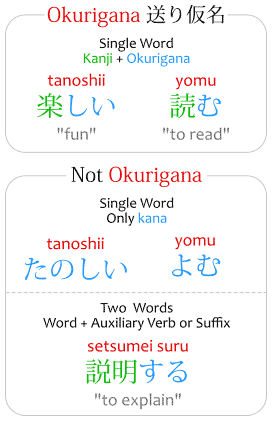

In Japanese, the okurigana 送り仮名 are the kana written after a kanji (below or at its right, depending on the writing direction) to disambiguate which word it represents.

For example: komakai 細かい and hosoi 細い, "small" and "thin," are written with the same kanji, but its reading and meaning changes depending on the okurigana.

A word written only with kana never has okurigana, by definition, as okurigana only refers to kana after kanji (no kanji, no okurigana). Also, a suffix, auxiliary verb, or second word written with kana after a word written with kanji is not an okurigana. (example: suru する is not an okurigana, despite frequently coming after kanji)

Purpose

The main purpose of okurigana is to differentiate between words written with kanji by hinting the reading of the kanji. This function is similar to the furigana 振り仮名, however there are some differences.

First, the furigana explicitly tells the reading of the kanji itself. The okurigana only tells the ending of the reading, which helps determine which word it is, and therefore the whole reading of the word.

Second, the furigana may contain virtually any text, even if it's not the reading of the kanji, mainly for artistic reasons. Meanwhile, the okurigana must be the kana associated with a reading of the kanji, since you use the okurigana to figure out the whole reading. In other words, okurigana has a standard to follow.

For a given word, there is a number of proper okurigana, which you can find in the dictionary, and writing a different okurigana would be considered a misspelling, an error.

For example, 横る would be an error, because in the dictionary there is no reading for the 横 kanji that is followed by the る okurigana.

Alterations in Okurigana

Like all language things, okurigana isn't permanent. Sometimes the official spelling of the word may change for reasons and so the okurigana changes too.

One interesting case is the word sukunai 少ない, "few." In the past, the okurigana was different, and the word was written as sukunai 少い. Note the na な isn't part of the okurigana.

The change happened, apparently, because to say "not (i-adjective)" you'd turn the i い of the adjective into ku く and add the auxiliary suffix nai ない. For example: chiisai 小さい, "small," becomes "not small," chiisakunai 小さくない.

In the case of sukunai 少ない, "few," it already ends with kunai in its affirmative (positive) form. The negative form would be: sukunakunai 少なくない, "not few." With the old okurigana, it'd change from 少い to 少くない, and you could mistake positive with negative if you read the kanji as just su instead of sukuna. With the new suku reading that's not a problem. See:

- sukuna.i 少い (old affirmative)

- sukuna,kunai 少くない (negative)

- su.kunai 少くない (mistake!)

- suku.nai 少ない (new affirmative)

- suku.nakunai 少なくない (negative)

(you can't mistake it now!)

Examples of Okurigana

Some very good examples of okurigana:

- hanashi

話

A conversation. A story. (noun) - hanasu

話す

To talk with. To tell a story. (verb) - hanashi

話し

The act of talking with, or of telling a story. (noun from the verb above).

- oriru

降りる

To descend. To go down.

To step down (leave a job, position). - furu

降る

To rain.

- ageru

上げる

To raise.

To give. - noboru

上る

To climb.

The okurigana helps differentiate between transitive and intransitive verbs in ergative verb pairs:

- deru

出る

To leave. - dasu

出す

To take out. (to make something leave) - magaru

曲がる

To curve. - mageru

曲げる

To curve something.

Okurigana vs. Inflections

The okurigana is often found in verbs and adjectives as the kana is used to inflect (conjugate) them.

Note, however, that the term okurigana does not refer to the part that can be inflected in a word. It just happens to be that part. The okurigana is always just the kana after the kanji in a word, used to determinate the reading of the kanji.

There are words with okurigana that are nouns or adverbs. For example: tashika 確か, "indeed," is neither a verb nor an adjective but has okurigana.

