In Japanese, the small katakana ke ケ, ヶ, is a bit different from the other small kana, in that it's not usually read ke, but instead as ka か, ga が, or even ko こ. Similar to how the small tsu っ isn't read as tsu つ.

For example, ni-ka-getsu 二ヶ月 is how you say "two months," as in counting the months. It's not read ni-ke-getsu despite having a ke in the middle.

Why is ヶ Read Ka か?

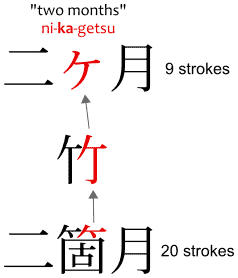

The reason why ke ヶ is read as ka in the scenario above is because it's the abbreviated way of writing a kanji. This one: ka 箇. Notice how there are two ヶ-looking components atop of it? That's the take 竹 component, literally "bamboo."(kudamatu1963)

Originally, formally, you'd write nikagetsu 二箇月, but nobody got time to write that much kanji, too many strokes, gotta go fast, that's why handwritten it would be abbreviated to nikagetsu 二ヶ月 instead.

Given this usage, it's said that this ke ヶ, or rather, ka ヶ, is not a katakana like the bigger ke ケ, but actually just a different way of writing a kanji.

That explains why you never see the small ke ヶ actually being read as ke ケ: they're totally unrelated, except for their appearance. Regardless, people still call it small ke ヶ or chiisana ke 小さなケ because that's literally what it looks like.

Some other examples:

- suukagetsu

数箇月

A number of months. Several months. - sukkagetsu

数ヶ月 - ikkasho

一箇所

One place. - ikkasho

一ヶ所

Sometimes ka か becomes kka っか, like in ikkagetsu 一ヶ月, "one month." That's due to sokuonbin 促音便.

Usage in Names

Some Japanese names contain a small ke ヶ in the middle of the kanji, sticking out like a sore thumb. In this case, the small ke ヶ is normally read as ga が instead. For example:

Some examples of characters whose names feature this:

- Senjougahara Hitagi

戦場ヶ原 ひたぎ

From the Bakemonogatari 化物語 series. - Kasumigaoka Utaha

霞ヶ丘 詩羽

From SaeKano. - Yuigahama Yui

由比ヶ浜 結衣

From OregaIru. - Kirigaya Kazuto

桐ヶ谷 和人

From Sword Art Online.

Why is ヶ Read Ga が?

If you look up in a dictionary the kanji readings of 箇, you'll see that ga が is not one of them, so how come the small ke ヶ is read as ga が?

This could be to the pronunciation of Japanese changing over time, and with them the readings of kanji. In the past, ka 箇 might have been read as ga 箇 in some words.(oshiete.goo.ne.jp:「ケ」の読みが「が」になるのは何故ですか)

But why is ga 箇 abbreviated to ga ヶ in NAMES of people? I mean, the name is probably already full of complicated kanji anyway, what's even the point of abbreviating one of them?

As it turns out, the ga ヶ in names of people isn't the counter ga 箇, but the particle ga が.

When the counter could be pronounced ga 箇, it and the ga が particle were homonyms, they had the same sound, and that seems to have been enough to write the particle the same way you would write the counter.

As for why you'd want to do that, basically particles are generally written with hiragana, but names tend to avoid using hiragana, e.g. by omitting okurigana, so that the whole name is spelled with kanji.

So writing the ga が hiragana in the name is not okay, but writing a symbol that's read as ga が instead is okay for some reason.

Finally, what does this ga ヶ particle means in the names of people? This isn't the ga が that marks the subject, nor is it the ga が conjunction that translates to "however." This is a rather archaic usage instead: the possessive ga が.

In short, it means the same thing as the no の particle that creates no-adjectives. For example: watashi 私 and ware 我 are both first person pronouns meaning "I." The possessive, "my," is watashi no 私の for watashi, and waga 我が for ware.

- watashi no na wa Megumin

私の名はめぐみん

My name is Megumin. - waga na wa Megumin

我が名はめぐみん

This ga が occurs in names of people that are actually names of places, because people used to be named after the places where they lived. The possessive is used to say that it's a place "of some sort."

For example, Akihabara 秋葉原 was once called Akiba-no-Hara 秋葉の原 or Akiba-ga-Hara 秋葉ヶ原, "Autumn Leaves' Plains." With "plains," hara 原, being a field, meadow, etc. You'll see this pattern in a lot of names of places, because they were plain plains before complicating a city onto them.

Observe how we can translate the ga ヶ in names of people from the examples of before:

- Senjou-ga-hara

戦場ヶ原 - Senjou no hara

戦場の原

Battleground's Plains.

Plains of the Battleground - Kasumi-ga-oka

霞ヶ丘 - Kasumi no oka

霞の丘

Haze's Hill.

Hill of the Haze. - Yui-ga-hama

由比ヶ浜 - Yui no hama

由比の浜

Cooperation's Beach.

Beach of Cooperation. (or something like that, according to Wikipedia's entry on the Yuigahama beach.) - Kiri-ga-ya

桐ヶ谷 - Kiri no ya

桐の谷

Paulownia Trees' "Valley" (tani 谷? Or is it a "marsh," yachi 谷内? Wait, what's a "paulownia" tree?)

Valley/Marsh of the Paulownia Trees.

Anyway, you get the point. It's usually an adjective, the ga ヶ, and a kind of place, like a plain, hill, beach, valley, marsh, or whatever.

Why is ヶ Read Ko こ?

In some cases, the small ke ヶ may be read as ko こ instead. Indeed, ka and ko are both readings of the kanji ka/ko 箇, but there's more to know about that.

You'll notice that niko 二ヶ, sanko 三ヶ, and so on mean "two things," "three things," etc. This is a counter for individual things.

Written with kanji, it would have been niko 二個, sanko 三個. That's a kinda complicated kanji, too, however, unlike 箇, 個 doesn't have a ヶ-looking component in it. So why can 個 be abbreviated to ヶ?

This seems to happen because 個 was a kanji variant of 箇(detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp:個と箇は使い分け). So words that were written with 箇, were usually written with 個 instead. For example:

- nikagetsu

二箇月

Two months. - nikagetsu

二個月

We can assume the opposite also works, and you could write niko 二個 as niko 二箇, so you could also write niko 二箇 as niko 二ヶ. But just because you could maybe do that doesn't mean you should do that. Stick to niko 二個, which is the normal way of writing "two things" in kanji.

References

- 「ヶ」はカタカナではない - https://blogs.yahoo.co.jp/kudamatu1963/62807370.html on web.archive.org

- 「ケ」の読みが「が」になるのは何故ですか? - oshiete.goo.ne.jp, accessed 2022-01-25.

- 個と箇は使い分け - detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp, accessed 2022-01-25.

I like the approach of this blog, good job dude.

ReplyDelete