

He's an idiot.

- ayatsu

- omae

お前

You. (pretty much any second-person pronoun that's not anata.) - oi

おい

Hey. (interjection.)

What are you doing? Stahp! - kora

こら

- aan? yannoka, kora?

ああん?やんのか、こら?

Ahmm? Wanna fight, huh?!

- aan? yannoka, kora?

There are many female characters that will use the words above and speak "like men" to sound strong in a fight, but the opposite never happens: nobody attempts to appear weak by using feminine words, despite the obvious strategic value in doing so. (Sun Tzu, ~500 B.C.)

オネェ言葉

The term onee-kotoba オネえ言葉 refers to female language used by male gays, transgender women, okama オカマ, and so on, but it's a bit more complicated than that. It involves a disproportional use of words like:

- yada

やだ - mou

もう - chau

ちゃう - ttara

ったら

The act of using onee-kotoba is referred to by the verb hogeru ホゲる. Some okama think you're supposed to use onee-kotoba if you're an okama, but not all think this way.

Furthermore, there are also men that aren't gay, or trans, but use onee-kotoba. They're simply called onee オネエ.

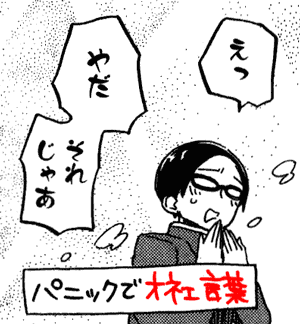

- Context: a guy panicked so hard he started speaking in onee-kotoba.

- panikku de onee-kotoba

パニックでオネェ言葉

[Using] onee-kotoba due to panic. - e' yada sore jaa

えっ やだ それじゃあ

[Eh, no way, then that means...]

In anime, okama characters often use female language or onee-kotoba, which counts as a form of gender expression.

By contrast, "trap" characters (otokonoko 男の娘) generally look and unconsciously behave femininely, but don't consciously use female language, reinforcing the idea that they ultimately identify as men in spite of being drawn like girls.

References

- 女性語 - Wikipedia.org

- Contains a list of female language words.

- 山の手言葉 - Wikipedia.org

- 男性語 - Wikipedia.org

- Sun Tzu, ~500 B.C., The Art of War.

- "Appear weak when you are strong, and strong when you are weak."

This topic was really helpful. Sometimes it's tricky to know the difference between male and female language.

ReplyDelete