Source: japanesewithanime.com (CC BY-SA 4.0)

- anime ga suki da

アニメが好きだ

Anime is liked. (literally.)

[I] like anime.

In this article, I'm going to explain how this Japanese "alphabet" works, that is: how are words written in Japanese and how to read Japanese.

Hiragana, Katakana and Kanji (and Romaji)

To begin with, let's see how you write the words for each of the three "alphabets" in Japanese.- ひらがな

- カタカナ

- 漢字

Can you read that? No? Okay, let's add some "Roman characters," romaji ローマ字, then:

- hi-ra-ga-na

ひらがな - ka-ta-ka-na

カタカナ - ka-n, ji

漢字

Okay, now you can read it. But you're reading it wrong. I don't know how you're reading it, but if you read the hi ひ of hiragana like "hi, how are you?" You read it wrong.

Romanization

The romaji won't tell you how to pronounce the words right. It's simply a standard way of writing the Japanese "alphabet" using Latin alphabet characters. A process called transliteration, or romanization in this case.To have an idea, the English word "ice" loaned into Japanese becomes aisu アイス. This is a katakanization. Similarly, the word "the world" becomes za waarudo ザ・ワールド. The L becomes R because there's no L in the Japanese alphabet, hence the Engrish.

Further, there are different romaji systems that will romanize the same Japanese word in different ways using different rules. Because why not? It's not like you know Japanese enough to read them right anyway.

- senpai 先輩

se-n, pa-i せんぱい

sempai (with an m)

Senior. - doujinshi 同人誌

do-u, ji-n, shi どうじんし

dōjinshi (with a macron.)

douzinsi (because in the Hepburn system it's sa-shi-su-se-so さしすせそ and za-ji-zu-ze-zo ざじずぜぞ, and the Nihon-shiki system thinks that's just wrong and it should be sa-si-su-se-so and za-zi-zu-ze-zo.)

A fanzine. Literally: publication of someone equal. - Yugioh 遊戯王

Yu-u, gi, o-u ゆうぎおう

Yūgiō. (with macrons.)

King (ou) of Games (yuugi). - Azumanga Daioh あずまんが大王

Great (dai) King (ou) Azumanga.

Nevertheless, not all is bad.

English is a cursed language. "I'll read it tomorrow" and "I read it yesterday" are pronounced differently. In Japanese, the kana always have the same sound no matter what word they're in. Sometimes the accent changes, but the sound is basically still the same.

(except for ha は becoming wa は, he へ becoming e へ, but you get used to it.)

Therefore, if you know how senpai is pronounced, you'll know how se せ, n ん pa ぱ and i い is pronounced no matter the word it's in.

You should be able to read せんせい now, for example, even without romaji.

Kana Chart

The Japanese language contains "50 sounds," gojuon 五十音, that serve as basis for the entire language. That's the five vowels, a-i-u-e-o, plus nine rows of consonants (k-s-t-n-h-m-y-r-w), so (1 + 9) × 5 = 50, except not exactly.Diacritics, like ka か becoming ga が, are tenten or dakuten 濁点, and aren't included in those 50 sounds.

Once you memorize these not-really-50 sounds and you should be able to read anything in Japanese. Kind of.

There are various ways to achieve this. You could get an online kana chart and practice writing it down or paper or something. Or you could memorize it with an online quiz about kana, or download the app Hiragana-chan for android.

A lot of people traditionally learn to handwrite Japanese on paper, but if all you're going to use Japanese for is reading what the voice actor of your waifu posts on twitter, you don't really need to worry about it.

(don't tell anyone you don't know how to handwrite, though, they may judge you harshly for it.)

The point is: you can't learn Japanese with romaji alone. You need to know to read actual Japanese. Don't hate the moonrunes, learn the moonrunes. Otherwise you'll be illiterate. Learning the kana is the first step and probably greatest hurdle to learning Japanese.

Once you learn it, though, it's all downhill from there. I mean, like a snowball effect. You can't stop after that. You can't unlearn Japanese after that.

For reference, below is a romaji chart showing all the kana.

