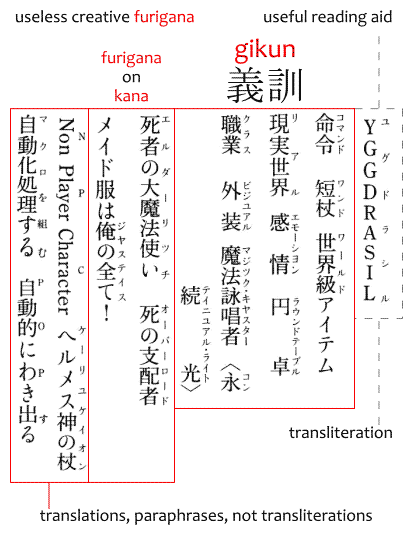

In Japanese, gikun 義訓, meaning "artificial kun'yomi reading," refers to writing a different word in the furigana 振り仮名 space (a.k.a. in the ruby text). More technically, it refers to giving a kanji 漢字 a non-standard reading that only makes sense in a given context.

Purpose

Broadly speaking, gikun is a typographic technique that allows an author to write two words or phrases at once, side by side, thereby associating one phrase with the other. An easy to understand example would be something like this:

- Writing "we" beside "humankind" to mean that "we" refer to the whole "humankind."

- (wareware) jinrui

人類

(We) the humankind.

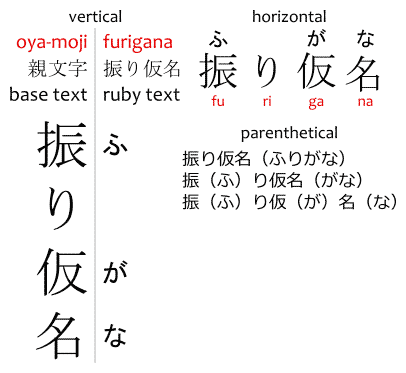

This is possible because Japanese has reading aids, the furigana.

The furigana are, normally, kana 仮名 characters (the hiragana ひらがな and katakana カタカナ), that show how to read a word.

The furigana is written atop or beside the base text it annotates, according to the direction Japanese is written. When that's not possible, it's written in parentheses after the base text.

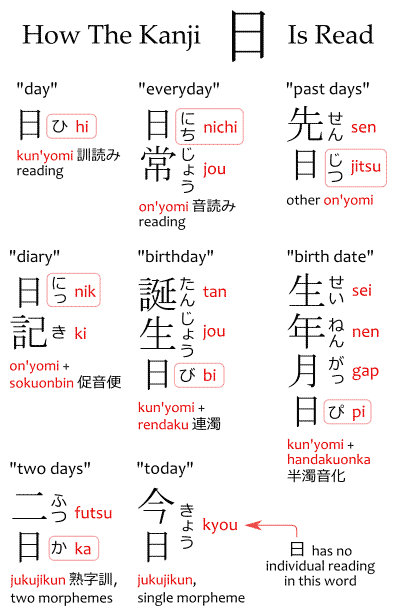

The reason why reading aids EXIST in Japanese is because a single kanji has multiple readings, that is, a single kanji can be read in different ways depending on the word it's part of.

The important thing about reading aids is that the same word is always going to have the same reading aid regardless of context. After all, it's always going to be the same word.

As such, jinrui 人類 always gets jinrui じんるい as furigana, because it's always read jinrui, because the word is jinrui. No matter what book you read, the furigana for jinrui is always jinrui, and once you memorize that, you don't need the furigana anymore.

The gikun is when the furigana isn't a reading aid

If jinrui has wareware as furigana for some reason, that's not a reading aid added to teach you how to read the word, that's a creative use, a gikun, added to make you go on the internet ask "why is the furigana for this word wrong?"

The exact definition of gikun doesn't matter much, and we'll see it in detail later at the end of the article.

The point is that what we're calling gikun is when an author makes use of a typographic device of the Japanese language to connect two random words or even phrases by writing both of them at once.

English, and many other languages, don't have something like furigana, because they don't have something like kanji, and, consequently, they don't have something like gikun.

It's not possible to translate a gikun to such languages. The best we can do is use parentheses. But there's a bit of a problem involving them.

When parentheses are used to write the furigana in a single line in Japanese, the reading aid comes AFTER the word it annotates. Like this:

- 人類(じんるい)

You read vertical text right-to-left, and the furigana goes to the right side of the word, which means the furigana is supposed to be read BEFORE the word it annotates.

This isn't a problem with reading aids since they mean the same thing, but with gikun it's a problem because you'll have two different words, so which one comes first: the base text, or the furigana?

- jinrui (wareware)

- (wareware) jinrui

Personally, I think the furigana coming first makes more sense.

The furigana is how you read the word. This is also true for gikun. If the furigana says wareware, you read the word wareware. It doesn't matter what the base text says, what the dictionary says, or what the internet says. The furigana is the author telling you: "you read it like THIS."

If the furigana is how you read it, then what's the role of the base text? The base text contains a meaning for the gikun. If the gikun is meaningless gibberish, the base text tells what it means, and if the gikun is a meaningful word, the base text is a synonym, paraphrase, or translation of it.

It makes more sense to say that "wareware means jinrui in this context" than to reverse it and say "jinrui is read wareware here." After all, it isn't just a matter of reading, but also of adding a secondary meaning to the phrase pronounced.

Examples

For reference, some examples of gikun.

Fictional Made-up Readings for Kanji

In shounen manga, light novels, games, and other fiction, it's awfully common to use foreign words for all sorts of techniques, attacks, items, locations, organizations, entities, and so on, because it sounds cooler. These made-up fictional words are also given kanji by their authors, turning them into gikun.

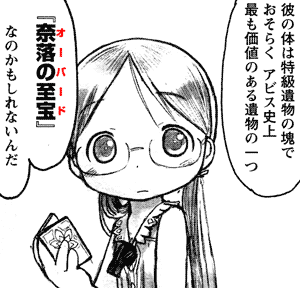

- Context: in a series about searching for relics in a bottomless pit called the Abyss, Riko リコ is told some important information about a robot boy she found in the Abyss.

- {kare no karada wa tokkyuu ibutsu no katamari de}, osoraku, {Abisu shijou mottomo kachi no aru} ibutsu no hitotsu "Naraku no Shihou (Oobaado)" na no kamoshirenai-n-da

彼の体は特級特急遺物の塊でおそらく アビス史上最も価値のある遺物の一つ「奈落の至宝」なのかもしれないんだ

{His body is a bunch of special-grade relics, and}, likely, could be one of the relics {of most value in all of the Abyss' history}, an "(Aubade) Precious Treasure of The Abyss."- Here, Oobaado is used as gikun for Naraku no Shihou, because the name for the thing in this series is "Aubade," and what the word means is "Precious Treasure of The Abyss."

- Context: good guy with mechanical arm fights bad guy with mechanical arm.

- o'

おっ

Oh! - (ootomeeru) kikai-yoroi nakama?

機械鎧仲間?

[You're] (automail) mechanical armor nakama?

[You too have an] automail?- nakama 仲間, "comrade," here used in the sense of also having an "automail," which is the in-universe term for prosthetic limbs.

Chuunibyou Usage

As a consequence of gikun being used manga and games, edgelord chuunibyou 中二病 characters also have a tendency of using them

Bottom: Cerberus ケルベロス

Anime: Boku no Tonari ni Ankoku Hakaishin ga Imasu. ぼくのとなりに暗黒破壊神がいます。 (Episode 1)

- Context: when Sturmhut removes his eye patch, the "Dark God of Destruction, Miguel Offenbarung Dunkelheit Wahnsinn Äußerst Gefallener Engel Abgrund Nachfolger," Ankoku Hakaishin Migeru (Offenbārungu) Mokushiroku (Dhunkeruhaito) Yami (Vānzuin) Kyouki (Oisāsuto) Kyuukyoku (Gefarenāengeru) Datenshi (Appugurunto) Naraku (Nāhaforugā) Koukeisha 暗黒破壊神ミゲル・黙示録・闇・狂気・究極・堕天使・奈落・後継者, awakens.

- Everything after Miguel is gikun. They're just random, edgy words in German. For reference:

- mokushiroku

黙示録

Apocalypse. (Offenbarung) - yami

闇

Darkness. (Dunkelheit) - kyouki

狂気

Insanity. (Wahnsinn) - kyuukyoku

究極

Ultimate. (Äußerst) - datenshi

堕天使

Fallen angel. (Gefallener Engel) - naraku

奈落

Abyss. (Abgrund) - koukeisha

後継者

Successor. (Nachfolger)

Synonymous Paraphrases

In some cases, the furigana and the base text mean the same thing, but use different words, that is, the gikun is a paraphrase of the base text.

- (tada) muryou

無料

(For free) without charge.- muryou - the antonym of yuuryou 有料, "with charge," i.e. that costs money, isn't free.

- tada - only, just, for free.

- (maji) honki

本気

[He's] (for real) serious [about it].- honki - to be serious about doing something.

- maji - for real (slang).

Foreign Text Translations

The gikun may be a non-Japanese phrase that is pronounced out loud, while the base text is what that phrase means in Japanese, i.e. the base text is the Japanese translation of the gikun.

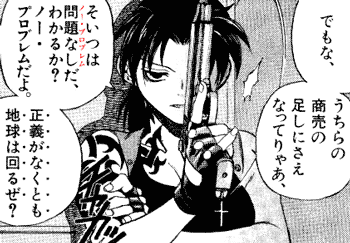

- Context: Revy レヴィ explains how professionals work.

- demo na, uchi-ra no shoubai no tashi ni sae natte-ryaa,

でもな、うちらの商売の足しにさえなってりゃあ、

But [you see], if [it] helps our business,- uchi-ra no - "our."

- natteryaa - contraction of natte-ireba なっていれば.

- tashi ni naru

足しになる

To be useful (for something.)

- soitsu wa (noo-puroberumu) mondai-nashi da,

そいつは問題なしだ

That one is no problem (no problem).- She sometimes mixes English phrases in the Japanese.

- Here, she says noo puroberumu, a katakanization of "no problem."

- The Japanese phrase, mondai-nashi 問題なし, works as a translation for the Japanese readers that might not understand what the English ノー・プロベルム means.

- wakaru ka?

わかるか?

{Do you get it?] - noo-puroberumu da

ノー・プロベルムだ

No problem.- This second time doesn't get a gikun, because the reader will already know what the phrase means.

- seigi ga nakutomo tikyuu wa mawaru ze?

正義がなくとも地球は回るぜ?

Even without justice the world [goes round].- The world doesn't stop just because of injustices.

- The dots in the furigana emphasize what she's saying.

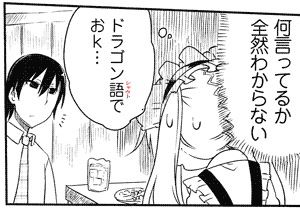

- Context: a dragon maid doesn't understand a guy.

- nani itteru ka zenzen wakaranai

何言ってるか全然わからない

[I] have no idea what [he] is saying. - doragon (shauto) go de ookee...

ドラゴン語でおk・・・

With dragon (shout) language [it] is OK. (literally.)

Can you say that again in dragon (shout) language?- This is a reference to a meme.

- nihongo de ok

日本語でおk

With Japanese language, it's ok. - Which normally would be used if someone is speaking English or Greek or something, and a Japanese native that doesn't understand those languages would rather have them speak in Japanese.

- From there, the meme is used when someone is saying stuff that you can't understand, full of jargon, so it sounds like a different language to you.

- Context: the first chapter of Overlord uses furigana creatively a lot. Overlord is a story about a character who playing a virtual reality MMORPG.

- yugudorashiru

YGGDRASIL

- Here, the furigana is a katakanization of the Latin script. While furigana used like this is unusual, it's a reading aid, not a creative use.

- (komando) meirei

命令

(Command) order.- This and examples below are game terms that are in katakanizations of English words being spelled with kanji that mean basically—and sometimes literally—the same thing in Japanese.

- They're all gikun, since it's the spelling that is used in THIS GAME specifically, and not outside this context.

- In this case, a "command" is an "order" given to an NPC.

- (tanjou) wando

短杖

("Short stick," wand) wand. - (waarudo) sekai-kyuu aitemu

世界級アイテム

(World) world-level item.- This term is read "world item," with sekai-kyuu, "world level," being a high item level.

- (riaru) genjitsu sekai

現実世界

(Real) real world.- riaru, a katakanization of "real," is a Japanese slang referring to real life, as opposed virtual life, on a virtual world, like in an online game, or online forum, etc.

- (emooshon) kanjou

感情

(Emotion) emotion. - (raundo-teeburu) entaku

円卓

(Round table) round table.- As in "knights of the round table," entaku no kishi-dan 円卓の騎士団.

- (kurasu) shokugyou

職業

(Class) job.- In RPGs, the term "class" or "job" refers to a role a character has that defines their abilities, such as the "mage" class having magic abilities, or the "knight" class using a sword, etc.

- (bijuaru) gaisou

外装

(Visual) exterior.- In the sense of how a character looks, with certain appearance settings, cosmetic items equipped, etc.

- (majikku-kyasutaa) mahou eishou-sha

魔法詠唱者

(Magic caster) magic chanter.- A mage class in this game.

- (konthinyuaru-raito)

<永続光>

(Continual light) persisting light.- The name of a magic spell in this game.

- This word is excerpted as-is: in the page it was found, the line wraps after 永 with コン as furigana.

- (erudaa-ricchi) shisha no dai-mahou-tsukai

死者の大魔法使い

(Elder lich) great magic user of the dead.- The name of a class. A lich is an undead sorcerer.

- This example, and the ones below, have a furigana that annotates a whole noun phrase. In particular, shisha no dai-mahou-tsukai contains the no の particle, which is in hiragana, not kanji.

- (oobaaroodo) shi no shihaisha

死の支配者

(Overlord) ruler of death.- shihai suru

支配する

To rule over. To control (a land).

- shihai suru

- meido-fuku wa (jasuthisu) ore no subete!

メイド服は俺の全て!

Maid clothes are (justice) my everything!- A character proclaims his love for maids, and maid uniforms.

- Likely from the sense of "cute is justice," and "you are my everything," except maid is justice, and maids are my everything.

- (enu-pii-shii) non pureyaa kyarakutaa

Non Player Character

In a game, a character a player controls is a player character, while a NPC is any character that no player controls, like shop-keepers, quest-givers, monsters, and so on.- This isn't a reading aid. A reading aid would be non pureyaa kyarakutaa ノンプレイヤーキャラクター, the katakanization of "Non Player Character." This isn't even a transliteration, as NPC is in the same Latin script as Non Player Character.

- The reason why NPC is used here is because while readers may be familiar with NPC abbreviation found in games, they may not be familiar with the extension "Non Player Character" that comes from English, so NPC works as a Japanese translation for Non Player Character.

- (keeryukeion) Herumesu-shin no tsue

ヘルメス神の杖

(Caduceus) staff of Hermes.- In Greek mythology, the caduceus is a staff carried by Hermes, so the base text contains the true meaning of the katakanized gikun.

- Note that both Hermes and caduceus are in katakana, so this furigana usage can't even be mistaken for a transliteration.

- (makuro wo kumu) jidou-ka shori suru

自動化処理する

(To program a macro) to take care of [it] automatically.- In programming, a macro is a single command that instructs a computer to execute a sequence of commands.

- In this example, the base text explains what the gikun means: programming a macro means making a computer (an NPC in this case) execute a sequence of commands without you having to tell it each and every command every time. In particular, this could be a macro executed in response to something else.

- (poppu su~) jidou-teki ni waki-de~ru

自動的にわき出る

(To pop) to spawn automatically.- In gaming, the Japanese slang poppu suru POPする means for an enemy (or other character) to appear (spawn) in an area. The base text is explaining what this slang means.

Abbreviations

The gikun may contain the meaning of an abbreviation used in the main text.

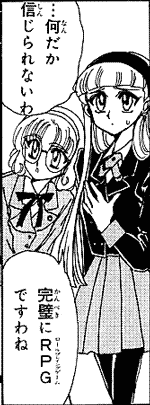

- Context: three girls are told that they were summoned to another world because the princess wished for someone to save the world, so if they save the world the wish will be fulfilled and they'll be able to return to their former world.

- ...nandaka shinjirarenai wa

・・・何だか信じられないわ

... [I] sort of can't believe [it]. - {kanzen ni} (rooru pureingu geemu) aaru-pii-jii desu wa ne

完全にRPGですわね

[It] is {completely} a (role-playing game) RPG, isn't it?

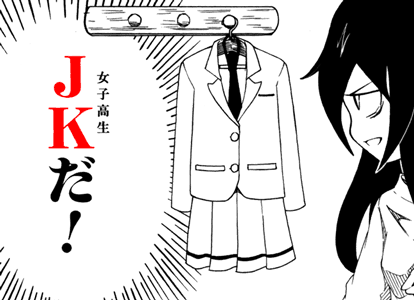

- Context: Tomoko, a middle school girl, talks about what she's about to become.

- (joshi kousei) jeikei da!

JKだ!

[I'll] be a high school girl!- JK, normally pronounced jeikei ジェイケイ, is usually the abbreviation of joshi kousei 女子高生, "high school girl" in Japanese.

Sometimes, an English term is abbreviated in the base text and the furigana contains the katakanization of its expansion. This wouldn't be a gikun, since there are no two ways to read it.

- Context: characters are asked what's their favorite hero, Mineta Minoru 峰田実 answers:

- oira wa Mt. (maunto) Redhi!!

オイラはMt.レディ!!

For me, [it's] (Mount) Mt. Lady!! (correct.)

- Context: Jahy-sama works as a waitress.

- oneechan, kocchi mo nama-chuu futatsu ne

おねーちゃん こっちも生中2つね

Missy, two beers here, too.- nama-chuu - from nama-biiru 生ビール, "raw beer," as in "draft beer," in a a jug of "medium," chuu 中, size.

- oneechan - literally "older sister," also a casual way to refer to a young woman, "missy."

- gaya gaya

ガヤガヤ

*noisy crowd.* - oneechan!? ki-yasuku yobi-otte! ware wo dare da to omotte-iru

おねーちゃん!?気やすく呼びおって!我を誰だとおもっている

Missy?! Calling [me] so casually! Who does [he] think I am?- ki-yasui - relaxed, familiar, casual, as opposed to formal.

- yobi-otte - te-form of yobi-oru 呼びおる.

- ~oru suffixed to the ren'youkei 連用形 of a verb works similarly to ~yagaru ~やがる, used to say someone "dares" to do something to you, expressing angers or amazement.

- nama-chuu futatsu na

生中2つな

Two beers, right? - pi, pi

ピピ

*writing down.* - ware wa makai No. 2 (nanbaa tsuu) no Jahii-sa...

我は魔界No.2のジャヒーさ・・・

I['m] the demon world's number two, Jahy-sa...

- Here, Jahy was about to call herself Jahy-sama. You don't normally use honorific suffixes toward yourself, specially the respectful ~sama ~様, as it sounds pompous. This is typically done by characters that are extremely proud, over-confident, or bossy.

- nanbaa tsuu, the katakanization of "number two," was used as furigana for its abbreviation.

- neechan, kocchi mo~

ねーちゃんこっちもー

Missy, here too~ - a'!? hai!

あっ!?はい!

Ah? [One second]!- hai - "yes," used as an affirmative response in general.

Contextual Aliases

The gikun and the main text may contain different words that refer to the same thing, in which case the gikun is what the character says out loud, while the main text is what the character really means by it.

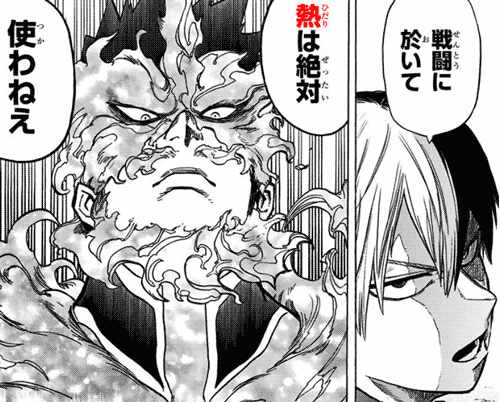

- Context: Todoroki Shouto 轟焦凍 has both cold and heat abilities, which come from the sides of his body: from the right comes cold, from the left comes heat.

