In Japanese, furigana 振り仮名 is a text written next to a certain character, word, or phrase, that shows how you're supposed to read it. It's also called "ruby text," rubi ルビ (the opposite being base text), or "reading aid," although it also has some non-reading-aid, creative uses.

For example: 今日日(きょうび) shows the word kyoubi 今日日, "these days," "in modern times," which has kanji 漢字 characters. Inside parentheses is the furigana: k-yo-u-bi きょうび, showing how the word is read using hiragana ひらがな characters.

Rendering

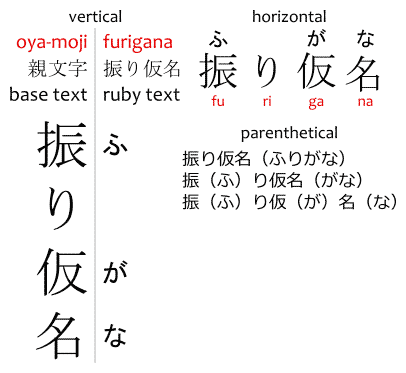

The furigana is rendered in multiple ways.

Secondary Line

In "vertical writing," tategaki 縦書き, the furigana is placed on the right side of the text. In "horizontal writing," yokogaki 横書き, the furigana placed above the text. Although exceptions may exist.

See also: Writing Direction.

In either case, it's typically rendered as a smaller font, due to it typically taking multiple furigana characters to show how a single character in the main text is supposed to be read, although there are exceptions.

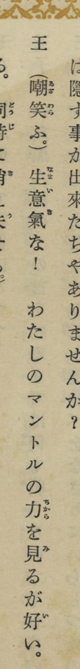

Author: Akutagawa Ryūnosuke 芥川龍之介

Published: Year 3 of the Shouwa 昭和 era, a.k.a. 1922. (see years and eras.)

Source of the image: 三つの宝 - 国立国会図書館デジタルコレクション - dl.ndl.go.jp, accessed 2019-03-22.

The book in plain text, slightly different: 三つの宝 芥川龍之介 - www.aozora.gr.jp, 2019-03-22.

- ou (aza-warafu.) namaiki na! watashi no mantoru no chikara wo miru ga ii.

王 (嘲笑ふ。)生意気な! わたしのマントルの力を見るが好い。

King: (sneers.) naive, [aren't you]! [You shall] see the power of my mantle!

- warafu - old spelling of warau 笑う, "to smile," "to laugh," in parentheses here because it's an action, not a line of dialogue.

Right: Shinya Yukimura 雪村心夜

Anime: Rikei ga Koi ni Ochita no de Shoumei shitemita. 理系が恋に落ちたので証明してみた。 (Episode 1, Stitch)

- Context: a couple studies the perfect angle for a certain romantic move.

- agokui.

顎クイ。

Holding up someone's chin (for a kiss).- Here, 顎 has あご as furigana.

In Parentheses or Brackets

When it's not possible to put the furigana in a second line, maybe due to layout limitations, it's written in parentheses, or in brackets, after the word. Dictionaries, in particular, tend to use brackets.

- 漢字(かんじ)

- 漢字【かんじ】

Some words feature a mix of kanji and kana characters, such as the okurigana 送り仮名. The furigana may be written after each kanji, or kanji sequence, or after the whole word and include the kana.

- 振(ふ)り仮(が)名(な)

- 振(ふ)り仮名(がな)

- 振り仮名(ふりがな)

This parenthetical layout is common on the internet due to lack of browser and editor support for adding ruby text annotations to characters.

In HTML

It's possible to add furigana in HTML through the <ruby>, <rp>, and <rt> elements. The <ruby> surrounds the whole annotated text, the <rp> is a child element containing parentheses for backward compatibility, and <rt> is the ruby text.

For example, something like this:

- 振(り)り仮(が)名(な)

Would be rewritten like this unholy mess:

<ruby>振<rp>(</rp><rt>ふ</rt><rp>)</rp></ruby>り<ruby>仮<rp>(</rp><rt>が</rt><rp>)</rp>名<rp>(</rp><rt>な</rt><rp>)</rp></ruby>

In order to look like this:

- 振り仮名

And if it looks like furigana to you, that means your web browser supports it. If your browser doesn't support it, it should look like parentheses with the furigana inside.

Furigana in the Furigana

In rare cases, the furigana has its own furigana, which means the furigana is being used for two different purposes.

This can happen, for example, if a text is in old Japanese, which was pronounced differently, so the kanji has its reading written over it, and the reading may have its modern pronunciation written over it.

| Modern pronunciation (mi-zu) | ず | |

|---|---|---|

| Original reading (mi-dzu) | み | づ |

| Kanji | 水 | |

This sort of furigana stacking is even less supported in web browsers.

- 水

Purpose

The furigana can be used in various ways. The text in the furigana may contain:

- A reading aid in hiragana ひらがな, showing how to read the kanji 漢字.

- ka 蚊

か , "mosquito." - kumo 蜘蛛

くも , "spider." - kyou 今日

きょう , "today." - manji 卍

まんじ ., "swastika." - tamashii 魂

たましい , "soul." - kokorozashi 志

こころざし , "ambition." - kuri-kaesu 繰

く り返かえ す, "to repeat."

- ka 蚊

- A reading aid for a symbol or number.