Besides the above, there are some archaic kana like wi ゐ and we ゑ, and stuff like vu ヴ and fa ファ that's only found in loaned words, not in native Japanese words. There are also some special symbols that we'll see later in this article.

Do keep in mind that wo を is pronounced just like o お, but it's romanized and spelled different when it means the wo を particle. There are basically no words spelled with wo を, by the way, except stuff like wotaku ヲタク, so if you see wo を, it's always the particle.

Hiragana vs. Katakana

Just like you can transliterate a word from Japanese into Latin, you can transliterate a word from one Japanese alphabet into another Japanese alphabet. Observe:- hiragana ひらがな / ヒラガナ / 平仮名

- katakana かたかな / カタカナ / 片仮名

- kanji かんじ / カンジ / 漢字

Above, the word "kanji" is spelled with hiragana, as かんじ, with katakana, as カンジ, and with kanji, as 漢字.

With few exceptions, like vu ヴ, any word that can be spelled with hiragana can be spelled with katakana and vice-versa. The same is valid for kanji, except that some words don't have kanji, so they're normally only written with kana.

This is just like you can spell any word with lower-case characters or WITH UPPER-CASE CHARACTERS. Except it's a bit different. The reasons for a word to be spelled different from normal include, for example, the fact that katakana looks cooler than hiragana.

Generally, loan words like "animation" are spelled with katakana (anime アニメ). Simple words are spelled with hiragana. Most nouns are spelled with kanji. A large number of verbs and adjectives mix kanji and hiragana. In order words: all three of them are used all the time.

So if you thought you could ignore learning katakana just because it's the same thing as hiragana, I have bad needs for you: you gotta learn both.

Syllabaries

In English, the Latin alphabet forms syllables by joining letters that represent consonants with letters that represent vowels. For example, "no" is a syllable formed by the consonant "N" plus the vowel "O."In Japanese, each kana represents a whole syllable. The syllable "no" would be just no の.

For this reason, hiragana and katakana are said to be "syllabaries" rather than "alphabets." But it's a bit more complicated than that.

There are six vowels in Japanese: a-i-u-e-o あいうえお, plus the nasal n ん.

This means na-ni-nu-ne-no なにぬねの each has its own kana, since they're each a syllable on its own. You don't form the "na" syllable by spelling the nasal n ん plus a あ.

In fact, there's pretty much no word in Japanese that starts with n ん, but a lot of them end with n ん.

- shi-ri, to-ri しりとり

Or shiritori 尻取り, "butt-taking."

A word game where someone says a word, and you have to say a word that starts with the kana that their word ends with. - ri-n, go りんご

Or ringo 林檎.

Apple. - go, ha-n ごはん

Or gohan 御飯

Cooked rice. Meal. - A shiritori game ends when someone says a word that's been said before, or a word that ends with n ん, because there aren't native Japanese words that start with n ん.

In romaji, an apostrophe should be (but often isn't) used to differentiate the two. Observe:

- gen'in 原因

ge-n, i-n げんいん

Reason. (for something to happen.) - genin 下忍

ge, ni-n げにん

A lower (ge) ni-n, ja 忍者 in Naruto. - Sen'yuu. 戦勇。

A proper way to romanize "Senyuu." The manga and anime.

Although each kana represents a whole syllable on its own, it's not true to say that if you have four kana, you'll have four syllables. That's because you can have a single syllable formed by multiple kana. For example:

- koukou 高校

ko-u, ko-u こうこう

High-school.

Above, we have two syllables: kou and kou again. This is a called a long vowel. The u う has the effect of making ~o get pronounced for longer than usual. So it's just one long ko syllable, not a ko syllable followed by an u syllable.

This is the reason for the macron, kōkō, in some romaji systems. The macron means the o vowel is pronounced for longer than usual.

If you have seen enough anime, you may have noticed that kōkō こうこう, "high-school," takes longer to pronounce than koko ここ, "here," even though it sounds very similar.

Mora

Since ko-u こう is just one syllable but longer than ko こ, we can say the the kana represents "the time it takes to pronounce stuff" rather than just "it represents syllables."An unit of this "time" is called a "mora" of time.

The word koko ここ has two kana, so it takes two mora to pronounce. While koukou こうこう has four kana, so it takes four mora to pronounce. It takes twice as long to pronounce the same thing.

Similarly, ni-n-ge-n 人間, "human," has two syllables but takes four mora to pronounce.

By the way, a haiku 俳句 poem follows a 5-7-5 mora pattern, but people often call it 5-7-5 syllables instead because nobody knows what a "mora" is. A tanka 短歌 poem follows the 5-7-5-7-7 pattern. For reference, below is the tanka most well-known by weebs:

- 5: chi-ha-ya bu-ru

千早振る(ちはやぶる)

Turbulently. - 7: ka-mi-yo mo ki-ka-zu

神代も聞かず(かみよもきかず)

Even in the divine age unheard. - 5: Ta-tsu-ta-ga-wa

竜田川(たつたがわ)

The Tatsuya river. - 7: ka-ra ku-re-na-i ni

唐紅に(からくれなゐに)

To crimson. - 7: mi-zu ku-ku-ru to-wa

水括るとは(みずくくるとは)

The water dyed. - In the anime Chihayafuru, character Kanade interprets this poem as being about love. Generally the crimson-dyed water is interpreted as being red autumn leaves covering the river. Personally, I can't really tell what it's supposed to mean. I'm not good with poems.

Alright, so now we know that one kana = one mora. Perfect.

That's wrong, though.

Some kana, called small kana, for they're small, are used to change a syllable into a diphthong—two vowels, one syllable—without adding a mora of time to its pronunciation.

A kana compound has a big kana and a small kana and still takes just one mora of time.

Observe:

- kyou 今日

kyo-u きょう

Today. - kiyou 器用

ki-yo-u きよう

Skillful.

Above, we have a big yo よ and a small yo ょ. The word for "today," kyou, is pronounced quickly, while kiyou, "skillful," is pronounced slower, since it takes one mora longer.

Most of the small kana you'll see are are ya, yu, yo やゆよ. They're all combined with kana that end in ~i, like ki き, hi ひ, ni に, and so on.

- hyaku 百

hya-ku ひゃく

One hundred. - byakugan 白目

bya-ku, ga-n びゃくがん

White eyes. (literally.) - nya-a にゃあ

Meow.

With some syllables, the Hepburn romanization changes y to h. This happens with chi ち and shi し. The syllable ji じ is also romanized differently.

- ocha 御茶

o-cha おちゃ

Tea.- ta-chi-tsu-te-to (Hepburn.)

- ta-ti-tu-te-to (Nihon-Shiki.)

- otya is the Nihon-Shiki romanization of "tea."

- shoujo 少女

sho-u-jo しょうじょ

Girl.- syouzyo is Nihon-Shiki.

The word for "girl" is spelled with 5 kana, takes 3 mora, and has 2 syllables. Removing 1 mora from it can have serious consequences.

- shojo 処女

sho-jo しょじょ

Virgin.

There are other small kana, but they're mostly used in foreign words because standard Japanese words don't have those diphthongs.

- redei レディ

Lady. (de with a small i) - sofa ソファ

Sofa. (fu with small a)

A last and most confusing small kana to keep in mind is the small tsu っ. Unlike the normal tsu, the small tsu isn't even pronounced tsu. Instead, it creates a geminate consonant, romanized as a double consonant. Practically, the consonant ends up taking two mora to pronounce.

- shitsuke 躾

shi-tsu-ke しつけ

Discipline. Manners. - shikke 湿気

shi-k-ke しっけ

Humidity.

I repeat: the small tsu っ doesn't mean k, it means the syllable after it, ke け, took twice to pronounce its consonant.

- cho-t-to ma-t-te

ちょっと待って

Wait a bit. - hissatsu waza 必殺技

hi-s-sa-tsu wa-za ひっさつわざ

Sure-kill technique.

When it's at the end of sentences, it normally means a glottal stop and is used in exclamatory tone, when a character is angry, for example:

- koitsu こいつ

This guy. (yeah, that guy) - koitsu! こいつ!

This guy! (great guy!) - koitsu'! こいつっ!

THIS BASTARD!!!!!!! (IMMA MURDER YE!)

This should be romanized as '. In practice, it never is. But that's how it should be if it were.

On the other hand, a long dash ー is a prolonged sound mark that makes the vowel of the syllable before it take an extra mora to pronounce.

- oniisan お兄さん

o-ni-i-sa-n おにいさん

o-ni-i-sa-n おにーさん

Older brother.

Normally, this is only used in words spelled with katakana.

- koohii コーヒー

Coffee. - Boku no Hiiroo Akademia

僕のヒーローアカデミア

My Hero Academia.

This mark changes according to the direction Japanese is written. When it's written horizontally, it's a horizontal line, when it's written vertically, like it in manga and light novels, it's a vertical line.

When characters are screaming, sometimes small kana are used to express a very, very, very long syllable. Other times the prolonged sound mark is used. Or a combination of the two.

- e? え?

Eh? - eeeeeee??? えええぇぇぇぇ???

Eeeehhh???

These are also common in contractions, which reduce the mora of words, that is, contract the time it takes to pronounce:

- de wa nai

ではない

Is not. - janai じゃない

(same meaning.) - janee じゃねえ

janee じゃねぇ

janee じゃねー

(same meaning.) - nakute wa なくては

nakucha なくちゃ

If not. - nakereba なければ

nakya なきゃ

If not.

History

The kanji characters were imported from China very long ago. Literally, if romaji is "Roman characters," then kanji is "Chinese characters." At first, Japanese was written exclusively with kanji, and then hiragana and katakana were made from those kanji characters.For example, the Chinese character 呂 is the origin of the katakana ro ロ. The square thing in 呂 is called a radical (or component). See: 品兄名右石古中 all have a square in them.

There's a kanji that's literally just the square: kuchi 口, "mouth." So ro ロ and kuchi 口 look exactly the same.

Even worse, the katakana ni ニ looks AND sounds the same as the kanji for the number "two," ni 二.

Morphology

All these kanji have meanings associated to them from the words they were used to write in China. Basically, in Chinese there was a word for mouth, and it was spelled with 口. That's why the Japanese word kuchi, "mouth," is also spelled with 口, because that kanji means "mouth."You can even guess the meaning of a word from its kanji sometimes.

- deru

出る

To leave. - de-guchi

出口

Leave-mouth? Leave-opening? Oh!

An "exit." - ji 字

Character. Letter. - rōma-ji

ローマ字

Roman characters. Latin characters. - kan-ji

漢字

Chinese characters. - kan 漢

(must mean China, then.)

Unfortunately, it turns out that Japanese and Chinese are actually different languages. So the word for mouth in Japanese isn't the same as the word for mouth in Chinese. Consequently, the way you read 口 in Japanese is different from the way you read it in Chinese.

These different kanji readings are called on'yomi 音読み, the original Chinese reading, and kun'yomi 訓読み, the Japanese reading, or the original Japanese word that was forcibly written with that kanji.

That wouldn't matter if Japan only imported the Chinese character from China. Unfortunately, Japan also imported Chinese words from China.

For example, kanji is read with on'yomi. In Chinese, the characters are called "hanzi." If you ever heard of a certain "Han dynasty," know that that han is spelled han 漢 in Chinese.

Clearly, kanji and hanzi look like different words that only sorta sound similar. That's correct, because one is Japanese and the other is Chinese.

They probably sounded more similar thousands of years ago when Japan imported the hanzi. Today, however, on'yomi and Chinese pronunciation have drifted apart.

Each kanji ends up having one or multiple readings classified into on and kun.

- hi 火

Fire. (kun) - kuchi 口

Mouth. (kun) - ka-kou 火口

Volcanic crater. "Fire-mouth." (on)

You can even end up with words that mean almost the same thing because they have the same kanji, but are read completely differently.

- otoko 男

Man. (kun) - ko 子

Child. (kun) - otoko no ko

男の子

Boy. (kun, generally a child.) - dan-shi

男子

Boy. (on, sometimes not a child.)

Warning: sometimes the kanji meanings don't make sense. For example:

- mechakucha 目茶苦茶

Reckless. - me 目

Eye. - cha 茶

Tea. - ku 苦

Pain. - Tea again.

This is called an ateji 当て字. Basically, there was the word mechakucha, and a bunch of random kanji that could be read like me, cha, ku, and cha again were picked for the word, without caring if the meanings were coherent or not.

The kun'yomi and on'yomi can be derived form different morphemes and end up having similar meanings that are fundamentally different. For example, with hito 人 and jin 人, hito is kun'yomi while jin is on'yomi.

The word hito means person.

- murabito 村人

A villager.- Person from a:

- mura 村

Village.

- koibito 恋人

Lover.- Person whom:

- koi suru 恋する

To love.

- tabibito 旅人

A traveler.- Like Kino キノ, a person who is in a:

- tabi 旅

Travel.

Meanwhile, jin 人 is like the morpheme "-ian" in English.

- itaria-jin イタリア人

Italian. Person from Italy. - amerika-jin アメリカ人

American. Person from America. - uchuujin 宇宙人

An alien. Literally space-ian. Person from space. - gaijin 外人

Outsider. A foreigner. A person from:- soto 外

Outside. - kaigai 海外

Outside the sea. Beyond the sea. (because Japan is surrounded by...) - umi 海

Sea. - So anyone from beyond the sea is a foreigner.

- soto 外

By the way, it's all bito びと instead of hito ひと because it's a suffix affected by rendaku 連濁, which adds a diacritic to the first syllable. This doesn't always happen, but it happens under certain circumstances.

- shinu 死ぬ

shi-nu しぬ

To die. - kami 神

ka-mi かみ

God. - shinigami 死神

shi-ni, ga-mi しにがみ

God of death.

A similar thing is the sokuonbin 促音便 which adds the small tsu っ:

- nichi 日

Day. - ki 記

An account. (in the sense of a record, chronicle, story, not a bank account.) - nichi-ki 日記

ni-chi-ki にちき

(no.) - nikki 日記

ni-k-ki にっき

(yes.)

Diary.- Mirai Nikki 未来日記

Future Diary.

- Mirai Nikki 未来日記

Reading Kanji

As you've probably noticed already, the kanji are an ungodly aberration that makes anyone with a semblance of sanity trying to learn the Japanese think: "what kind of baka thought this was good idea???"Unfortunately, what's done is done. The kanji exist. Japanese is written with it. You have to learn them.

Okay, but how many kanji are there?

There are 50 or so hiragana and katakana. That totals 100 characters. Wow, that's a lot. Way more than our humble 26 Latin alphabet letters.

Then there are 2000 kanji.

...

Yep.

Two thousand kanji.

Number of Kanji

Technically, there are more than 2000 kanji. There should be tens of thousands of kanji. The number 2000 is the number of Jouyou Kanji 常用漢字, "normal use kanji." These are the only ones taught in school and the only ones used in official governmental publications.This is the number you need to know to be literate.

Some words were written with other kanji before a major orthographic reform. For example, mawaru 回る used to be spelled mawaru 廻る. But when selecting those 2000 kanji, the government kept 回 and tossed out 廻.

All words that were spelled with 廻 had their official spelling changed to something that was part of those 2000 jouyou kanji. Thus, almost all words in modern Japanese are spelled with those 2000 kanji.

Learning Kanji

The first 1000 kanji are taught through 6 years of primary school, while the last 1000 are taught in the 3 years of middle school. That doesn't mean a a primary school student won't know how to read an advanced kanji, just that the school doesn't test that kanji yet.This means a normal Japanese person learns less than 5 kanji per week, and eventually learns all the kanji they need to know.

Compared to that, people learning Japanese try to force themselves into learning absurd numbers of kanji at once. Like memorizing 40 kanji per week so you get to 2000 in just one year.

There are various methods to do this. Making up stories or something to remember each character, mnemonics, or memorizing them by how you handwrite them, by their components, for example:

- omoi 重い

Heavy. - chikara 力

Strength. - If you know how to write heavy and strength, you know how to write this:

- ugoku 動く

To move.- Ah, yes, movement, applying force (strength) to matter (heavy), of course.

- And an easier one:

- ki 木

Tree. - hayashi 林

Woods. (a bunch of trees.) - mori 森

Forest. (a lot of trees.)- Pretty sure I've seen this in Pokémon before.

This works with many words since the components of a kanji weren't chosen randomly.

- kin 金

Gold - gin 銀

Silver. - dou 銅

Copper. - tetsu 鉄

Iron.

Source: japanesewithanime.com (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Except it's more complicated than that. For example, kaeru 蛙, "frog," has the insect component even though it isn't an insect.

This happens because, in the past, everything that wasn't

Many learners try learning 2000 kanji through SRS (Spaced Repetition Systems) end up hating the entire process and feeling very burned out. So I don't recommend it.

In particular, some learners waste time checking all possible readings and meanings of each kanji per grade level. That is a bad idea.

Some meanings and readings are extremely rare. And what's tested per grade level in Japanese schools isn't all the readings of a kanji, but only the reading used in certain common words. It tests if a student can read a real word, not if they can read the kanji by itself.

In particular, some kanji with multiple readings have the appropriate reading hinted by the kana that comes after it. In this case, that kana is the called the okurigana 送り仮名.

- 細 means "fine."

- 細い is read hoso.i ほそい.

It means "thin." - 細かい is read koma.kai こまかい.

It means "detailed."

Above, the i-adjectives hosoi and komakai are spelled with the same kanji, but when the okurigana is i い, it's spelling the word hosoi, and when it's kai かい, it's the word komakai.

In other words, you'll never see just this character "細" alone with the reading of "hoso" or "koma." You only read it that way when you have the appropriate okurigana right after it.

The same thing happens to verbs:

- kuda.ru 下る

To descend. - sa.garu 下がる

To lower. - o.rosu 下ろす

To drop.

When conjugating stuff in Japanese, the kanji can't be conjugated. That is, only the kana at the end changes.

- tanoshi.i 楽しい

Fun. - tanoshi.kunai 楽しくない

Not fun. - tanoshi.katta 楽しかった

Was fun. - tanoshi.kunakatta 楽しくなかった

Was not fun.

Once you've memorized ~kunai, ~katta, and the other endings, you'll know that any word that ends with ~katta, for example, has a kanji that should be read like if its okurigana ended in ~i.

- kawai.katta 可愛かった

Was cute.- In the dictionary, the word will be:

- kawai.i 可愛い

Cute.

The okurigana is crucial to figuring out the reading of a kanji. Just memorizing its readings in a vacuum won't work. You need to get used to how it works in practice, as soon as possible. Learn the words, and not the kanji in isolation.

But don't worry, Japanese natives aren't born with kanji preloaded into their heads.

Reading Japanese

Stories for little children do not have kanji at all. DO NOT READ THEM.Separating Words

Real Japanese has kanji, and it's actually easier to tell where a word starts and ends if the phrase has kanji in it. This happens because Japanese doesn't use spaces like English does. Observe:- kinonotabi

きののたび

(this is all hiragana, so I don't know where something starts and ends.) - Kino no Tabi

キノの旅

Kino's Journey.- Kino - katakana, not a native word.

This is the name of the character. - no - hiragana, grammar particle.

Marks Kino with the genitive case. (see no-adjectives.) - tabi - kanji, noun.

- Kino - katakana, not a native word.

- jojonokimyounabouken

じょじょのきみょうなぼうけん

(no idea.) - JoJo no Kimyou na Bouken

ジョジョの奇妙な冒険

JoJo's Bizarre Adventure.- JoJo - katakana, not a native word.

Name of character, again. - no の - hiragana, particle.

(genitive case.)

Jojo's. - kimyou - kanji, adjective.

Bizarre. - na な - hiragana, particle.

This makes the na-adjective kimyou qualify the noun that comes after it. - bouken - kanji, noun.

Adventure.

- JoJo - katakana, not a native word.

- anohimitahananonamaewobokutachiwamadashiranai.

あのひみたはなのなまえをぼくたちはまだしらない。

(dunno.) - {ano hi mita} hana no namae wo boku-tachi wa mada shiranai.

あの日見た花の名前を僕達はまだ知らない。

The name of the flower [that] {[we] saw that day} we still don't know.- This complex sentence contains a {relative clause}.

- ano - hiragana, demonstrative pronoun. (see: kosoado kotoba)

That. - hi - kanji, noun.

Day. - mita - mixed, verb.

Saw. - hana - kanji, noun.

Flower. - no - hiragana, particle.

(genitive case.)

Flower's. - namae - kanji, noun.

Name. - wo - hiragana, particle.

(marks "flower's name" with accusative case, making it the direct object.) - boku - kanji, pronoun.

I. Me. - tachi - kanji, suffix.

(pluralizing suffix.)

We. Us. - wa - hiragana, particle.

(marks "we" as the topic.) - mada - hiragana, adverb.

Still. - shiranai - mixed, verb.

Don't know.

As you can see above, the fact that you switch between kanji and kana helps you tell where things start and end.

This is mostly because verbs and adjectives normally start with kanji and end in kana, so if you see a kanji character, that's probably where a word starts. And then there's particles spelled in hiragana separating kanji nouns from other kanji nouns.

Disambiguating Words

Another important function of the kanji is that it helps disambiguate words that would be spelled literally the same with kana. For example:- kanji 漢字

Chinese characters. - kanji 感じ

Feeling.- From kanjiru 感じる, "to feel."

These are called homonyms, and Japanese is full of them.

- Maria-san juu-nana-sai

マリアさん十七歳

Maria-san is 17 years old.- juu 十

Ten. - nana 七

Seven.

- juu 十

- Maria san-juu-nana-sai

マリア三十七歳

Maria is 37 years old.- san 三

Three. - san-juu 三十

Thirty.

- san 三

Reading Aids

You want to read something that has kanji just like the real Japanese language does, but the problem is: you can't read kanji. So what do you do?Fortunately, manga made for younger audiences, like shounen manga, are made with the fact that Japanese has 2000 kanji in mind. These come with reading aids called furigana 振り仮名, also known as the patron saint of Japanese learners, that aids you read stuff.

- 振り仮名(ふりがな)

fu ふ, ri り, ga が, na な is sometimes placed in parentheses right after the word.

The furigana is usually kana written in a small size besides a kanji that shows how you're supposed to read it. Not all manga have it, but most modern manga made for children have furigana for literally every kanji. The only exceptions being very basic stuff like numbers.

Manga like JoJo have been in publication for decades. The first volumes didn't have furigana, but the later volumes started having furigana on it.

In manga for older audiences, there's no furigana. Except the furigana showing how to read the names of people, the furigana for unusual words that you rarely see, the furigana for common words that are commonly spelled with katakana, and so on.

For example, names of animals are often spelled without kanji. After all, the kanji for "leopard," hyou 豹, only means leopard. It's not unusual and not shared by common words, so it's not part of the jouyou kanji. Consequently, it's sometimes spelled hyou ヒョウ, or with furigana.

Warning: sometimes authors will use the furigana space to write stuff that's not the actual reading of the kanji. This is called a gikun 義訓 and it's used as a sort of wordplay. You'll eventually come across it, whether you want to or not, but at least you know there's a name for it now.

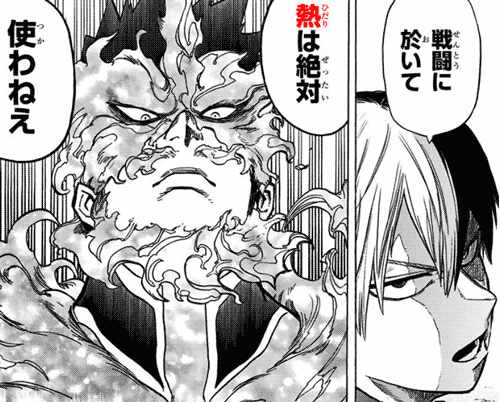

Manga: Boku no Hero Academia, 僕のヒーローアカデミア (Chapter 28, 策策策)

- Context: Todoroki Shouto 轟焦凍 has both cold and heat abilities, which come from the sides of his body: from the right comes cold, from the left comes heat.

- sentou ni oite

netsu (hidari) wa zettai

tsukawanee

戦闘に於いて熱(ひだり)は絶対使わねえ

In battle [I] absolutely won't use heat (left).- In other words: he said he won't use "heat," netsu 熱, by saying he won't use the "left" side, hidari 左.

One problem of reading manga with furigana is that you can't copy the text. If you read a physical manga, you can't just pinch the kanji with your fingers and throw it on Google. You can't do it with a digital manga, either.

There's OCR (Optical Character Recognition) software that can help. Some people look the characters by their components in online dictionaries like Jisho. Other people try drawing the character on Google Translate. It's actually pretty good at recognizing characters.

If this doesn't sound good enough for you, you can try reading web novels on a website like shousetsuka ni narou 小説家になろう. A bunch of isekai came from that site, like konosuba and re:Zero.

Since they are web pages you can copy-paste the text into an online dictionary, but since they're novels there will be a lot of text. And worst of all: NO PICTURES.

If that still doesn't sound good enough for you, then just type the Japanese name of your favorite anime on Twitter and go read what people say about it in Japanese or something. (don't do it if it's a manga adaptation though, or you'll get spoilers. Only original anime like TTGL or conclusive adaptations like Ansatsu Kyoushitsu.)

Other Symbols

For reference, some other symbols you'll often encounter learning Japanese.The kurikaeshi 々 is an iteration mark that repeats the previous kanji.

- hito-bito 人人

hito-bito 人々

People. - toki-doki 時時

toki-doki 時々

Sometimes.

The term reduplication refers to words that repeat themselves like the above. In Japanese, reduplication often happens with onomatopoeia and mimetic words.

- dokidoki ドキドキ

*thump thump* (heart beating.) - gogogogo ゴゴゴゴ

*menacing* (shows up in JoJo.) - zawa.. zawa.. ざわ・・ざわ・・

*anxious* (shows up in Kaiji.) - wakuwaku ワクワク

*excited* - pakupaku パクパク

*opening and closing, flapping*- pakkuman パックマン

Pacman.

- pakkuman パックマン

There are iteration marks for the kana, ゝゞヽヾ, but they're rarely used.

- kokoro 心

kokoro こころ

kokoro こゝろ

Heart.

The symbols 〻〱〲 are other iteration marks that are rarely used.

Source: japanesewithanime.com (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The small ke ヶ is not a kana. It's a simple way to write 箇 when talking about months, for example.

- ikkagetsu 一箇月

ikkagetsu 一ヶ月

One month. - nikagetsu 二ヶ月

Two months. - etc.

Source: japanesewithanime.com (CC BY-SA 4.0)

In names of places, and names of characters that come from names of places, it's read as ga が, and has the same possessive meaning the no の particle has.

- senjou no hara

戦場の原

Plains of battlefield. - senjou ga hara

戦場が原

(same meaning.) - Senjougahara

戦場ヶ原

(same meaning.)

This works just like:

- waga na wa Megumin!

我が名はめぐみん!

My name is Megumin!

These 「」『』 square-y things are quotation marks.

Source: japanesewithanime.com (CC BY-SA 4.0)

When there are dots in the furigana space, those are the bouten 傍点, "emphasis marks." This works pretty much like bold letters in English, or underlined words.

i love your post <3 (/*3*)/

ReplyDelete".... for example, only ka か and ra ま"

ReplyDeleteLittle typo there :)

Thanks. Fixed it.

DeleteVery informative. Much thanks! ^_^

ReplyDeleteขอบคุณครับ จาก ประเทศไทย

ReplyDeleteドキドキする

ReplyDeleteVery informative,Thank you

ReplyDeleteThis helped me so much! ありがとございます!

ReplyDeleteありがとございます! this help so much!!

ReplyDeleteすごい! ありがとう。

ReplyDelete