In Japanese, baka バカ, also spelled 馬鹿, ばか, means "stupid" or "idiot." It can mean that someone is stupid, or did something stupid. Or is stupid about something, i.e. fixated on it. That's stupidly high, i.e. absurdly high, extremely so. Or that it became stupid in the sense of it stopped functioning.

Manga: Saiki Kusuo no Psi Nan 斉木楠雄のΨ難 (Chapter 2, 最低Ψ悪!?燃堂力)

Spelling

There are multiple ways to spell the word baka in Japanese.

It's normally written with katakana or with kanji, but it may be spelled with hiragana for aesthetic reasons.

- Baka to Tesuto to Shoukan-juu

バカとテストと召喚獣

Idiots, Tests, and Summoned-Beasts.- The title of this series uses the katakana spelling, for example.

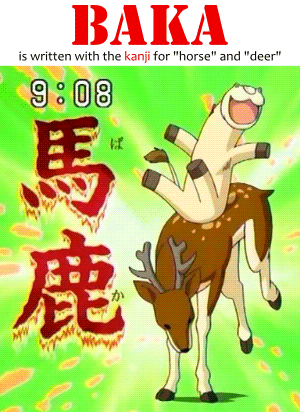

Kanji

The kanji of baka are kanji for words that refer to animals:

- uma

馬

Horse. - shika

鹿

Deer.

Based on the kanji's meanings, you could guess the word baka should mean something about a "horse" and a "deer," right? Horse and deer. Horse deer. A horsey deer. What's that even supposed to mean?

It doesn't mean anything.

Origin

The word baka isn't actually Japanese. It's a loan word, a transliteration of the Sanskrit word "moha," meaning "foolish person"(馬鹿 - デジタル大辞泉).

Sanskrit doesn't have kanji, so some random kanji were selected phonetically to spell the word. This is called an ateji 当て字.

Since the ateji is only concerned with matching the sound, the kanji reading, not the kanji meaning, you often end up with words with nonsensical kanji meanings, which is the case with horse-deer baka.

Specifically, moha has had the following ateji(馬鹿 - gogen-allguide.com, 馬鹿・莫迦・破家 - 精選版 日本国語大辞典):

- bakuka 莫迦

- boka 募何

- moha 莫迦

- haka 破家

- baka 馬鹿

Among these, it seems only the horse-deer one really stuck.

A theory about its origin is that it comes from a Chinese story in which someone points at a deer and says it's a horse. Since that sounds like something pretty stupid to do, people started spelling the word "stupid" as horse-deer(馬鹿 - gogen-allguide.com).

Meaning

The word baka means "stupid" or "idiot" depending on its usage on a sentence, and baka is used in a number of different ways. For example:

- To call someone stupid.

- baka

バカ

[You] [are] stupid.

[You] [are] an idiot. - koitsu wa baka da

こいつはバカだ

This [guy] is an idiot. - baka na no?

バカなの?

Are [you] stupid? - baka janai no?

バカじゃないの?

Aren't [you] stupid? - baka ka omae?

バカかお前?

Are you stupid? - {baka na} oniichan

馬鹿なお兄ちゃん

[My] older brother [that] {is stupid}.

[My] stupid older brother.

A stupid young guy. (a second meaning of oniisan お兄さん.) - {omae-ra ni kiita} ore ga baka datta

お前らに聞いた俺がバカだった

Me [who] {asked you [guys]} is an idiot.

I'm an idiot for asking you guys.

- baka

- To call something stupid, ridiculous.

- To refer to an idiot.

- {baka no iu} koto wo kiite wa ikenai

バカの言うことを聞いてはいけない

[One] should not listen to the things [that] {an idiot says}. - baka-domo

バカども

The idiots. [You] idiots. [These] idiots. (plural.)

- {baka no iu} koto wo kiite wa ikenai

- To refer to being treated like an idiot, mocked.

- baka ni suru

バカにする

To treat [someone] like an idiot.

To mock someone. - baka ni suru na!

バカにするな!

Don't treat [me] like an idiot!

Don't mock [me]! - baka ni shinai de

バカにしないで

- baka ni suru

- To refer to something stupid that one did.

- watashi no baka

私のバカ

[It] [is] my "stupid".

It's my fault. - oniichan no baka!

お兄ちゃんのバカ!

[It] [is] [my] brother's "stupid"!

It's my brother's fault!

- watashi no baka

- To refer to stupidity.

- baka-sa

バカさ

Stupidity. - baka-rashii

馬鹿らしい

Idiotic. Something that feels stupid.

- baka-sa

- To say something has stopped working, lost its function.

- kagi ga baka ni natta

鍵がバカになった

The key became stupid.

The key doesn't open the lock anymore. It stopped working.

- kagi ga baka ni natta

- As a suffix, referring to how stupidly fixated someone is onto something.