- A reading aid showing how to pronounce old Japanese (kobun 古文), or obsolete characters.

- karakurenai からくれなゐ

い , "crimson." - mizu みづ

ず , "water."

- karakurenai からくれなゐ

- The katakanization of a phrase in foreign script in katakana カタカナ.

- sankyuu THANK YOU

サンキュー , an English phrase.[example] - maajan 麻雀

マージャン , "mahjong," a Chinese term. - omega Ω

オメガ , a Greek letter.

- sankyuu THANK YOU

- Dots, circles, or similar marks, which are used for emphasis, called bouten 傍点. These aren't actually part of the furigana, they're merely written in the same space as the furigana would.

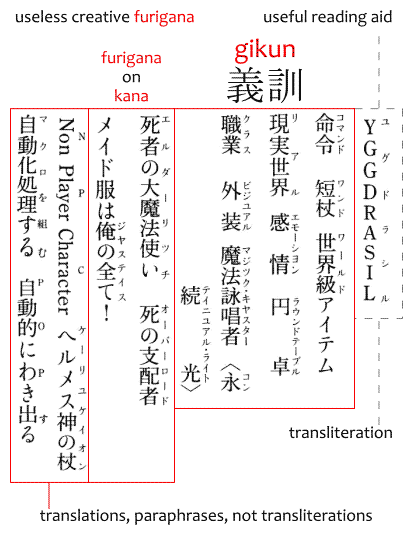

- Literally anything else, called a gikun 義訓, "artificial reading." Common cases include:

- An ateji 当て字: using a word in furigana, then selecting kanji for that word, typically that match the word's meaning, specially with loan words that don't have kanji, and made-up terms in fictional stories for cool weapons, abilities, etc., in manga and light novels.

- tabako 煙草

タバコ , "(tobacco) smoke-grass." - (ekusukaribaa) seiken 聖剣

エクスカリバー , "(Excalibur) holy-sword." - (ootomeiru) kikai-yoroi 機械鎧

オートメイル , "(automail) machine-armor."[used in Fullmetal Alchemist] - (kuuhaku) 「 」

空白 , "(blank)," never loses.(used in No Game No Life, ノーゲーム・ノーライフ)

- tabako 煙草

- The Japanese translation of a phrase in another language.

- (subarashii) tore bian トレビアン

素晴らしい , "(marvelous) très bien."[example] - Non-Player Character

NPC , because Japanese speakers may know what the gaming term "NPC" means, but not know the English phrase "non-player character" that NPC abbreviates.[used in Overlord]

- (subarashii) tore bian トレビアン

- The meaning or expansion of an acronym.

- A synonym, likely one that only makes sense in that context, specially deictic pronouns.

- An ateji 当て字: using a word in furigana, then selecting kanji for that word, typically that match the word's meaning, specially with loan words that don't have kanji, and made-up terms in fictional stories for cool weapons, abilities, etc., in manga and light novels.

Reading Aid

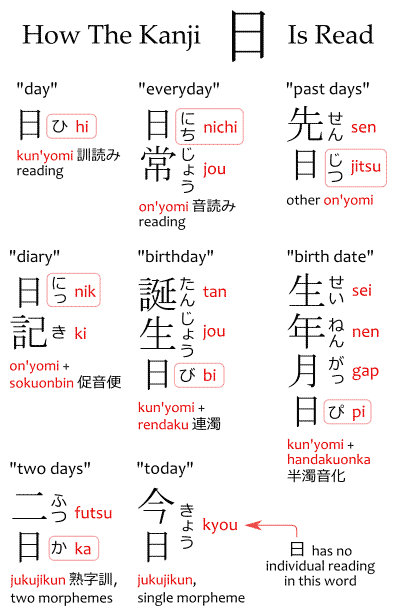

The main purpose of the furigana is to serve as a reading aid, but why are reading aids necessary in Japanese? This has to do with how the Japanese "alphabet" works.

Most Japanese words are spelled with kanji 漢字, "Chinese characters" that were loaned into Japanese long, long ago.

There are around 2000 (two THOUSAND) kanji that a Japanese native speaker is supposed to be able to read by high school. These are called jouyou kanji 常用漢字.

Besides their sheer number, a single kanji character can be read in multiple different ways depending on the word that it's part of. There are several reasons for this. The outcome is that the only way to know you're reading a kanji right is to check a dictionary, or look at the furigana.

See Same Kanji, Different Reading for details.

Besides the kanji, the Japanese language also has characters called the kana 仮名 (the hiragana ひらがな and katakana カタカナ).

Each kana represents a single syllable, e.g. hi-ra-ga-na ひらがな. They're always read the same way, regardless of word.

The furigana refers to using these kana, which are always read the same way, as reading aid for the kanji, which are read in random ways, so that a reader that can't read that kanji, that can't read the word spelled with that kanji, becomes able to read it.

Of course, just because you know to read a word, that doesn't mean you know what the word means.

- You can read semordnilap, an English word, without having any idea about what in the world that's supposed to be.

But at least with furigana you can read the kanji now. Except if you can't read the kana, then you can't read Japanese at all, and the furigana won't help you. In that case, romaji ローマ字 is used to allow readers that can't read Japanese at all to read Japanese words.

- Context: the staff card of an OL character, showing her name with furigana in romaji.

- gurafikkaa

グラフィッカー

"Graphic-er." (wasei-eigo 和製英語.)

