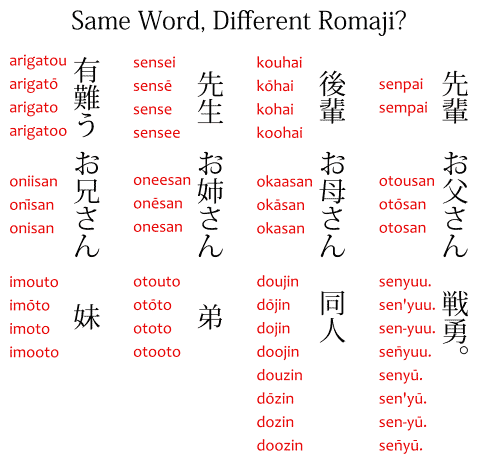

Every now and then you see a single same word with multiple, different romaji. Specially containing letters with macrons, like āēīōūn̄.

For example, arigato, arigatō and arigatou. Or kohai, kōhai, and kouhai. Or senpai and sempai. Or on'yomi and onyomi. Or "monster" being monsutaa, monsutā or left as literally monster in romaji.

After all, what's the correct romaji for these words? And why does this even happen?

- Which Romaji Is Correct?

- English Words in Romaji

- Aa / ā / a

- Ei / ē / e / ee

- Ii / ī / i

- Ou / ō / o / oo

- Uu / ū / u

- N / m

- N / n- / n' / n̄

- Hyphens

- Ha / wa, he / e, wo / o

- Fu / Hu

- Sho / Syo

- Chi / Ti

- Long Vowels

Which One Is Correct?

If you're wondering which one is correct, arigatou, arigatō, arigato or arigatoo, the answer is: all of them. And they are all pronounced the same way.

This is because all the romaji above refer to the same word: 有難う.

If 有難う is pronounced one way, and arigatō and arigatou are simply a different way of writing 有難う, then arigatō and arigatou must be pronounced the same way as 有難う. They are all pronounced the same.

But if they are all pronounced the same, why is the romaji different?

Why Romaji Varies

Basically, transliteration isn't an exact science. There's no official romanization for a given word. Because the romaji changes depending on the method applied to obtain that romaji.

For example, some methods are based simply on the letters. The same letters result in the same romaji. It's consistent that way. However, if two words written the same are pronounced differently in Japanese, that won't show in the romaji.

So there are also methods which attempt to transcribe how the word is pronounced. Here you already have a difference. A single word may be romanized based on how it's written or on how it's pronounced. And since you're just writing down the sounds you're hearing, two different people may end up romanizing the same word differently based on what they think it sounds like.

Why Romaji Doesn't Vary, Sorta

To make sure the romaji stays consistent from person to person, certain rules were created to romanize words. A set of such rules is called a romaji system.

One romaji systems or another and their rules are used as reference pretty much every time a word needs to be romanized. That's why, most of the time, a single word Japanese word is only ever romanized in one way.

But then there are differences between the systems. There are even differences within a same system, because its rules were updated and some people still follow the old version.

And then new differences are born purely from the fact that some people are using a system but they don't know or can't be arsed to follow all of its rules, so they adopt some rules but skip over others, creating a romaji different from that of a person who followed all the romaji rules.

Below I'll list some of the common variations of romaji found in words and where they come from. I hope it serves as reference and answers the "why a single word has two romaji?" question.

English Words in Romaji

Sometimes, when the Japanese phrase contains a word that's a katakanization, that is, a loaned word that's normally written with katakana, the original English word that the katakanization is based on might get written in the romaji.

One example of katakanization is found in the name of the Japanese game pokémon, which comes from English words:

- poketto monsutaa

ポケットモンスター

Pocket monster.

But that isn't a really good example because the whole phrase is in English. A better example would be when it mixes loaned words and native words:

- monsutaa musume

モンスター娘

Monster girl.

The term above combines monsutaa, the katakanization of the English word "monster," with musume 娘, a Japanese word that can mean "daughter" or "girl." The term can also be romanized as:

- monster musume

モンスター娘

The above happens even though, normally, the romaji of Japanese words never contains "st" or ends with "r." Likewise:

- Tensei shitara Suraimu Datta Ken

Tensei shitara Slime Datta Ken

転生したらスライムだった件

"The case [in which] after reincarnating [I] was a slime."