- sentou ni oite

netsu (hidari) wa zettai

tsukawanee

戦闘に於いて熱(ひだり)は絶対使わねえ

In battle [I] absolutely won't use heat (left).- In other words: he said he won't use "heat," netsu 熱, by saying he won't use the "left" side, hidari 左.

The word ko 子, literally "child," is also a diminutive way to refer to a "person," hito 人.It's often spelled with the kanji for musume 娘, "daughter," "girl," when the ko 子 you're referring to is female.

- oyako

親子

Parent and child. - oyako

母娘

Mother and daughter.

This ko reading seems to be officially recognized by kanji dictionaries, so it likely wouldn't be considered a gikun.

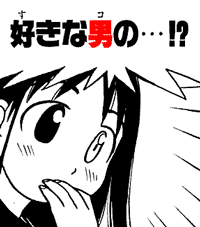

- Context: Harima Kenji 播磨拳児 is full of regret.

- chikushou......!!

ちくしょう・・・・・・!!

[Damn it]......!! - {{{suki na} ko to umi ni ikeru} chansu da} tte no ni yo!!

好きな娘と海に行けるチャンスだってのによ!!

Even though {[it]'s chance [for] {[me] to be able to go to the beach with the girl [that] {[I] like}}}!!- da tte no ni - contraction of da to iu no ni だというのに.

- umi

海

The sea. (literally.)

The beach. (where you go in English.)

On the other hand, using other kanji is still gikun.

Deictic pronouns

The gikun alias may be a demonstrative pronoun like "here," "there," "that," "this," or even a personal pronoun like "I," "him," and so on.

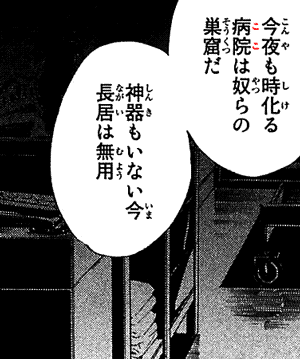

- Context: Yato 夜ト, who is a God fighting spiritual beings related to human's negative feelings, goes to the hospital make a visit to someone, and says:

- kon'ya mo shikeru

今夜も時化る

Tonight, too, will be stormy.- shikeru - for a sea to be stormy. The series is based on Buddhism, using terms like shigan 此岸, literally "this shore," and higan 彼岸, literally "that shore," refer to "this world (of the living)" and "that world (of the dead)," respectively. Consequently, saying "the sea will be stormy" implies those from that world will come to this world in a more chaotic manner.

- (koko) byouin wa yatsura no soukutsu da

病院は奴らの巣窟だ

(This place) the hospital is their lair.- koko ここ, "here," "this place" is used as reading for byouin 病院, "hospital," because "here" is "the hospital," that's where the character was when he said that.

- {shinki mo inai} ima nagai wa muyou

神器もいない今長居は無用

Now [while] {[I] don't have a regalia}, a long-stay is unnecessary.- shinki 神器, literally "divine instrument," also translated to "regalia" in English, refers weapons to fight spiritual beings. Since these weapons are actually other characters that transform into weapons, and not just objects, the animate existence verb iru 居る was used instead of the inanimate aru 在る.

- The temporal noun ima 今, "now," is qualified by a relative clause in this sentence.

- Context: vikings viking around.

- {hajime wa are datta} kedo Ingurando (kocchi) no biiru nimo chikagoro narete-kita yo na

はじめはアレだったけどイングランドのビールにもにも近頃なれてきたよな

{At first [it] was "that"} but lately [I feel like] [I] have gotten used to (this side) England's beer.- are アレ, "that," can also mean something feels weird, or not right, in this case, that the beer felt weird, but lately he's gotten used to its taste.

- kocchi こっち, "this side," is used as gikun for England in this panel because the vikings aren't from around England, i.e. their country is "over there," acchi あっち, and to "this direction," "this side," "around here," kocchi こっち, is England.

- a! ii na, ore nimo hitokuchi

あ!いいな オレにもひとくち

Ah! [That] is nice. Give a sip to me, too.

- Fantomuhaibu-ke toushu wa

ファントムハイブ家 当主は

The head of the Phantomhive family... - ”Shieru-Fantomuhaibu (kono boku)*” da

”シエル・ファントムハイブ(この僕)”だ

is "Ciel Phantomhive (this me)*."- See kono ore da この俺だ for other examples of "this me" being used in Japanese.

Definition

According to dictionaries, gikun 義訓 means:

- To associate a word with a kanji based on the kanji's meaning.

- kanji kango no igi ni yotte kun wo ateru mono

漢字漢語の意義によって訓を当てるもの(デジタル大辞泉:義訓)

Assigning a kun'yomi according to the kanji's Chinese word meaning. - Examples include haru 暖, "spring" and fuyu 寒, "winter," spelled with the kanji for "warm" and "cold," respectively.

- kanji kango no igi ni yotte kun wo ateru mono

- To associate a word with a non-standard reading.

- kanji ni kotei shita ippan-teki na kun dewanaku, sono kanji mata wa kanji-renzoku ga bunmyaku-jou imi suru tokoro wo kun toshite ateta mono

漢字に固定した一般的な訓ではなく、その漢字または漢字連続が文脈上意味するところを訓として当てたもの(日本国語大辞典:義訓)

Assigning not the general (as in normal) kun'yomi that's fixed to a kanji, but the meaning of that kanji's or kanji sequence's in that context as a kun'yomi. - "oya" wo "oya" to yomu no wa kotei shita ippan-teki na kun de aru no ni taishite, [...] "fubo" wo "oya" to yomu you na baai.

「親」を「おや」と読むのは固定した一般的な訓であるのに対して、「父母」を「おや」と読むような場合

Reading 親 as おや is a fixed, general reading, compared to that [...] [gikun refers to] cases like reading 父母 as おや.

- kanji ni kotei shita ippan-teki na kun dewanaku, sono kanji mata wa kanji-renzoku ga bunmyaku-jou imi suru tokoro wo kun toshite ateta mono

Although the wording is different, it seems pretty clear from the examples that both dictionaries are talking about the same thing, but that needs a bit of explanation.

First, the kanji are Chinese characters that Japan loaned from China long, long ago. These characters were pronounced in a certain way in Chinese, and that way was loaned into Japanese, too, as some of the kanji's readings.

The Chinese characters are called "hanzi" in Chinese. Written 漢字. In Japanese, the word kanji 漢字, literally "Chinese characters," is written with the same characters, but pronounced a bit differently.

This slightly different pronunciation based on the Chinese pronunciation is called on'yomi 音読み, literally "on readings," like kan being an on'yomi of 漢. A non-Chinese reading is called a kun'yomi 訓読み.

When the kanji were loaned, you had Japanese words, and Chinese characters, but you didn't write Japanese words with Chinese characters yet. When Japanese words started being written with Chinese characters, their pronunciation became the kun'yomi of the characters selected to spell them.

The kanji weren't associated randomly. If a Japanese word means "to eat," for example, it gets a kanji whose meaning is related to eating, and that kanji has such meaning, most likely, because in Chinese the word it spells is related to eating.

As such, taberu 食べる means "to eat," and shokuji 食事 means "meal," and even though one is kun'yomi and the other is on'yomi, the meaning of the words is in a sense related.

The gikun isn't a Chinese reading, so it's not an on'yomi, it's a kun'yomi, that's why it's called a gikun in first place.

Literally, gikun means "artificial kun," in the sense of "artificial reading." I've seen some texts say it literally means "meaning reading" or something "meaning"-related, but I don't think it means that.

That's because this gi~ 義~ morpheme is used in various words to mean "something that doesn't naturally belong to something else, but was made belong artificially." For example:

- gibo

義母

Foster mother.

- Not a biological mother, an adopted mother. She wasn't originally your mother, until she was.

- gigan

義眼

Prosthetic eye.

- Not a biological eye, an artificial eye. It wasn't your eye, until it was.

In the same sense, a gikun isn't a natural, intrinsic, standard reading. It's not the reading that's "fixed" on a kanji. It's a reading that's added artificially, and wouldn't normally belong to it. A prosthetic reading, an adopted reading, an artificial reading.

Awkwardly, gikun, being a kun'yomi, is a reading of a kanji, so it's only TECHNICALLY called gikun if the furigana on a kanji isn't one of its standard readings.

If the base text contains non-kanji characters, that wouldn't be a gikun. For example:

- (oobaaroodo) shi no shihaisha

死の支配者

(Overlord) ruler of death.

Above, the base text (死の支配者) contains no の, a hiragana, so 死の支配者 isn't a kanji or a kanji sequence, it's just a random phrase, and the furigana isn't a reading of a kanji, it's just another random phrase.

In fact, although a reading aid would normally be in hiragana, and even the word furigana ends in ~gana, the creative use of the furigana has no such limitation. You can write ANY PHRASE to annotate ANY OTHER PHRASE.

It can be kanji in the furigana, letters in the furigana, furigana for symbols, etc. There are no rules, except for the idea that the furigana ALWAYS shows how you're supposed to read the text.

- (kuuhaku) 「 」, "(blank)" never loses.

- In No Game No Life ノーゲーム・ノーライフ, siblings Sora 空 and Shiro 白 use a literal blank space as in-game name when playing together, because the kanji of their names combined forms the word kuuhaku 空白, "blank space."

- The base text is " ", literally, quotes included, as 「」 are quotation marks in Japanese.

Cases like the above aren't exactly gikun, or even exactly furigana. In principle, they're the same, but technically, if you go by the definition on the dictionary, they are not.

Since we're not really concerned with the strict definition of gikun, let's talk about principles.

At first glance, the furigana can be used in two different ways:

- To show how to read a word.

- To show something else.

We call the first a "reading aid," and the second a gikun, but there is a problem.

The furigana ALWAYS shows how to read a word or phrase, even when it's a gikun. In the examples above, 死の支配者 is read oobaaroodo オーバーロード because the furigana says so, thus we need to a different dichotomy.

- A reading aid is when the ruby text and base text mean the same thing.

- A gikun is when the ruby text and the base text mean different things.