- oya-baka

親バカ

"Parent-stupid."

Fixated on being a parent. Pampering one's children. - souji-baka

掃除バカ

"Cleaning-stupid."

Fixated on cleaning one's house.

- oya-baka

- To say something is stupidly high, absurdly highly, exceedingly so.

- baka-shoujiki

馬鹿正直

Absurdly honest. A very honest person. - baka-dikara

馬鹿力

Absurd power. Incredibly strength. - baka-sawagi

馬鹿騒ぎ

Absurd racket. A huge commotion. - baka ni atsui

馬鹿に暑い

Absurdly hot. (weather.)

- baka-shoujiki

A word that sound similar to baka is:

- bakka

ばっか - bakkari

ばっかり - bakari

ばかり

Only. Just.

This word, bakari, is thought to come from hakari 計り, "measurement," the noun form (ren'youkei 連用形) of hakaru 計る, "to measure." Its meaning is "only" or "just," although it's often used to say that someone only (just) does one thing.[ばかり - 精選版 日本国語大辞典 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2020-10-28]

- geemu suru bakari

ゲームするばかり

Just plays games. - geemu suru bakkari

ゲームするばっかり - geemu suru bakka

ゲームするばっか

vs. Aho

Besides baka, there's another word that means "stupid" in Japanese: ahou 阿呆, or just aho アホ. Since they both mean "stupid," they're synonymous, you can replace one by the other and the sentence should mean the same thing.

However, there are a few differences between baka and aho.

Lexically, if you have a word that's made out of either baka or aho and something else, you can't just replace baka by aho or vice-versa, and baka has more uses than aho has. For example:

- ahoge アホ毛, literally "stupid hair," is always aho-ge, never baka-ge. You can't switch aho for baka here.

- baka-shoujiki 馬鹿正直, "stupid-honest," in the sense of "extremely honest," can't be rewritten as aho-shoujiki.

Regionally, a eastern part of Japanese, Kantou 関東, and a western part of Japan, Kansai 関西, regard one word as being more offensive than the other differently.

- In Kantou, baka is more common, so people are used to it, and aho, which is rarer, sounds more offensive.

- In Kansai, aho is more common, so baka is more offensive.

Conjugation

The word baka is a na-adjective. It's not inflectable. Instead, the copula that comes after baka is what gets conjugated.

| shuushikei 終止形 Predicative form. |

baka da バカだ |

|---|---|

| rentaikei 連体形 Attributive form. |

baka na バカな |

| ren'youkei 連用形 Adverbial form. |

baka ni バカに |

| te-kei テ形 te-form. |

baka de バカで |

| teineikei 丁寧系 Polite form. |

baka desu バカです |

Grammar

Since baka バカ is a word that appears so much in anime, I'm going to dedicate this article into explaining how the grammar behind a number of uses of the word work.

- {{baka ni-mo wakaru} you ni} setsumei suru

バカにもわかるように説明する

To explain [it] {so [that] {even an idiot understands}}.- Phrase used when talking about making very easy-to-understand explanations.

- Tarou ni-wa wakaru

太郎にはわかる

To Tarou, [it] is understood.

Tarou understands [it]. - Hanako ni-mo wakaru

花子にもわかる

To Hanako, too, [it] is understood.

Hanako understands [it], too.

Even Hanako understands [it]. - {Hanako ni-mo wakaru} you ni

花子にわかるように

So [that] {even Hanako understands [it]}.

Calling People Stupid

Calling other people stupid in Japanese without knowing Japanese sounds pretty stupid, but most importantly, it's often done wrongly.

People who don't know much about Japanese will be tempted to call other people "stupid" by translating the English sentence "you are stupid" word by word to Japanese.

The first problem is that there are multiple ways to say "you" in Japanese: anata あなた, omae お前, kimi 君, kisama 貴様, etc. But whatever, let's just pick one of them.

The second problem is that there are also multiple way to say "is," "are," in Japanese: da だ, desu です, de aru である, etc. But, again, whatever, let's just pick one of them.

As we've seen before, there are multiple ways to spell baka in Japanese. Let's just pick one of them.

Putting it all together:

- anata wa baka desu

あなたは馬鹿です

You are stupid. - omae wa baka da

お前は馬鹿だ - kimi wa baka desu

君は馬鹿です - kisama wa baka da

貴様は馬鹿だ

And so on.

Although the phrases above are all grammatically correct, you'd sound very stupid trying to call someone stupid in the ways above. This is because of two reasons:

- Using a second person pronoun like anata, omae, etc. is unusual in Japanese.

- The word desu is polite speech. Are you calling people stupid or trying to be polite?

The proper way of calling someone stupid in Japanese would be more like this:

- baka!

馬鹿!

Stupid!

Idiot!

Yes, I know it sounds weird, it's just one word. But that really is the way.

Japanese doesn't have an "it" pronoun. In a phrase like "it is pretty," "it" is the subject, and "is pretty" is the predicate. In Japanese, you only say "is pretty," since there's no "it."

- kirei!

綺麗!

[It] is pretty! - kawaii!

可愛い

[It] is cute!

Just like talking about "it" doesn't require you to say "it," talking about "you," and talking about "me," don't require these pronouns, either.

If you say something like omae wa baka da お前は馬鹿です, it sounds like you're stating a fact, not actually insulting anyone. It sounds like you're saying "you are an idiot" the same way you'd say "you are a shopkeeper."

That happens mostly because the plain predicative copula da だ is generally omitted in speech. Just because you aren't being polite, that doesn't mean you'll be ending your sentences with da だ all the time.

A character known for calling people stupid in this matter-of-fact way is Doraemon:

- kimi wa jitsuni baka da na

きみはじつにばかだな

You are truly stupid, huh.

Besides da だ, the polite desu です and literary de aru である are also copulas that will sound like you're stating a fact rather than swearing at somebody.

- Context: Saiki explains why he can't figure out what Nendou is thinking.

- riyuu wa

sugu wakatta

理由はすぐ分かった

The reason [I] understood immediately. - paaan

ぱーーーん

*ta da!* (sound effect used when something is presented, in this case, Nendou, the character.) - wahihi ahii

わひひ あひー

*idiotic snickering* - kono otoko

baka

nano de aru

この男バカなのである

This man is an idiot.

The copula da だ is required when using conjunctions such as ga が and kedo けど, which mean "but," "however," forming daga だが and dakedo だけど, respectively, and also with kara から, to form "because," dakara だから.

- baka da kedo {ii} yatsu da

バカだけどいいやつだ

[He] is stupid, but [he] is a {good} guy. - kimi wa baka da kara

君はバカだから

Because you're stupid

To tell people they aren't stupid, the negative form is used.

- baka janai

バカじゃない

[They] are not stupid.

I'm Stupid

To say "I'm stupid" in Japanese, a first person pronoun like watashi 私, ore 俺, boku 僕, etc. is necessary.

As mentioned previously, you normally don't need to say the subject when talking about "me" or "you" as it's understood form context.

- daijoubu desu

大丈夫です

[I] am alright. - yatte-miru

やってみる

[I] will try to do [it].

However, baka by itself is normally understood as "[you] are stupid," not "[I] am stupid," so we must be explicit about who's stupid in this case.

- Context: Edward sulks over his ineptitude.

- ore wa baka da

オレはバカだ

I'm stupid. - ano toki kara

sukoshi mo

seichou shichainai

あの時から

少しも

成長しちゃいない

[I] haven't matured even a little since that time. - I.e. Edward did something stupid before, and he feels he didn't learn anything since that time, he hasn't matured, grown up, improved, etc. Nothing changed, and he's doomed to repeat the same mistakes he did in the past. He implies he's an idiot because he hasn't learned from his past mistakes.

A common example of this usage would be:

- {omae-ra ni kiita} ore ga baka datta

お前らに聞いた俺がバカだった

[It] is me [who] {asked you guys} who was stupid.

I was stupid to ask you guys.- baka バカ is an individual-level predicate and as such requires who "is stupid" to be marked as the topic of the sentence by either the wa は particle or the tte って particle.

- When the ga が particle is used instead, topic and focus are reversed due to only the focus-marking function of ga が being available in ILPs(鈴木, 2014:36).

- Observe the difference:

- ore wa baka datta

俺はバカだった

I was stupid.- This sentence is about "me."

- i.e. ore is the topic, baka datta is focus.

- ore ga baka datta

俺がバカだった

It was me who was stupid.- This sentence is about:

- dare ga baka datta?

誰がバカだった?

Who was stupid? - i.e. baka datta is the topic, ore/dare is focus.

- In other words, {omae-ra ni kiita} ore ga baka datta is used only when I asked something to "you guys," omae-ra, and then omae-ra said something stupid, but the sentence is saying it wasn't omae-ra who were stupid, it was me who was the stupid one for asking omae-ra.

Bakayaro!

The phrase baka yarou 馬鹿野郎 means literally "stupid guy," a way to call someone stupid, but it tends to be translated with expletives: you dumbass, you moron, etc..

This happens because yarou 野郎 is refers to men, guys, and it's often used rudely, making it get translated to "bastard" a lot.

Due to yarou やろう ending in a long vowel, it's also romanized as yarō, yaro, and may be also spelled yaroo ヤロー.

- Context: a character feels left out of the group.

- baka yaroo!!

バカヤロー!!

[You] dumbass!! - mochiron omae mo

nakama da yo!!

もちろん お前も 仲間だよ!!

Of course you're nakama too!!

Bakamono!

The word bakamono 馬鹿者 means the same thing as baka yarou, except in anime yarou is used more by urban, gang, or delinquent characters, while mono is used by classier, richer, and often older characters. Also, mono 者 only means "person," so it's gender neutral.

- Context: don't you know who I am?!?!?!

- chuui-dono

nandesu

kono gaki...

中尉殿 なんです このガキ…

Lieutenant, [what is it with] this kid? - *punches*

- de' でっ

- Likely from:

- itee 痛ぇ

- itai 痛い

[It] hurts.

- baka mono!!

馬鹿者!!

[You] idiot!!

Bakame!

The phrase baka-me バカめ means the same thing as baka, but it has condescending the me め suffix. This suffix is humble when used toward oneself, but derogatory when used toward others.

- watakushi-me

私め

I. (humble speech, because I'm referring to myself as inferior with ~me.)- Note: watakushi ワタクシ is a formal variant of watashi ワタシ, both mean "I," "me."

- See: first person pronouns.

- baka-me!

バカめ!

[You] idiot! (derogatory speech, because I'm referring to others as inferior with ~me.)

Kono Baka!

The phrase kono baka このバカ means literally "this idiot," given that the demonstrative pronouns kono この, sono その, and ano あの means "this" and "that." However, in Japanese, "this X" is often used to say something about "you", rather than a third person.

- kono baka!

この馬鹿!

This idiot! (the idiot I'm dealing with.)

You idiot! (yep, this idiot.) - ano baka!

あの馬鹿!

That idiot! (a different idiot.)

This phrase can be combined with the others we saw previously:

- kono baka yarou!

この馬鹿野朗!

This stupid bastard! - kono baka me!

この馬鹿目!

This idiot!

See Swearing with Kono この for details.

Baka na

The phrase baka na バカな is the attributive form of baka da バカだ. The attributive form is necessary when a predicate is part of a relative clause qualifying a noun, which, in Japanese, occurs most of the time a predicate comes right before a noun. Observe:

- kono hito wa baka da

この人はバカだ

This person is an idiot.

This person is stupid.

- {baka na} hito

バカな人

A person [that] {is an idiot}.

A person [that] {is stupid}.

A stupid person.

An idiotic person. An idiot.

- baka na バカな, attributive adjective, relative clause.

- hito 人, noun.

As you can see above, any time you have "subject wa baka da," you can relativize the subject to "{baka na} subject." For simple adjectives, the English relative clauses "X [that] {is stupid}" is too verbose, so we just put the adjective before the noun instead: "stupid X."

- kono inu wa baka da

この犬はバカだ

This dog is stupid. - {baka na} inu

バカな犬

A dog [that] {is stupid}.

A stupid dog. - koitsu wa baka da

こいつはバカだ

This guy is stupid.- koitsu こいつ comes from koyatsu こやつ, the demonstrative ko~ prefix plus yatsu やつ, which means an individual "thing" or "person."

- {baka na} yatsu

バカなやつ

A guy [that] {is stupid}.

A stupid guy. - ningen-domo wa baka da

人間共は馬鹿だ

Humans are stupid. - {baka na} ningen-domo

馬鹿な人間ども

Humans [that] {are stupid}.

Stupid humans. Foolish humans.

Note that there's no distinction between restrictive (ONLY the ones THAT are stupid) and nonrestrictive (WHICH are ALL stupid) relative clauses in Japanese, just as there's no way to distinguish plurality and definiteness in nouns.

- {baka na} otoko

バカな男

A man [who] {is stupid}. (a random, single man.)

The men [that] {are stupid}. (as opposed to the smart men.)

Men, [who] {are stupid}. (all men.)

In many cases, the na な is omitted, and the phrase becomes a single noun. In particular, this happens with nicknames.

- {baka na} yarou

バカな野郎

A guy [that] {is stupid}. - baka-yarou

ばか野郎 - {baka na} oniichan

バカなお兄ちゃん

[My] older brother [who] {is stupid}.

[My] stupid older brother. - baka-oniichan

バカなお兄ちゃん - baka-imouto

バカ妹

Stupid younger sister. - baka-gaijin

バカ外人

Stupid foreigner. - Bakaguya

ばかぐや

The nickname for the "stupid," baka, Kaguya かぐや, from Kaguya-sama wa Kokurasetai かぐや様は告らせたい.

Japanese permits first person pronouns to be relativized more easily than English.

- watashi wa baka da

私はバカだ

I'm stupid. - {baka na} watashi

バカな私

Me, [who] {is stupid}.

The stupid me.

What's stupid doesn't need to be a person or animal.

- {baka na} koto

馬鹿なこと

A thing [that] {is stupid.}

A stupid thing. - {baka na} yume

馬鹿な夢

A dream [that] {is stupid}.

A stupid dream - {baka na} mane wa yose

バカな真似はよせ

Stop doing something [that] {is stupid}.

- Used when someone is doing something stupid, and you tell them to stop.

As an adjective, baka can be preceded by the pronouns konna, sonna, anna, and donna.

- sonna baka na koto wa arienai!

そんな馬鹿なことはありえない!

Something that stupid can't be!

The phrase above is where the infamous BAKANA!!! comes from.

- nanii!! sonna baka na!!

なにィ!!そんなバカな!!

Whaat!! [Something] that stupid [can't be]!!

The attributive form of the predicative janai is also janai. This means that, while you need to replace the affirmative da だ by na な, you don't need to change the negative janai. Observe:

- kono hito wa baka janai

この人バカじゃない

This person isn't stupid. - {baka janai} hito

バカじゃない人

A person [that] {isn't stupid}.

People [that] {aren't stupid}.

Are You Stupid?

There are various ways to ask whether someone is stupid in Japanese, each with a different nuance.

- baka ka?

バカか?

[Are] [you] stupid? - baka desu ka?

バカですか? - baka na no?

バカなの? - baka na no ka?

バカなのか? - baka na no desu ka?

バカなのですか? - baka ka yo?

バカかよ? - baka na no ka yo?

バカなのかよ?

Let's go through them one by one.

Baka ka?

The ka か particle is generally used when there's doubt. As a sentence-ending particle, it's used to make questions. These don't need to be sincere questions seeking new knowledge. Sometimes they're spouted out of surprise or shock at something absurd.

Syntactically, ka か can't come after da だ, but it can come after desu です.

- baka da

バカだ

(becomes...) - baka ka?

バカか?

Are [you] stupid? - baka desu

バカです

(becomes...) - baka desu ka?

バカですか?

Are [you] stupid? (polite form.)

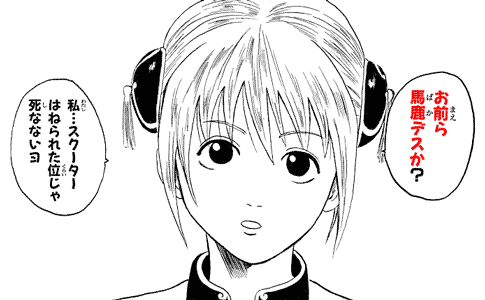

- Context: Kagura 神楽 gets hit by a scooter.

- omaera baka desu ka?

お前ら馬鹿デスか?

Are you [guys] stupid? - watashi... {sukuutaa hanerareta} gurai ja shinanai yo

私・・・スクーターはねられた位じゃ死なないヨ

I wouldn't die just from {getting hit by a scooter}.- desu and yo are unusually spelled with katakana in Kagura's speech to represent her foreign accent.

- See: aesthetic spelling choices.

In English, questions feature subject-auxiliary inversion, in which auxiliaries and the copula "to be" swap places with the subject.

- You are stupid.

- Are you stupid?

Japanese doesn't have this feature. The standard complement order is identical for both interrogative and affirmative sentences.

- omae wa baka da

お前はバカだ

You are stupid.

You are an idiot. - omae wa baka ka?

お前はバカか?

Are you stupid?

Are you an idiot?

In practice, however, it's common to see the question above with the subject ending up in front of the predicate.

- baka ka omae?

バカかお前?

*Are stupid, you? (literally.)

Stupid, are you? (closest grammatical sentence in English.)

This is called a dislocation. More specifically, it's a type of dislocation without a pause called emotive right-dislocation(Ono, 2006, as cited in Nakagawa, 2008:15).

This is what happens in sentences like:

- kore wa nanda?

これはなんだ?

What is this? - nanda kore wa!

なんだこれは! - kore wa nani?

これはなに?

What is this? - kore nani?

これなに? - nani kore?

なにこれ

An example of non-paused dislocation would be:

- kimi wa baka da na

君はバカだな

You are stupid, [aren't you?]- The sentence-ending na な particle is used to ponder things.

- baka da na, kimi wa

バカだな、君は

Baka ka yo?!

The phrase baka ka yo バカかよ means "are you stupid?!" or "are they stupid?!" used as a retort when in shock or disbelief.

The yo よ particle is used in affirmative sentences to correct a wrong assumption of someone else, or to alert someone else about something.

- kore da yo

これだよ

[It] is this. (not that, this.) - muri da yo

無理だよ

[It] is impossible. (give up trying.) - nigeru-n-da yo!

逃げるんだよ!

Run away!

In the interrogative, it's typically used as a retort when something appears or sounds ridiculous.

- muri ka yo?!

無理かよ?

[It] is impossible?! (come on!) - omae ka yo?!

お前かよ?!

[It] is you?! (it was you who was doing it?!) - Context: someone runs over 30km per hour.