Graphic artist. - Suzukaze Aoba

涼風青葉

It's worth noting that not all words are spelled normally with kanji, nor do all words HAVE kanji associated with them at all, and among the words spelled with kanji, some are only partially spelled with kanji, and the other part is hiragana.

Among such cases, the okurigana 送り仮名 refers to the kana written AFTER a kanji that hints how it's supposed to be read, in a manner similar to the furigana. For example:

- hosoi

細い

Thin. - komakai

細かい

Detailed.

The words above have the same kanji, but different okurigana. The 細 kanji is only read as hoso~ if the okurigana is ~i, and only read as koma~ if the okurigana is ~kai.

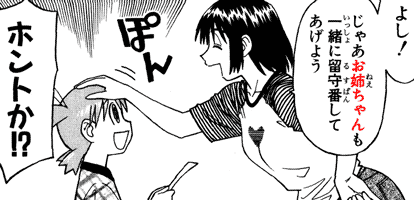

Content for Young Audiences

Since you're expected to know the commonly used kanji by high school, that conversely means you can't be expected to know them BEFORE high school. As such, content that targets younger demographics tend to have furigana, while content that targets older audiences do not.

You only know the readers won't know ALL the kanji, you don't know WHICH kanji they know, and which ones they don't, so it's difficult to figure out which kanji should get furigana, and which one should not.

The solution is to simply put furigana on everything. That's right: furigana on ALL words. Write everything twice.

- Context: upon returning home with Ayase Fuuka 綾瀬風香: Yotsuba finds a note from his father saying that he went to the store and that she should take care of the house while he's away. Learning this, Fuuka says:

- yoshi!

よし!

Alright! - jaa oneechan mo {issho ni} rusuban shite-ageyou

じゃあお姉ちゃんも一緒に留守番してあげよう

Then [I]'ll [stay here] {together [with you]}..- oneechan - "older sister," also a way to refer to young women not related to you, and used by them to refer to themselves, too, specially when talking to children.

- rusuban - "stay-at-home duty," in the sense of someone leaving home, and someone else staying there to take care of the house.

- ~te-ageyou - volitional form of ~te-ageru ~てあげる, [to do something] for [someone else]."

- pon

ぽん

*head pat* - honto ka!?

ホントか!?

Really?- honto - same hontou 本当, with long vowel shortened.

- honto - same hontou 本当, with long vowel shortened.

In Manga

As a general rule, a word in a shounen manga or shoujo manga will have furigana, while in a seinen manga it will not.

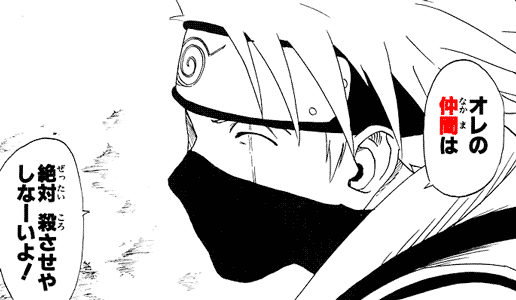

- Context: the most shounen thing in the universe.

- ore no nakama wa zettai korosase ya shinaai yo!

オレの仲間は絶対 殺させやしなーいよ!

[I] absolutely won't let [you] kill my nakama!- korosaseru - "to let kill," causative form of korosu 殺す.

- ya shinai - same as wa shinai はしない.

- korosase wa shinai - same as korosasenai 殺させない, "won't let kill," with a wa は particle marking the act as topic.

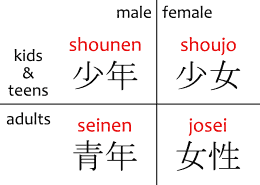

The terms shounen 少年 shoujo, 少女, seinen 青年, and josei 女性 are used to categorize demographics: shounen and shoujo are kids and teens, seinen and josei are adults, and shoujo and josei are female audiences.

If you started learning Japanese to read manga, but can't read many kanji yet, it's recommended to read such manga for children since they have furigana.

You still won't know what the word means, but knowing how it's read helps since you can easily look up the word by typing its reading in whatever Japanese IME you're using, pressing space to convert it to kanji, and looking it up in an online dictionary.

Without knowing the reading, things get more complicated: you can look up the kanji by its components, which takes too much effort if you come across too many kanji you don't know, or you could use a Japanese OCR software that tries to recognize what's written in an image.

If you want to read manga, start with manga with furigana. If you don't have a particular interest in reading manga, web novels and news websites make more sense, since you can easily select the text you don't know to look up what it means, regardless of whether you can read it or not.

There's also the opinion that it's better to avoid content with furigana, since you end up relying on the furigana to be able to read the kanji, and, as such, you won't memorize the reading of the kanji, and you won't make any progress learning the language.

In such case, seinen manga, for older audiences, make more sense, since they generally lack furigana, as they assume their audience knows how to read.

There are some exceptions. The following may lack furigana in manga for young audiences:

- Symbols like ○ and ×.

- In particular, two circle marks, X marks, or triangles in sequence are placeholders, e.g. __-san 〇〇さん, ××さん, △△さん could be "Mr. A, Mr. B, Mr. C" without using a word for their names.

- Numbers spelled with Arabic numerals (1234567890).

- e.g. ni-sen-nen 2000年

ねん , "year 2000."