But that's wrong, too, because just like "overlord" means "ruler of death" in the series' context, the word blank space means a literal blank space. Neither dichotomies above correctly divide what this article about.

It's obvious that gikun isn't a reading aid, so we need a better definition of a reading aid to understand what is a gikun.

A reading aid doesn't simply show how to read a word in a context. We assume a word is always written the same way regardless of context, so the real purpose of a reading aid is to teach you how to read that word regardless of context.

But the word is going to be written in text, and the reading aid, too, will be written in text. How do you teach someone to read a text using another text? If they knew how to read text, they wouldn't need the text to teach them how to read text!

As we already know, Japanese has multiple scripts: the kanji, hiragana, and katakana. Normally, the reading aid uses hiragana to teach how to read kanji. In other words, the reading aid doesn't use text to show how to read text, it uses one script to show how to read another.

Writing a text that was in one script using another script, such as converting kanji to hiragana, is called transliteration. We can define our dichotomy as:

- A reading aid is when the ruby text is a transliteration.

- A gikun is when the ruby text is NOT a transliteration.

A transliteration is only necessary for an audience that can't read the original script, that's why manga for children, for example, is full of furigana, but manga for older audiences is not.

Thus, if you remove all the furigana and nothing of value is lost, that's because those were just transliterations, just reading aids.

- 死 and shi 死 are equivalent for someone who knows how to read 死. Adding or removing the reading aids changes nothing.if you know how to read the word already.

If you remove the furigana from "overlord," you lose the information that the game uses a bunch of English words to call its classes, items, and so on.

- 死の支配者

If you remove the furigana from Kuuhaku, you lose how the character's pseudonym is stylized in text, and perhaps even that "blank" is supposed to be read out loud.

- 「 」 never loses.

These can't be mere reading aids then, these are clearly gikun.

On the other hand, katakanizations are mere reading aids, since they're transliterations. More specifically, foreign words loaned into English are normally spelled with katakana, and they tend to sound different due to the Japanese language having fewer sounds.

For example, Japanese doesn't have an L, so any English word with L gets katakanized with r~ syllables.

- za waarudo

The World

The katakanization in the furigana above is only necessary for an audience that can't read the foreign word in Japanese in its original Latin script. The word "world" is always katakanized the same way, so the reading aid can teach you its katakanization.

Another example of transliteration you may find is romanization, a.k.a. the romaji ローマ字, "Roman characters," which is when we transliterate something to the Latin (Roman) script.

- Context: the staff card of an OL character, showing her name with furigana in romaji.

- gurafikkaa

グラフィッカー

"Graphic-er." (wasei-eigo 和製英語.)

Graphic artist. - Suzukaze Aoba

涼風青葉

It doesn't make sense to call the example above gikun. After all, 涼風青葉 is Suzukaze Aoba regardless of context.

Sometimes, the furigana shows how to pronounce the name of a symbol, assuming it should be pronounced out loud in a text, which would make it akin to transliteration. The following examples are NOT gikun:

- batsu ×, the "X" mark. When used as a multiplication symbol, it's read kakeru × instead.

- manji 卍, "swastika." The English term swastika refers to the 卍 shape, which is called manji in Japanese, but technically 卍 can be used in text as a Chinese character, making it a kanji, rather than a symbol.

- Some symbols don't have their names read out loud, but are part of words, such as the iteration marks (々ゝヽ), which repeat the preceding character, and the small ke ヶ-shaped symbol, which is typically read as ga が, e.g. hitobito 人々, "people," Senjougahara 戦場ヶ原, a surname.

Sorta Standard Gikun

Unfortunately, gikun may be way more complicated than it seems, when you consider that it relies on the idea of there being standard spellings and non-standard ones, and standards change.

By calling something a gikun we're saying that, normally, the word in the furigana wouldn't be spelled with those kanji, which means you're spelling the word wrong.

We're saying that if you removed the furigana, the reader wouldn't read it the same way anymore, because it's not supposed to be read the way the author intends.

If you remove oobaaroodo オーバーロード from 死の支配者, people would read it as shi no shihaisha. Nobody would think "overlord" is spelled 死の支配者. That makes no sense.

However, if we time-traveled to the past, before native Japanese words started being spelled with kanji, the kun'yomi wouldn't exist yet, so spelling taberu with kanji, as 食べる, wouldn't be a standard spelling, it would be a gikun.

Similarly, it's entirely possible for some word-kanji associations to be considered a gikun today, but that would be a standard spelling tomorrow.

However, for some reason this doesn't seem to occur with loan-words spelled with kanji.

Standard Kanji for Loan Words

Words like "tobacco" and "coffee" have somewhat standard kanji spellings—they can even found in the dictionary—but, because they're loan words, they aren't considered "standard" readings of the kanji.

- koohii 珈琲, "coffee."

This doesn't apply to all loan words. Chinese loan-words are originally spelled with kanji in China, so when they're loaned into Japanese, the katakanization of the Chinese word may get spelled with the same kanji as the original Chinese word, making the furigana a transliteration.

- maajan 麻雀, "mahjong (board game)."

The wasei-eigo (Japanese word made out of English) and wasei-gairaigo 和製外来語 (English loan word with an unique meaning in Japanese) are considered English words as far as gikun is concerned, even though neither are actually English.