The Japanese language doesn't have an "L" consonant, so "slime" is katakanized to suraimu, with an R. But the romanization may feature the original English word: slime, which oddly does have an L and stands out like a sore thumb in the romanization.

Aa / ā / a

The romaji aa, ā, and a are for long vowels starting with a, like ああ and あー.

See the Long Vowels section below for explanation.

Examples:

- お母さん

おかあさん

おかーさん

okaasan

okāsan

okasan - お祖母さん

おばあさん

おばーさん

obaasan

obāsan

obasan - 麻雀

マージャン

maajan

mājan

majan

Ei / ē / e / ee

The romaji ei is for えい, which may be a long vowel.

The romaji ē, e, and ee are for long vowels starting with e, like えい, えー and ええ.

See the Long Vowels section below for explanation.

Examples

Ii / ī / i

The romaji ii, ī, and i are for long vowels starting with i, like いい and いー.

See the Long Vowels section below for explanation.

Examples

- お兄さん

おにいさん

おにーさん

oniisan

onīsan

onisan - ヒーロー

hiiroo

hīrō

hiro

Ou / ō / o / oo

The romaji ou is for おう, which may be a long vowel.

The romaji ō, o, and oo are for long vowels starting with o, like おう, おー, and おお.

See the Long Vowels section below for explanation.

Examples

- 有難う

ありがとう

arigatou

arigatō

arigato

arigatoo - 今日

きょう

kyou

kyō

kyo

kyoo - ローマ字

ローマじ

roumaji

rōmaji

romaji

roomaji - 氷

こおり

koori

kōri

kori

- 後輩

こうはい

kouhai

kōhai

kouhai

koohai - 同人

doujin

dōjin

dojin

doojin - 東京

とうきょう

toukyou

tōkyo

tokyo

tookyoo - 東方 仗助

ひがしかた じょうすけ

Higashikata Jousuke

Higashikata Jōsuke

Higashikata Josuke

Uu / ū / u

The romaji uu, ū, and u are for long vowels starting with u, like うう and うー.

See the Long Vowels section below for explanation.

Examples

- 九尾

きゅうび

kyuubi

kyūbi

kyubi - キュゥべえ

kyuubee

kyūbe

kyube

("Kyubey," from Madoka Magica) - 十二大戦

じゅうにたいせん

juuni taisen

jūni taisen

juni taisen

N / m

In traditional Hepburn, n ん is romanized as m ん if it comes before a b, m, or p syllable.

Modified Hepburn, more recent, does not have this rule.

Examples

- 先輩

せんぱい

senpai

sempai - 貧乏

びんぼう

binbou

bimbou - binbō

- bimbō

- 段ボール

だんボール

danbooru

dambooru

danbōru

dambōru - 乱麻½

らんま½

ranma 1/2

ramma 1/2

N / n- / n' / n̄

In Hepburn, the syllabic n ん is romanized n ん. However, to make sure n ん + a あ, two syllables, wouldn't look like a single na な syllable, the n ん is romanized differently if it comes before a vowel or an y-syllable.

In traditional Hepburn, it becomes n-, with a dash. In modified Hepburn, it becomes n', with an apostrophe.

Because not everybody is aware of this rule, people may end up transliterating kon'ya or kon-ya 今夜 as konya 今夜 instead, which looks like ko-nya こにゃ even though it is ko-n-ya こんや.

In JSL, it's always romanized n̄ ん with a macron, because they didn't want to deal with these shenanigans.

Examples

- 戦勇

せんゆう

sen'yuu

sen-yuu

senyuu

sen̄yuu

sen'yū

sen-yū

senyū

sen̄yū

Hyphens

Sometimes honorific suffixes like sama, san, and chan are added to nouns, and when romanized they're separated by a hyphen. Sometimes, they are not separated by a hyphen.

Likewise, other suffixes in general like pluralizing suffixes, etc. can get treated with the hyphen or lack of thereof.

Furthermore, in some cases the suffix is a noun, so it becomes hard to figure out if it's a noun plus suffix or an adjective-noun plus noun. In such cases, an hyphenated version and a space-separated version end up existing.