- e.g. ni-sen-nen 2000年

- Numbers spelled with kanji (一二三四五六七八九).

- e.g. san'nin 三人

にん , "three people."

- e.g. san'nin 三人

- Very common words, or kanji taught in very early grades.

- e.g. nihon 日本, "Japan," is spelled with two kanji taught in the first year of elementary school.

These may vary from publisher to publisher, from time to time. In particular, older shounen manga tend to miss more furigana, suggesting there might have been editorial standards may have changed since then.

- In JoJo no Kimyou na Bouken ジョジョの奇妙な冒険, published in 1986, many words lack furigana, such as te 手, "hand," kusuri 薬, "medicine," or only have partial furigana, such as tobi-deru 飛

と び出る, "to jump out of." However, most of the text does have furigana.

Content for very young children may lack kanji altogether, spelling everything with hiragana.

There are also cases where furigana isn't used, but words normally spelled with kanji taught in later grades are spelled with hiragana.

- In Doraemon ドラえもん, words like kowai 怖い, "scary," and yume 夢, "dream," are spelled with hiragana. Despite its kanji being taught in an earlier grade, koi 来い, "come (imperative)," is also spelled with hiragana, most likely due to it being an irregular conjugation: the meireikei 命令形 of the irregular verb kuru 来る, "to come."

Unusual Kanji Readings

Content that doesn't have furigana on all words may still have furigana for kanji that the average reader may have trouble reading

Although there are around 2000 kanji taught up until high school, those aren't all the kanji in the Japanese language has to offer. There are kanji beyond those that are simply not normally used or deliberately avoided.

Some words have kanji, but because they're normally spelled without kanji, a reader may not recognize them if they were to be spelled with kanji.

- iruka

海豚

Dolphin.- Not read umi-buta 海豚, "sea pig," because it's a jukujikun 熟字訓.

Among these, kanji for names of animals and names of body parts are very likely to be unrecognized.

Many animals have an unique kanji associated with them, but since people don't normally talk about animals, they don't normally read those kanji, so they're more likely to forget what it's supposed to mean. The same applies to body parts.

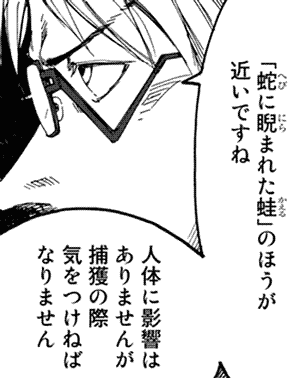

- Context: Tosaki Yuu 戸崎優 talks about the ability to paralyze humans that the ajin 亜人, "demi-humans," have.

- {"{hebi ni niramareta} kaeru" no} hou ga chigai desu ne

「蛇に睨まれた蛙」のほうが違うですね

[It] is closer to {"a frog {glared at by a snake}"}.- {...} hou ga chigai - the {...} way is closer, is more similar.

- niramareta - past form of passive form of niramu 睨む, "to glare at."

- Here, the kanji for the names of the animals "frog" and "snake," as well as the verb "to glare," have furigana, even though the rest of the text lacks furigana.

- {jintai ni eikyou wa arimasen} ga hokaku no sai ki wo tsukeneba narimasen

人体に影響はありませんが捕獲の際気をつけねばなりません

{There's no effect on the human body}, but [we] should be cautious of [it] when capturing [the ajin].- arimasen - polite form of nai 無い, negative form of the irregular verb aru ある.

- ~ba narimasen - should not, must not.

- ~neba narimasen - should not not = should, must.

- ki wo tsuku - to pay attention to, to be cautious of.

- hokaku no sai - in the occasion of capture, when capturing, if we were to try to capture.

Language reforms have changed the way many words are spelled. For example, mawaru 廻る, "to turn (rotating, spinning, in circles)," is now spelled mawaru 回る. A text that uses these old spellings for some reason may have furigana on the kanji.

Names

In Japanese, names of people may be written with kanji, and the kanji that spell names of people can be read in all sorts of unique ways that aren't found in normal words. Consequently, names often get furigana, even if the rest of the text lacks it.

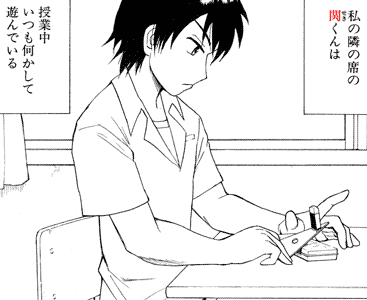

- Context: Yokoi Rumi 横井るみ introduces the series title character.

- watashi no tonari no seki no Seki-kun wa juuygou-chuu itsumo nanika shite asonde-iru

私の隣の席の関くんは従業中いつも何かして遊んでいる

Seki-kun, [who sits next to me], is always playing doing something during class.- watashi no tonari - next of me (neighboring me).

- watashi no tonari no seki - the seat that is next of me, the neighbor seat.

Ambiguous Words

In rare cases, the furigana helps tell apart words that are spelled the same way. For example:

- ichinichi

一日いちにち

One day. - tsuitachi

一日ついたち

First day of the month.

Ambiguous Readings

The kanji for musume 娘, "daughter," is used to spell ko 子, "child," which is also a diminutive way to refer to a random "person," hito 人, when the ko 子 we're referring to is female.

In such cases, it may get furigana to avoid it being misread as ano musume.