For example, the slang yankii ヤンキー, from English "yankee," is often spelled as furyou 不良, "delinquent," because that's what it means in Japanese, even though "yankee" doesn't mean "delinquent" in English. Despite this original Japanese sense, such spelling is still considered a gikun.

- Context: a guy leaves the hospital after being hospitalized after a street fight. A nurse gives him advice.

- ii-kagen (yankii) furyou nante yamete majime ni yarinasai

いいかげん不良なんてヤメてマジメにやりなさい

For crying out loud, stop being a delinquent and do it seriously. - dakara (yankii) furyou janai ttsuu no

だから不良じゃないっつーの

[Like I said already], I'm not a delinquent.

- ttsuu no - contraction of to itte-iru no と言っているの.

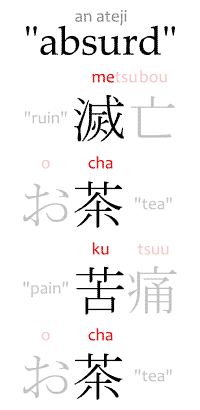

Note that there is a way to spell a word with kanji without it becoming a gikun: the phonetic ateji 当て字, which is when you select kanji by readings the kanji already have and disregard their meanings to spell a word, like mechakucha 滅茶苦茶.

You could say that the gikun that selects kanji to spell a random word by the meaning of the kanji is a semantic ateji by comparison.

Non-Standard Pronunciation

If a word is pronounced in a non-standard way, its furigana may differ from the standard in order to reflect that. At first glance, this is clearly a case of gikun. However, many of these "non-standard" pronunciations follow a well-defined pattern that makes them practically standard readings.

For example, in relaxed pronunciation, i-adjectives that end in ~oi, like tsuyoi 強い, "strong," are instead pronounced ending in ~ee , like tsuee 強ぇ.

Observe that the okurigana 送り仮名 changes from ~i ~い to ~e ~ぇ.The same applies to:

- sugoi 凄い, "amazing."

- sugee 凄ぇ, same meaning, relaxed pronunciation.

These are both reading aids. You learn that 凄い is read すごい by the furigana. In any text where 凄い is written, regardless of context, it's going to be read すごい. Similarly, you learn 凄ぇ is read すげぇ by the furigana.

It doesn't seem to make much sense to say すげぇ is gikun if it serves the same purpose as すごい just because it's a relaxed pronunciation.

One possible counterargument is that the okurigana is technically part of the kanji reading. That is, the reading of the 凄 kanji isn't sugo~, but sugoi as a whole. This can be observed in how words in the ren'youkei 連用形 may lose their okurigana:

- hanashi 話, "talk,," "story" instead of hana-shi 話し, ren'youkei of hanasu 話す, "to talk."

- hikari 光, "light," instead of hakari 光り, from hikaru 光る, "to shine."

- arigatou 有難う, "thanks," instead of arigatou 有り難う, from aru 有る, "to have," and ~gatai ~がたい, "difficult to," affected by u-onbin.

If you remove the okruigana, 凄い and 凄ぇ both become just 凄, and then すごい is a standard reading for this kanji, but すげぇ wouldn't be.

Note that this also occurs with other adjectives, like ~ai ~aい to ~ee ~eえ.

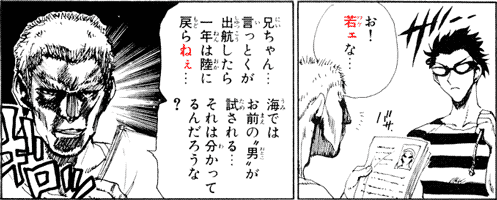

- Context: Harima Kenji 播磨拳児 goes join a ship crew to sail the seas.

- o! wakee na...

お!若ェな・・・

Ooh! Young, [aren't you]...

- wakai

若い

Young.

- wakai

- niichan... ittoku ga shukkou shitara ichinen wa oka ni modoranee...

兄ちゃん・・・言っとくが出航したら一年は陸に戻らねぇ・・・

Kiddo... [let me warn you], after [we] set sail, [we] won't be back shore in [at least] one year.- niichan - "older brother," also refers to a "young man."

- ~toku ~とく - contraction of ~te-oku ~ておく.

- umi dewa omae no "otoko" ga tamesareru...

海ではお前の“男”が試される・・・

In the sea, your "man" will be tested...

- In the sense of how much of a man he is, i.e. if he's man enough to brave the seas, or if he'll chicken out.

- See also: otoko 漢, quotation marks.

- sore wa wakatteru-n-darou na?

それは分かってるんだろうな?

[You] understand that, [right]?- ~teru - contraction of ~te-iru ~ている.

- giro'

ギロッ

*glare*

References

- 義訓 - 日本国語大辞典 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2021-08-17.

- 義訓 - デジタル大辞泉 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2021-08-17.

Just wanted to say that this was a really well-put together article and did a good job of explaining something I had been curious about even since I first noticed it pop up in a manga panel. Thanks for posting this!!

ReplyDeleteAnd here I am, who's been too lazy to check whether dots mean something or is it my visual novel to blame. Always thought that the developers just made a mistake.

ReplyDelete