Nobody is really sure when to put the hyphen.

Examples

- お母さん

おかあさん

okaasan

okaa-san - 僕達

ぼくたち

bokutachi

boku-tachi - 六本木駅

ろっぽんぎえき

roppongi-eki

roppongi eki

Ha / wa, he / e, wo / o

The kana ha-he-wo はへを are sometimes romanized as wa-e-o はへを.

This only happens when the kana represents a grammar particle. For example:

- haha wa hantaa はは は はんたー

Mother is a hunter. - henshin e no enerugii へんしん へ の エネルギー

The energy [used] toward the transformation.

And it only happens with the particles because the particles are pronounced differently like that. And the reason for that has been explained in another post: Why is ha は wa?

Fu / Hu

In the Hepburn romaji system, it's romanized fu ふ. In Nihon-shiki and Kunrei-shiki, the romanization is hu ふ.

Examples

- 風船

ふうせん

fuusen

huusen

fūsen

hūsen

Sho / Syo

In Hepburn and similar romaji systems, sho しょis romanized as sho, mimicking the pronunciation.

In Nihon-shiki and Kunrei-shiki systems, sho しょ is romanized as syo, because those systems prefer to be regular (kyo, myo, syo instead of sho).

Examples

- 少年

しょうねん

shounen

shōnen

syounen

syōnen - 少女

しょうじょ

shoujo

syouzyo

shōjo

syōzyo

Chi / Ti

In Hepburn, it's chi ち, in Nihon and Kunrei-shiki, it's romanized ti ち.

Examples

- 地球

ちきゅう

chikyuu

tikyuu

chikyū

tikyū

Long Vowels

A common way in which romaji varies is in how a romaji system transliterates long vowels.

In Japanese, a long vowel happens when the vowel part of a syllable takes longer than one mora of time to pronounce.

To elaborate:

- ko

こ

One syllable. One mora. - koe

こえ

Two syllables. Two mora. - koo

こー

One syllable. Two mora. - koo

こお

One syllable. Two mora.

Basically, instead of pronouncing ko and o separately, the sound of the first syllable is dragged for a bit longer.

The long vowels don't only happen when you have the same vowel repeated. For example, ou おう may be pronounced as a long o. And ei えい may be pronounced as a long e.

Compound kana may have long vowels too. For example: kyuu きゅう is a kyu ending in a long u.

Generally speaking, (there are some exceptions), long vowels only happen within morpheme boundaries. This means that meiro 迷路, "labyrinth," has a me with a long e, because mei 迷 is a single morpheme. However, meiro 目色, "eye color," is pronounced differently, with me 目, "eye," and iro 色, "color," pronounced separately.

Ignore It

The most simple approach to transliterating long vowels is to just ignore them.

So o お and u う is always ou おう, no matter what it's pronounced like.

Macrons

A common approach to transliterating long vowels is to add a macron to the long vowel and remove the extra vowel. For example:

- gakkou

gakkō

学校

School.

Forget The Macron

Most people don't know how to type a macaroon, much less a macaroni, or a macron. So if they see kyōto written somewhere, they might try to copy it, but they won't be able to type the macron, and type it just as Kyoto.

- kyouto

kyōto

京都

Kyoto.

Doubled Vowels

Another approach (used by the JSL romaji system, for example), is to double the long vowel, but remove the second vowel. It's like doing the macron, but removing the macron and repeating the vowel. Example:

- kouhai

kōhai (add macron, remove u)

kohai (forget the macron)

koohai (double the vowel)

後輩

Discrepancies

It's interesting to note that the approaches toward long vowels vary from system to system.

For example, modified Hepburn says you can't macronize sensei 先生, even though it's a long vowel. Hepburn doesn't macronize ei えい syllables. It only macaronizes ē えー syllables, written with a prolonged sound mark ー.

However, the book Genki does think sensē 先生 should be macaronized... except it doesn't macaronize stuff. Instead, it uses double vowels. So, in the book, it's romanized sensee 先生, with a doubled e.

This burogu is just sugoi! As a self-respecting weeaboo, I love stuff like this.

ReplyDeleteKeep up the great work :D