- kuruma ka yo?!

車かよ?!

Is [he] a car?! - baka ka yo?!

バカかよ?!

Is [this guy] an idiot?!

By the way, da yo ne だよね and da yo na だよな are used when stating one's opinions and seeking agreement from the listener. Only the ne ね particle requires a listener, the na な particle can be used toward oneself in monologues.

- baka da yo ne

バカだよね

[He] is an idiot, [don't you agree]?

He's such an idiot, right? - baka da yo na

バカだよな

[He] is an idiot, [huh].

[After all], [he] is an idiot.

Baka nano?

The phrase baka nano? バカなの? means "are [you] stupid?" but it's used more by women than by men.

- baka na no?

バカなの?

[Are you] stupid?

How this sentence works exactly is a bit difficult to explain.

In Japanese, some language constructions tend to be used more by one gender than the other. The language used by women is called female language.

For example, the wa わ sentence ending particle is used mostly by women. If you may have seen an ojousama お嬢様 character ending her sentences with desu wa ですわ, that wa わ is the sentence ending particle.

Regarding na no なの, it's an abbreviation of na no ka なのか, which is the interrogative variant of na no da なのだ.

The no の of na no da なのだ is often abbreviated to n ん, making it become na-n-da なんだ.

When a predicate comes before a noun to quality it, it must be converted to "attributive form," rentaikei. The da だ copula is in "predicative form," shuushikei, while the na な copula is in "attributive form," rentaikei.

The no の of na no da なのだ is syntactically treated like a noun, so when baka da バカだ comes before it, it becomes baka na バカな.

The no da のだ, n-da んだ construction has multiple functions. The one we're dealing with has to do with the modality (a.k.a. the mood) of the sentence.

One of them is to make an observation that explains why something is the way it is, and another one is to explain to someone why something is the way it is. For example:

- baka da

バカだ

[He] is an idiot. - baka na no da

バカなのだ

[It's because] [he] is an idiot. (explaining to someone else.)

[Oh, it's because] [he] is an idiot. (realizing it yourself.) - baka na-n-da

バカなんだ - baka na no desu

バカなのです - baka na-n-desu

バカなんです

In the affirmative, the predicate (baka da) serves as the explanation. In the interrogative, the question asked is whether the predicate is the explanation.

- baka na no ka?

バカなのか?

[Is it because] [he] is an idiot? (him being an idiot would explain all of this.) - baka na no?

バカなの? - baka na no desu ka?

バカなのですか? - baka na-n-desu ka?

バカなんですか?

Although this sounds a bit complicated, the idea is that the interrogative can be answered by the affirmative.

- ano ko wa baka na-n-desu ka?

あの子はバカなんですか?

Is that kid stupid? (given that they did something stupid?) - baka na-n-desu

バカなんです

[They] are stupid. (that's why they did something stupid.)

[Yes].

In practice, baka na no ka and its variants end up being used more than baka ka, since most of the time you'll see someone doing something stupid and question whether they do stupid stuff BECAUSE they are stupid, i.e. if the explanation for their stupid actions is that they're stupid themselves.

If na no ka takes in consideration the situation, context, then just ka does not. It tends to be used when ignoring the situation and directing the question wholly to the person, so a complex answer can't be given, and as such the sentence becomes a yes or no question.

- baka ka dou ka

バカかどうか

Whether or not [he] is an idiot.

Baka Janai no?

The phrase baka janai no? バカじゃないの? means, literally, "are [you] not stupid?" but in practice it's just another way to say "are you stupid?"

The no の at the end of the sentence is the same as na no なの, which means janai no is an abbreviation of janai no ka じゃないのか that tends to be used more by women.

Since no の is a noun, da だ is conjugated to its attributive form na な. The same does apply to janai じゃない, but its predicative and attributive forms are identical—the attributive of janai is also janai—so the word doesn't change when it goes before no の to form janai no じゃないの.

Ironically, although baka janai no is syntactically the negative of baka na no, both sentences are equally used to ask whether someone "is" stupid. The difference is that janai poses the doubt as a negative question.

This is easier to understand in English:

- You are stupid, aren't you?

- He is stupid, isn't he?

In the sentences above, the question isn't "are you stupid?," it's "are NOT you stupid?" The same phenomenon happens in the Japanese language, except that the negative question tends to be use rhetorically.

- baka na no ka?

バカなのか?

Is [he] stupid? (affirmative question.)- Used when the speaker isn't sure if he is stupid or not, and is genuinely asking.

- baka janai no ka?

バカじゃないのか?

[He] is stupid, [isn't he]? (negative question.)- Used when the speaker has already assumed that he is stupid and is seeking confirmation.

For comparison:

- kore na no ka?

これなのか?

Is [it] this? (genuine question.) - kore janai no ka?

これじゃないのか?

Isn't [it] this? (I thought it was.)

Since baka janai no? comes with the assumption someone is stupid, it's harsher than simply asking baka na no? and tends to be used to call people morons.

- baaaaakka janee no!?

ば~~~~っかじゃねぇの!?

Aren't [you] stuuuuuupid?- nee ねぇ - contraction of nai ない.

Baka no

The phrase baka no バカの means "an idiot's."

In this case, the no の particle marks the genitive case, which is when a noun modifies another noun. Since baka isn't a noun, being marked by no の turns it into a noun, so it refers to "an idiot," rather than being "stupid."

This process also turns the noun into an adjective, specifically called a no-adjective. There are various kinds. The one we're talking about are possessive, which means the modified noun is a possession of the no-adjective. Observe:

- baka no iken wa doudemo ii

馬鹿の意見はどうでもいい

The idiot's opinion doesn't matter.

[I don't care for] the opinion of an idiot.

No Baka

The phrase no baka のバカ means "[someone]'s stupidity," i.e. "[someone]'s fault."

This is the same thing as baka no but in reverse. Since no の requires both the word before and after to be nouns, in this case, too, baka バカ becomes a noun rather than an adjective.

So we're talking about the "stupid" of somebody, which, in practice, means whose fault was it. However, it's typically translated to English as simply calling someone stupid. For example:

- watashi no baka!

私のバカ!

[It's] my stupid. (literally.)

I'm at fault.

I was the stupid one.

I'm stupid. (typical translation.) - anata no baka!

あなたのバカ!

[It's] your stupid. (literally.)

You are at fault.

You're stupid. (typical translation.) - oniichan no baka!

お兄ちゃんのバカ!

[It's] [my] older brother's stupid! (literally.)

Older brother, it's your fault!

Stupid older brother! (typical translation.)

Baka ni Suru

The phrase baka ni suru バカにする means "to treat [someone] like an idiot," in other words, "to mock [someone]."

- {ore wo baka ni suru} tsumori ka?

俺をバカにするつもりか?

Is [it] [your] intention {to treat me like an idiot}?

Are you trying to make me look like an idiot? - baka ni sareta...

バカにされた…

[Someone] treated me like an idiot...

[Someone] made fun of me...- sareta された is the past form of sareru される, which is the passive form of suru する.

- See passive voice.

Although this sounds very simple, the reason why baka ni suru means what it means is a bit complicated.

The ni suru にする part is the lexical causative counterpart of ni naru になる. Together, these two verbs form an ergative verb pair of eventivizers.

The article about eventivizers contain all the complicate grammar about naru and suru.

The ni に is an adverbial copula, also known as the ren'youkei of da だ. For i-adjectives, ~ku ~く is the ren'youkei, so ~ku naru ~くなる, ~ku suru ~くする, would be used instead.

The naru なる eventivizer means a state will become true in the future, while the suru する eventivizer means someone will make it become true in the future. For example:

- sekai ga heiwa da

世界が平和だ

The world is peaceful. - sekai ga heiwa ni naru

世界が平和になる

The world will become peaceful.

The world will be peaceful. - ore ga sekai wo heiwa ni suru

俺が世界を平和にする

I will make the world be peaceful.

The same thing should work if we replace heiwa 平和 with baka バカ.

- Hanako ga baka ni naru

花子がバカになる

Hanako will become stupid. - Tarou ga Hanako wo baka ni suru

太郎が花子をバカにする

Tarou will make Hanako become stupid.

If Tarou somehow had the power to make Hanako actually stupid—like if he had a potion that decreased someone's intelligence, and he was going to make Hanako drink it, or something like that—then the sentence would be valid.

However, what we want is "treat," not "make," so the sentence makes no sense. Treating someone like an idiot doesn't actually make them an idiot, right?

Well, in Japanese, naru and suru can also mean "to end up serving as X" and "to treat X as Y," respectively. For example:

- Context: the princess is dead. The demon cleric tells the demon lord how she died.

- chiiin

ちーーーん

*ring of a bell* (sound effect used when a character dies or is defeated, probably originates from the bell used in a butsudan 仏壇, a "Buddhist altar" for a deceased family member.) - doku kinoko no boushi wo futon ni shita sou desu...

毒キノコの帽子を布団にしたそうです・・・

It seems that [she] made a poisonous mushroom's cap into a bed.- In other words, she used the cap (top part) of the mushroom as if it were a bed.

- She treated it as a bed.

- futon

布団

Traditional Japanese bedding, typically placed on a tatami floor. The term refers to both the mattress and the duvet, but just "bed" is a good enough translation most of the time..

- moshikashite baka na no ka?

もしかしてバカなのか?

Could it be that [she] is an idiot?

In similar way, baka ni suru normally means to treat someone like an idiot, rather than literally turning them into an idiot.