Furthermore, a verb written without kanji, like itta いった, "said," does not have okurigana, only when it's written with kanji, itta 言った, that the tta gets called okurigana.

With Kun'yomi

Historically, the okurigana is meant to be used with kun'yomi readings of kanji. That is, with Japanese words that ended up being written with kanji, because multiple words were assigned the same kanji, okurigana was used to disambiguate the reading, and, consequently, the meaning and word.

This means that the kanji of a word such osoi 遅い, this "遅" kanji, has the kun'yomi reading of osoi, the whole thing, including the i. Even though when it's written it looks like the 遅 kanji is read as oso 遅 and there's an i い in front of it, so you'd think the kun'yomi reading is just oso.

In reality, the kun'yomi are how Japanese words are read, so 遅 has the kun'yomi readings (represents the Japanese words) osoi, "slow," and okureru, "to be late." The okurigana disambiguates the exact word: osoi 遅い if the okurigana is い, and okureru 遅れる if the okurigana is れる.

With On'yomi

Most words that have on'yomi readings of kanji do not have okurigana, since those are not based on Japanese, but on Chinese.

A couple of notes:

First, suru is not okurigana, it's an auxiliary verb. So kekkon suru 結婚する, "to marry," has no okurigana, even though there are kana after the kanji. Because those are two separate words (kekkon and suru) and not a single word mixing kanji and kana.

Second, jiru じる might be okurigana (I'm not very sure, but it seems it technically is, at least according to mfuji-san on HiNative: 信じる」や「感じる」などで「じ」とは、送り仮名でしょう?).

So words like kanjiru 感じる, "to feel," shinjiru 信じる, "to believe," and kanji 感じ, "feeling," do have okurigana despite the kanji being read with on'yomi.

However, jiru じる comes from zuru ずる, an old way to say suru する with a rendaku 連濁 pronunciation. That is: instead of shin suru 信する, it was said shinzuru 信ずる, and now, in modern Japanese, it became shinjiru 信じる.

So, although suru is not okurigana, jiru, which originates from suru, is okurigana. Not that any of these technicalities matter, though.

Words Written Without Okurigana

Sometimes, a word which is normally written with okurigana ends up being written without the okurigana, which can be misleading.

That's because words with okurigana often have kun'yomi readings, therefore, you'd assume the lack of okurigana implies the word should be read with the on'yomi reading, but if the okurigana is deliberated omitted, it's then a kun'yomi reading without okurigana.

For example: arigatou 有難う and arigatou 有り難う. It's the same word, but the first one is missing the okurigana for the ari 有.

This phenomenon tends to occurs with the ren'youkei 連用形 of verbs, which is the noun form. For example, hikaru 光る means "to shine," so a hikari 光り is "something that shines," normally meaning a "light," spelled without okurigana, as hikari 光.

- Context: Hirose Koichi 広瀬康一 enters somewhere he shouldn't.

- tachi-iri-kinshi

立入禁止 (not 立ち入り禁止)

Entry forbidden.

No trespassing.- tachi-iru

立ち入る

To enter. To trespass.

- tachi-iru

The okurigana is a hint to help the reader figure out which is the right kun'yomi reading of the kanji, and consequently what is the right word and meaning. The okurigana is not absolutely required in all cases, it's just the normal way to write.

If people see 後 without okurigana, they'll assume it's ato 後, or nochi 後, or go 後, they won't assume it's ushiro 後, because that's written with okurigana: ushiro 後ろ. However, 後 can be read as ushiro in a context where you already know that that is the word the kanji is representing. This doesn't happen often, but it can happen.

The Kanji Alone Represents The Word

There are situations where one would prefer, for stylistic reasons, for aesthetic, to write the Japanese word with kanji, because kanji looks prettier, more complex than kana. A single kanji is more visually pleasant in its design than an unbalanced mess of kanji and okurigana.

For example, instead of writing kachi 勝ち, "victory," someone might write the kanji alone 勝, and it'd be read as kachi, since the kanji represents the word "victory," which is kachi.

An example in the anime fandom: the BL terms seme and uke are written as 攻め and 受け with okurigana, but they may also be written with the kanji alone: 攻 and 受.

No comments: