In Japanese, watashi 私, ore 俺, boku 僕, and various other words, all mean "I" or "me," that is, they're Japanese "first person pronouns," ichininshou daimeishi 一人称代名詞.

But why are there so many ways to say "I" and "me" in Japanese? What's the difference between them?

The basic gist is that some pronouns, like watashi, are used by women, while other pronouns, like ore and boku, are used by men, except that in business and formal contexts everybody uses watashi, except some men use boku or watakushi ワタクシ instead. It's complicated.

If you're learning Japanese and are unsure of what pronoun to use, just use watashi until you become sure.

Grammar

The grammar of first person pronouns is the same no matter the pronoun, that is, watashi, ore, boku, etc., all work exactly the same way in a sentence, and you can replace watashi by ore or boku in any sentence keeping the same literal meaning. For example:

- watashi wa Tarou desu

私は太郎です

I'm Tarou. - ore wa Tarou desu

俺は太郎です - boku wa Tarou desu

僕は太郎です

Skip to Difference Between Pronouns if you aren't interested in learning Japanese grammar and just want to know why some anime characters use a pronoun while others use another..

"I" and "Me" in Japanese

In English, "I" and "me" are subject and object first person pronouns, respectively. This means that when the first person is the subject, which comes before the verb, we say "I," but when the first person is the object, we say "me." For example:

- I talked to him. (correct.)

- Me talked to he. (wrong.)

- He talked to me. (correct.)

- Him talked to I. (wrong.)

In Japanese, there's no such distinction—the same word used when the first person is the subject is also used when the first person is the object. As such, watashi, etc., can translate to either "I" or "me" depending on the sentence.

Furthermore, in Japanese, it's not the word order that determines what word is the subject, but merely what particle comes after the word. If it's a subject-marking particle, it's marked as subject, if it's an object-marking particle, it's marked as object, and so on.

Observe:

- watashi ga okuru

私が送る

I send.- ga が particle - subject marker.

- watashi ga - the subject of the clause.

- watashi wo okuru

私を送る

Send me. (literally, like put me into a mail box or something)- wo を particle - direct object marker.

- watashi wo - the object of the clause.

- watashi ni okuru

私に送る

Send to me. (an e-mail etc.)- ni に particle - indirect object marker.

- watashi ni - the indirect object of the clause.

"We" and "Us" in Japanese

Japanese doesn't have separate words for "we" and "us." To create a plural first person pronoun, you take a singular first person pronoun add a pluralizing suffix.

- watashi-tachi mo tetsudau

私達もて伝う

We will help, too. - watashi-tachi wo tasukete!

私達を助けて!

Save us!

This is similar to how in English we add the suffix "~s" to the singular "cat" to get the plural "cats."

However, in Japanese, there are multiple pluralizing suffixes, they're normally only used toward individuals, people, not animals, and some are used with certain pronouns more than others. In summary:

"My," "Mine," "Our," "Ours"

Japanese doesn't have separate words for "my," "mine," "our," "ours," either.

In this case, the no の particle, which can create a possessive no-adjective, is used in front of the pronoun to turn it into a possessive pronoun. For example:

- watashi no namae wa Tarou desu

私の名前は太郎です

My name is Tarou. - sore wa watashi no desu

それは私のです

That is mine. - ore-tachi no teki da

俺たちの敵だ

[It] is our enemy.

Omission

In Japanese, it's unnatural to use a first person pronoun in every sentence.

For example, instead of saying:

- {boku ga shinitai} no de boku ga kaerimasu

僕が死にたいので僕が帰ります

{I want to die} so I will go home.

You'd just say:

- {shinitai} no de kaerimasu

死にたいので帰ります

{[I] want to die}.so [I] will go home.

And it's implicit that you're talking about yourself in both clauses: it's you who wants to die, and it's you who will go home.

Since it's implicit, you don't need to say watashi, boku, or ore every time you'd say "I" in English, in spite of those words translating to "I" in English. That is, just because the English version has "I," that doesn't mean the Japanese version will have a first person pronoun.

The reasons for this are a bit complicated. It boils down to:

- You don't need to use a first person pronoun when it's implicit that you're talking about yourself.

The question is, then, what situations it's implicit and what situations it's not.

Due to Continuation

In general, when talking about yourself, you'll always use the first person pronoun, except that in some cases it's obvious that you're talking about yourself, so you won't need the pronoun.

This occurs, for example, when you have started talking about yourself in a sentence, and continue talking about yourself in the next sentence. It's obvious that you're still talking about yourself, and as such you don't need to repeat the pronoun.

- Context: it's Christmas and a grade school student is cleaning the school windows. But why?

- watashi kyonen wa ii ko

janakatta

mitai de Santa-san

kite-kurenakatta-n-desu

私去年は良い子じゃなかったみたいでサンタさん来てくれなかったんです

It seems last year I wasn't a good child so Santa-san didn't come [for me]. - dakara kotoshi wa

ii ko ni narou to

omotte!

だから今年は良い子になろうと思って!

[That's why] [I] thought: this year [I] will become a good child!- watashi wa X to omotta

私は〇〇と思った

I thought that X. - watashi ga ii ko ni naru

私が良い子になる

I will become a good child.

- watashi wa X to omotta

Due to Question-Answer

Normally, a conversation will be a zig-zag of someone asking "what do you think?" and someone answering "I think that," or "did you do this," and "I did that." The "you" is implicit in questions, and the "I" is implicit in answers.

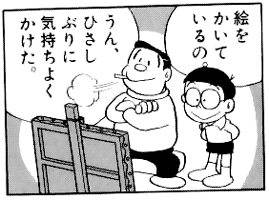

- Context: Nobi Nobita 野比のび太 talks to his father.

- e wo kaiteiru no.

絵をかいているの。

Are [you] drawing a picture?- no の sentence ending particle - used to ask questions.

- un, hisashiburi ni {kimochi-yoku} kaketa

うん、久しぶりに気持ちよくかけた。

Yes, for the first time in a while [I] was able to draw [it] {feeling good}.- kimochi-ii 気持ちいい - good-feeling, i.e. feeling satisfied with how they drew it, feeling pleasant as they drew it, etc.

Above, neither character used a pronoun in Japanese, even thought we had to use the pronouns "I," "you," and "it" in the English translation.

By the way, Japanese doesn't have an "it" pronoun for reasons similar to why it doesn't need first person pronouns in every sentence.

When answering questions about third persons with sentences that feature multiple, different subjects, things become a little complicated. For example, if someone asks:

- kare wa nani wo shite-iru?

彼は何をしている?

He is doing what?

What is he doing?

Above, the topic and focus of the sentence are "he" and "is doing what," respectively. This topic, marked by the wa は particle, carries over to the answer.

- hon wo yonde-iru

本を読んでいる

[He] is reading a book. - kare wa hon wo yonde-iru

彼は本を読んでいる

The sentence topic can only be marked in the matrix clause, and it can have all sorts of roles, subject, object, etc.

When you have two clauses, with two subjects, whether you use the topic-marker wa は or the subject-marker ga が changes the meaning of the sentence entirely, because wa は is going to end up the matrix clause, while ga が is assumed to be inside a subordinate clause.

Observe:

- {watashi ga katta} hon wo yonde-iru

私が買った本を読んでいる

[He] is reading the book [that] {I bought}. - kare wa {watashi ga katta} hon wo yonde-iru

彼は私が買った本を読んでいる

Above, we have the relativized object hon, and the subject of the relative clause is watashi ga, so it's a book "that I bought."

With an explicit topic, we'd say kare wa before the relative clause, "before" as in "outside of it, in the matrix." If we used watashi wa instead, it would replace kare wa in the matrix:

- watashi wa {katta} hon wo yonde-iru

私は買った本を読んでいる

I'm reading a book [that] {[someone] bought}.

I'm reading a book [that] {[I] bought}.

Since watashi wa is in the matrix, the relative clause {katta} ends up without an explicit subject. Although this is allowed in Japanese, the sentence won't answer "what he is doing" at all, because we changed the topic from kare wa to watashi wa.

Due to Semantics

Some statements only make sense when associated with the individual speaking, which allows for the first person interpretation all the time.

For example, sentences that express cognition, what you think, feel, etc., assume first person, given that you can only really tell about your own feelings, not the feelings of other people.

- ~to omou

~と思う

[I] think that... - shiranai

知らない

[I] don't know about [it]. - wakaranai

わからない

[I] don't understand [it].

[I] don't know, in the sense of I know about it, but I don't know what it means. - ~tai

~たい

[I] want to...

Some such cognitives are adjectives in double subject constructions that translate to English as stative verbs. Some examples:

- watashi wa {neko ga suki da}

私は猫が好きだ

{Liked is true about cats} is true about me.

I like cats. - {neko ga suki da}

猫が好きだ - watashi wa {kumo ga kowai}

私は蜘蛛が怖い

{Scary is true about spiders} is true about me.

I fear spiders. I'm afraid of spiders. - {kumo ga kowai}

蜘蛛が怖い

Physical sensations follow the same pattern, but with body parts as one of the subjects.

- watashi wa {atama ga itai}

私は頭が痛い

{Painful is true about head} is true about me.

My head hurts. - {atama ga itai}

頭が痛い - {hara ga hetta}

腹が減った

[I] am hungry. - {senaka ga kayui}

背中が痒い

[My] back is itchy.

The first person pronoun is omitted is when a sentence has auxiliary verbs of giving and receiving, such as ~te-ageru ~てあげる and ~te-kureru ~てくれる. With ~te-ageru, the giver is implicitly the first person, and with ~te-kureru, the receiver is the first person.

- oshiete-ageru

教えてあげる

[I] will tell [you]. - oshiete-kureru

教えてくれる

[He] will tell [me].

Both verbs above work the same way. The difference between them is nuance. With ~te-ageru, the giver is inferior to the receiver, while with ~te-kureru the receiver is inferior to the giver.

The assumption is that the inferior one is always the speaker, since branding yourself as inferior implies humility, so the speaker becomes subject with ~te-ageru and object with ~te-kureru.

In anime, in rare cases an arrogant character uses ~te-kureru with them as subject, which means they're doing something for someone whom they consider inferior to them. Although this usage is grammatically possible, it never happens in real life.

Imperative sentences, orders, have an implicit "you," while performative sentences have an implicit "I."

- damare

黙れ

Shut up. (as in, YOU shut up.) - onegai shimasu

お願いします

[I] beg [you].

Please. - chikaimasu

誓います

[I] swear. - tanomu

頼む

[I] entrust [this task] to [you].

I leave it to you.

Please do it for me.

In many cases, to deliberate use the watashi wa particle in a situation where it's not needed creates the contrastive wa は nuance. A normal contrastive sentence has two topics in parallel, with information contrasting one against the other, for example:

- watashi wa neko ga suki dakedo, Tarou wa kirai da

私は猫が好きだけど、太郎は嫌いだ

I like cats, but Tarou hates [them].

With only one topic, you have a nuance like this:

- watashi wa neko ga suki

私は猫が好き

I like cats.

I don't know about other people, but I do like cats.

It's me who likes cats, not other people.

In particular:

- watashi wa ii kedo

私はいいけど

That's fine with me, but [I don't know if it's fine with other people].

This usage comes naturally when asking multiple people the same question, since each answer contrasts with each other:

- inu to neko, docchi ga suki?

犬と猫、どっちが好き?

Dogs or cats, which one do [you] like? - watashi wa neko ga suki

私は猫が好き

I like cats. - ore wa inu

俺は犬

As for me, dogs.

I [like] dogs.

Although the topic marked by wa は is always in the matrix, the contrast marked by wa は isn't necessarily in the matrix.

This is particularly confusing when used with a cognitive verb, such as omou 思う, "to think," kangaeru 考える, "to consider," shinjiru 信じる, "to believe," utagau 疑う, "to doubt," and so on, because such verbs assume first person in nonpast form, but not in ~te-iru ~ている form.(山本, 2005:98)

- {kare wa sou da} to omou

彼はそうだと思う

[I] think [that] {he is that way}. (even thought other people aren't that way.)- watashi wa "kare wa sou da" to omou

私は「彼はそうだ」と思う

- watashi wa "kare wa sou da" to omou

- kare wa {sou da} to omotte-iru

彼はそうだと思っている

He thinks {[it] is that way}.

The reason for the above is complicated. Something that occurs physically must occur at some point in time, so they're bound to a temporal episode, and expressed through episodic predicates. By contrast, things that don't occur at any particular time are gnomic. One's own thoughts are gnomic states, since they don't occur physically, and gnomic states are expressed through the nonpast form. We can't know what other people's thoughts are unless they express those thoughts physically, by literally telling us, and so we only know what they thought at a particular time (episode), so we report as episodic states, which are expressed through the ~te-iru form.

Similarly, while ~tai ~たい, "want to," assumes first person, ~tagaru ~たがる assumes otherwise, as it means something closer to someone "looks like they want to" do something.

- piza φ tabetai

ピザ食べたい

[I] want to eat pizza.- φ (Greek letter phi) - symbolizes the null particle in analysis.

- piza φ tabetai?

ピザ食べたい?

Do [you] want to eat pizza? - piza φ tabetagatte-iru

ピザ食べたがっている

[He] looks like he wants to eat pizza.

Relativization

Japanese first person pronouns can easily become relativized, even thought the same doesn't occur as easily in English. For example:

- watashi wa binbou da

私は貧乏だ

I'm poor. - {binbou na} watashi

貧乏な私

I, [who] {is poor}.

The {poor} me.

Since first person pronouns always unambiguously refer to the speaker, all relative clauses on first person pronouns are nonessential, and only exist to add some extra relevant information for emphasis, like:

- {kayowai} watashi ni wa muri desu

か弱い私には無理です

It's impossible for me, [who] {is weak}.

For the {weak} me, [such thing] it's impossible.- watashi wa kayowai

私はか弱い

Weak. Feeble.

- watashi wa kayowai

- {omae wo shinjiru} ore wo shinjiro

お前を信じる俺を信じろ

Believe me [who] {believes you}.

First person pronouns can also be qualified by the demonstrative "this," kono この, even though this never happens in English.

See kono ore da! この俺だ! for examples.

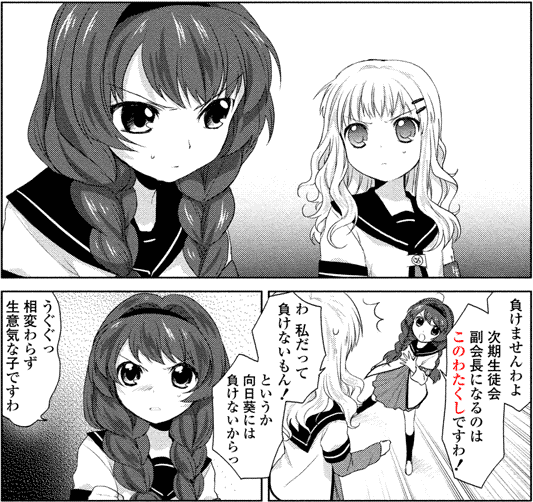

- Context: Furutani Himawari 古谷向日葵 competes with Oomuro Sakurako 大室櫻子 for the student council presidency.

- makemasen wa yo

負けませんわよ

[I] won't lose. - *places hand on herself*

- {jiki seitokai fukukaichou ni naru} no wa kono watakushi desu wa!

時期生徒会副会長になるのはこのわたくしですわ!

The one [who] {will become the next student council vice-president} is this me!

It's I [who] {will become the next student council vice-president}. - wa, watashi datte makenai mon!

わ 私だって負けないもん!

I-I won't lose [either]! - toiuka Himawari niwa makenai kara'

というか向日葵には負けないからっ

Or rather, [I] wouldn't lose to [you], Himawari. - ugugu'

うぐぐっ

*frustration* - aikawarazu {namaiki na} ko desu wa

相変わらず生意気な子ですわ

As always, [you] are an {impertinent} child. (literally.)

[You] are impertinent as always.

Differences Between Pronouns

There are various differences difference between watashi, ore, boku, etc.

These words express "how you call yourself," in other words, "who do you think you are."

It's normal for a single person to use various, different pronouns in a single day, depending on whom they're talking with, and how they wish to present themselves to that person.

One pronoun used casually, among friends, another used when talking to strangers, may another one used professionally, when talking to coworkers, and another used when talking to clients or one's boss.

It's also normal for someone to change pronouns through their life, using one pronoun as a child, one as they go through school, one when they enter the workforce, and one when they're elderly.

The pronoun changes according to one's self-image.

All things considered, pronouns vary in:

- Age. Some are used by children, others by elders.

- Gender. Some are masculine, others feminine.

- Humility. Some are humble and polite, others are arrogant and rude.

- Formality. Some are casual, others formal, and others are literary.

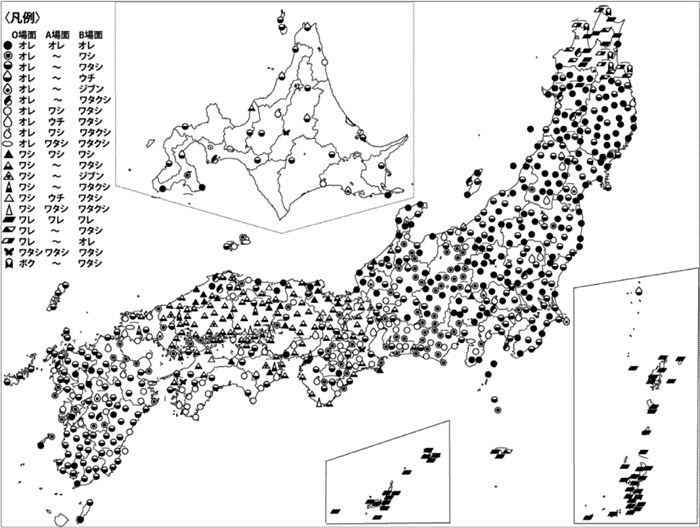

Furthermore, some pronouns change in nuance from region to region. Most of the time we'll be talking about the Kantou 関東 region, in which is Tokyo 東京. Some pronouns are typical of Kansai 関西, others are considered more polite in some regions than in others, and so on.

Some pronouns aren't used at all in some regions. Sometimes a pronoun is only known from anime characters using it, or from it being used on the internet, or it's some archaic pronoun nobody uses anymore, or a pronoun that a normal person would never use.

The pronoun wai ワイ, for example, is used in very few regions, but used on the internet because it sounds funny like "yay." A person who uses wai may move to another region, to study in an university, for example, and get greeted with weird looks by people who thought nobody would actually use that pronoun.(negiyan.me)

- Context: a map showing the usage of first person pronouns by men, across various regions of Japan, and in different "situations," bamen 場面. The labels O-bamen, A-bamen, and B-bamen refer to the usage with friends, that doesn't require politeness, with random people, which requires minimum politeness, and with superiors, that require added politeness, respectively. The study is a bit old: the surveyed were born in 1891–1931. Noteworthy is that, while in most regions watashi and its variants are used in situations that require added politeness, in a few regions ore 俺 is used instead, and that uchi ウチ, which is typically considered a feminine pronoun, is also used by men in some regions.

Character Personality

In anime, manga, and fiction in general, the pronoun a character uses is part of that character's profile, and is used to hint their personality and background.

This is called yakuwarigo 役割語, "role language," and it's not limited to first person pronouns, also including all sorts of speech mannerisms.

Because role language is widely employed, the pronouns characters use in anime often fail to reflect how pronouns are used in Real Life™, Japan.

In particular, the characters traits are exaggerated to the point that you always expect a certain archetype of character to use a certain pronoun, and nothing else.

In some cases, the pronoun used is nothing but a quirk. Using a pronoun that's opposite to what you'd expect creates a gap between the character traits that's sometimes called gap moe ギャップ萌え.

Differences in Spelling

In manga and novels, the spelling of a pronoun can also be a subtle hint of a character's personality.

In Japanese, a single word can be spelled in multiple ways, with all three "alphabets:" the hiragana ひらがな, katakana カタカナ, and kanji 漢字.

Aesthetically, hiragana looks chummy, katakana looks cool, and kanji looks serious.

Normally pronouns will be spelled with kanji, unless they're homonymous with another pronoun. If a character is a child, the pronoun may be spelled with hiragana instead. They're spelled with katakana to emphasize the pronunciation more than the meaning, or just because it looks cooler.

List

For reference, a list of Japanese first person pronouns, and details about their usage.

Watashi 私

The pronoun watashi 私 is the most common Japanese first person pronoun.

In casual contexts, men generally use a masculine pronoun like ore, while women use watashi. In formal and business contexts, both genders are expected to use watashi.

If you're a woman, you don't have to worry about it, and you can just use watashi all the time, however, if you're a man, you could sound feminine, by comparison, if you're using the neutral watashi when talking to a bunch of men who are using more masculine pronouns.

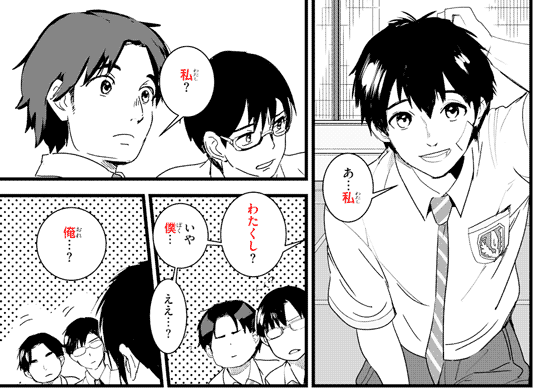

- Context: Miyamizu Mitsuha 宮水三葉, who is a girl, switches bodies with Tachibana Taki 立花瀧, who is a boy. Upon meeting Taki's school friends, she has trouble figuring out the appropriate first person pronoun to use as a boy.

- a... watashi

あ…私

Ah... I... - watashi?

私?

"Watashi?"- His friends look puzzled.

- watakushi?

わたくし?

"Watakushi"?- Nope.

- iya boku...

いや 僕…

Erm... "boku"?

- Nope.

- ee...?

ええ…?

Eeh...?- Hang in there, Mitsuha!

- ore....?

俺…?

"Ore"?- *nods*

Nevertheless, some men do use watashi regardless of context, perhaps because they want to transmit a more professional self-image.

- Context: All Might オールマイト is a super hero who always says a certain phrase when he arrives somewhere to beat up villains and save people.

- watashi ga kita

私が来た

I came. (literally.)

I am here. (usually translated as this because of reasons.)

- kita - past form of kuru 来る, "to come [here]."

The usage of watashi puts a necessary distance between you and the listener in professional contexts, but, on the other hand, between friends it may feel too distant.

For example, which pronoun do you use when talking to your girlfriend's parents for the first time? Using watashi or boku may feel too distant, using ore may feel to close. The pronoun implies what you think your relationship with them is, and they may not agree with what you think.

The spelling watashi ワタシ, with katakana, can be used to emphasize the pronunciation of the word, specially if it's pronounced unnaturally, in a more stiff way, e.g. by a character who's a foreigner and not very fluent in Japanese.

The kanji of watashi is also used in some other words, like:

- shiritsu gakkou

私立学校

Private school. - shiyou

私用

Private use.

When watashi is part of the title of a series, it's likely to have a female protagonist. For example:

- Watashi ga Motete Dousunda

私がモテてどうすんだ

[What's The Point of] Me Being Popular? - {Watashi ga Motenai} no wa Dou Kangaetemo Omaera ga Warui!

私がモテないのはどう考えてもお前らが悪い!

No Matter How [You] Think About [It], [It] is You Guys Fault {I'm Not Popular}. - Watashi φ, Nouryoku wa Heikinchi de tte Itta yo ne!

私、能力は平均値でって言ったよね!

I Said [I Wanted] Average Abilities, [Didn't I]?! - Jitsu wa Watashi wa

実は私は

The truth is I... (something) - Maji de Watashi ni Koi Shinasai!

真剣で私に恋しなさい!

Fall in Love With Me For Real!

Ore 俺

The pronoun ore 俺 is the most common first person pronoun among men, which means most men use ore with someone, not that men use ore all the time.

The pronoun ore is normally used with friends, in casual contexts. It's a masculine pronoun, that tells everybody "I'm a man."

In Japan, masculinity seems associated with being assertive, arrogant, and rude. By contrast, being passive, reserved, and polite is associated with femininity.

- The terms soushokukei danshi 草食系男子, "herbivore guy," and nikushokukei joshi 肉食系女子, "carnivore girl," to a romantically passive guy and assertive girl, respectively, which is contrary to the stereotype.

Using ore makes you sound more manly than using boku or watashi. Some women prefer men that use ore. On the negative side, using ore also sounds very antagonizing, so some men prefer not to use it, and instead use the softer boku.

In contexts that demand respect, ore is often avoided. This includes business contexts, when speaking to one's clients, or one's superiors, one's boss, manager.

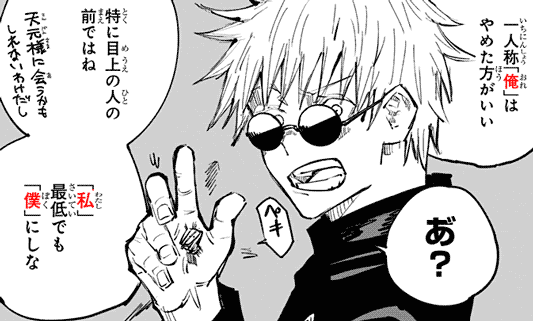

- Context: Gojou Satoru 五条悟, who doesn't like to obey rules, is told to obey societal norms.

- ichininshou "ore" wa {yameta} hou ga ii

一人称「俺」はやめた方がいい

[It] would be better if {[you] stopped} [using] the first person pronoun "ore." - a´?

あ゙?

Ah?

- What did you just say to me???

- toku ni {me-ue no} hito no mae dewa ne

特に目上の人の前ではね

Specially in front of [your] superiors, [alright].- {me-ue no} hito

目上の人

People [who] {are above you}.

[Your] superiors.

- {me-ue no} hito

- {Tengen-sama ni au kamoshirenai} wake dashi

天元様に会うかもしれないわけだし

{[We] might meet Tengen-sama}, [after all].- In this series, Tengen-sama is an important person, as hinted by the fact the ~sama suffix is used with their name.

- "watashi", saitei demo "boku" ni shi na

「私」最低でも「僕」にしな

Use "watashi," at very minimum "boku," [okay].

Some men will not use ore when talking to their mother, or in front of women, even if they use it when talking to their male friends.

- In Bakuman. バクマン。, Mashiro Moritaka 真城最高 uses boku with his mother, but ore with his best friend.

Conversely, sometimes a character that normally uses a softer pronoun will change to ore when standing up for something, or to put on airs in front of a girl, to look more manly than usual.

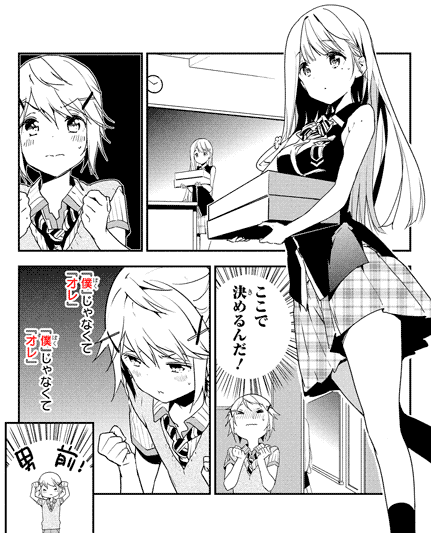

- Context: Shuri Kojuurou 朱里小十郎, a boy who looks like a girl, fell in love with Fujinomiya Neko 藤ノ宮寧子, and now he's trying to look more manly in order to impress her, starting by changing his first person pronoun from boku to ore.

- koko de kimeru-n-da!

ここで決めるんだ

[I have to get it right] here! (it's now or never!)- kimeru

決める

To settle. To decide.

To score a goal. To carry something out successfully.

- kimeru

- "boku" janakute "ore"

「僕」じゃなくて「オレ」

Not "boku," "ore." - "boku" janakute "ore"

「僕」じゃなくて「オレ」

Not "boku," "ore." - otoko-mae!

男前!

Handsome!

In general, using ore with polite language (desu, ~masu) is avoided, since ore sounds rude, so it doesn't make a lot of sense to combine it with politeness.

However, some men use ore when talking to one's equals and subordinates, switching to watashi only when talking to their superiors. In this case, they may use polite language and ore with their equals, for example.

In series with gangs, delinquents, yankii ヤンキー characters, such characters always use ore, but may also use polite language when talking to the boss of the gang, and so on. Sometimes, they use ~ssu ~っす instead of desu and ~masu.

Arrogant characters generally use ore. Sometimes, a ridiculously arrogant character, boastful and full of himself, who look down upon others, will use ore-sama 俺様.

The honorific suffix ~sama ~俺 is more respectful than the usual ~san ~さん. It tends to be used to servants to refer to their masters, and as such it has a connotation that the person referred to by ~sama is superior to the person talking.

By using the honorific, the character reversely implies he's superior to the listener. Naturally, nobody would use this pronoun seriously in real life, that would be extremely cringe.

- Context: Takamine Kiyomaro 高嶺清麿 speaks to his concerned mother.

- yakamashii'!!!

やかましいっ!!!

[You're] noisy!!!

[Stop annoying me!!!] - ore-sama ga, nande anna {tei-reberu na} yatsura to tomodachi ni nan'nakya ikenee-n-da yo'!!?

オレ様が、なんであんな低レベルな奴らと友達になんなきゃいけねーんだよっ!!?

Why do I have to become friends with {low-level} guys like those!!?- tomodachi ni naru

友だちになる

To become friends.

- tomodachi ni naru

A girl that uses ore 俺 is called:

- orekko

オレっ娘

"ore girl."

In general, girls don't use ore.

A girl may grow up surrounded by brothers who use ore and end up copying them, using the pronoun ore herself. This is something a tomboy would do. But normally you'd expect her to change to a pronoun befitting of her gender eventually, as she grows up and changes environment.

The pronoun ore was originally gender neutral, but nowadays it's used only by men, at least in most regions of Japan.

There are some regions that still have the original usage, and as such it isn't weird, in those regions, for girls to use ore.

In anime, a natal female character using a masculine pronoun doesn't necessarily mean they're a transgender man.

Female characters that use ore do tend to also be designed to look like guys a lot, for one reason or another, but often that's just a quirk, the character is a tomboy, or it's part of some weird plot.

- In Minami-ke みなみけ, Minami Touma 南冬馬 uses ore, and, despite being an older and female, she pretends to be the younger brother of Minami Chiaki 南千秋.

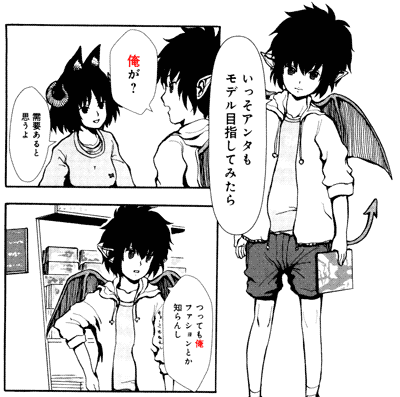

- Context: Gokuraku Nozomi 獄楽希, a monster girl that looks like a boy, checks a fashion magazine that seems to feature one of her friends in the cover.

- isso anta mo moderu φ mezashite-mitara

いっそアンタもモデル目指してみたら

How about [you] try to become a model, too?

- ~te-mitara - ~tara ~たら form of ~te-miru ~てみる, "to try to."

- ore ga?

俺が?

Me? - juyou aru to omou yo

需要あると思うよ

[I] think there's demand.- For a model that looks like a boy.

- tsuttemo ore fashon toka shiran shi

つっても俺ファションとか知らんし

[Even if you say that], I don't know [anything about] fashion.- tsuttemo - contraction of to-itte mo と言っても.

Spelling-wise, ore 俺 is the normal way to spell this pronoun, while ore オレ tends to put emphasis on extroverted connotations rather than on the masculine meaning of word. The spelling ore おれ is sometimes used to denote an accent.

A series with ore in the title is likely to feature a male protagonist.

- {Ore wo Suki na} no wa Omae Dake ka yo

俺を好きなのはお前だけかよ

The One [that] {Likes Me} is Only You?! - Ore Monogatari!!

俺物語!!

I Story. - {Ore no Imouto ga Konna ni Kawaii} Wake ga Nai

俺の妹がこんなに可愛いわけがない

There's No Way {My Little Sister is This Cute}. - Yahari Ore no Seishun Rabukome wa Machigatteiru

やはり俺の青春ラブコメはまちがっている

As I Thought, My Teenager Love Comedy is Wrong. - Ore, Twintail ni Narimasu

俺、ツインテールになります。

I'll Become Twintail. - Kyou Kara Ore wa!!

今日から俺は!!

From today on I... - Mahou Shoujo Ore

魔法少女俺

Magical Girl: Ore.- A series about a girl who magically transforms into a man to fight monsters, and she literally calls herself "Ore" when in this male form.

Boku 僕

The pronoun boku 僕 is a humble first person pronoun typically associated with young boys.

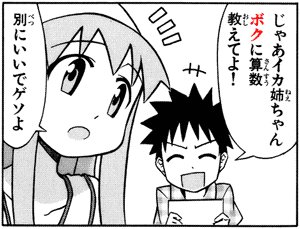

- Context: a young boy asks a squid girl for help with his studies.

- jaa Ika-neechan, boku ni sansuu oshiete yo!

じゃあイカ姉ちゃん ボクに算数教えてよ!

Then, Ika-neechan, teach me arithmetic!- neechan - older sister, may also be used toward young women whom one's not related to, specially used by children toward any girl older than them.

- betsu ni ii degeso yo

別にいいでゲソよ

[I don't mind doing it].

Normally, a boy will start using boku because his parents told him to, and he'll start using ore because he saw his older brothers, or male friends using ore. From young age, the boy will figure he has to use one pronoun in front of his friends, and a different pronoun in front of his parents.

Some parents would rather their little boy didn't use ore, as that's a pronoun men use, and the kid isn't a man yet, others don't mind, either way, eventually the boy grows up to a point using ore is expected, and boku starts sounding too infantile.

Given the above, it makes sense to think that a boy that spends more time in his home, with his family, will use boku more, and a boy that spends more time outside, playing with friends and other external possibly bad influences, will use ore more.

In anime, a boy that uses ore is often extroverted, confident, and strong, maybe due to playing and fighting a lot, while a boy that uses boku is often introverted, timid, and smart, maybe due to reading a lot.

Many series will have the protagonist and his best friend or rival have opposite personalities. Since these two pronouns imply opposite personalities, too, it's not unusual for each to have a different pronoun.

Typically, the protagonist of the series is the confident one, so he uses ore, and his best friend uses boku.

It's not unusual for the boku character to be a bullied pushover who gets saved by the ore character that gradually gives him confidence, or for the ore character to be an unruly kid who hates studying who learns diligence from a boku character.

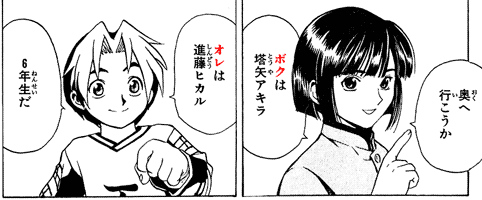

- Context: the rival and the protagonist, both 11 years old, introduce themselves to each other.

- oku e ikou ka

奥へ行こうか

[How about we] go further inside?

- oku - inner part, in this case of a go parlor, as opposed to standing by the entrance.

- ikou - volitional form of iku 行く, "to go."

- boku wa Touya Akira

ボクは塔矢アキラ

I'm Touya Akira. - ore wa Shindou Hikaru

オレは進藤ヒカル

I'm Shindou Hikaru. - roku-nen sei da

6年生だ

[I] am a sixth year student.

- In this case the 6th grade of an "elementary school," shougakkou 小学校.

If the protagonist of a series uses boku, it's likely they lack confidence and the plot is about growth.

At its extreme, a character that uses boku lived a sheltered life, growing up in a family with strict rules, which is probably a rich, traditional one, while a character that uses ore grew up in the streets, or with parents that didn't care much where he was or what he was doing all the time.

- Context: Iida Tenya 飯田天哉 slips and uses boku 僕 as first person pronoun, hinting his upbringing that he had been trying to hide by forcing himself to use ore 俺 instead.

- "boku"...!!

「僕」・・・!!

"boku"...!!! (the other characters repeat what Iida said.) - chotto omotteta kedo Iida-kun te bocchan!?

ちょっと思ってたけど飯田くんて坊っちゃん!?

[I] had thought it a little but: Iida-kun, [you] are a rich boy!?- omotteta - contraction of omotte-ita 思っていた.

- te て - same as the tte って particle, the topic marker tte って in this case.

- bo'!!!

坊!!!

Male mascot characters, targeted at children, typically use boku, too, since the idea is that the mascot is a boy. Such mascots also typically take the ~kun ~君 honorific after their names, which is also used with boys.

Despite its association with children, adult men can use boku, too.

- boku wa Raion

僕はライオン

I'm Lion. - goku futsuu no sarariiman desu

ごく普通のサラリーマンです

[I'm] a very normal salaryman. - gyaa' raion kowaiiiaaaaa

ギャーッライオン怖いいいあああああ

*shriek* a lion, scaryyyyyyaaahhh.

The pronoun boku is softer compared to ore, and ore is more antagonistic, arrogant, compared to boku, as such, some men may prefer to use boku to sound more approachable, kind, or gentle.(mynavi.jp)

In anime, adult men that use boku are often total pushovers, unreliable and weak.

If they are not, then they're merely quiet. They lay low, so they avoid an antagonistic pronoun such as ore. Often, they aren't just quiet, they're quiet and calculating, which probably means they're some sort of psychopath.

- In MONSTER モンスター, the monster uses boku, speaks softly, smiles softly, and murders people.

In spite of being masculine, boku is acceptable when talking to one's superiors due to its humble nuance.

Originally, boku meant "manservant," geboku 下僕, so it has submissive connotations.(日本国語大辞典)

Then the word boku began being used as a way to call out a "boy," and eventually it became used by those boys as pronoun.

Note, however, that just because someone uses boku as pronoun that doesn't mean they'd like to be called a boku.

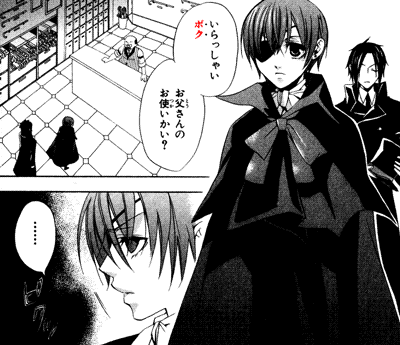

- Context: Ciel Phantomhive シエル・ファントムハイヴ, a 12 year old boy whose first person pronoun is boku, gets annoyed when called boku by a shopkeeper, mostly because his parents are dead, he decided to become the head of the Phantomhive family, and as such he doesn't want to be treated like a kid.

- irasshai boku, otousan no otsukai kai?

いらっしゃいボク お父さんのお使いかい?

Welcome, boy, is [it] [your] father's errand? (literally.)- Are you here doing an errand for your father?

- bouten 傍点 - the dots on the furigana besides the word boku ボク, used to indicate emphasis, like bold text in English. In this case, the emphasis is due to Ciel taking offense on the word boku specifically.

- piku'

ピクッ

*twitch* (with irritation, in this case.)

A girl that uses boku is called:

- bokukko

ボクっ娘

"boku girl."

Once again, this is something that mostly only exists in anime, not in real life, and its purpose is nothing more than a quirk, and carries no deeper meaning to it.

- In Darling in The FranXX ダーリン・イン・ザ・フランキス, Zero Two ゼロツー uses boku.

- In DanMachi ダンまち, Hestia ヘスティア uses boku.

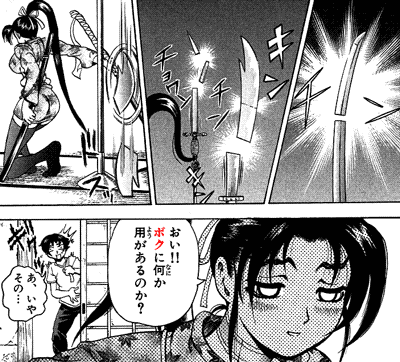

- Context: Kousaka Shigure 香坂しぐれ, a ninja-esque swords and weapons master, practices the fine art of cutting blades with a blade.

- chi, kin, chin, kyoun, kin

チン キン チン キョウン キン

*sound effect of blades being cut.* - dosu'

ドスッ

*sound effect for blade falling in the tatami floor.* - oi!! boku ni nani ka you ga aru no ka?

おい!!ボクに何か用があるのか?

Hey!! Do [you] have any business with me? - giku'

ギクッ

*gulp* - a, iya, sono...

あ、いや その・・・

Ah, erm, that is...- All these three words are interjections.

There are more bokukko in anime than orekko, simply because ore sounds too masculine for the average female character to use.

This is also evidenced in otokonoko 男の娘 characters, boys that look like girls. Such characters are designed to not appear masculine, and they often use boku as pronoun, though that's partially because they tend to be timid, as that's not a masculine trait.

- In Fate, Astoflo アストルフォ uses boku.

- In Steins;Gate, Urushibara Ruka 漆原るか uses boku.

- In Blend S ブレンド・S, Kanzaki Hideri 神崎ひでり is a boy who canonically thinks God has made him cute so he has to share his cuteness with the world by becoming an idol, and, for that purpose, he crossdresses and acts cutely, using boku while in character. Sometimes, he breaks character, speaking like a boy, in lower pitch, and using ore as pronoun instead. This means his actual pronoun is ore, and he deliberately uses boku to appear cuter.

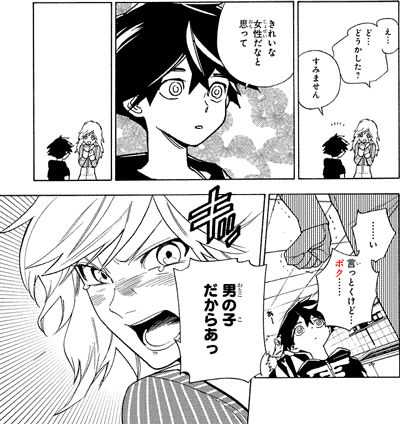

- Context: Kusaka Kabane 日下夏羽 gives his first impressions about Iwa-ki-yama-yuki-sato-shiro-na-no-go-juu-roku-shi Akira 岩木山雪里白那之五十六子晶.

- e... do... douka shita?

え・・・ど・・・どうかした?

Eh... [is something wrong]? - sumimasen

すみません

Sorry. - {{kirei na} josei da na} to omotte

きれいな女性だなと思って

[I was just] thinking "{[what] a {pretty} girl}."- You are.

- ......i, ittoku kedo... boku...... {otoko no} ko dakaraa'

・・・・・・い 言っとくけど・・・ボク・・・・・・男の子だからあっ

......[f, for your information]... I... am a boy!- ittoku - contraction of itte-oku 行っておく, "to say [something] in advance," in this case, so you don't make the same mistake again.

In songs, sometimes a female singer uses boku simply because the pronoun fits the melody better, and the melody was composed before the lyrics. Female artists that write the lyrics first and then compose the melody tend to use boku less.(ongakunojouhou.com)

Spelling-wise, boku 僕 is normally used, and used with quiet, reserved, calm characters. The spelling boku ボク tends to be used with younger characters, and with girls, in order to strip the original "boy" meaning of the word. The spelling boku ぼく is sometimes used with a very small child.

Series with boku in the title feature a male protagonist, sometimes because the series is about growth, other times because the protagonist is a little boy, and other times because the protagonist introverted, or smart, or something like that. It varies.

- {Boku Dake ga Inai} Machi

僕だけがいない街

The Town [in Which] {Only I'm Missing}.- A series about a man who travels back in time, becoming a boy again.

- Bokurano

ぼくらの

Ours.- A series about children fighting in a super robot that's theirs.

- Boku no Hiiroo Akademia

僕のヒーローアカデミア

My Hero Academia- A series about a main character that lacks power, gaining it and building confidence.

- Boku wa Tomodachi ga Sukunai

僕は友達が少ない

I Have Few Friends- Self-explanatory.

- Boku-tachi wa Benkyou ga Dekinai

ぼくたちは勉強ができない

We Can't Study.- A series about a main character studies, i.e. a nerd character, and who has to teach a bunch of other characters that don't know how to study.

Own Name

Using one's own name as first person pronoun is something that toddlers and young girls do.(西川, 1996:147)

- Context: Koiwai Yotsuba 小岩井四葉 tries to catch a cicada.

- totaaa~~!!

とったぁー!!

[I] caught [it]!! - {Yotsuba ga totta} semi da!!

よつばがとったセミだ!!

[This] is a cicada [that] {Yotsuba caught}!!

- In other words:

- {watashi ga totta} semi da

私が捕った蝉だ

[This] is the cicada [that] {I caught}.

Presumably, this is due to parents referring to their children by name, and them not knowing any pronouns, so as far as the toddler is concerned, their name is the only way to refer to themselves.

Boys have to figure out the nuances of ore and boku from young age, so they stop using their names as first person pronoun quicker than girls.

Girls don't switch to watashi until they move to an environment that demands formality. Would that be grade school, middle school, or high school? It varies from person to person.

- Context: Akaza Akari 赤座あかり, a 13 years old girl, regrets not being 14 years old like her friends, because they started middle school one year before her, so she spent a whole year without going to school with them.

- aaa...

あーあ・・・

Aah... (sigh.) - Akari ga {mou ichinen hayaku} umaretetara dougakunen datta noni

あかりがもう一年早く生まれてたら同学生だったのに

If Akari had been born {one year sooner} [we] would have been in the same year of school.

- umaretetara - contraction of umarete-itara 生まれていたら.

- umaretetara - contraction of umarete-itara 生まれていたら.

- Akaza Akari (juu-san)

赤座あかり(13)

Akaza Akari (thirteen).- In Japanese, a number inside parentheses after someone's name typically indicates their age.

- The family name (Akaza) comes before the given name (Akari), opposite to the name ordering in America, for example.

Using your own name as first person pronoun sounds childish, silly, or cutesy. Sometimes this includes the diminutive suffix ~chan ~ちゃん, which is also cutesy.

Characters that use their own name as pronoun, or a nickname, tend to sound more infantile, and sometimes more stupid, than other characters.

- In Steins;Gate, Shiina Mayuri 椎名まゆり uses Mayushii まゆしぃ as first person pronoun, which is a cutesy nickname for herself.

- In Re:Zero, Felix Argyle フェリックス・アーガイル, a cat boy that looks like a cat girl, uses Feri-chan フェリちゃん as first person pronoun.

Note that when one's name comes after the demonstrative kono この, "this," that's a completely different thing that's not childish at all. In this case, it's used emphasizes you're talking specially about yourself, and it's often used by characters who are full of themselves.

- Context: Nappa ナッパ talks to Kakarot カカロット.

- {temee nanka ga

kono Nappa-sama ni

kanau} wake ga nai-n-da!!!

てめえなんかがこのナッパさまにかなうわけがないんだ!!!

[There's no way] {[someone like] you [can defeat] THIS NAPPA-SAMA}!!!- kanau 叶う - means "to rival" sometimes, as in, "can defeat," since someone unrivaled is undefeatable.

Relative Title

In some cases, a person can refer to themselves by a title that describes their relationship with whom whom they're talking with.

For example, just like students can refer to their teacher by the word "teacher," sensei 先生, the teacher also refer to themselves by that word. This only makes sense when the teacher is talking to their students, however, since the sensei for them is teacher.

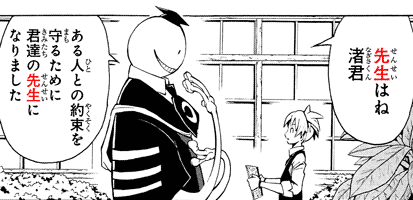

- Context: Koro-sensei 殺せんせー, a teacher, talks to Shiota Nagisa 潮田渚, one of his students.

- sensei wa ne, Nagisa-kun

先生はね 渚君

Nagisa-kun, [about me], [you see]- In this line, the speaker is the teacher, the sensei.

- When he talks "about the sensei," he's talking about himself: "about me."

- {aru hito to no yakusoku wo

mamoru} tame ni

kimi-tachi no sensei ni

narimashita

ある人との約束を守るために君達の先生になりました

In order to keep a promise with a [certain] person {[I've] become your teacher}.

When immediate family talks to toddlers, they'll call themselves by their relative title, too. For example, the "father" will call himself papa パパ, the "mother," mama ママ, and so on. They'll also call each other by a title relative to the child, so "mother" can also mean one's "wife" in some cases.

- Context: Kusuo's father, Kuniharu 國春, and mother, Kurumi 久留美, had had a fight and were living in separate rooms. Now, they're back together, so Kuniharu asks Kusuo, who has the power of psychokinesis, to carry the furniture from his room to Kurumi's room, saying that he can't do it himself because he'll be busy carrying something else.

- hora... boku wa {mama wo hakobu} no de sei-ippai dakara ne...

ほら・・・僕はママを運ぶので精一杯だからね・・・

Look... [it takes my all just] {to carry mom}, [you see]...- Mom = my son's mom = my wife.

- sei-ippai

精一杯

Taking all of one's efforts.

- takumashii wa, papa...

たくましいわ、パパ・・・

[You're so] strong, dad...- Dad = my son's dad = my husband.

- mou ichido iu zo, jibun de hakobe

もう一度言うぞ、自分で運べ

[I] will say [it] again, carry [it] yourself.

Watakushi ワタクシ

The pronoun watakushi ワタクシ is a stiffer variant of watashi, or rather, the original word is watakushi, and watashi is an easier way to pronounce it.

Both words can be spelled with the same kanji, as 私. There's no way to tell them apart without furigana, so sometimes watakushi is spelled with katakana instead to disambiguate.

Using watakushi often sounds too formal, since watashi suffices, and there's no need to use watakushi.

In anime, characters that use watakushi tend to be rich and classy, or serve rich and classy people.

This includes maid and butler characters, and the "rich girl," ojousama お嬢様, characters whom they server. Another piece of yakuwarigo used by ojousama characters is ending their sentences with the wa わ particle, like desu wa and ~masu wa.

Atashi あたし

The pronoun atashi あたし is an informal variant of watashi that's typically used by women and effeminate men.

Women that use atashi will switch to watashi in business contexts, just like men who use ore.

It's only acceptable for men to use watashi due to formality, otherwise it's feminine. Since atashi removes the formality, you end up with just a feminine pronoun.

In anime, effeminate, gay men, i.e. okama オカマ characters, may use atashi as pronoun. This is an example of onee-kotoba オネェ言葉.

See: female language for details.

- In "Black Butler," Kuroshitsuji 黒執事, Grell Sutcliff グレル・サトクリフ uses atashi as first person pronoun, as well as other feminine language, like the ~wa ~わ sentence ending particle.

This word can be spelled 私, too.

Jibun 自分

The pronoun jibun 自分 is associated with military officers, police men, detectives, professions that follow a strict rules, and where knowing your place in the hierarchy is fundamental.

The pronoun is used, for example, to introduce yourself to an organization, in job interviews, as it emphasizes that you're a diligent person who will respect the organization structure.

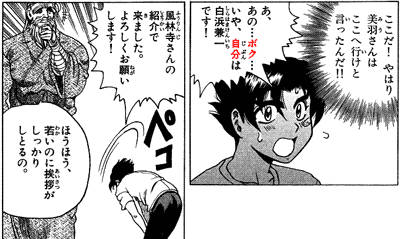

- Context: Ken'ichi greets a martial arts master.

- koko da! yahari Miu-san wa {koko e ike} to itta-n-da!!

ここだ!やはり美海さんはここへ行けと言ったんだ!!

[It] is here! [As I thought], Miu-san told [me] {to go here}!! - a, ano... boku... iya, jibun wa Shirahama Ken'ichi desu!

あ、あの・・・ボク・・・いや、自分は白浜兼一です!

E, erm... I(boku), [I mean], I(jibun) am Shirahama Ken'ichi.- jibun - a pronoun typically associated with military officers, police officers, detectives, and the sort of profession that demands strict conduct and knowing one's place in a hierarchy.

- Fuurinji-san no shoukai de kimashita. yoroshiku onegai shimasu!

風林寺さんの紹介で来ました。よろしくお願いします!

[I] came by Fuurinji-san's invitation. [I'll be in your care]!- yoroshiku onegai shimasu - expression used when introducing yourself, take good care of me, I'll be in your care, pleased to meet you, etc.

- peko

ペコ

*bows* - houhou, {wakai} noni aisatsu ga shikkari shitoru no.

ほおほお、若いのに挨拶がしっかりしとるの。

Ho ho, despite {young} [you] greet properly. (literally.)- i.e. you know your manners for someone of your age.

Some men use jibun as their preferred pronoun, usually because of the diligent nuance it has.

The word jibun 自分 also means "oneself," as in:

- jibun no namae

自分の名前.

One's own name.- ichininshou wa jibun no namae

一人称は自分の名前

[Their] way to refer to first person is one's own name. (literally.)

They refer to themselves by their own name.

They use their own name as first person "pronoun."

- ichininshou wa jibun no namae

- Context: Masa 雅 asks Tatsu たつ for help in a fight, who responds:

- jibun de utta kenka yaro

自分で売った喧嘩やろ

That's a fight [you] picked yourself, [wasn't it]!- kenka wo uru

喧嘩を売る

To sell a fight. (literally.)

To pick a fight with someone.

- kenka wo uru

- {jibun de kata-tsuke-n}-no ga suji chau-n-ka!

自分で片つけんのが筋ちゃうんか!

{To clear [your mess] yourself} [is only logical], [am I wrong]?- kata-tsuke-n-no - contraction of kata-tsukeru no 片つけるの.

- suji - reason, logic, besides other meanings, can be used to refer to something that you're supposed or expected to do in response to something else because it's the reasonable thing.

- chau-n-ka - contraction of chau no ka.

- chau - Kansai dialect, equivalent to chigau 違う, "to differ," "to be wrong about something."

- Do it yourself!!

Do it yourself!!

Washi ワシ

The pronoun washi ワシ is typically associated with elderly men. It's also spelled 儂, わし.

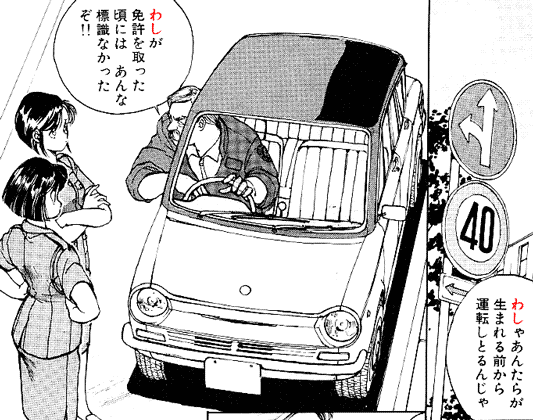

- Context: an old man gets stopped by a couple of policewomen for not obeying a traffic sign.

- washa {anta-ra ga umareru} mae kara unten shitoru-n-ja

わしゃあんたらが生まれる前から運転しとるんじゃ

I have been driving since {before you [two] were born}.- washa わしゃ - a contraction of washi wa わしは.

- shitoru - a contraction of shite-oru しておる, in this case synonymous with shite-iru している.

- ja じゃ - same as the da だ copula, typically used by old men.

- {washi ga menkyo wo totta} koro niwa anna hyoushiki φ nakatta zo!!

わしが免許を取った頃には あんな標識なかったぞ!!

When {I took [my] license} that [traffic] sign didn't exist!!

In the Kansai 関西 region, washi is also used by younger men instead of ore 俺.

In anime and games, specially medieval adventure JRPGs inspired by dragon quest, isekai 異世界 anime, you'll have old, white-haired king handing out quests to a hero, and that king absolutely will use washi.

Centuries old sorcerers, wizards, sages, etc., also often use washi.

Other yakuwarigo for old men include ending one's sentences with ~ja ~じゃ, ~nou ~のぅ, ~jatta ~じゃった, and so on.

In some cases, a young character using this language that's completely unexpected of them is an example of gap moe.

- In Baka to Test to Shoukanjuu バカとテストと召喚獣, Kinoshita Hideyoshi 木下秀吉, a high school student, uses washi, ~ja, ~nou, etc.

Uchi うち

The pronoun uchi うち is typically associated with girls from Kansai 関西, although the pronoun is also used in other regions, and in some regions even boys use it.

The pronoun comes from uchi 内, which means "inside," or "within" in the sense of while something is true.

- te no uchi ni aru

手の内にある

[It] is at [my] hand's inside. (literally.)

It's inside of my hand. - {samenai} uchi ni nomu

冷めないうちに飲む

To drink [it] within the time [which] {[it] doesn't cool}. (literally.)

To drink [it] before {[it] cools}.

To drink [it] while {[it] is hot}.

The antonym is soto 外, "outer," "outside."

The word can also refer to one's family, "household," uchi 家.

- uchi no musume

うちの娘

My daughter. (e.g. as uttered by a father.) - uchi niwa terebi ga nai

家にはテレビがない

In [my] house, there's no TV.

It's only implicit that it means "[my] house." If prefixed by o~ お~, it's implicitly "your" house instead.

- o-uchi wa doko desu ka?

お家はどこですか

Where is [your] house?

The phrase no uchi のうち, "house of," is sometimes contracted to ~n-chi んち.

- ore-n-chi, or ore no uchi

俺んち, 俺のうち

My home. My house. My household. My family. - Kobayashi-san Chi no Meidoragon

小林さんちのメイドラゴン

The Maidragon of Kobayashi-san's Household.

Ware 我

The pronoun ware 我 emphasizes one's very existence. It's a rather literary pronoun, and it's not used normally, although it does show up in a number of set phrases.

- ware nagara

我ながら

While [it] is myself. (literally.)

Even if I say so myself.- Used when praising your own actions.

- *bakes a cake*

- ware nagara oishii

我ながら美味しい

[It] is delicious, even if I say so myself. - *looks at your own clone*

- ware nagara utsukushii

我ながら美しい

[I] am beautiful, even if I say so myself.

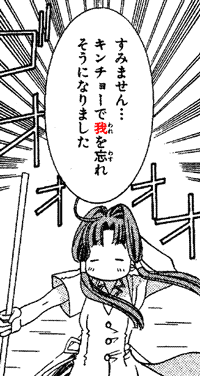

- Context: Mizunashi Akari 水無灯里, a wannabe gondolier, gets nervous rowing a boat for the first time, rowing too fast until the passenger tells her to slow down.

- sumimasen...

すみません・・・

Sorry... - kinchou de {ware wo wasure-sou ni} narimashita

キンチョーで我を忘れそうになりました

[I] became`{close to forgetting myself} due to nervousness. (literally.)- ware wo wasureru

我を忘れる

To forget oneself.

To be so focused in doing a task that you forget your own existence, in the sense of doing only one thing and forgetting about your surroundings (the passenger), or a greater objective.

- ware wo wasureru

Characters that use ware 我 tend to not have physical body, or have transcended it somehow, referring to themselves as a conscious existence instead.

Waga 我が

The pronoun waga 我が, also spelled waga 我ヶ, is a possessive variant of ware 我, sharing the same base wa わ morpheme. The ga が is an archaic possessive function of the ga が particle. An archaic variant of waga is aga 吾.

- aga kimi

吾君

My lord. - waga kimi

我が君

This pronoun, too, is limited in usage, and it's generally literary.

It's typically used to refer to something or someone related to oneself. For example:

- waga kuni

我が国

My country. - waga kou

我が校

My school. - waga tomo

我が友

My friend. - waga sha

我が社

My company. (in the sense of the business I represent.) - waga ya

我が家

My home. My family. - waga na wa Megumin! {aaku-wizaado wo nariwashi to shi, saikyou no kougeki mahou "bakuretsu mahou" wo ayatsuru} mono!

我が名はめぐみん! アークウィザードを生業とし、最強の攻撃魔法“爆裂魔法”を操る者!

My name is Megumin! The one [who] {makes arch-wizard [her] profession, and commands the most powerful offensive magic, explosion magic}!- shi - ren'youkei 連用形 of suru する.

- X wo Y to suru

〇〇を〇〇とする

To make X Y.

The pronoun can also mean "one's own," rather than being used as a first person pronoun.

- Aburahamu wa waga ko wo ikenie ni sasageta

アブラハムは我が子を生贄に捧げた

Abraham gave his own child as a sacrifice.

Exceptionally, waga-mama わがまま, "one's own way," is used as a single adjective meaning "egoist."

See mama まま for details.

Wareware 我々

The pronoun wareware 我々 is a reduplication of ware 我, which works as a plural.

- 々 - an iteration mark that repeats the previous kanji.

Just like ware, wareware has very limited actual usage. It typically refers to one's party, like the organization they represent, or "we," as "us, members of" something. At its extreme, it can refer to all members of your species.

- Context: a wild UFO appears.

- wareware wa uchuujin desu

我々は宇宙人です

We are aliens.

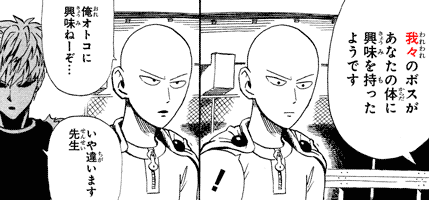

- Context: a caped baldy with extreme strength is targeted by an evil organization. He interrogates one the bad guys concerning why they're after him.

- {wareware no bosu ga

anata no karada ni

kyoumi wo motta}

you desu

我々のボスがあなたの体に興味を持ったようです

It seems {our boss had interest in your body}. - !

- ore, otoko ni kyoumi nee zo...

俺オトコに興味ねーぞ・・・

I don't have interest in men... - iya, chigaimasu, sensei

いや違います先生

No, [you got it wrong], master.- They aren't "interested" as in "attracted," they are "interested" in why he's so physically powerful.

The possessive of wareware is wareware no 我々の.

Wagahai 我輩

The pronoun wagahai 我輩, 我が輩 or 吾輩, is a literary, grandiose sounding pronoun that's basically only used by a character that doesn't have slightest hint of common sense.

Such characters tend to come from completely different eras, or completely different worlds, or are monsters, or inhuman beings like that.

- In Majin Tantei Nougami Neuro 魔人探偵 脳噛ネウロ, Neuro, a creature from the underworld, refers to himself as wagahai when talking to his human

slaveaccomplice, but uses boku when talking to humans that don't know of his true identity.

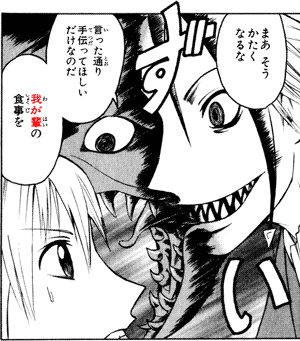

- Context: Nougami Neuro 脳噛ネウロ

threatenscalms Katsuragi Yako 桂木弥子. - maa, sou kataku naru na

まあ そうかたくなるな

[Now, don't become so nervous].- katai

かたい

Solid. Hard. Stiff.

Formal. Uncomfortable. Nervous.

- katai

- {itta} toori te-tsudatte hoshii dake nanoda

言った通り手伝ってほしいだけなのだ

As [I] {said}, all [I] want is for [you] to help [me]. - waga-hai no shokuji wo

我が輩の食事を

With my meal.- X wo te-tsudau

〇〇を手伝う

To help with X. - In this series, Neuro eats mysteries, so his "meal" is a mystery, literally.

- X wo te-tsudau

- Context: just... just focus on the dialogue, okay?

- boku wa joshu desu!!!

僕は助手です!!

I'm an assistant!! - kono meitantei

Katsuragi Yako-sensei no!!

この名探偵桂木弥子先生の!!

Of this famous detective, Katsuragi Yoko-sensei!!

- sensei 先生 - teacher, also used toward a master of a craft.

- The dots on the furigana of 名探偵 express emphasis.

Sometimes, it's used in reference to the 1905 novel Wagahai wa Neko de aru 吾輩は猫である, "I'm a cat."

- In 「K」, Neko ネコ, a cat girl, uses wagahai.

The word wagahai has the same "comrade" morpheme as kouhai 後輩, "junior," senpai 先輩, "senior," and douhai 同輩, "one's equals." In other words, literally, wagahai means "my brethren," my nakama 仲間, or something like that.

Onore 己

The pronoun onore 己 means "self," and can sometimes be used as first and second person pronoun.

- {onore no shita} koto

己のしたこと

The thing [that] {one did}.

What you have done.

What I have done. - teki wo shiri, onore wo shireba, hyakusen ayaukarazu

敵を知り己を知らば百戦危うからず

Knowing thy enemy, and knowing thyself, fear not a hundred battles.- A Japanese translation of The Art of War, meaning that if you know your enemy's abilities, and your own, you'll never be uncertain about the outcome of a battle.

The word onore rarely means "I," however, most of the time it means "you," or "one," and it's also translated to "damn you," when used alone: onore!

A variant of onore is unu うぬ, which is sometimes used as pronoun, too.

Kochira こちら

The pronoun kochira こちら means "this way," or "this side," and can refer to one's own party in a negotiation or conversation. Similarly, sochira そちら can mean "you."

Kocchi こっち

The pronoun kocchi こっち is a variant of the more formal kochira, and can be used the same way.

- Context: a class full of delinquents decides to try to find out who's the strongest delinquent around. Kamiyama 神山, who's not a delinquent, was nominated as a possible strongest.

- nande boku ga nomineeto sareteiru-n-desu ka....

なんでボクがノミネートされているんですか・・・・

Why have I been nominated....? - baka yarou

バカヤロウ

[You] idiot. - kocchi no serifu da!!

コッチのセリフだ!!

[It] is my side's line!!

I should be asking that, not you.

I also have no idea, and I want to know, too! - sassato sagaranee to bukkorosu zo!!

さっさと下がらねえとブッ殺すぞ!!

If [you] don't withdraw immediately [I'll] murder [you]!!

Atakushi あたくし

The pronoun atakushi あたくし is a mixture of atashi and watakushi, that is, it's female, classy pronoun.

This pronoun is rarely used in real life, though it's sometimes used in fiction by rich, female characters, or by pompous, extra formal female characters.

- In Ace Attorney, Gyakuten Saiban 逆転裁判, Ayasato Kimiko 綾里キミ子 uses atakushi, and speaks in a dialect featuring u-onbin ウ音便.

Atai あたい

The pronoun atai あたい is a variant of atashi used by women during the Edo period (1603–1868). It's an example of Edo-kotoba 江戸言葉.

Nowadays, it's rarely used besides in fiction.

Oira おいら

The pronoun oira おいら, or オイラ, comes from ore-ra 俺等 or onore-ra 己等, both of which are plural, but is confusingly used as a singular first person pronoun.

When oira is a variant of onore-ra, it can also be used as second person pronoun, but this rarely happens.

Normally, instead, oira comes from ore, making it a masculine pronoun.

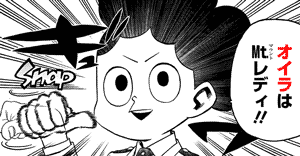

- Context: characters are asked what's their favorite hero, Mineta Minoru 峰田実 answers:

- oira wa

Mt. (maunto) Redhi!!

オイラはMt.(マウント)レディ!!

For me, [it's] Mt. Lady!! (correct.)

Ora おら

The pronoun ora おら, or オラ, is another variant of ore 俺, used by men from Chūbu 中部, the "central region" of Japan, which lies to the west of Kantou.

- In Dragon Ball ドラゴンボール, Goku 悟空 uses ora.

The word ora オラ is also used to call someone's attention, like "hey," and it's notoriously used as ora ora ora オラオラオラ in JoJo's Bizarre Adventure.

Oi おい

The pronoun oi おい is typically used by men from Kyūshū 九州, the Southwestern part of Japan. A variant is oidon おいどん.

Normally, oi おい is a way to call someone else, like "oy," "hey," etc. Confusingly, this pronoun has nothing to do with oira おいら.

Sessha 拙者

The pronoun sessha 拙者 is a humble pronoun used by warriors, samurai 侍. Since these warriors are male, sessha ends up being a masculine pronoun, too.

It's also used by nerds, otaku オタク characters, who speak mimicking such warriors.

The copula degozaru でござる is a yakuwarigo for samurai and the samurai-copying otaku characters.

- Context: Kiriu Doushirou 桐柳道士郎 was born in Japan but raised in Nevada, U.S.A., as a Japanese samurai, who likes having honorable battles and stuff like that, except that:

- sessha φ, {dare to demo shoubu suru} wake dewa gozaran.

拙者、誰とでも勝負するわけではござらん。

It's not like I {will compete with [just] anybody}.- shoubu - to compete against, to have a battle with, to fight with.

- dewa gozaran - archaism, same meaning as dewa gozaimasen ではございません.

- kuzu-domo towa sen no da.

クズ共とはせんのだ。

[I] don't do [it] with scum.- In other words, Doushirou only competes with honorable people, against scum he just beats them up.

- sen せん - contraction of senu せぬ, archaism for shinai しない, negative form of suru する.

Yo 余

The pronoun yo 余, or 予, is an archaic pronoun used like ware, as such, nobody uses this nowadays except for grandiose-sounding characters that are thousands of years old.

- Context: Yoshida Yuuko 吉田優子, who recently grew horns and found out she's a demon girl, meets her ancestor in a dream.

- yo wa onushi no sosen!!

余はおぬしの先祖!!

I'm your ancestor! - yami no ichizoku no shiso da!!

闇の一族の始祖だ!!

The founder of the darkness clan!! - {anta ga sono sugata ni natta} hi ni ippen atta darou!

あんたがその姿になった日にいっぺん会っただろう!

We've met on the day {you became in that form (with horns)}, [haven't we]?! - yume no naka de!!

夢の中で!!

Inside a dream!! - gosenzo-sama...?

ごせんぞさま・・・?

Ancestor...? - dai-ichi-wa boutou sankou

第一話 冒頭 参照

Consult: First Chapter, Beginning. (where they first met in a dream.)

Originally, these kanji could also be read as ware 余.

The word yohai 余輩 is variant of this pronoun, just like wagahai is a variant of ware.

Other Pronouns

There are countless other words that can be used as first person pronoun in Japanese, specially in fiction.

Some of them are even made up.

- In Osomatsu-san おそ松さん, Iyami イヤミ, who insists he's actually French, uses mii ミー as first person pronoun, which probably comes from "me" in English.

References

- 西川由紀子, 1996, November. 発達 14-PB3 子どもの使用する一人称の変化. In 日本教育心理学会総会発表論文集 第 38 回総会発表論文集 (p. 147). 一般社団法人 日本教育心理学会.

- 山本雅子, 2005. テイル形式の認知的意味. 言語と文化, 13, pp.89-101.

- 小畠裕将, 2014. 男性の一人称代名詞の地理的分布:『方言文法全国地図』 を用いて. 論叢国語教育学, (10), pp.49-59.

- 僕 - 精選版 日本国語大辞典 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2021-03-22.

- 一人称は僕、オレ、私? 彼が何を使うかで距離感がわかるかも - woman.mynavi.jp, accessed 2021-03-22.

- 女性アイドル・女性アーティストの歌詞で一人称「僕」が多い理由を分析してみた - ongakunojouhou.com, accessed 2021-03-25.

- 【一人称『わい』とは?】リアルでも自分のことを「ワイ」と呼ぶワイが徹底的に調べてみた - negiyan.me, accessed 2021-04-01.

There should be the caveat that "washi" and "uchi" are more common in the Kansai dialect as first-person pronouns than in standard Japanese. What "atashi" is to Tokyo-ben, "uchi" is for Kansai-ben. "Washi" is used in Kansai dialect by adult men, too (several characters from the Yakuza series: Goro Majima, Futoshi Shimano, Ryuji Goda, Wen Hai Lee and Homare Nishitani); it's just that I've never seen any kids or teens use it.

ReplyDeleteWell done

ReplyDelete