- Context: Harima Kenji 播磨拳児 is full of regret.

- chikushou......!!

ちくしょう・・・・・・!!

[Damn it]......!! - {{{suki na} ko to umi ni ikeru} chansu da} tte no ni yo!!

好きな娘こ と海に行けるチャンスだってのによ!!

Even though {[it]'s chance [for] {[me] to be able to go to the beach with the girl [that] {[I] like}}}!!- da tte no ni - contraction of da to iu no ni だというのに.

- umi

海

The sea. (literally.)

The beach. (where you go in English.)

Katakanizations

The furigana may be in katakana if it contains the katakanization of a foreign phrase.

To elaborate: the katakana and hiragana are like lower-case and UPPER-CASE letters: anything you can write with katakana, you can write with hiragana, and vice-versa. In Japanese, the hiragana is used to spell native words, while the katakana is used to spell foreign words.

The way loan-words are pronounced in Japanese is a bit weird, mostly due to there being less sounds in the Japanese language than in English. For example, there's no "L" in Japanese, so words like "laser" become reezaa レーザー, and "leather" becomes rezaa レザー.

The katakanization reezaa レーザー shows how to pronounce the foreign word "laser" for a Japanese audience, just like the romaji "reezaa" shows how to pronounce "レーザー" for a non-Japanese audience.

These katakanizations may be found as furigana when the base text is in a foreign script, e.g. in English.

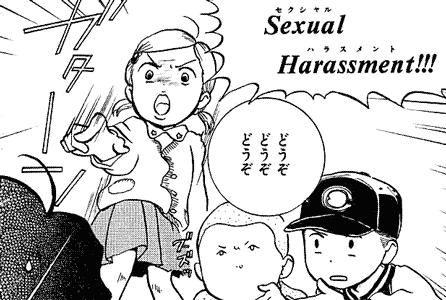

- Context: as per village custom, a village official has to tell an old tale to the village children. He warns the tale contains rather mature scenes. The children react:

- sekushuaru harasumento!!!

SEXUALセクシュアル HARASSMENTハラスメント !!!

[That's] sexual harassment!!! - douzo douzo douzo

どうぞどうぞどうぞ

[Go on, go on, go on].- douzo - suit yourself, go on, do as you please, etc., used when telling someone you don't mind if they proceed with something, in this case, to proceed with the story..

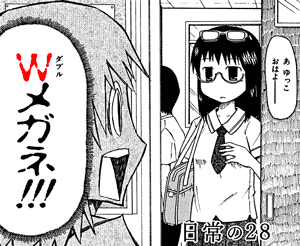

- Context: Minakami Mai 水上麻衣 greets Aioi Yuuko 相生祐子.

- a, Yuuko, ohayoo

あ ゆっこおはよー

Ah, Yuuko, good morning. - daburu-megane!!!

Wダブル メガネ!!!

Double glasses!!!- daburu - the katakanization of the English letter W.

- A W prefix in Japanese means "double."

Made-up Readings

The furigana ALWAYS shows the correct way to read something, and since you always want to read stuff correctly, the furigana always shows how to read the text altogether. Authors have made use of this feature of the Japanese language to make readers read one text in a way that it wouldn't normally be read, giving the kanji entirely made-up readings. These are called gikun 義訓, "artificial readings."

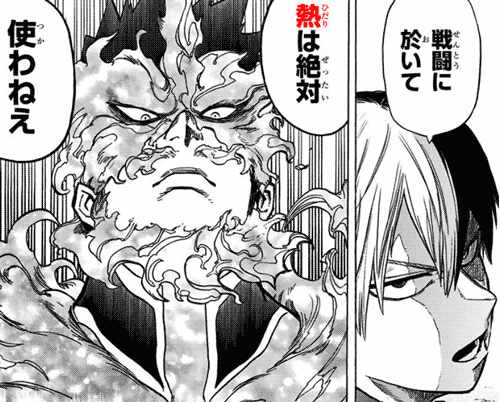

- Context: Todoroki Shouto 轟焦凍 has both cold and heat abilities, which come from the sides of his body: from the right comes cold, from the left comes heat.

- sentou ni oite (hidari) netsu wa zettai tsukawanee

戦闘に於いて熱ひだり は絶対使わねえ

In battle [I] absolutely won't use (left) heat.

Above, the kanji is for the word netsu 熱, "heat," but the furigana says hidari 左, which means "left," and is a completely different word.

The "heat" kanji would never be read hidari in normal situations, nor would the word for "left" be written with the "heat" kanji. It only occurs in this work, specifically, because when this character says he won't use his "left" side, he means he won't use his "heat" ability.

Even then, there isn't any actual necessity to spell "left" with the kanji for "heat," or vice-versa. The author does this anyway because he could, and he could because the Japanese language allows it.

There's no real equivalent in English. I guess the closest thing would be putting the gikun between parentheses before the base text phrase, but I don't think anybody does that when drawing comics.

Needless to say, these fake readings can catch people learning Japanese by surprise. After all, they're reading manga with furigana because they can't read the kanji, so they can't tell apart a kanji's real reading from a fake one.

The fake readings can be anything, while actual reading aids are always hiragana annotating kanji, or katakana annotating non-Japanese text.

In cases like the above, these are ambiguous: when two different words are written, but the word in the furigana is written with hiragana, which makes it looks like it's a reading.

In every other case, it's pretty easy guess the reading is a fake one.

For example, when katakana is in the furigana for a kanji, that's very likely a fake reading. If there's kanji or even alphabet letters in the furigana, that's not even a reading aid anymore.

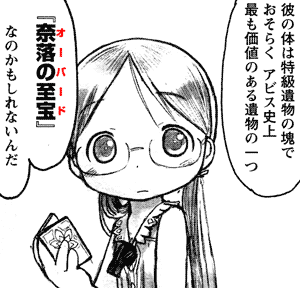

- Context: in a series about searching for relics in a bottomless pit called the Abyss, Riko リコ is told some important information about a robot boy she found in the Abyss.

- {kare no karada wa tokkyuu ibutsu no katamari de}, osoraku, {Abisu shijou mottomo kachi no aru} ibutsu no hitotsu "Naraku no Shihou (Oobaado)" na no kamoshirenai-n-da

彼の体は特級特急遺物の塊でおそらく アビス史上最も価値のある遺物の一つ「奈落の至宝オーバード 」なのかもしれないんだ

{His body is a bunch of special-grade relics, and}, likely, could be one of the relics {of most value in all of the Abyss' history}, an "(Aubade) Precious Treasure of The Abyss."- Here, Oobaado is used as gikun for Naraku no Shihou, because the name for the thing in this series is "Aubade," and what the word means is "Precious Treasure of The Abyss."

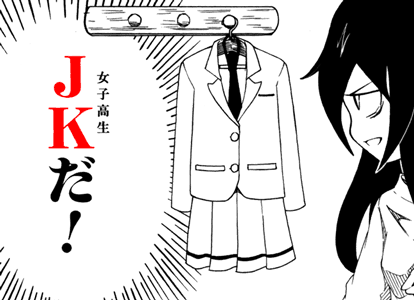

- Context: Tomoko, a middle school girl, talks about what she's about to become.

- (joshi kousei) jeikei da!

JK女子高生 だ!

[I'll] be a (high school girl) JK!- JK, normally pronounced jeikei ジェイケイ, is usually the abbreviation of joshi kousei 女子高生, "high school girl" in Japanese.

Deictic Readings

One case to watch out for are demonstrative pronouns, "this," "that," "here," and other deictic pronouns, "now," "I," "him," "them," specially the kosoado kotoba こそあど言葉, used in the furigana for what they refer to in that context. For example:

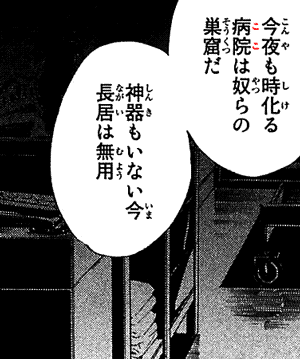

- Context: Yato 夜ト, who is a God fighting spiritual beings related to human's negative feelings, goes to the hospital make a visit to someone, and says:

- kon'ya mo shikeru

今夜も時化る

Tonight, too, will be stormy.- shikeru - for a sea to be stormy. The series is based on Buddhism, using terms like shigan 此岸, literally "this shore," and higan 彼岸, literally "that shore," refer to "this world (of the living)" and "that world (of the dead)," respectively. Consequently, saying "the sea will be stormy" implies those from that world will come to this world in a more chaotic manner.

- (koko) byouin wa yatsura no soukutsu da

病院ここ は奴らの巣窟だ

(This place) the hospital is their lair.- koko ここ, "here," "this place" is used as reading for byouin 病院, "hospital," because "here" is "the hospital," that's where the character was when he said that.

- {shinki mo inai} ima nagai wa muyou

神器もいない今長居は無用

Now [while] {[I] don't have a regalia}, a long-stay is unnecessary.- shinki 神器, literally "divine instrument," also translated to "regalia" in English, refers weapons to fight spiritual beings. Since these weapons are actually other characters that transform into weapons, and not just objects, the animate existence verb iru 居る was used instead of the inanimate aru 在る.

- The temporal noun ima 今, "now," is qualified by a relative clause in this sentence.

- Fantomuhaibu-ke toushu wa

ファントムハイブ家 当主は

The head of the Phantomhive family... - ”Shieru-Fantomuhaibu (kono boku)*” da

”シエル・ファントムハイブ(この僕)”だ

is "Ciel Phantomhive (this me)*."- See kono ore da この俺だ for other examples of "this me" being used in Japanese.

Expanded Abbreviations as Readings

In some cases, the reading of an abbreviation is its expansion. For example:

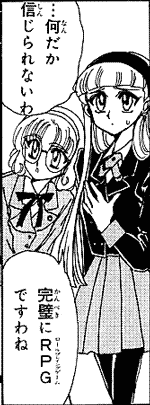

- Context: three girls are told that they were summoned to another world because the princess wished for someone to save the world, so if they save the world the wish will be fulfilled and they'll be able to return to their former world.

- ...nandaka shinjirarenai wa

・・・何だか信じられないわ

... [I] sort of can't believe [it]. - {kanzen ni} (rooru pureingu geemu) aaru-pii-jii desu wa ne

完全にRPGロールプレイングゲーム ですわね

[It] is {completely} a (role-playing game) RPG, isn't it?

In Japanese, RPG is pronounced aaru-pii-jii アール・ピー・ジー, a katakanization of the English letters R, P, and G. Since the expansion "role playing game" was used in the furigana, the character said that phrase.

RPG could have been used in the base text to save space, or because the audience is more familiar with the abbreviation than with the expansion.

Disregard for Morphology

When the furigana contains a completely different phrase, the morphology of the two phrases may get ignored, such that if both phrases end with the same characters, which are often the conjugatable part of the word, those are removed from the furigana and only appear in the base text.

For example, if both phrases end in verbs that end in the ~ru ~る syllable, the syllable only gets written in the base text, and not in the furigana, so if you only look at the furigana, it looks like someone forgot to write the whole word. Observe:

- 外に出

出発す る

Above, we have two phrases:

- shuppatsu suru

出発する

To leave [to go somewhere]. To depart. - soto ni deru

外に出る

To go outside.

Since they both in ~ru, the gikun only reads shuppatsu su~. The auxiliary verb suru する was divided into two.

Some other examples:

- Context: the first chapter of Overlord uses furigana creatively a lot. Overlord is a story about a character who playing a virtual reality MMORPG.

- yugudorashiru

YGGDRASILユグドラシル

- Here, the furigana is a katakanization of the Latin script. While furigana used like this is unusual, it's a reading aid, not a creative use.

- (komando) meirei

命令コマンド

(Command) order.- This and examples below are game terms that are in katakanizations of English words being spelled with kanji that mean basically—and sometimes literally—the same thing in Japanese.

- They're all gikun, since it's the spelling that is used in THIS GAME specifically, and not outside this context.

- In this case, a "command" is an "order" given to an NPC.

- (tanjou) wando

短杖ワンド

("Short stick," wand) wand. - (waarudo) sekai-kyuu aitemu

世界級ワールド アイテム

(World) world-level item.- This term is read "world item," with sekai-kyuu, "world level," being a high item level.

- (riaru) genjitsu sekai

現実世界リアル

(Real) real world.- riaru, a katakanization of "real," is a Japanese slang referring to real life, as opposed virtual life, on a virtual world, like in an online game, or online forum, etc.

- (emooshon) kanjou

感情エモーション

(Emotion) emotion. - (raundo-teeburu) entaku

円卓ラウンドテーブル

(Round table) round table.- As in "knights of the round table," entaku no kishi-dan 円卓の騎士団.

- (kurasu) shokugyou

職業クラス

(Class) job.- In RPGs, the term "class" or "job" refers to a role a character has that defines their abilities, such as the "mage" class having magic abilities, or the "knight" class using a sword, etc.

- (bijuaru) gaisou

外装ビジュアル

(Visual) exterior.- In the sense of how a character looks, with certain appearance settings, cosmetic items equipped, etc.

- (majikku-kyasutaa) mahou eishou-sha

魔法詠唱者マジック・キャスター

(Magic caster) magic chanter.- A mage class in this game.

- (konthinyuaru-raito)

<永続光コンティニュアル・ライト >

(Continual light) persisting light.- The name of a magic spell in this game.

- This word is excerpted as-is: in the page it was found, the line wraps after 永 with コン as furigana.

- (erudaa-ricchi) shisha no dai-mahou-tsukai

死者の大魔法使いエルダーリッチ

(Elder lich) great magic user of the dead.- The name of a class. A lich is an undead sorcerer.

- This example, and the ones below, have a furigana that annotates a whole noun phrase. In particular, shisha no dai-mahou-tsukai contains the no の particle, which is in hiragana, not kanji.

- (oobaaroodo) shi no shihaisha

死の支配者オーバーロード

(Overlord) ruler of death.- shihai suru

支配する

To rule over. To control (a land).

- shihai suru

- meido-fuku wa (jasuthisu) ore no subete!

メイド服は俺の全てジャスティス !

Maid clothes are (justice) my everything!- A character proclaims his love for maids, and maid uniforms.

- Likely from the sense of "cute is justice," and "you are my everything," except maid is justice, and maids are my everything.

- (enu-pii-shii) non pureyaa kyarakutaa

Non Player CharacterNPC

In a game, a character a player controls is a player character, while a NPC is any character that no player controls, like shop-keepers, quest-givers, monsters, and so on.- This isn't a reading aid. A reading aid would be non pureyaa kyarakutaa ノンプレイヤーキャラクター, the katakanization of "Non Player Character." This isn't even a transliteration, as NPC is in the same Latin script as Non Player Character.

- The reason why NPC is used here is because while readers may be familiar with NPC abbreviation found in games, they may not be familiar with the extension "Non Player Character" that comes from English, so NPC works as a Japanese translation for Non Player Character.

- (keeryukeion) Herumesu-shin no tsue

ヘルメス神の杖ケーリュケイオン

(Caduceus) staff of Hermes.- In Greek mythology, the caduceus is a staff carried by Hermes, so the base text contains the true meaning of the katakanized gikun.

- Note that both Hermes and caduceus are in katakana, so this furigana usage can't even be mistaken for a transliteration.

- (makuro wo kumu) jidou-ka shori suru

自動化処理するマクロを組む

(To program a macro) to take care of [it] automatically.- In programming, a macro is a single command that instructs a computer to execute a sequence of commands.

- In this example, the base text explains what the gikun means: programming a macro means making a computer (an NPC in this case) execute a sequence of commands without you having to tell it each and every command every time. In particular, this could be a macro executed in response to something else.

- (poppu su~) jidou-teki ni waki-de~ru

自動的にわき出POPす る

(To pop) to spawn automatically.- In gaming, the Japanese slang poppu suru POPする means for an enemy (or other character) to appear (spawn) in an area. The base text is explaining what this slang means.

Dots in the Furigana

Main article: Emphasis Dots.

Sometimes, dots are written on the furigana space to express emphasis. Ticks or other marks may also be used. These are called bouten 傍点, "side dots."

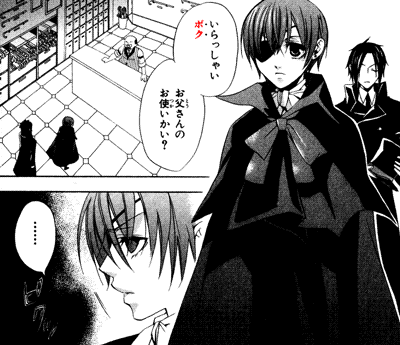

- Context: Ciel Phantomhive シエル・ファントムハイヴ lost his parents and became head of the Phantomhive family. He doesn't like being treated like a child. He enters a store and is greeted by the clerk.

- irasshai boku, otousan no otsukai kai?

いらっしゃいボク お父さんのお使いかい?

Welcome, boy, is [it] [your] father's errand? (literally.)

Are you here doing an errand for your father?- boku 僕 - "boy" (used toward children), also a a masculine first person pronoun.

- piku'

ピクッ

*twitch* (with irritation, in this case.)

If the word emphasized already has furigana, dots may be placed further to the right (or top), or the furigana may be removed to make space for the dots, or, when emphasizing a long phrase, the characters with furigana are skipped, and those without furigana get dots.

- Context: in a series about people that have powers called quirks, a doctor examines Midoriya Izuku 緑谷出久, talks about how quirkless people have two joints in his pinky toe, and then says:

- Izuku-kun niwa kansetsu ga futatsu aru

出久くんには関節が2つある

Izuku-kun has two joints. - {kono sedai ja mezurashii...} {nan'no "kosei" mo yadottenai} kata da yo

この世代じゃ珍しい・・・何の“個性”も宿ってない型だよ

A type {rare in this age}, [that] {doesn't [contain] any quirk}.- yadoru

宿る

To dwell. (in this case, for a quirk to dwell in his body, i.e. for a quirk to be contained in him, for him to contain a quirk.)

- yadoru

If the furigana is in katakana, the dot may also be a middle dot separating words instead.

Line in the Furigana

A line in the furigana space is used for emphasis, too. More specifically, when text is written horizontally, it's underlined, but when it's written vertically, a "side line," bousen 傍線, is added instead.

Meaning of the Word

The term furigana means the kana that you furu 振る. The word furu means "to distribute," and the word kana becomes ~gana as a suffix due to rendaku 連濁.

- buka ni shigoto wo furu

部下に仕事を振る

To distribute work to [one's] subordinates.- There are N tasks and M subordinates, so you furu the tasks to them subordinates.

- kanji ni yomigana wo furu

漢字に読み仮名を振る

To distribute yomigana to kanji.- yomigana

読み仮名

Reading kana. The kana that shows how to read a kanji.

- yomigana

Mainly, furigana refers to adding the reading aids manually. The term rubi ルビ, from "ruby" text, is used in printing.

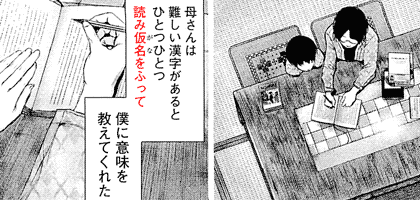

- Context: Kaneki Ken 金木研 talks about his mother.

- kaasan wa {muzukashii kanji ga aru} to {hitotsu-hitotsu yomigana wo futte} boku ni imi wo oshiete-kureta

母さんは難しい漢字があるとひとつひとつ読み仮名をふって僕に意味を教えてくれた

When {there was difficult kanji}, mother {added yomigama to each one of them} and taught me [their] meanings.

- Context: an omake showing random panels each with a text starting with a syllable form the title of the manga (toukyou guuru トウキョウグール).

- ru

ル

(this syllable.) - très bien

Très bienトレッビアン

"Very good" in French. - calmato

Calmatoカルマート

"Calm down" in Italian. - kai

壊かい ッ!!

(probably something to do with destruction.) - jai

蛇意じゃい ッ!!

(probably something to do with wicked intentions.) - {rubi ga hitsuyou na} hito-tachi

ルビが必要な人達

People [for whom} {ruby text is necessary}.

- In Tokyo Ghoul, Tsukiyama Shuu 月山習 has the habit of inserting foreign words in text, while Shachi 鯱, "Orca," has the habit of shouting what may be some sort of name for martial arts techniques when fighting.

I stumbled upon this blog post while randomly googling about Japanese and I must stay, good job on keeping it both entertaining and informative. Enjoyed it a lot, nicely done ^_^

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteAlso, manga like Doraemon ignores furigana on elementary grade kanji a lot, and most manga ignores furigana on numerals altogether.

ReplyDeleteThat's true. I think older manga (around the 90's) have partial furigana instead of all-furigana, maybe because it wasn't the norm to go full furigana back then? I recall the first parts of Jojo having partial furigana, but later have full furigana.

Delete