Baka ni Suru Na!

The phrase baka ni suru na! バカにするな! means "don't treat me like an idiot!" This is simply the phrase baka ni suru with the negative imperative na な particle at the end of the sentence.

- rouka wo hashiru na!

廊下を走るな!

Don't run on the corridor! - baka wo iu na!

バカを言うな!

Don't say stupid! (literally.)

Don't say stupid things!

Don't say absurd things! - ore wo baka ni suru na!

俺をバカにするな!

Don't treat me like an idiot!

Baka ni Shinaide!

The phrase baka ni shinaide! バカにしないで! means "don't treat me like an idiot," too, except in this case it's the naide ないで form being used, so it's closer to a request than an order: someone is asking someone else not to treat them like an idiot.

- Context: Kaguya is asked a quiz question that's too easy for a genius like her, and congratulated after getting it right.

- baka ni shinaide kudasai...

馬鹿にしないでください・・・・・・

Please don't treat [me] like an idiot.

Please don't take [me] for stupid. - konna kodomo-muke no mondai

tokete touzen desu...

こんな子供向けの問題

解けて当然です・・・

A question [made] for kids like this,

solving [it] is [only] natural...

Baka Suffix

Sometimes, baka comes after another word, as a suffix. In this case, it indicates someone is "stupid" for something, the kind of stupid that's fixated on something, like they love something too much or love doing something too much. For example:

- sentou baka

戦闘バカ

Fighting-stupid. (someone who is this loves fights, battles, etc.) - karuta baka

歌留多バカ

Karuta-stupid. (someone who loves the game of karuta)

(example: protagonist of Chihayafuru, manga and anime about karuta) - oya-baka

親バカ

Parent-stupid. (someone who loves being a parent, has gone stupid about being a parent)

(this is the kind of person that keeps bragging about their child at a stupid frequency)

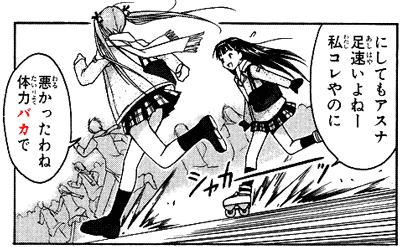

- Context: a tsundere and her friend run to school.

- ni shitemo Asuna

にしてもアスナ

[That said,] Asuna, - ashi hayai yo nee

足速いよねー- [Your] legs are fast. (literally.)

- You [run] fast.

- watashi kore ya no ni

私コレやのに

Even though [for] me, [I] have this.- This means the roller-skates. She's running at the same speed the other is rollerskating.

- warukatta wa ne

悪かったわね

[Well, I'm sorry]- This is sarcasm.

- tairyoku baka de

体力バカで

For being a physical-strength baka.- i.e. for having so much stamina, endurance, agility, strength, etc.

This usage is sometimes used towards people. If you say you're someone-baka, that means you're stupid for someone. That is, you love them. There's nothing in your head except thoughts for them.

bakabakashii

The word bakabakashii 馬鹿馬鹿しい means that something is "stupid," or "foolish." It's not used toward people, only toward things people say.

This word is literally composed of baka twice—this is called a reduplication—plus a ~shii suffix.

It's also spelled bakabakashii バカバカしい. The spelling bakabakakshii 馬鹿々々しい also exists, but using kurikaeshi 々 that way is no longer orthographically valid.

- Context: the student council president thinks a quiz question doesn't make sense.

- bakabakashii...

馬鹿馬鹿しい・・・

[What a waste of time.] (This is stupid.) - konna mono mondai ni natte-inai!!

こんなもの問題になっていない!!

Something like this isn't become a question!! (literally.)- i.e. it's such a bad quiz question it doesn't meet the minimum requirements for the character to acknowledge it's actually a question.

- He thinks quiz questions shouldn't be like this.

References

- Nakagawa, N., Asao, Y. and Nagaya, N., 2008. Information structure and intonation of right-dislocation sentences in Japanese.

- 鈴木彩香, 2014. ガ格の総記/中立叙述用法と裸名詞句の総称/存在解釈の統一的説明. 言語学論叢 オンライン版, (7).

- 馬鹿 - デジタル大辞泉 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2020-11-02.

- 馬鹿・莫迦・破家 - 精選版 日本国語大辞典 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2020-11-02.

- 馬鹿 - gogen-allguide.com, accessed 2020-11-02.

Those articles are great sensei! Thanks for sharing your knowledge!

ReplyDeleteJust wonderful! I watch a TON of anime. Its actually the only thing I watch hahaha I was in the process of calling my friend an idiot and really couldnt remember how exactly to spell baka and if there was anything else I could add to it. Make her Google it just to see shes being a major baka haha thamks so much for all thos information! Really helped me out alot!.

ReplyDeleteWonderful lesson !

ReplyDelete